Mark Leckey has been feeling, as he puts it, left in the dust lately. During lockdown he watched video clips on TikTok, where fast-moving edits and snippets of amateur footage are layered with everything from intimate dialogue to the latest club tracks. Moving images are pulled rapidly from a range of sources and spliced together, often without context. “Technically, creatively, I feel superseded by it,” he says emphatically. “Genuinely!”

It’s not difficult to see the connection between the online video culture of recent years and Leckey’s own collage-based approach to his video works. Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, the 15-minute film that first gained him recognition as an artist in 1999, knits together grainy clips of dancers from a wide range of time periods and locations.

The UK’s club culture is hazily evoked, alongside a palpable sense of both proximity and distance. The careful editing of the archival footage in Fiorucci, set to the intense, relentless beat of a classic acid house soundtrack, destabilises the imagery and lends it an otherworldly, almost wistful quality. “There was something in the grain of that transcoded VHS, because the quality was so poor, that gave it this slightly ghostly image that was very powerful in itself,” he says.

It has developed a cult following over the last decade, with the freely available YouTube link (uploaded by Leckey himself) whisperingly shared between art school students and club kids as if it were the latest underground release. The film’s audio was sampled by Jamie XX in All Under One Roof Raving in 2014, and Leckey starred in fashion house Bottega Veneta’s campaign earlier this year.

It is telling that these new legions of Leckey fans are internet savvy. Many see their own fractured experience of the digital world reflected in the cut-up editing style that he introduced to the art world in the 1990s, in part influenced by the music videos of the time. “I really wanted to make music videos but it was harder for me to get into it,” Leckey admits. “I had no connections and it was an oversubscribed field that I couldn’t get near.”

Leckey’s identity as an English kid from a northern, working-class background shapes his work. Growing up in Ellesmere Port, just south of Liverpool, he never imagined that he would end up as an artist. The post-industrial landscape that formed the backdrop to his early years is a recurring motif in his work. Notably, many of the clubs shown in Fiorucci were located outside of London and Manchester, in towns like Wigan and Preston.

“There is a need to join together and to create a space where art and music can cross-pollinate”

