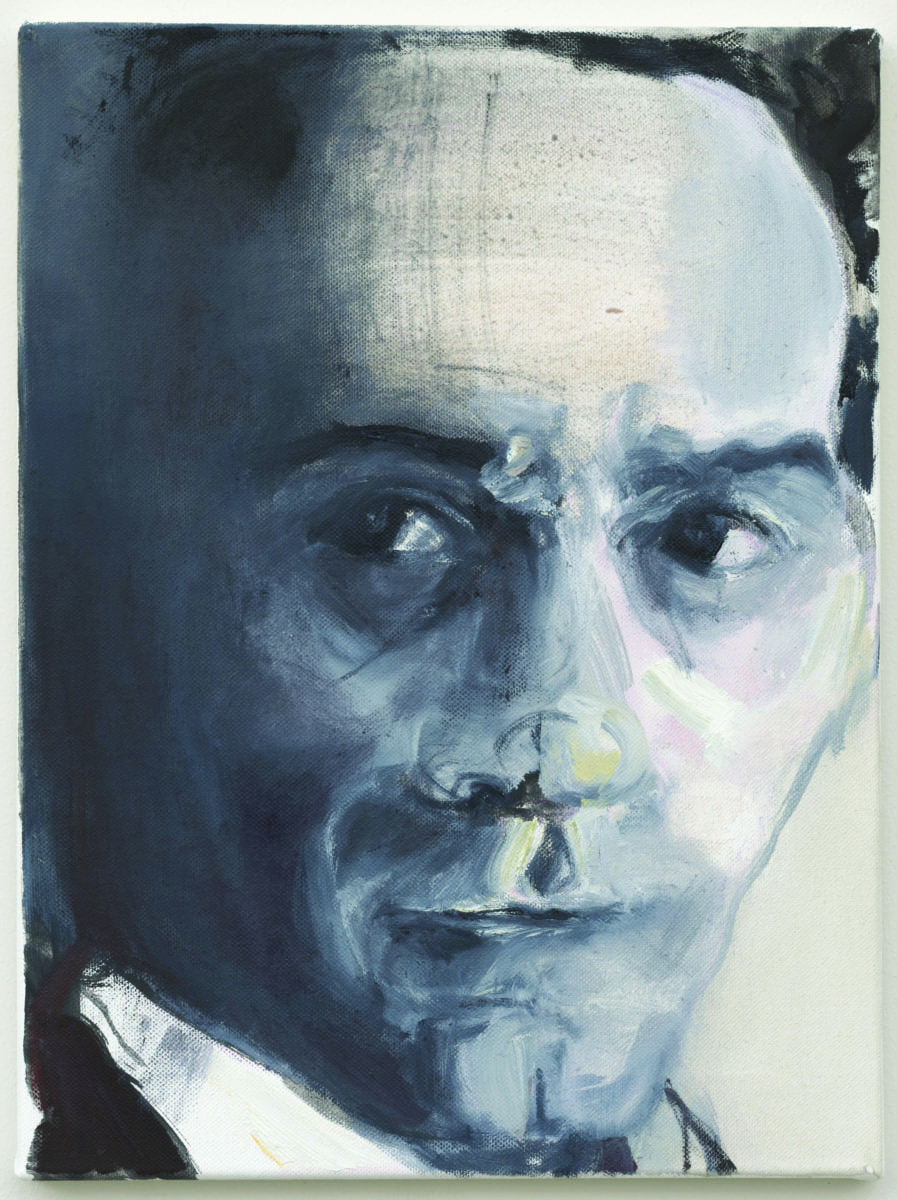

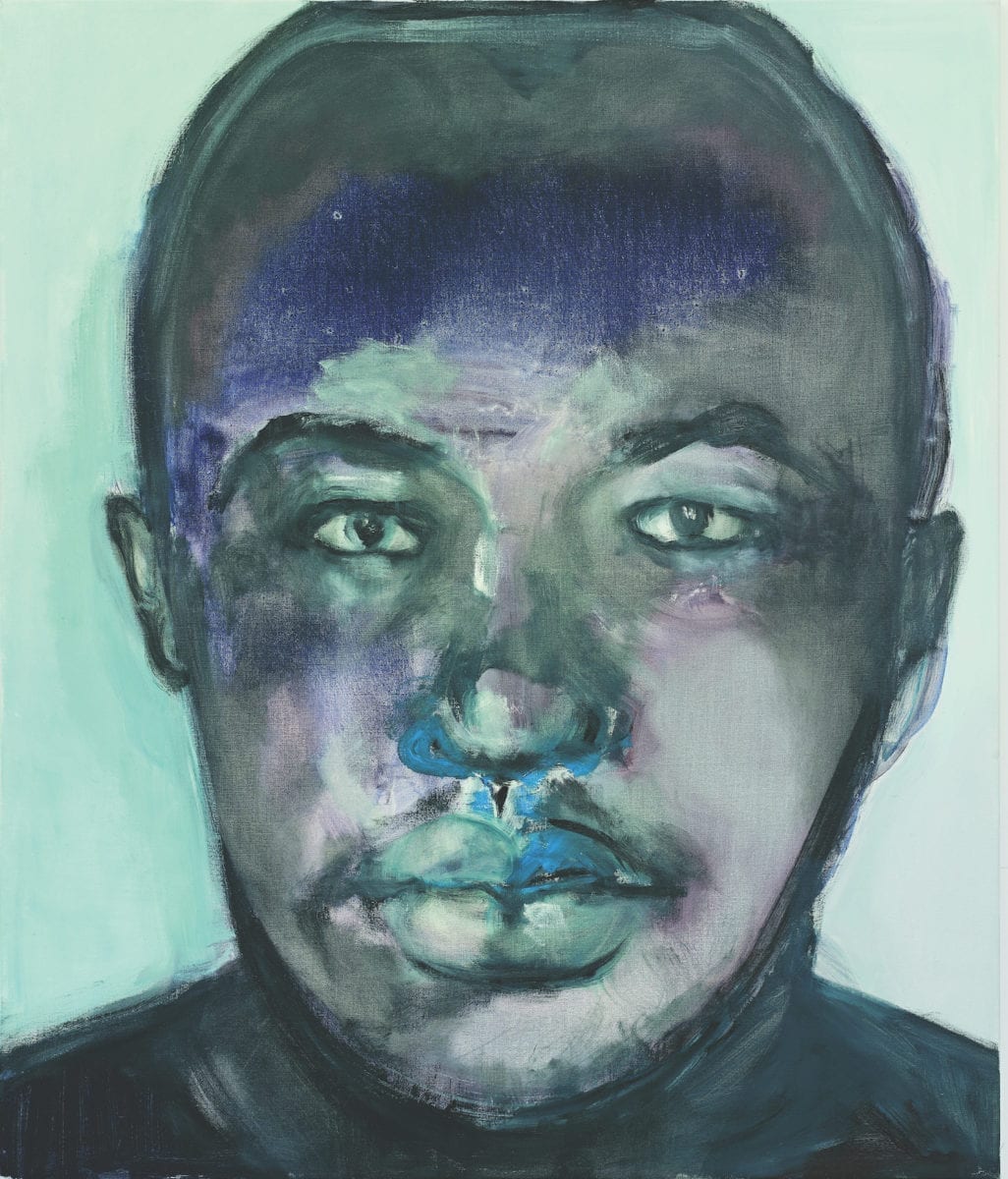

While planning a retrospective of the work of Marlene Dumas, The Image As Burden, one painting sharply divided staff at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum: those who loved it, and those who didn’t want it in the building. The Neighbour—Dumas’s gentle portrayal of the murderer referred to in the Dutch press as Mohammed B, who killed film director Theo van Gogh in broad daylight in Amsterdam—was tender and intentionally distanced from the aggressive clippings and news bulletin features she’d worked from to draw the piece. In the end, despite the differences of opinion, the painting had to go in, says Leontine Coelewij, head curator of the show, who cites The Neighbour as the most conclusive example of Dumas’s power as a political artist: “She made him seem so human and so alive and… normal. The murder was covered widely here in Amsterdam and Marlene portrayed this guy who was described as a beast in the media with these very soft features to make him seem more sweet. She’s asking us to look at how we create an image of somebody in our mind. She takes a newspaper clipping and through recreating it shows that images must be reinterpreted. She’s been doing this since the 1970s, researching the meaning of the image.” Coelewij’s deep knowledge of the artist’s practice informs The Image As Burden, which spotlights the vast image archive Dumas has maintained since the beginning of her career. “Marlene and I have been friends for over twenty-five years. I grew up with her work and, seeing her around Amsterdam, we became close. I was a student in the 1980s and I saw her exhibitions and really followed her style. This show is a very personal project for Marlene and for myself.”

