From fetishistic photography on eBay to the strange intimacy of gut-like corset interiors, Lydia Eliza Trail speaks with Martina Cox to unstitch the artist’s solo exhibition Waist Management, which examines the politics and humour of shaping the femme form.

In her show Waist Management, New York-based artist and seamstress Martina Cox demonstrates her reverence for sartorial history with works created from obscure eBay listings for Victorian fashion artefacts. Cox previously ran a clothing business that produced work at the intersection of surrealism and fashion history, which was stocked with the inimitable Café Forgot. She is currently the organiser of the mending club Darn it! Waist Management is her first solo show with Alyssa Davis Gallery.

When I arrive at Estonian House, there is a party happening. Martina has to rescue me from the mock Tudor-bethan mahogany entry hall. She leads me upstairs to the show, which is held in another period-style imitation room adorned with Grecian trompe l’oeil and vividly painted walls I will inarticulately describe as neon blue. “I don’t know why I started collecting bustles”, Martina tells me, “I just thought they were formally hilarious.” Cox is wearing a vintage skirt that we both agree is shrimp-like—anthropomorphic and reminiscent of a time when clothing was intended to pad, shape, and constrict. We talk about her adventurous bustle search: “It took me to the Victorian re-sale internet. I was immediately attracted to the bizarreness of bustles and the way they were photographed.” Looking at her source material for Waist Management, I can only agree with her when she describes the photos as “almost fetishistic.”

