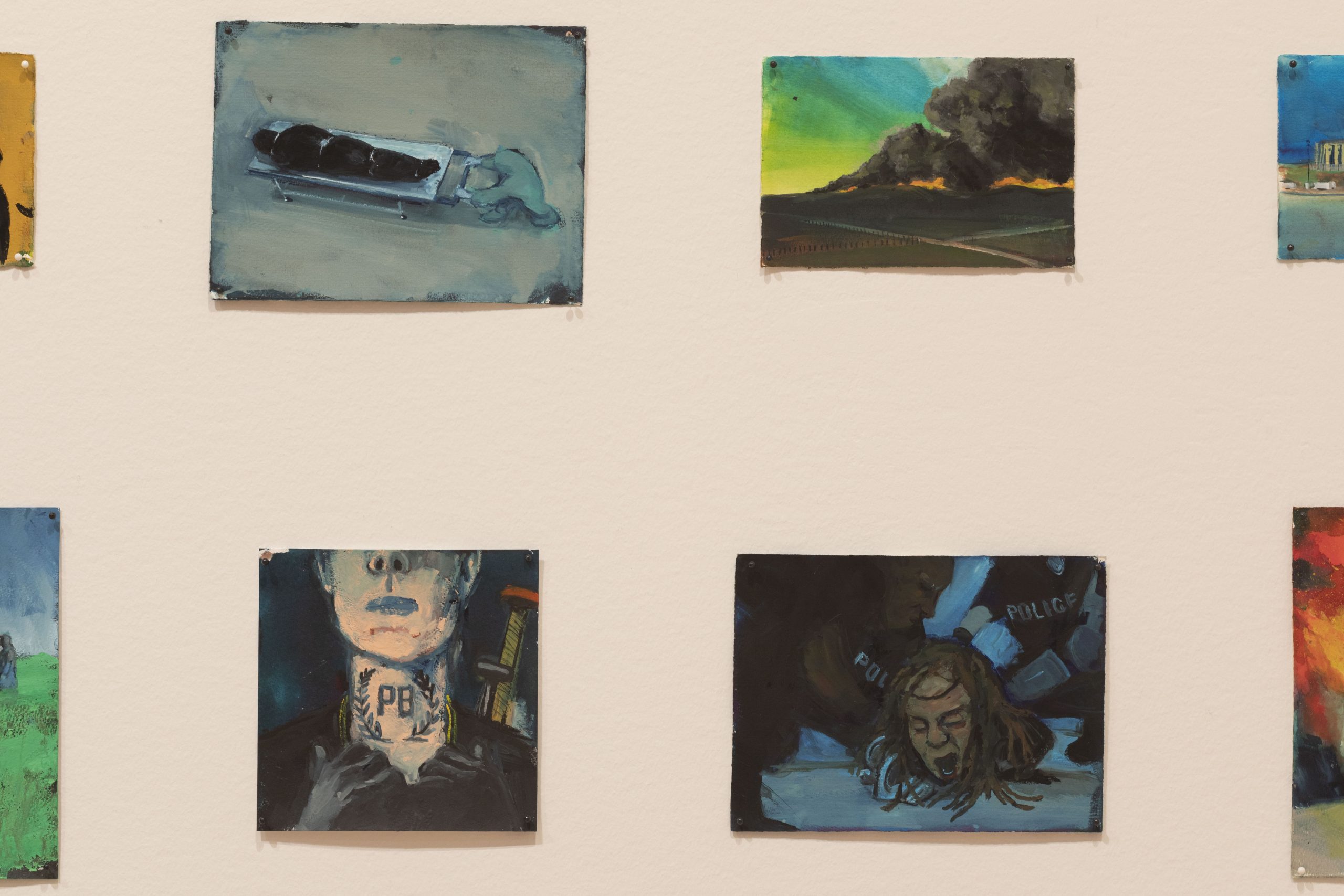

When James Gouldthorpe started posting his lockdown paintings on Instagram last March, he didn’t imagine that in a year’s time they would be hanging in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The gallery, where Gouldthorpe has worked for 30 years (first in the installation team, now as a conservation technician

), has strict policies around showing staff works, but his sketchy, understated paintings documenting the pandemic caught the eye of curator Corey Keller. She asked him to show at Close to Home: Creativity in Crisis, a showcase of pandemic art by Bay Area artists running now until the beginning of September.

