History, mythology, literature and fantasy collide in an exquisite cacophony in the films of Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley. Their works revel in the artifice of their crude black-and-white props, grotesque prosthetics and erudite rhyming scripts, which are laced with lewd puns and smutty double entendres. In these outlandish creations, Mary assumes all the main roles—which have included a female Minotaur, a submariner in drag and a syphilitic French prostitute—and imbues them with the campy excess of pantomime.

“We’re not interested in flawlessness,” she says in a joint interview on Skype with her collaborator and husband Patrick from their home in Olivebridge, Upstate New York. “We don’t want to over-polish.”

“We’re always resisting the temptation to slip towards the perfectly receding horizon of realism that everyone is familiar with from watching TV and movies,” Patrick agrees. “We’re much more interested primarily in the language and the text that Mary writes and then everything following that is an armature, which means that we’re already in some formalized world because the language structure is not real.”

The artists will have a major solo show at Studio Voltaire in London next month, following on the heels of their 2017/18 exhibition Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley: We Are Ghosts at Tate Liverpool and the Baltimore Museum of Art. For that touring show, they presented their two most recent films This Is Offal (2016) and In the Body of the Sturgeon (2017), which both take their starting points from very different nineteenth-century writings and address themes of ghosts, death and the plight of the marginalized in patriarchal societies.

“Of course, what the Greeks valued was this proportionally very small body. You don’t realize that fully until you try to make a penis suit yourself”

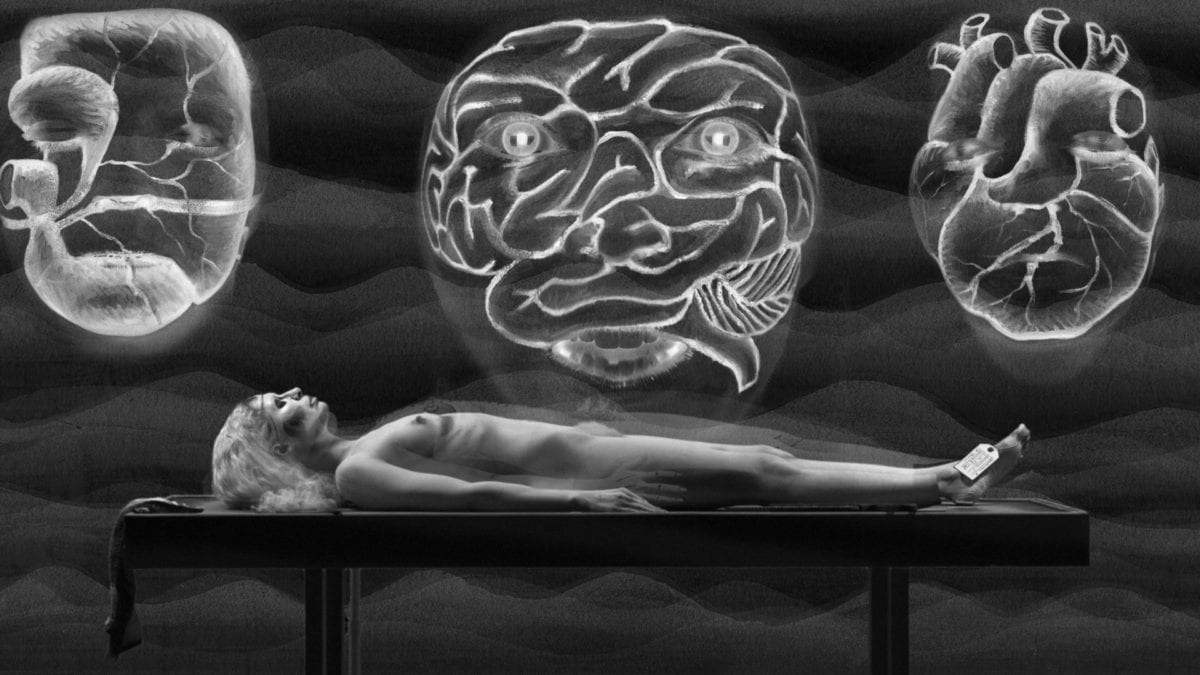

This Is Offal was inspired by the British poet Thomas Hood’s 1844 poem “Bridge of Sighs”, which is about a young woman’s suicide and combines performance, animation and drawing in a highly farcical account that yet manages not to lose sight of the tragedy of the circumstance. The action takes place in a morgue, where disembodied internal organs engage in a verbal slanging match over the victim’s dissected corpse. “What are you, the Beethoven of organs?” the liver taunts the heart, which retorts, “I’m the heart of the matter!” The woman’s ghost sits up on the autopsy table to reflect on her plight, while in a wall cabinet, a dismembered foot and hand rebuke the other organs in Punch and Judy style banter. “What cranium could hold such malice, and treat a faithful foot so callous?” the foot asks the brain. Mary plays all the (body) parts and Patrick performs the role of coroner.