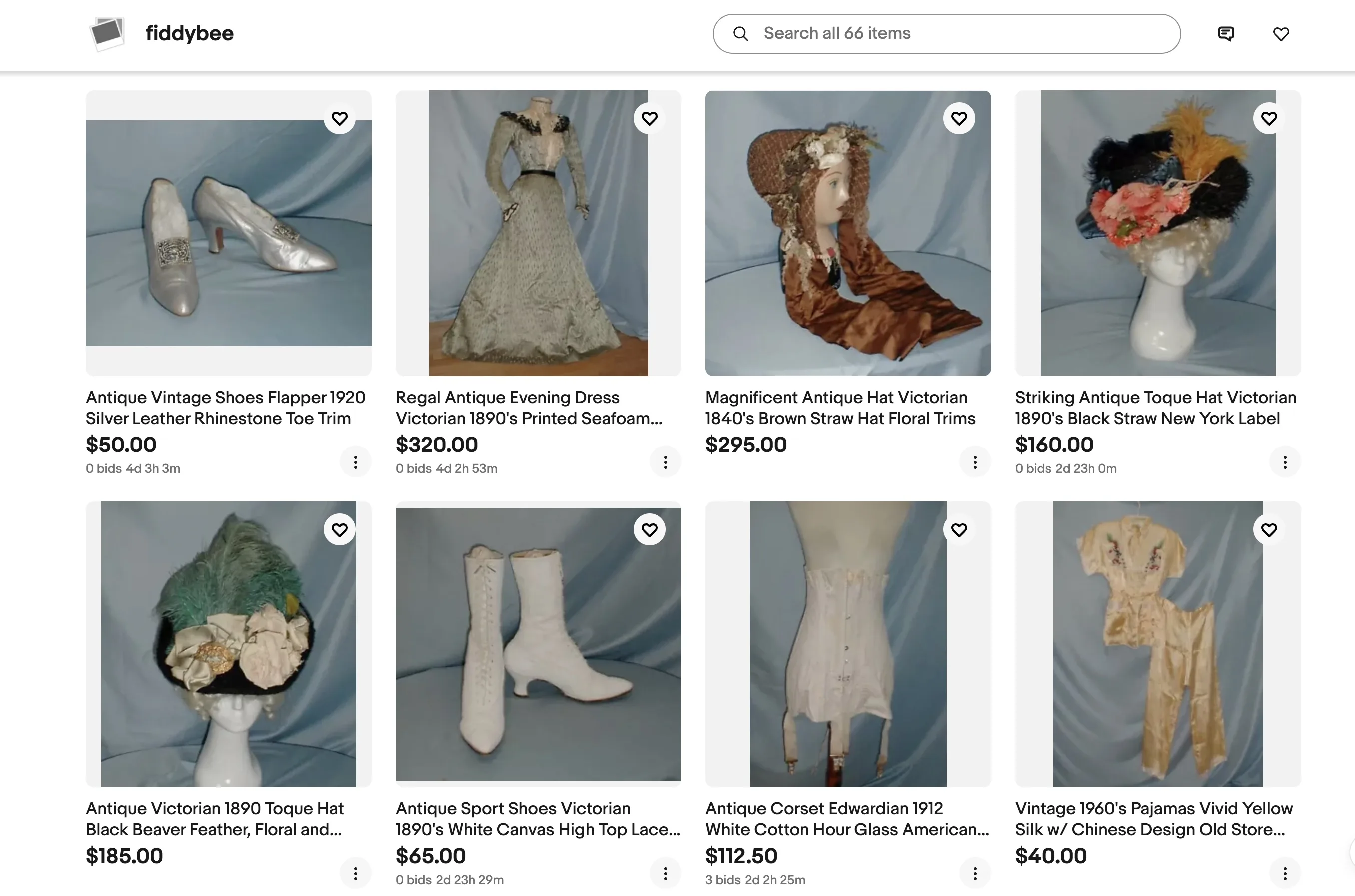

The exhibition’s standout is Cox’s watercolour and pencil series Gut Flora I-IV, which illustrates the interiors of 19th and early 20th-century corsets and bodices. Cox uses the colloquial industry term “guts” fittingly; the images capture what is supposed to be unseemingly and messy, spread out as if by a lepidopterist. Her favourite seller on the digital Victorian market goes by the username Fiddybee, and specialises in a particularly ethereal display, capturing their garments with amateur flash photography against a blue satin backdrop. “I feel as though there was a time when I collected a lot of fetish photography from Flickr that had a sheen to it,” Cox tells me; the stylised image combined with the historical significance of a turn-of-the-century garment form one hell of a digital muse.

Throughout the room are small sculptures made from various bustles, also purchased from Victorian re-sale websites. The sculptures’ names are eccentric: Horse Girl I-III, Angelika, and Royal Ruth, objects that recall the feminine through proximity (these little cushions sat just above one’s buttocks). Anthropomorphising these bustles with anime eyes and beading is not just an attempt to make them kawaii. Rather, Martina’s work comments on the gendered history and shaping of the femme form; while adorable, the sculptures reference comedic illustrations of the time which often mocked women’s absurd silhouettes, with bustles causing women to resemble horses, snails, and crustaceans. Cox’s “Little Shrimp Babies” are precious mementoes to long-departed sisters, with all their intimacies and their fashion pretensions.

A digital layer exists between the original subject, photographed in an eBay seller’s house, and the artwork. This separation alludes to Martina’s interest in museum conservation and costume archiving—we can observe these intimate objects, but we cannot touch them. Ripped open, the bodice’s internal organs were intended to be up against the skin of a real woman. Often, their eBay descriptions indulge in LARPing—see the details of the bodice depicted in Gut Flora I, a piece whose red striped tailoring resembles human musculature: “Antiquedress.com, #3716 – c. 1890 RARE Red Heavy Linen Summer Outing Ensemble!” and then, “Add a jaunty little hat and a parasol, and she could be on her way to Coney Island.”

Waist Management is a punk rendition of costume history. Cox marries the disjointed aesthetic of turn-of-the-century digital catalogues with a longing for an older, more meaningful craft. She talks to me about how the 1890s heralded the first fashion-orientated body modification. “The femme torso collapses in the ‘20s and becomes this androgynous femme thing,” she explains, “then you turn it back another couple of decades, and it becomes like the 1890s, and it’s super constricting booty-popping silhouettes.” There are equal parts reverence and fetishism for historical clothing in Cox’s work, something she shares with the cult clothing store and artistic project Women’s History Museum. Both Cox and the Museum take antique clothing, museum-worthy artefacts, and give them new life—see this listing for an 1880s bustle-train overskirt. A current vogue in fashion history looks at the Victorian era as the start of extremist body modification in commercial fashion—what Valerie Steele, author of Fetish: Fashion, Sex & Power (1997), would describe as sartorial sexuality.