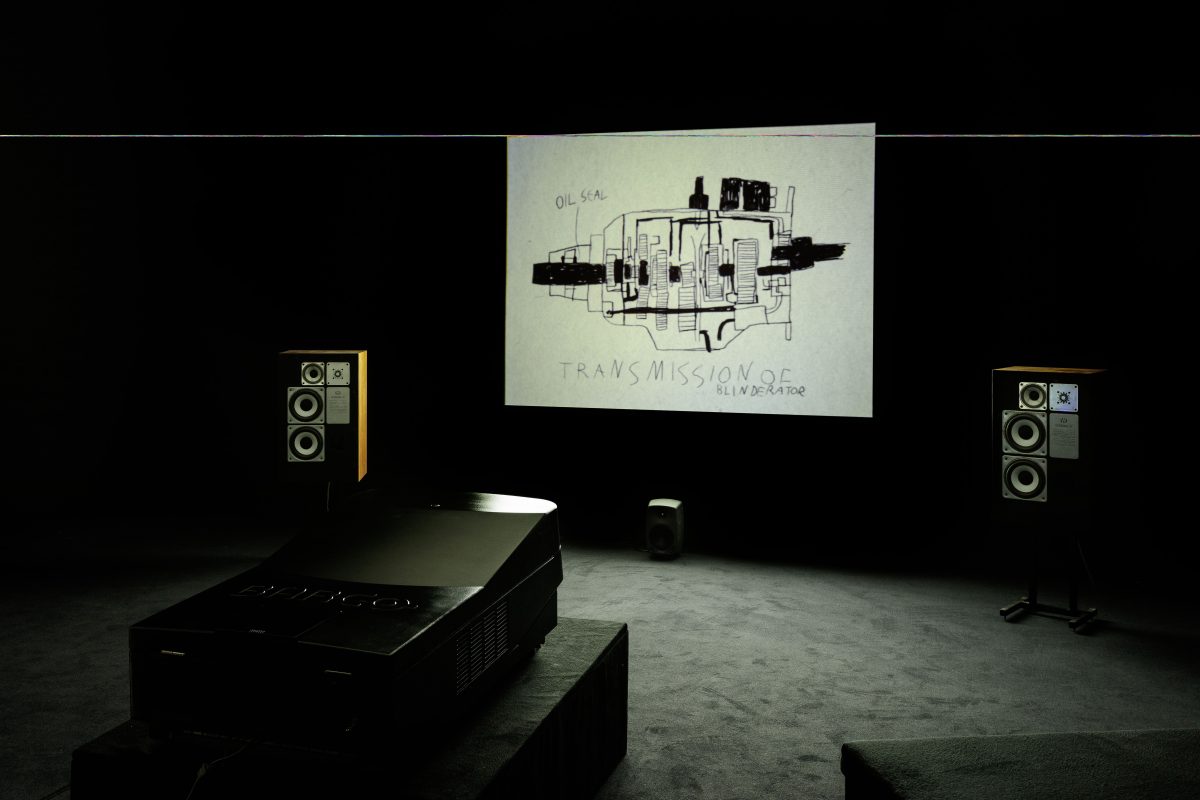

“I grew up with an idea of a particular English landscape,” he recalls. “It was the north-west in the early 1980s, which was very derelict.” A life-size replica of a motorway bridge that he encountered as a child in Merseyside made an appearance in O’ Magic Power of Bleakness, the solo show that he mounted at Tate Britain in 2019. An accompanying audio play conjured the listlessness of long days spent as a teenager in a small British town with nowhere to go, watching traffic slip endlessly by.

The peculiarities of Englishness intrigue Leckey, who often draws upon folklore and mysticism within the concrete expanse of urban spaces rather than rural ones. Instead of turning his attention to “spooky moors”, he finds that “wasted industrial plants have their own haunted quality.” Magical realism animates all his work, whether it’s the view of a suburban motorway or the joyful communion of the dancefloor. “It’s a way of being able to talk about my background without resorting to the clichéd, social-realist observations,” he says. “It’s a way of talking about class.”

“It has become transparently more and more difficult for working-class people to get to art school”

Following Britain’s departure from the EU, how does Leckey view his country now? After years of making work about the underside of this nation, what does England mean to him today? He sighs, laughing at what is ultimately an impossible question. “England has become very regionalised: you move from one England to another,” he begins. “There’s a line by William Gibson: ‘The future is here already, but it’s just not very evenly distributed’. I don’t know how you speak inclusively about England because the point is it’s not inclusive, and that seems to be the conflict.”

Access and inclusivity in the art world, especially for those from less privileged backgrounds, is just as unevenly distributed. Leckey points out that his path to becoming an artist was relatively straightforward. “I went to art school and got a full grant and housing benefits,” he says. “But it’s changed a lot since then. Just teaching, I see fewer and fewer working-class people on the course. It has become transparently more and more difficult for people from those backgrounds to get to art school.”

What can redress the balance of access in the arts? It’s a throwaway question with no real expectation of a definitive answer, but Leckey surprises. After an extended pause, he reveals with audible excitement that he has already dreamed up a project. “My idea is to set up a school, or at least a summer school,” he enthuses. “I want this school to teach music and video, and a broad spectrum within that. It could be anything from TikTok to YouTube documentaries or artworks, with a focus on digital production.”

“It’s a way of talking about my background without resorting to the clichéd, social-realist observations. It’s a way of talking about class”

“I think there’s a space opening up between art and music, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic,” he continues. “There is a need to join together and to create a space where these things can cross-pollinate.” Leckey already presents a show on NTS Radio and releases his own music, most recently In This Lingering Twilight Sparkle in 2021, inspired by his interest in folklore and fantasy, with all profits donated to mentoring charity Arts Emergency, who help young people to enter the creative industry.

Music and popular culture are touchstones within Leckey’s work, from acid house anthems to the titular Italian fashion brand Fiorucci referenced in Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore. “It was an attempt to celebrate or legitimate a subculture that wasn’t taken seriously at the time,” he says. In 2016’s Dream English Kid 1964-1999AD, he made use of found footage to tell the story of his life from birth to the age of 35 through the cultural artefacts that surrounded him, from television adverts to film clips, which he calls “found memories”.

Again and again, Leckey finds himself looking to the past, back to his pre-adolescent years and his time as a teenage small-town rebel. Memories can attach themselves vividly to objects, brands and clothing, tying a highly personal notion of ourselves and others to a mass-produced item or a snippet of television. “I think nostalgia is a condition,” he says. “And I think it’s a byproduct of late capitalism. It unconsciously produces this nostalgic effect.”

The internet fascinates him as a space where high and low culture collide, and where people come together to share ideas that go beyond the mainstream. “The internet produces subcultures as much as the music industry of the 20th-century produced its subcultures,” he says. “I just think they look different.” He is hopeful about what it means “to live in this new paradigm, this new digital realm”, which represents “a cultural landscape that is still emerging.”

Leckey continues to look to the margins to tell the story not only of his own past but of entire communities who might otherwise fall between the cracks. He lends these moments of togetherness a melancholic gravity that is as unnerving as it is chest-swellingly emotional. It unfurls across Leckey’s work, revealing magic in the ever-changing tides of human connection.

Louise Benson is Elephant’s deputy editor

All images courtesy the artist and Cabinet, London