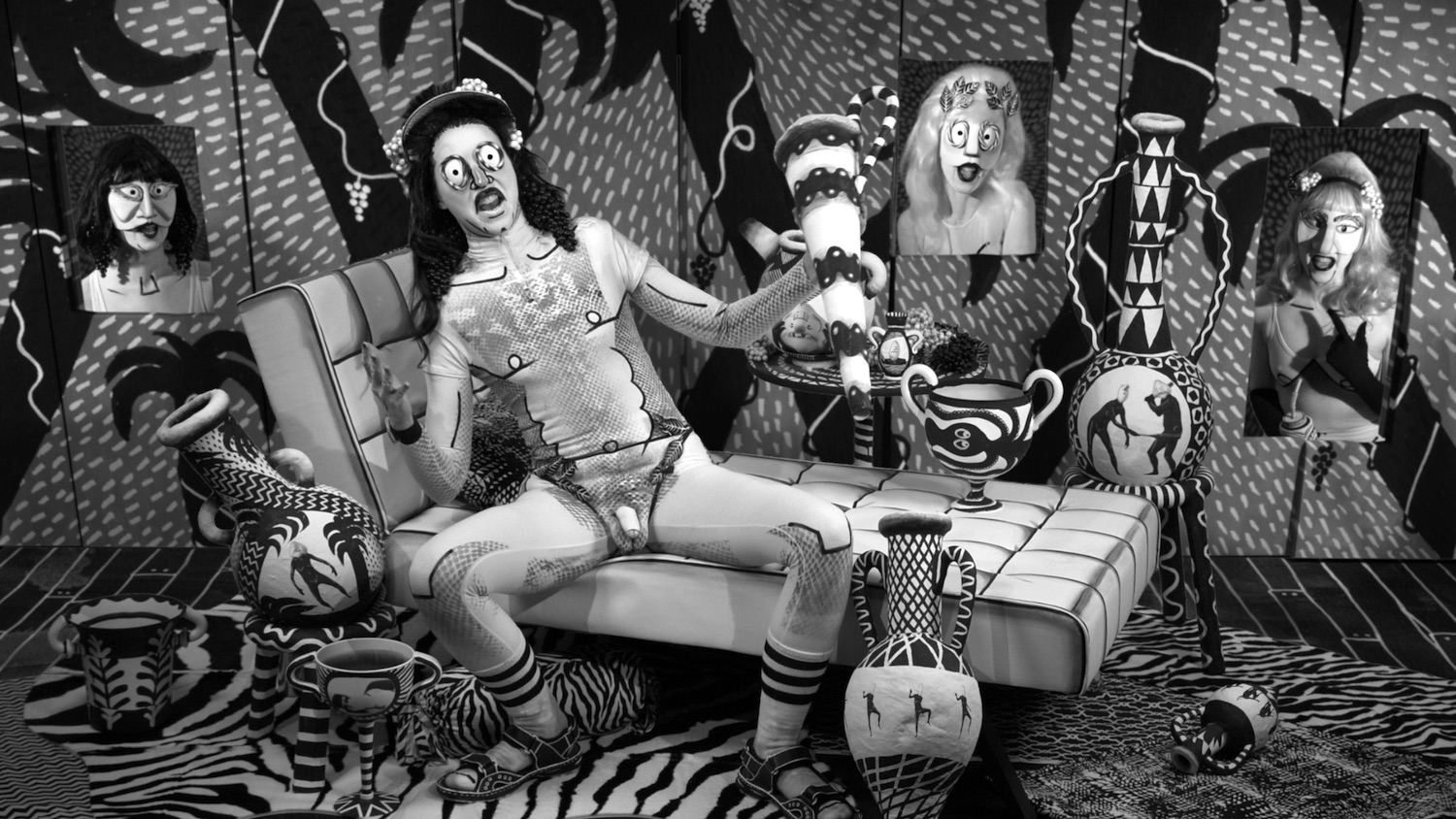

- Mary Reid Kelley & Patrick Kelley, Priapus Agonistes, 2013. HD video with sound, 15 mins 9 sec