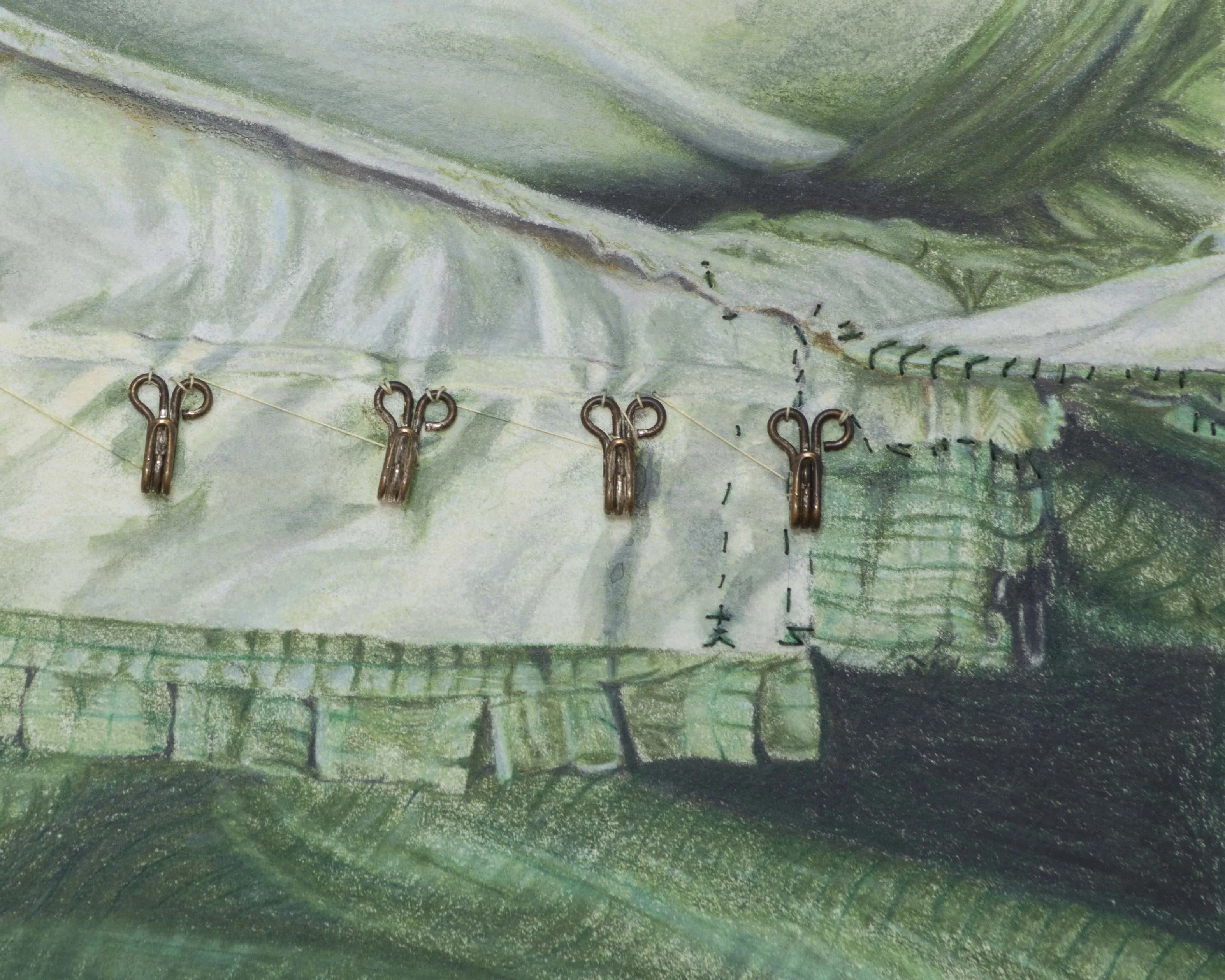

In Fetish, Steele captures the paradoxes of kinky garments. Tightlacing—the practice of corsetry—can be a source of domination and empowerment. While working on Waist Management, Cox had a myriad of references: the performance art of Valie Export, paintings by Christina Ramberg and El Greco, and the Victorian morbid fixation on creating scrapbooks from human hair. She also thought of Kathy Ackers’ 1993 essay Language of the Body, in which Acker describes how bodybuilding involves breaking down muscle to regrow larger, thicker, and stronger, prompting her to ask whether the equation between destruction and growth is also a formula for art. For Martina, the malleability of a woman’s waist is analogous to the bodybuilder’s quest for enlargement: “Bustles, bodices, corsets; these are all sartorial trends that treat the body as something to be morphed, padded and prodded.” There is something to be said for the control over one’s body, inch by inch, that tightlacing offers. In Spinal Top (2024), Cox threaded delicate hooks and eyes through the paper, positioning them exactly where they would appear on the actual garment. Piercing parchment by thread alludes to the actual and symbolic constriction of the corset—an artistic enactment of Michael Foucault’s notion of disciplinary power. The body is controlled through minute functioning, both politically and sartorially.

Cox repeatedly mentions Rozsika Parker’s seminal work TheSubversive Stitch (1984) to me. She sends me photos of the book from her studio with notations. One segment catches my eye, as it illustrates how the lives of forgotten women mark sartorial history: a 1624 poem In Praise of the Needle extols needlework for the fact that it renders women powerless, silent, and still: To use their tongues less, and their needles more.

Written by Lydia Eliza Trail