The artist Marie Watt (b. 1967, Seattle, Washington) creates works honouring Native American culture and storytelling traditions. While she has become best known for her textile-based works, Watt has maintained a printmaking practice since the 1990s. A travelling retrospective on view at the Print Center New York (25 January-18 May 2024) titled Storywork: The Prints of Marie Watt, from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation focuses on this long standing part of her output, drawing parallels between the community-minded approach of all facets of her practice.

The show opened at the University Galleries at the University of San Diego in 2022 and travelled to the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 2023. In New York, it explores how Watt has told stories through varied mediums, including over 50 etchings, lithographs, and woodcuts dating from 1996 to the present, which Watt created with the support or inspiration of peers and mentors, and sculptures and textile works that she completed through communal sewing circle events.

Watt is an enrolled member of the Seneca Nation and has German-Scots ancestry. Her work is held in several major museum collections, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Print Center New York is hosting public pressure printing workshops every other Saturday through the duration of the exhibition and several other programmes.

Printmaking has been a less-exhibited but consistent part of your practice since the 1990s. What were some of your earliest experimentations, and what drew you to the medium?

My introduction to printmaking was at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon, as an undergraduate, and, as I think about it, it’s probably why I became an art major. I’m drawn to the intimacy of working on a plate, but also the community space that is the printmaking studio. Oftentimes, you’re working side-by-side with other artists, visiting while plates are being processed and learning from each other. The smell of oil-based inks, the sound of music and the hum of voices are part of the shop ambience. All these elements imprint on the creative process. I continued to explore printmaking in graduate school, and for my work-study job, I was a print shop monitor. These experiences solidified my early exploration of printmaking, but the ongoing experience of working with Master Printers—Julia D’Amario, Frank Janzen, Paul Mullowney, James Pettengill—has made printmaking a consistent part of my practice.

Some of your early works, like the engraving Untitled (Corn Husk Study—Alone) (1996) use corn husk motifs to speak about Seneca culture. Could you please talk about the symbolism behind the corn husk?

Corn is a vital, nutritional and spiritual source in Seneca and Haudenosaunee culture. Corn is one of the Three Sisters with Beans and Squash. The Three Sisters teach us that we are interconnected. Traditionally, these seeds are grown together in a mound of dirt that resembles a turtle’s back. Corn creates a stock for beans to climb. Beans create nitrogen-rich soil, and Squash’s broad leaf-covering protects the roots and soil moisture. When grown together, these plants thrive. They are a reminder of our relatedness. We need each other.

Prior to becoming a graduate student, I had been a student at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where there is a dense community of Indigenous people. Feeling isolated in New Haven, I started to reference corn and husks in my work. Using and evoking this material was a way to carry or create a sense of home in a new environment. In the print studio, I started to look closely at cornhusks. I began making soft ground prints using the husks. When dry, cornhusks are fragile, but when damp, this is a material that can be sculpted. It could also be braided into a cord that could save one’s life. If you hold a husk up to a light source, it is made up of intricate cellular structures that resemble lozenge shape forms relating to skin, architecture, and mapping.

