New York- Martine Gutierrez is a visual poet, an auteur. Her photography (which she stages, models, and shoots alone) articulates the ineffable — the personal and collective truths that get lost in the black-and-white binaries of language laden with cultural undertones.

For the 34-year-old multi-hyphenate artist’s current show at Ryan Lee Gallery, she lifts the veil on a series of nude self-portraits that she originally created as part of a commission from the Public Art Fund in 2021. The series, aptly titled “Anti-Icon,” features Gutierrez channeling famous heroines spanning centuries, continents, and belief systems, including Cleopatra, Helen of Troy, Sacagawea, and Aphrodite, from a pointedly modern, post-apocalyptic lens. She finds fertile ground in the paradox of myths: stories once believed to be true and now understood to be entirely or partly constructed, leaving space for projected fantasy.

Ten of these photographs were displayed across 300 bus stops in New York, Boston, and Chicago. Because of the public nature of the project, sections of the images were veiled: Gutierrez concealed parts of her naked body and rephotographed the images with swaths of fabric strategically draped over her figure.

Now, she is showing the complete series on her terms, without the veils and with an added seven photographs, as a travelling three-part exhibition titled “Anti-Icon: Apokalypsis” this summer, starting at Ryan Lee Gallery in New York from May 18 through June 30. The rest of the large-scale photographs will be shown between San Francisco’s Fraenkel Gallery and London’s Josh Lilley Gallery.

A new American mythology forms as the works in Gutierrez’s series mingle together for the first time on gallery walls. If everything new is made of a composite of the past, then “Anti-Icon: Apokalypsis” gives hope that there are still new compositions to be made.

The artist, who identifies as a nonbinary trans woman, observes the world from a distance: she is a chameleon-like cultural anthropologist with a lifetime’s worth of popular culture references from glossy magazines to science fiction films to repurpose. She has explored themes of identity and representation throughout her oeuvre, including her 2018 project Indigenous Woman, an art book depicting the dual celebration and exploitation of Mayan Indian heritage, and Girlfriends (2014), a series of portraits featuring Martine Gutierrez posing intimately with a mannequin. At a time when trans autonomy is being threatened across America, her photographs serve as a beacon of light, a symbol of beauty and agency amidst an ugly discourse.

Gutierrez took her self-portraits sequestered away, monk like at her mother’s house in upstate New York, against the peeled paint of an empty pool, in the midst of a hot, dry summer; however, the location is not a focal point, and Gutierrez is hesitant to even mention it at all: it could be anywhere, she says. Like her photographs, she possesses a quality of timelessness.

When looking into which characters to depict, she tried to put together a cast that felt diverse. “Generally, I felt familiar with everyone,” she says. “What I realized later was that everyone had one foot in a history book and one in the mainstream media market. She’s in a movie by Disney, and she’s also painted by someone famous, or there’s a poem about her.”

She was intimately familiar with each heroine. She knew their stories, the visual signifiers, and the cultural costumes associated with their names. “It felt important to me that we, for the most part, have an understanding of what this person looks like, the drag of this person, the way, you know, someone can dress up like Lady Gaga now based on the symbols that she adorns herself with big blonde hair and crazy glasses,” she says, eschewing these symbols in favour of a more abstract, pared down, and open-ended interpretation — a futuristic, femmebot framing of the past.

“I wanted to offer an entry point: here’s an introduction to someone that I grew up feeling inspired by, and if you’re not acquainted, it’s time to Google, girl,” she says.