Gouldthorpe’s series, Covid Artefacts, is organised by month, each section comprising between 20 and 30 paintings that depict important moments from the pandemic. The 29 studies for April 2020 include a bottle of hand sanitiser, jackals roaming wide streets, and a distant shot of gravediggers in eerie white overalls. There is also a lighter touch: scroll through to find a six-pack of Corona Extra beer, a laptop loaded with the Pornhub website, and a rendering of Joe Exotic from the hit documentary Tiger King. “At some point I realised that it was going to be a daily journal and it wasn’t going to end after two weeks,” Gouldthorpe explains. “It wasn’t really an idea: it was just a reaction.”

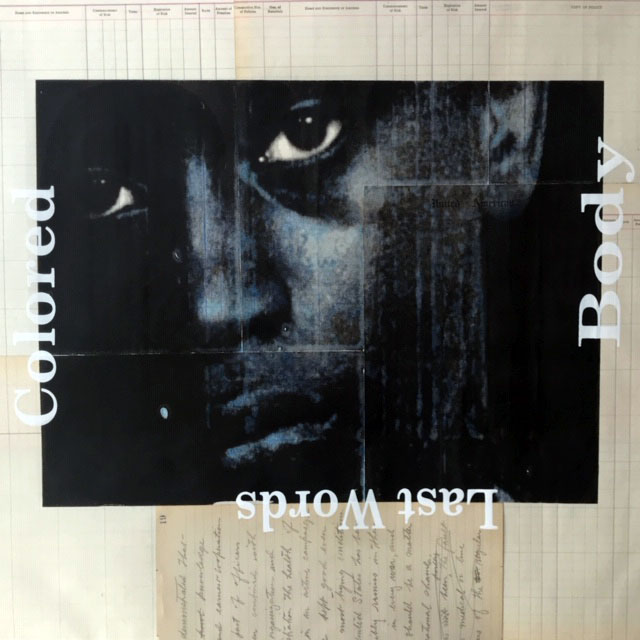

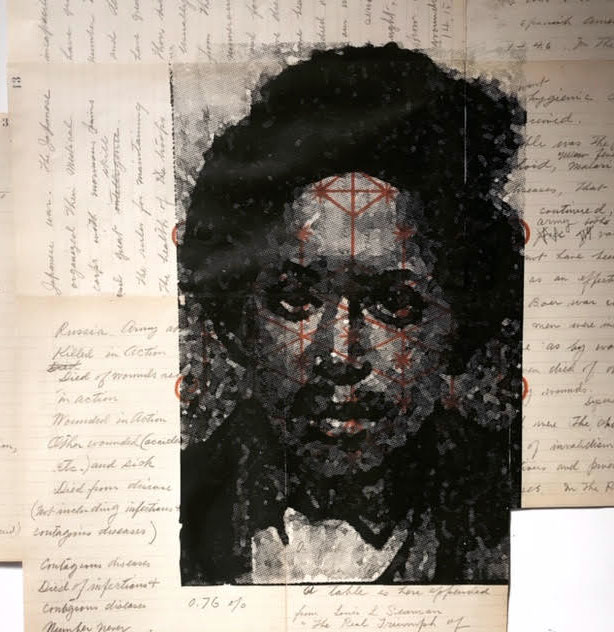

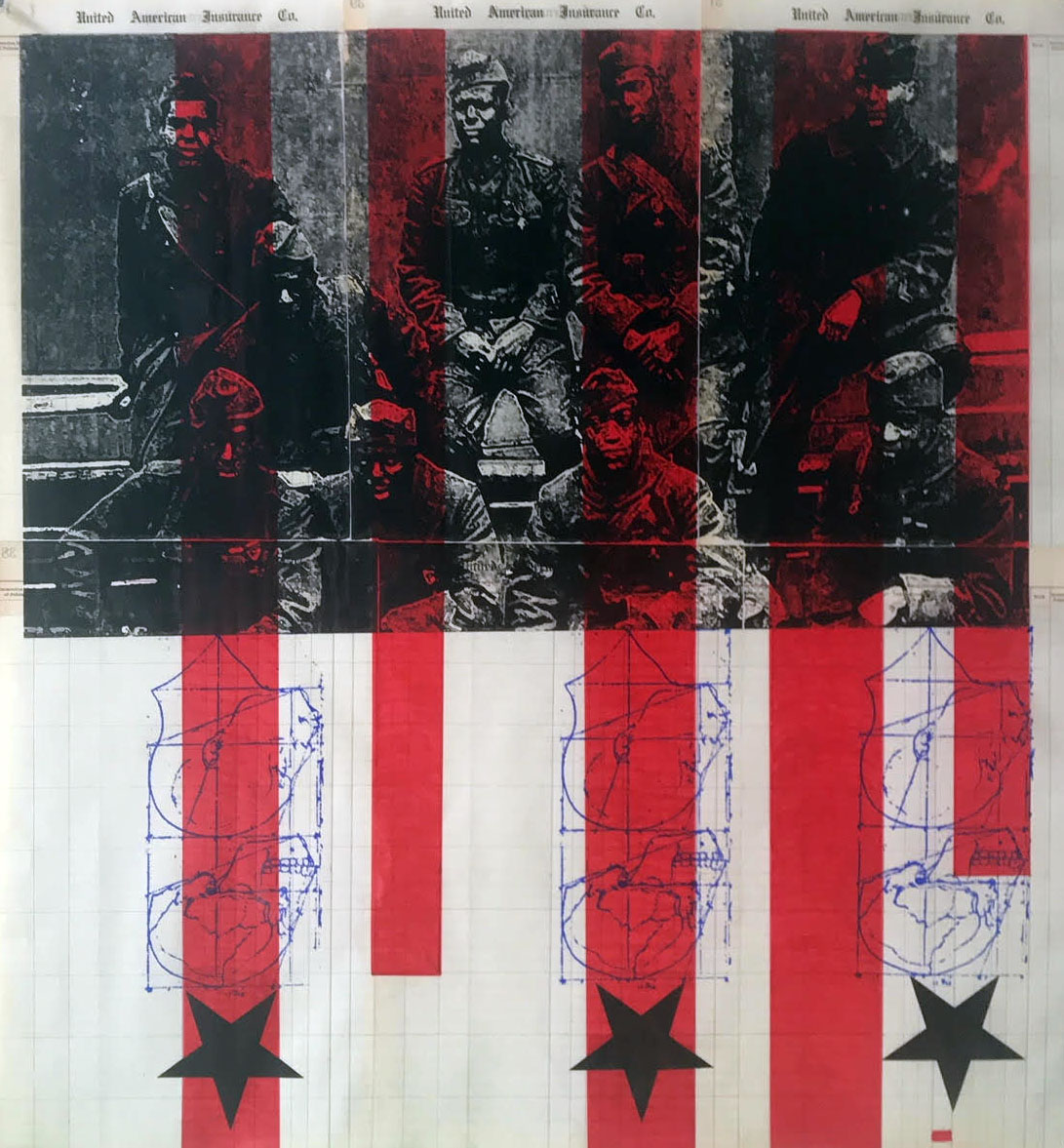

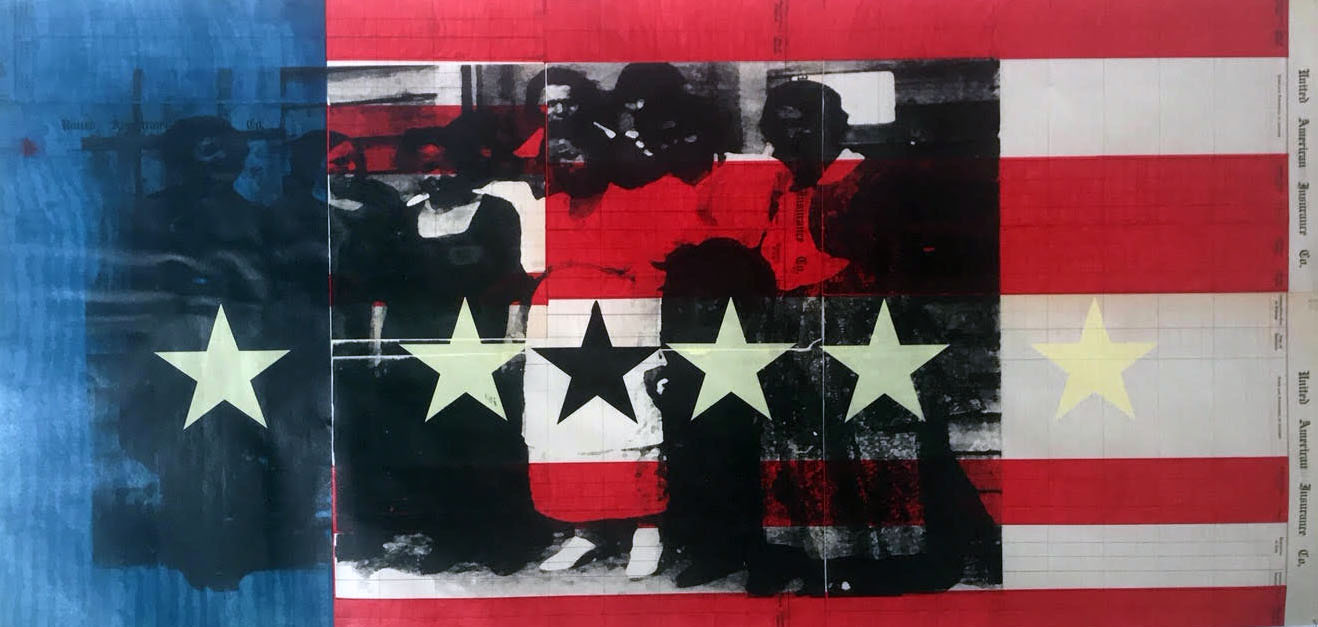