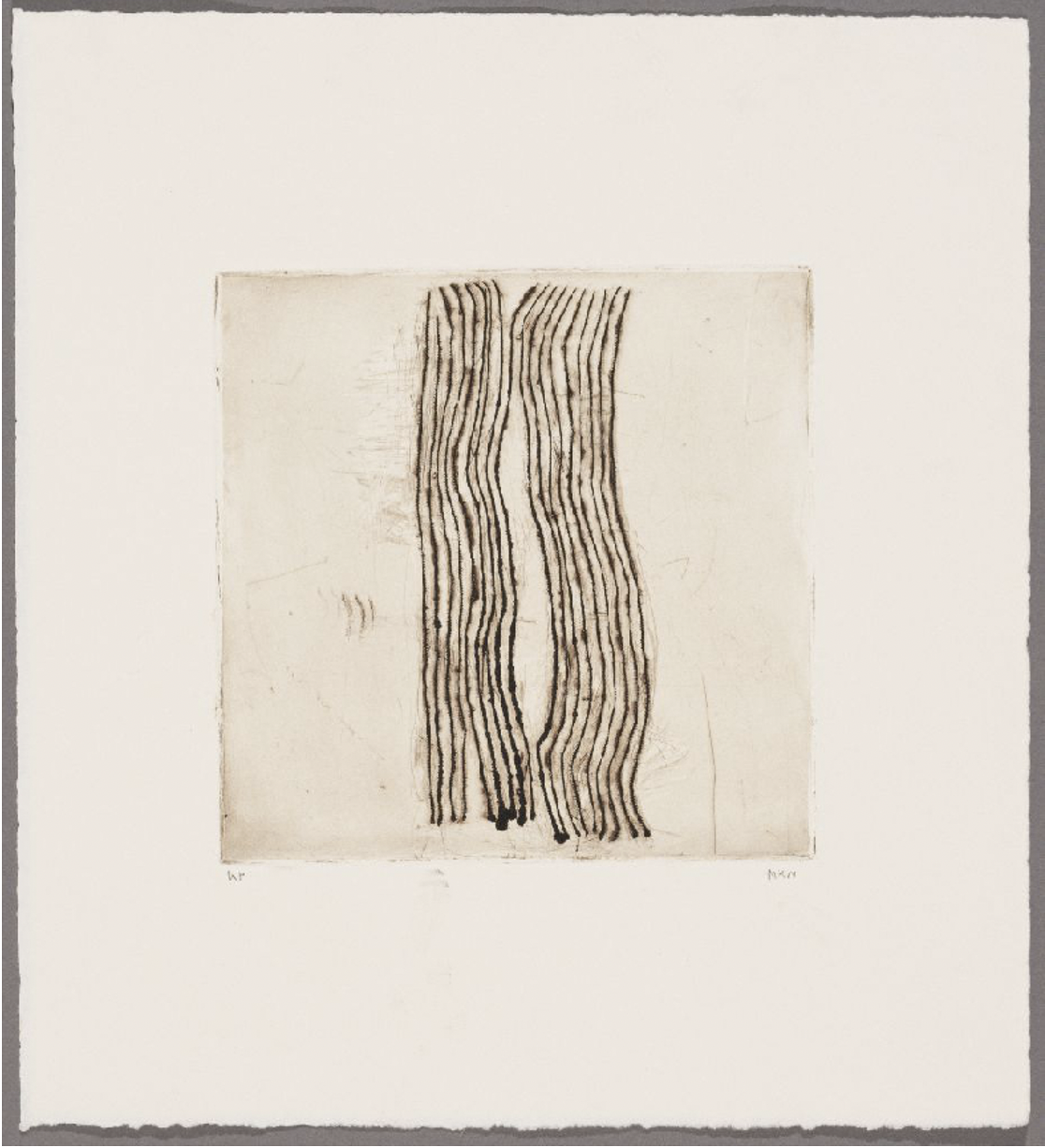

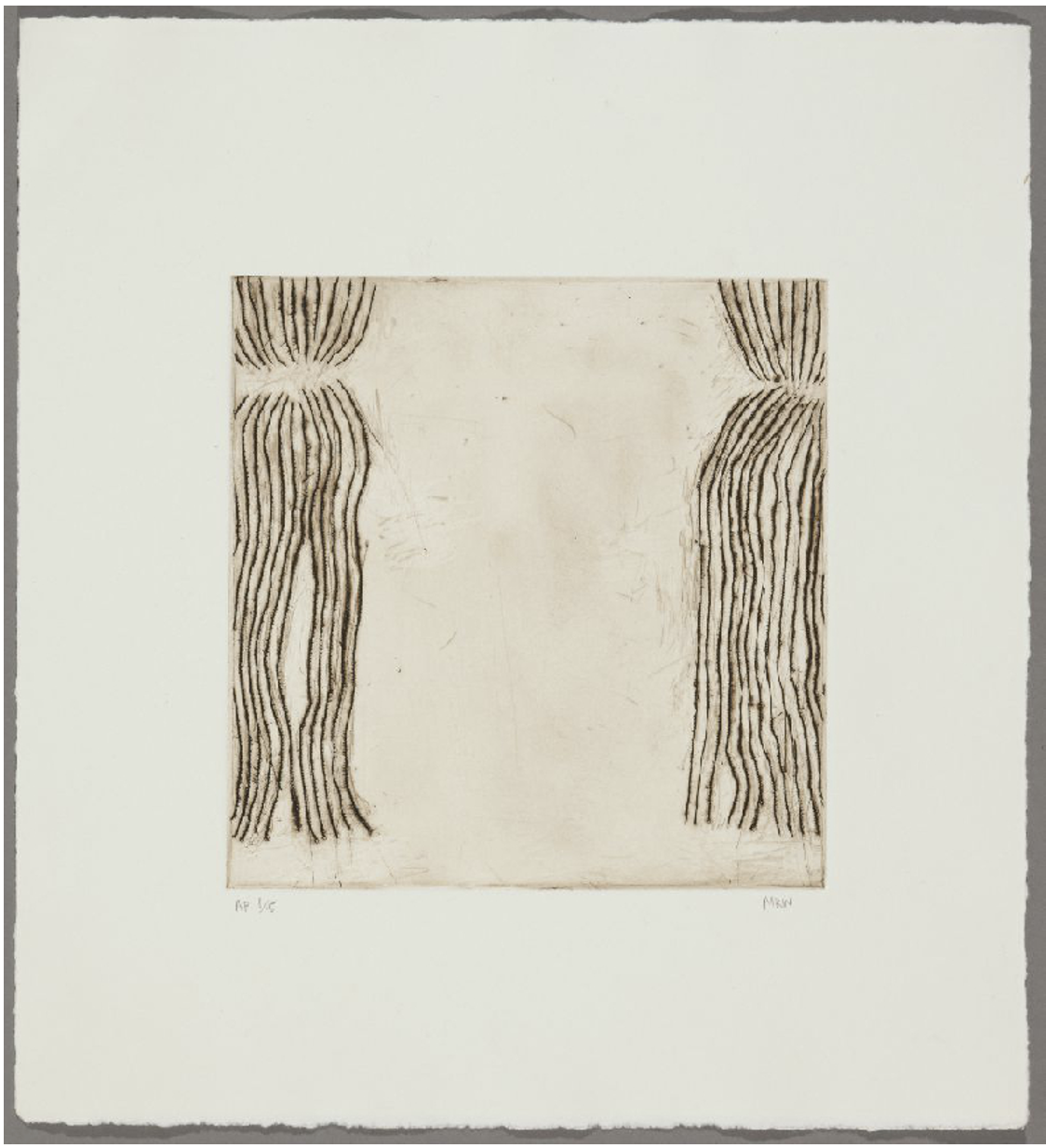

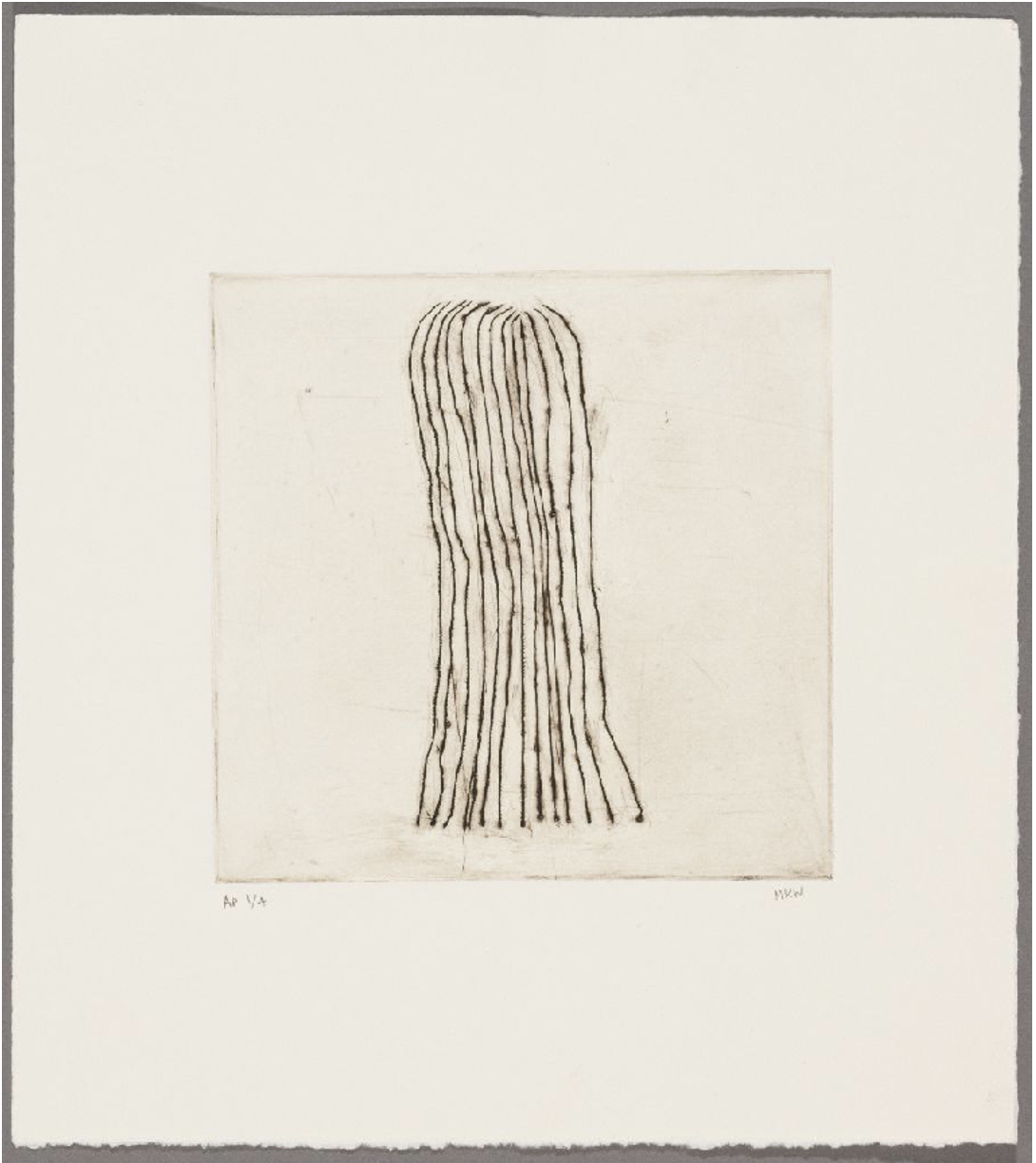

For the more minimal Untitled (Corn Husk Studies) (1996) I used an engraving tool—or more accurately, misused an engraving gouge—so that there are these razor-deep lines with occasional burrs on the copper plate; the resulting lines are dramatic.

You cite working with several Oregon-based institutions, like the Shadow Institute of the Arts, the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology and Mullowney Printing Company in Oregon, as well as the Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico, as foundational experiences. What did you learn over the years working with these organisations, and how have these experiences informed the collaborative approach of your printmaking and wider practice?

Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts, located on the Confederated Tribes of Umatilla Indians Reservation outside of Pendleton, Oregon, has been a major touchstone of my printmaking trek. Crow’s Shadow held a symposium called Conduit to the Mainstream in 2001. It included artists who, for me, were and remain giants in the art world, including—James Lavador (Crow’s Shadow co-founder), Kay Walkingstick, Rick Bartow, Truman Lowe, Edgar Heap-of-Birds and James Luna. Participants also included major innovative printmaking organisations, including Marge Devon, who at that time was the Director of Tamarind Institute. The symposium led to transformational relationships and opportunities, eventually including an invitation to print at Tamarind, a solo exhibition at the George Gustave Heye Museum, and a satellite of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American, curated by Truman Lowe. I believe to this day that all opportunities in my career can be traced back to Crow’s Shadow and the model for community and collaboration that it embodies.