In contrast with This Is Offal, for which Mary wrote the original script, In the Body of the Sturgeon is entirely stitched together from a patchwork of text from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic 1855 poem “The Song of Hiawatha” about a Native American warrior in upper Midwest America in the sixteenth century. The reworked text is surreally overlaid onto a tale about sailors aboard the submarine USS Sturgeon in the Pacific near the end of the Second World War. The crew battle their ennui by concocting moonshine and performing burlesque even as President Harry Truman announces the bombing of Hiroshima. The film, which is narrated in the trochaic tetrameter and old-fashioned language of “The Song of Hiawatha”, marked a shift in the artists’ subject matter from Europe to America, and to the cento, a type of poem constructed by rearranging another author’s words or groups of words. “This idea of making something entirely from parts has been long brewing in our work. We’ve always been fascinated with the idea of spolia, this architectural mosaicking, and we were both drawn to going back to an actual historical setting,” says Patrick.

The jarring fusion of two such distinct and mythologized epochs works, perhaps because the subjects both have their fates imposed upon them by higher forces: the sailors are at the mercy of US foreign policy and the Native American hero has his romanticized story patronisingly told by someone from the white ruling class. Mary’s close study of “The Song of Hiawatha” revealed that Longfellow actually incorporated his sense of superiority into the poem’s linguistic structure by restricting its vocabulary to express what he perceived as the limited mindset of the Native Americans. “The colonialist and racist attitude is there in what Longfellow chooses to include and exclude,” she notes. “For example, the nearly 32,000-word poem is about people who have family, who fall in love, who lose people that they love, but the word ‘family’ is nowhere. It’s a way Longfellow says ‘Okay, these people have biology but there’s something about true civilization that they don’t have.’” Mary was further struck by the affinities between “The Song of Hiawatha” and the submarine crew after reading a young submariner’s memoirs describing the struggle during long sea patrols to stop the “mask of civilization” evaporating. “This twenty-three-year-old submariner was in touch with how quickly civilization can slip away in a way that Longfellow just wasn’t. So there’s this totally non-negotiable brick wall for Longfellow between the civilized and non-civilized, between the white Anglo Saxon audience that ‘The Song of Hiawatha’ was written for and the Native American people that he was writing about.”

- Mary Reid Kelley & Patrick Kelley, This is Offal, 2016. HD video with sound

Mary and Patrick met around 2001 at St. Olaf College, Minnesota, where he had taken up a teaching position and she had stayed on for a residency after graduating. In 2007 Mary went to Yale to do an MFA in painting and discovered her ability to write in rhyme. “A really big turning point came with the realization not that I could write but that I had to write. It was an impulse that I couldn’t ignore any longer,” Mary says. “Embracing that was realizing that if I stopped self-identifying as a painter and reidentified as a different type of artist, then I could include so much more than I was already doing into my formal practice.”

Patrick’s background was mainly in photography, particularly in the origins of imaging technology, and where it intersected with philosophy and science. Their professional collaboration began almost by accident while Patrick was visiting Mary at Yale. “She decided to just perform one of the short textual pieces she was doing and I had a camera with me,” he remembers. “I set it up in character with makeup and it just completely evolved from there.”

Mary started out playing all the roles in their work by necessity, but with time this became a core feature. “There’s a strange concentration, like a hall of mirrors doubling that happens when you see me repeated so often. Of course at this point it would be easier to hire other people because of all the work the composite takes,” says Mary. “I think there’s something nice in getting to say the words that I’ve written. There is a feeling of integrity, like when you know that the only person who writes Jay-Z’s lyrics is Jay-Z.”

- Mary Reid Kelley, In the Body of the Sturgeon, 2017. HD video, duration 12 mins 16 secs

The duo immerse themselves in intense research for each project, which can take up to three years to complete. Their division of labour is mostly clear-cut: Mary writes the script and is responsible for makeup, costumes and sets, while Patrick takes charge of building complex props, filming, animation and editing. The artists have certain essential rules governing their work: the restriction to a black-and-white palette, of speech to verse and of the whole face to a drawing, including the eyes. “You can paint every surface of the face except the eyeball, so that’s why they have to have a prosthetic—and also because the eyes are so expressive, they really do give it away,” says Mary. So characters wear ping pong balls for eyes, along with wigs, masks and painted costumes. The cartoonish artificiality is conducive to exploring grotesquerie and taboo themes.