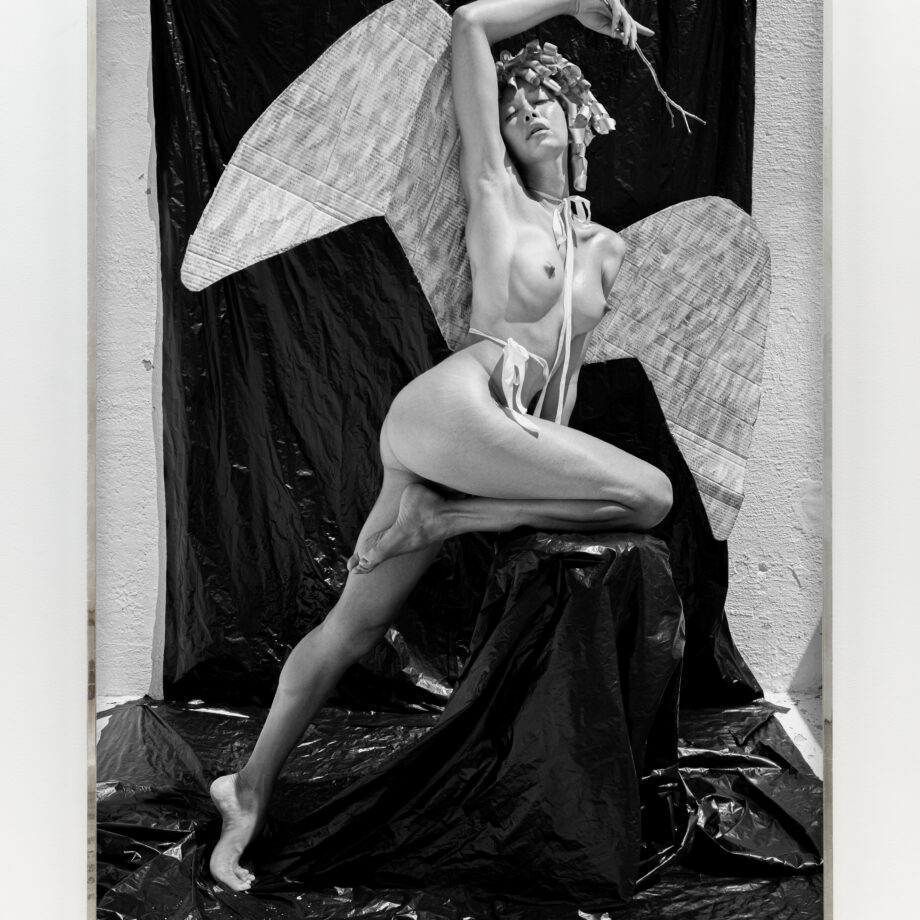

As the angel Gabriel, she dons cardboard wings, one arm resting on her head, delicately holding a twig against a backdrop made from black trash bags. As Helen of Troy, she exudes 1960s Italian glamour, seductively gazing out from behind a veil made of bird netting, a draped tarp clinging to her curves.