The first opportunities I had to work with Master Printers included making lithographs with Frank Janzen at Crow’s Shadow in 2002, as well as with Julia D’Amario at Sitka Center for Art and Ecology that same year. What I didn’t anticipate from these first exchanges was the ongoing relationships with these printers and organisations that would come from this. The continuum of these relationships allows for a certain amount of comfort and familiarity. But also, when we re-unite, we can hit the ground running and push certain technical and visual experiments further.

While Mullowney Printing has long roots in the Bay Area, its arrival in Portland, Oregon, is relatively new. One of the things that I am enjoying about this Portland-based relationship is the allowance for projects to gestate over time. In some ways, it is an extension of my studio, which is to say that I feel very welcome there. I also love what the presence of Mullowney Printing Company does for the profile of Oregon’s art and artist community. They work with artists locally and internationally, which adds to the region’s rich art and culture scene.

You began organising sewing circles in the early 2000s, shifting your focus to textiles as a medium. The circle motif also reappears throughout your printworks, some that predate or coincide with the sewing circles. What does the circle represent?

For me, the circle is a flag, talisman and shield. One of the first things an infant experiences out of the womb is the glint of light in a loved one’s eye, and from there, circles abound… a nipple, a sun, a moon, a belly button, a ball, a wheel, etc. It should be no surprise that circles are one of the first shapes that children draw. My mom, Romayne Watt, who worked in Indian Education for 27 years, likes to say circles expand and contract to include everyone and that everyone’s voice is equal in a circle. I am also interested in how a piece like Threshold (2006) inserts itself into a conversation with the work of Jasper Johns and attempts to reclaim concentric circles from a certain retailer.

You solicited help from the community to complete some of the more large-scale textile pieces, like Threshold (2006). You mention: “Watching my friends with their heads down, hands busy, stories flowing, I learned once again the importance of community.” What are your earliest memories of organising sewing circles, and what ideas or revelations did those experiences spark?

I would compare my earliest sewing circles to a barn raising in the sense that many hands make light work, and there is a spirit of reciprocity that accompanies this invitation. I quickly realised that the sewing circles weren’t a means to an end but a means for coming together, making community and connecting with neighbours. When eyes are diverted and hands are busy, stories flow. Now, I would like to say that I set the table, and what happens at the table is created by everyone. We live in a time where our technology and our devices interfere with our ability to get to know our neighbours. The sewing circles and other collaborative projects, like the printing circles I’m hosting at Print Center New York, create an opportunity to make things in the community. Individual expressions become part of a larger whole, but the conversations and storytelling imprint on these objects, too. This model of making—teaching, learning and storytelling—is not just Indigenous in origin. It can be traced back to all early communities. It’s part of our DNA. In this situation, multigenerational and cross-disciplinary voices share the same table. I acknowledge these exchanges by sharing a small limited edition print with participants.

The exhibition opened as a larger retrospective in 2022. How did you determine what you would include in Storywork? What stories did you want to tell?

I have to admit that when I first received the invitation to have a retrospective of my print work, I hadn’t really considered it to be a significant part of my studio practice. It was fun discovering the degree to which printmaking has been a consistent thread. In this larger retrospective, I am drawn to seeing the large totem-like reclaimed wood sculpture, Skywalker/Skyscraper (Sapling Meets Flint) (2021), knowing that it is my ongoing relationship with wood that prompted me to work on woodcuts at Crow’s Shadow as early as 2005.

With collaboration as a central part of my practice, I also wanted to revisit the idea of hosting a printing circle as part of the exhibition programming. The first Printing Circle was held in 2018 at the invitation of Petra Sairanen at Portland Community College’s Rock Creek Campus. Participants drew pre-curated text from a bag and were invited to interpret their words on plates. In this case, the printmaking “plate” is a piece of cardstock, and participants created a relief surface by glueing cut paper to the plate or by stitching directly into the plate.

The cool thing about this project is that within an hour, a person can make a plate and print it by using tissue-thin paper and then inking a brayer that captures the relief of the paper or thread below the surface. Participants walk away with prints and are also invited to contribute their plates so that the subsequent prints become part of a larger global project with individual and collective voices. Words, my words, fail to capture the buzz, energy, concentration and smiles in the room. But the resulting prints hint at it and, in a way, are a touchstone for those who were present.

Written by Gabriella Angeleti