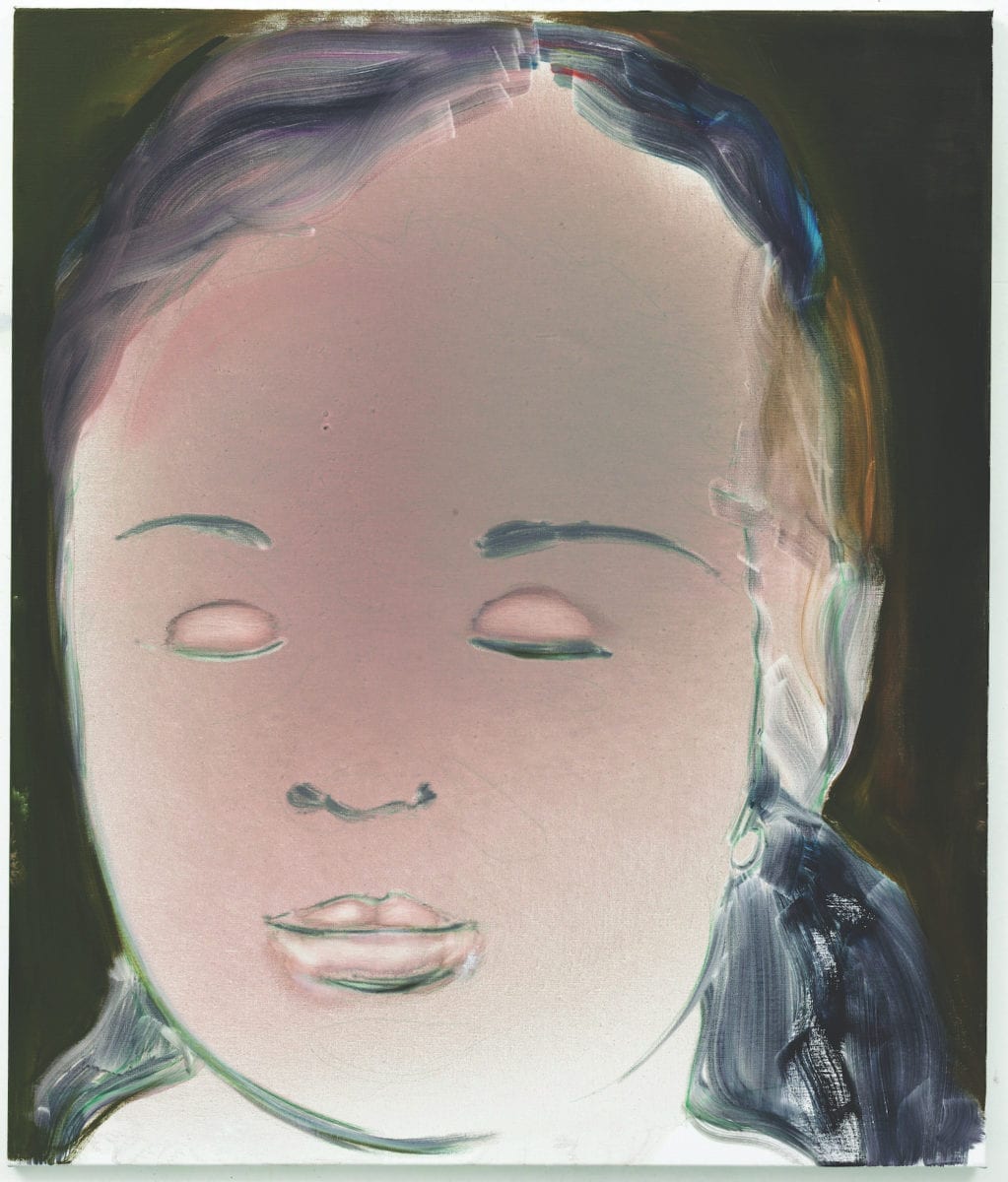

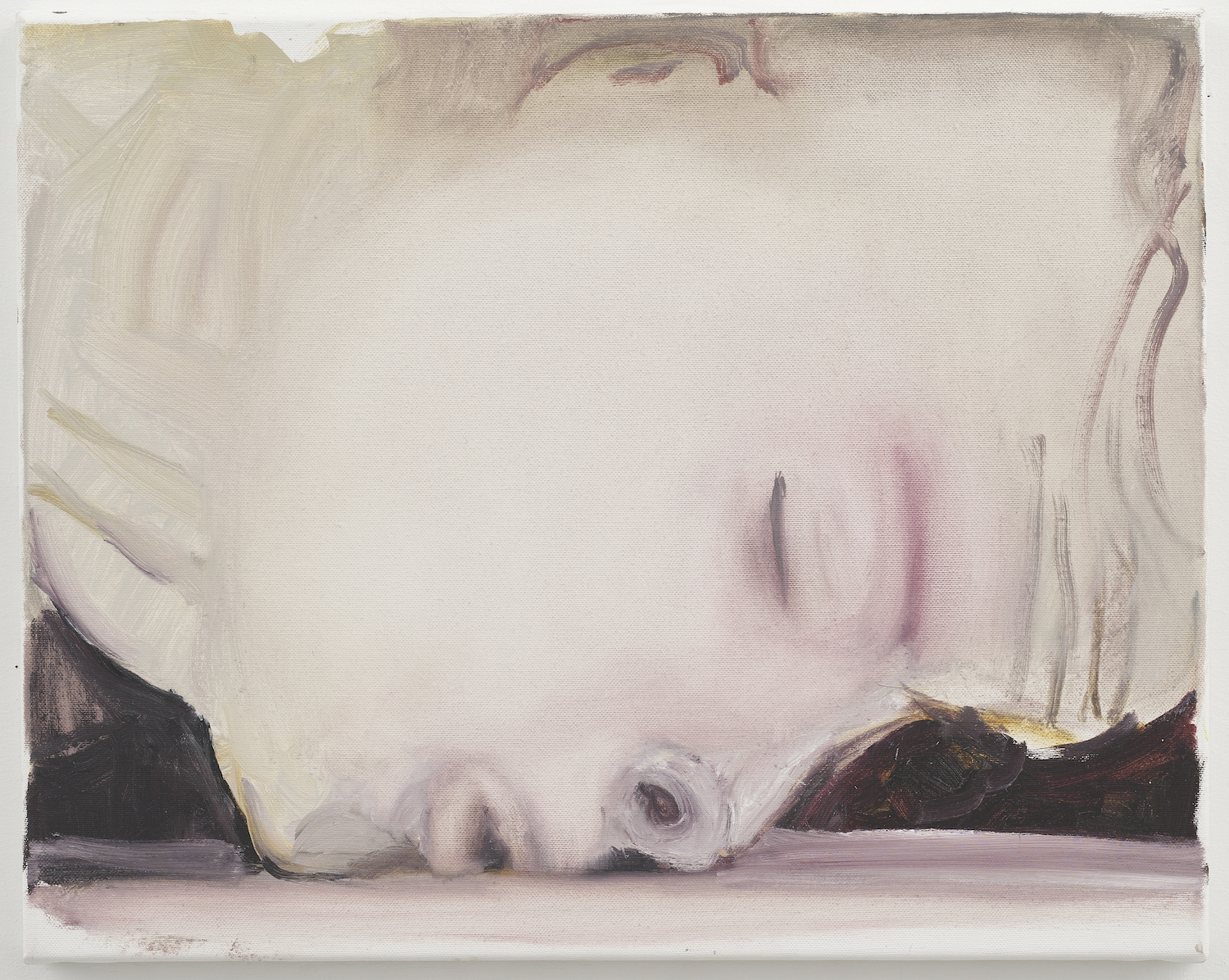

- Left: Helena's Dream, 2008. Right: Pasolini, 2012

Dumas’s collection of news clippings, magazine articles, photographs and other items has always informed her painting. She also keeps a personal archive of pictures she has drawn herself. She’s used both for reference throughout her career and The Image As Burden examines the impact of these collections on her painted output. The title of the show was suggested by Dumas and name checks a painting from the 1990s. It’s a heavy title—but not that heavy, insists Coelewij. “It’s not as bad as her last New York show, Measuring Your Own Grave,” she points out.