Reaction seems an appropriate word to describe the full range of works in Close to Home. Opposite Gouldthorpe’s canvases hangs a grid of Klea McKenna’s pastel photogram; across the hall are works by Carolyn Drake, Andres Gonzalez, Tucker Nichols, and Woody De Othello. Rodney Ewing’s mixed media works stand out for their use of text and American iconography: One Has to Be (George Junius Stinney, Jr) tells the tale of Stinney’s wrongful execution in 1944 aged just 14, an episode with painful resonances in 2020. Others bear the American flag, but look beyond its ceremonial function to a darker past.

The exhibition’s premise will doubtless be repeated globally in the coming months. By showcasing local series created during the pandemic, galleries can reveal the nuances of artistic process which distinguish the works from their creators’ back catalogues while also encouraging identification with shared subject matter.

To define the past year as a creative timeframe is inevitably to invite its layered traumas into the work. All artists mention not only the pandemic but also the summer of racial protests and a fraught election cycle as compounding factors during months of uncertainty and risk. For Californians, 2020’s record-breaking wildfires also brought significant distress to the population. With travel restrictions limiting the potential audience mostly to state residents, Close to Home claims to “emphasise our shared experience in this collective crisis”, but how do the artists reflect on making work under these constraints? And what might be the legacy of these disrupted processes?

“I like the idea of slowness, of these undifferentiated days being compressed into an image”