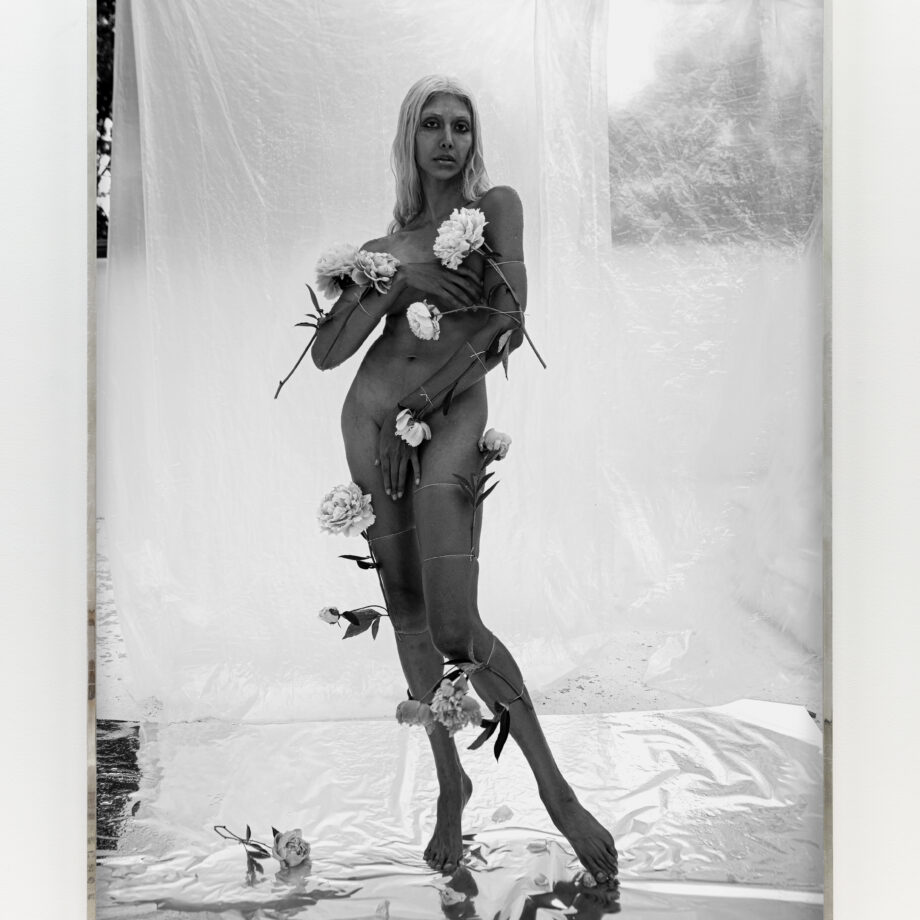

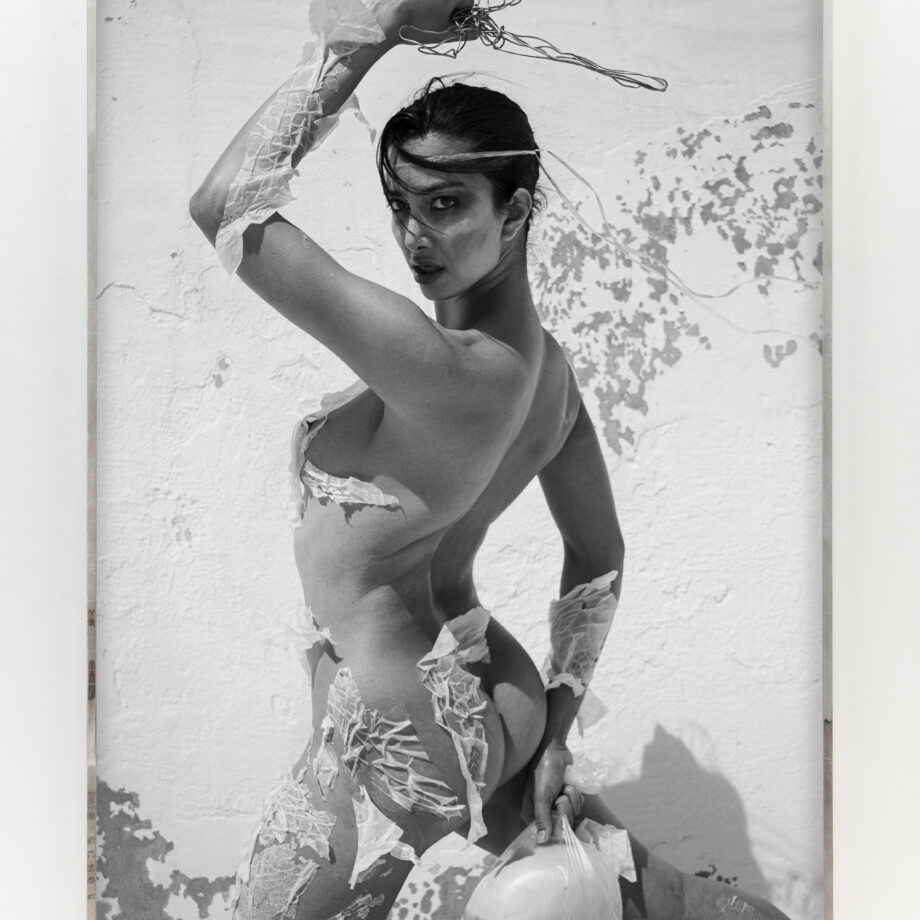

Pale blonde tresses cascade down her bare shoulders as Aphrodite and peonies grown by her mother are warped around her lithe figure with thin string. Mulan’s shield is reimagined as a plaster cast formed from the figure of one of her male mannequins, moulded to have curves while still wet. Her hair is slicked back and “Hershey’s kissed” with a blend of mud and white paint.

In other images, she uses tinsel, fake breasts, a mesh stocking, tissue paper, ribbon, wire, and paint (discarded objects and recycled materials foraged from her mother’s house) to transform herself. The one constant: her steady stare that contains multitudes, a personal story of transformation wrapped up in stories of those who came before her. Now, two years after the images were taken, she traces this collective experience back to nature.

“All of us are much more similar to trees,” she emphasizes. “We’ve put so much emphasis on creating these hierarchies of beauty and perfection, but everyone’s body is so different. We truly are individuals.” She attributes this return to a primordial synergy with the land to a long, smouldering month in Southern Mexico last year, when she frequented a nude beach while shooting an X-rated film, “Rotting in the Sun”, with the Chilean director Sebastián Silva, set to come out this summer.

Here, on the shores of Oaxaca, north of her father’s ancestors in Guatemala (where she would visit her father’s mother high in the volcanic mountains as a child), something was awakened in her as she gazed at the range of naked bodies against the blue skies and rocky coast, free of the capitalist gaze that forces our fleshy skin into fabric confines, waist cinchers, and cover-ups.

“What does it mean to be nude?” she asks. There is a difference in aspirational nudity and human nakedness, she observes. “I honestly felt liberated after filming. Seeing my own naked body around so many other bodies, I realized that I am just an organism.”

With a new appreciation for “the body we all wake up with; the body we go to bed with” Gutierrez returned home from filming to revisit her works that had lay dormant, tucked away safely from the world.

“Initially, I never thought I would release these pictures as is, to be honest,” she says. “I took them myself, alone, and because of that, I was less self-conscious. I knew that I could delete them or keep them on some hard drive forever. I was still in control of how it was going to circulate, who was going to see it — and even how much of my body I wanted to show in the end by veiling them.”

Then, she had an epiphany that came in the form of liberated nonchalance. “I thought, what’s the big deal? This is my body,” she says.

Gutierrez never thought the project would have a second life until then.

In the days leading up to the opening, as she finalizes the installation, she takes a break to reflect on how far she has come. “It’s strange looking at myself, knowing where I was at with my own confidence and seeing how far I’ve come already in my own journey,” she muses outside of the gallery as the bustle of the city reaches a crescendo in the background. Only a few days later, the doors of the gallery will open to the public, inviting visitors to enter her world.

“What does it take for a belief system to be to be considered true or to be in power?” she asks. “Years and years and years and years of genocide, and war, and money,” she answers, pausing before adding, “but also art. Whether it’s painted on the ceiling or presented in stained glass or carved out of stone, you have these depictions that date back older than any of us, and it’s nice not to feel so small.”

Words by Meka Boyle