“I think there’s something nice in getting to say the words that I’ve written. There is a feeling of integrity”

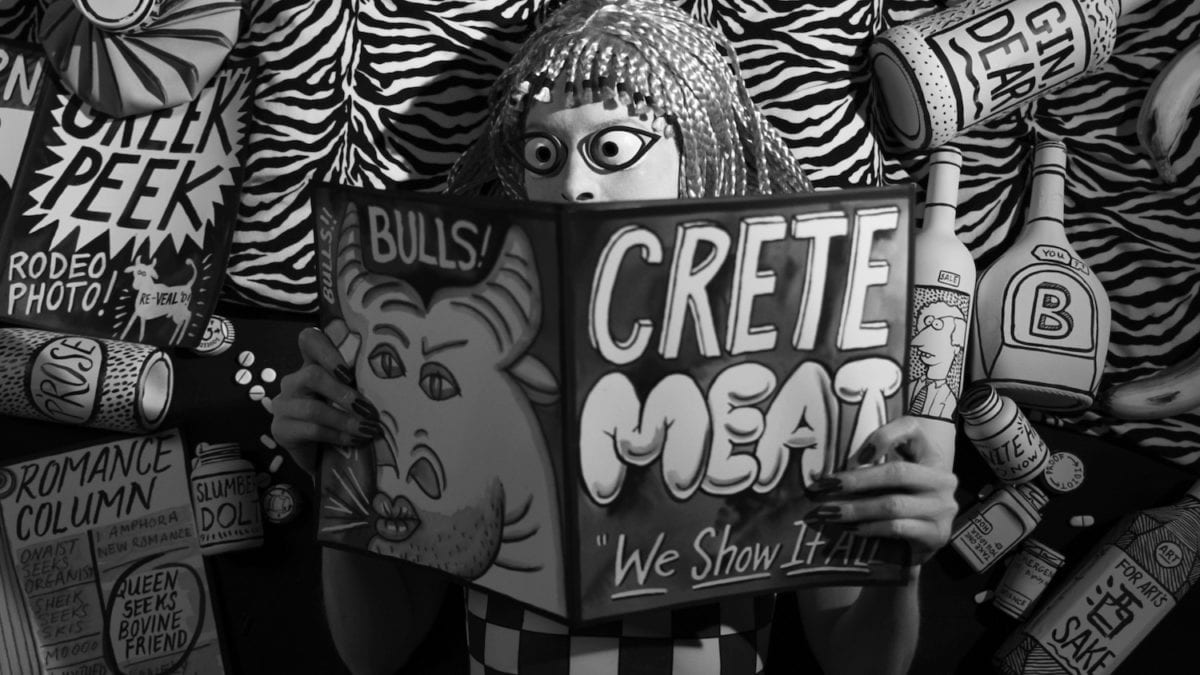

Bestiality, for instance, gets rollicking treatment in the artists’ trilogy of films around the myth of the Minotaur, whom they cast as a female, the offspring of Queen Pasiphaë of Crete and a bull. Characters are heavily and hilariously sexualized. The Minotaur and Greek chorus girls sport exaggerated pubic bushes and the saucy Pasiphaë struts her stuff with painted on butt cheeks and cleavage. Mary explains, “I’ve always been aware that the female and the male are turned into comics in a very different way. There’re just many many more varieties of male figures. Part of the only way to grotesqueify the female is to tongue-in-cheek play off the traditional female characteristics, like the painted cleavage, but also making some new ones like the crazy fringed pubic hair, which would not make it as a mainstream characteristic.” Yet she has learnt the hard way—all puns intended—that when it comes to phalluses, big is not always best, even in caricature. “When I make the penis suits I always have to remake the penises as they’re always too large,” Mary laughs. “Of course, what the Greeks valued was this proportionally very small body. You don’t realize that fully until you try to make a penis suit yourself.” “Everyone should try this,” her husband quips.

- Mary Reid Kelley & Patrick Kelley, This is Offal, 2016. HD video with sound

If the The Minotaur Trilogy sounds like the British Carry On series with a mythological twist, it’s not. At the heart of the trilogy’s bawdiness is the tragicomic character of the lonely Minotaur who wanders her labyrinth, uncomprehending her family’s abandonment and deluding herself that the insults scrawled on the walls by her victims are in fact adoring tributes. Any artist who interprets the Minotaur must contend with the illustrious lineage of its depiction in art, the most famous being Picasso’s intensely personal portrayals of the beast as a vulnerable figure. Working on the film gave Mary a deeper appreciation of Picasso’s radicality in countering the prevailing narrative. “We think of Picasso as being a pretty aggressive person, a misogynist, so I was just really touched by that paradox. He makes a whole island of Minotaurs so they aren’t alone, but they’re still shut out of the human world. That is more or less the template I borrowed.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 37

BUY ISSUE 37