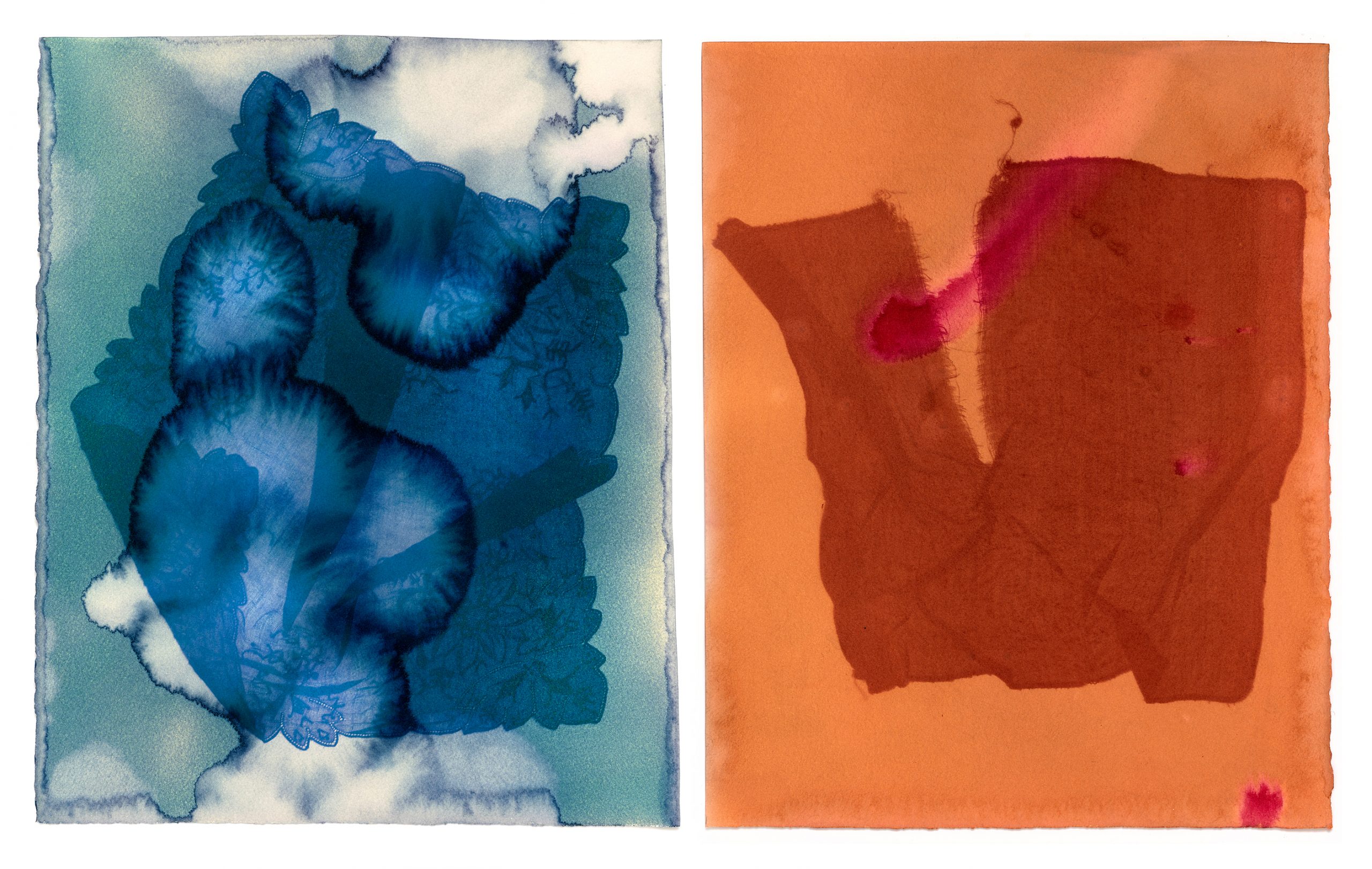

For Klea McKenna, having to shift her practice to the home was the most significant consequence of the lockdowns, especially with two young children. McKenna’s series No Feeling is Final is a form of camera-less photography: she recalibrates the fundamental processes of the medium using light-sensitive watercolour ink and sunlight. Without studio equipment, McKenna combined inks that fade at different rates into dark blends. She then soaked handkerchiefs in the solution and laid them on photo paper so the cloths acted as negatives. Left to dry on her rooftop, the California sunlight (and sometimes rain, even as she rushed to bring them inside) fade and blot the paper. When the handkerchiefs were removed, the lace impressions were left with an abstract, interrupted effect.

The technique was born of necessity. Away from her studio and with public schools in California closed since 13 March 2020, the tactile process allowed McKenna to involve her two idle children, stretching the project to fit the seemingly endless time available. “It’s a way for me to maintain my sanity, and carves out a small space in each day in which to perceive, process and communicate what’s happening via a different mode,” she says. The handkerchiefs have taken on a symbolic meaning: intimately tied to the body, they similarly evoke health, propriety and compassion. Dying them black with her six-year-old daughter became a way to introduce a necessary darkness (perhaps even a morbidity) into the work without sacrificing its tenderness.