Her 2013 painting The Widow looks at the death of Patrice Lumumba, the Congo’s first democratically elected Prime Minister who was deposed in September 1960 and killed by firing squad a few months later. The reference for this work was a clipping from a 1961 newspaper. In this painting all aspects of her work align—the female body as a sign of grief and sadness, post-colonialism and ownership. Through 2009’s The Wall, Dumas examines the Israel-Palestine conflict in war reportage style, starkly documenting the daily toil of those living within the conflict. It’s a work that perfectly exemplifies Dumas’s process, and her own frustrations within it. Using a newspaper clipping as her reference, she transforms the photographic into something abstract.

“She’s asking us to look at how we create an image of somebody in our mind”

Portraits of contemporary characters from strippers to terrorists address the public and private construction of a personality, while the translucent blues and yellows mixed with the subtle smile in a portrait of Bin Laden encourage the viewer to reinterpret an international image of hate. “She deals with a lot of heavy issues and she reflects on what it is to be a political painter,” says Coelewij. “She looks at the divide between Israel and Palestine and the global issues of South Africa. The political pieces in the show aren’t one-offs, she’s committed to weighty issues.”

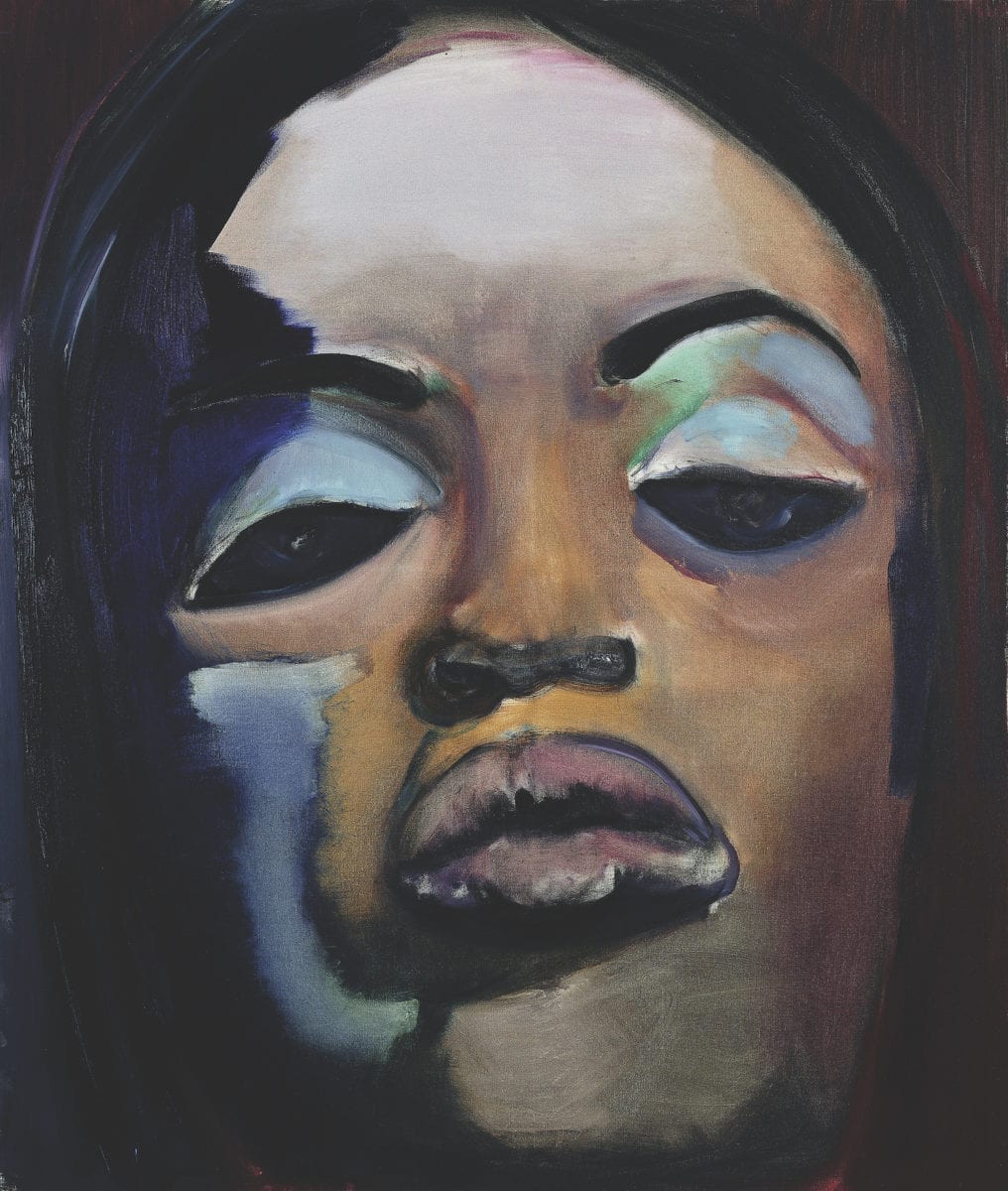

Overtly political works are juxtaposed with paintings of cultural figures like South African artist Moshekwa Langa, film director Pier Paolo Pasolini

and supermodel Naomi Campbell. “When we went through her two archives together—one is her personal work of sketches and drawings, and then there’s her selection of pictures from magazines and films—the interesting thing you notice is that she keeps coming back to these media materials and shaping them into a story. In her early work she incorporated film stills and pictures from magazines, so she has all these mixed-media pieces dating from the 1970s.” The initial idea was to compare Dumas’s image archive with her portraits. “But then we made the decision not to show pictures next to paintings. We felt it may encourage comparisons that we weren’t keen on,” says Coelewij. Despite a lack of direct contrast, the function of photography as a source in fine art is examined through portraits such as Amy-Blue, a close-up of singer Amy Winehouse’s face with her trademark eyeliner and beehive painted in watery blues.

Dumas’s near-pornographic paintings of girls in various poses and states of undress are among her most controversial. The graphic images have sometimes drawn shocked reactions, but Dumas’s aim was not to sensationalize but rather to encourage a dialogue about women working in the sex industry. Modern femininity is also examined through Dumas’s more autobiographical pieces. Her late-1970s works show a psyche burdened with angst and uncertainty. “During that time she’s coming to terms with being an artist but dealing with being new in a country that she didn’t know [Dumas had just arrived in the Netherlands]. There are some funny pieces like I Won’t Have a Pot Plant, because she saw all these plants in the windows on the streets of Amsterdam and she thought: I’m not going to be like this.” It’s one of the most self-referential pieces in the show, highlighting the stubborn reaction of a young woman finding herself on her own in a metropolis.

- Left: Naomi, 1995: Right: Moshekwa, 2006

Coelewij was keen to look at Dumas’s consistent focus on death. In 1978 Dumas created a piece two-and-a-half metres high on paper that combined blueprint drawings with collages of photographs and magazine clippings showing dead people, injured terrorists and victims shot at funerals: “Marlene’s work is related to this idea that the image is loaded, it gives meaning, is political, has a story. Death is a reality that she sees. She knows how powerful different types of image are. It’s not something she deals with in a light-hearted way.” The show will also examine Dumas’s habit of working in series, displaying an ongoing project initially created for Manifesta, a collection made in reaction to Russia’s recent anti-gay laws featuring portraits of famous gay men from recent history, including James Baldwin and Rudolf Nureyev.

“Marlene’s work is related to this idea that the image is loaded, it gives meaning, is political, has a story”

For the exhibition, Coelewij and Dumas worked in partnership with Tate Modern, and in early 2015 The Image As Burden will travel to Tate in London and the Beyeler Foundation in Basel. The majority of the pieces on display will stay the same but the opening room of the Tate Modern iteration of the show will be a series of drawings, Rejects. Helen Sainsbury, co-curator of the Tate show, is particularly proud of this room: “We find it fascinating that you have this real quality of manipulation and evolution in the images—it’s such an interesting side of her way of working. Her voracious appetite for sourcing new mediums is one of the things that make her so relevant.”

The Image As Burden, 1993

“We wanted a new emphasis,” says Coelewij. That’s certainly been achieved. Some of the pieces have never been exhibited in the UK or Netherlands, and the exhibition will feature over 100 drawings and paintings. Dumas’s first show at the Stedelijk was over twenty years ago now, in 1992. Nevertheless, Sainsbury still sees Dumas as fiercely relevant in 2014: “Since the late 1980s and early 1990s her engagement with the world around her has been quite phenomenal… She’s a highly controversial artist; to say she’s not afraid to engage with social and political issues is an understatement. And it’s interesting that for an artist who paints in such a figurative style she doesn’t shy away from opinions. It makes her very potent in our political climate.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 20

BUY ISSUE 20