Like Gouldthorpe’s plotted history of the pandemic, McKenna began writing a Pandemic Process Blog on her website to guide viewers through her textile process. In one entry, she describes how she adapted her rooftop fire escape with plexiglass to make it a suitable drying surface for her compositions; in another, her prose hastens into a collective voice for Californian pandemic citizenry. “We were waiting: waiting for a vaccine, or for herd immunity, waiting for schools to reopen, for covid test results, for the fires to be contained, for the air quality to improve, for the evacuation warnings to be lifted, for the smoke to move through, for the heat wave to pass, for it to rain, for financial relief checks, for more information, for the government to do something to help…”

“At some point I realised that it wasn’t going to end after two weeks…”

This tendency for creativity to become diaristic is common among the Close to Home artists. Deadlines evaporated with showcases and exhibitions cancelled, leaving an empty calendar into which single-study, iterative works have acted as placeholders. “I like the idea of slowness,” McKenna says, “of these undifferentiated days being compressed into an image.” Gouldthorpe’s paintings are themselves calendar-like, each month distilled into snapshots resembling a retrospective time lapse.

McKenna’s exposures take longer to complete, though their frequency allowed her to presell works while they were still developing in her home, creating a small-scale supply chain. Here making art becomes an inevitable process, rather than one activity chosen from many. There are now more than 180 works in McKenna’s series, 40 of which hang in buyers’ homes across the US; for Gouldthorpe, the total figure exceeds 400.

Ewing, who has lived in the Bay Area for 30 years, was fortunate to find that his studio remained open during the pandemic, and yet he also reports a similar shift in his relationship to his practice. “Making work became a ritual,” he explains: “I needed something to keep me occupied and present, so with this new body of work, I started creating a new piece every day and a half.” His series Broken Shadows is named after jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman’s 1982 album, and refers back to Ewing’s photographic training process “where you’re using negatives to creative positives,” he explains.

- Left: Rodney Ewing, One has to be (George Stinney Jr.), 2020. Right: Rodney Ewing, H. Box Brown as Loa, 2020. Courtesy the artist

Before the pandemic, Ewing knew that he wanted to use his extensive catalogue of silk screens (“I never wash or throw them away”) to start what he describes as “visual conversations about race, about identity, about memory.” But the cathartic potential of making art during lockdown came into collision with the Black Lives Matter protests, and the renewed relevance of his work to a city often complacent about its progressive credentials. In the wake of the death of George Floyd, a friend asked Ewing to produce an artwork in the Pacific Heights neighbourhood of San Francisco, “where there’s not a large range of diversity,” Ewing says.

“Her [the friend’s] emphasis was that after walks in other parts of the city, she would come back to her neighbourhood and it was almost like what happened to George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery didn’t happen.” Ewing recounts. “It was like Black Lives Matter didn’t make its way into her part of town, so she wanted to do something that reflected her concerns.” The resulting mural, Correspondence, combined the images of the three victims with text from Saul Williams’ poem Release serving as a eulogy across mediums.

“I needed to do something to respond to what I was seeing occur in my community,” Ewing says. Swapping hours in the studio for walks around the city, he was struck by the conversations that the mural prompted. “Others needed to see that as they were coming down that corridor,” he continues. “People needed to have that conversation and I needed to engage with them, even if I didn’t know them.”

Pandemic restlessness has recast artists as social historians: whether turned inwards or outwards, all three describe a journalistic compulsion which came to govern their works. These were, it seems, events and feelings that became unavoidable for art. Gouldthorpe recounts walking around Close to Home, eavesdropping on visitor conversations and wondering what the art’s legacy might be. All three hope that their series will have an afterlife, whether commemorative, commercial, archival or international. The lasting message is to expand the work’s associations beyond just its pandemic’s timeframe: “This is not just the work we did during Covid,” Ewing reflects, “this is the work we used to keep ourselves present, and in some kind of dialogue with the art community, but not ignoring the world around us.”