Ursula Mayer isn’t afraid to tackle big, complex issues in her work—and she strolls into them in our conversation as breezily as if we are pondering what to have for lunch. She’s open, talkative and often very, very funny.

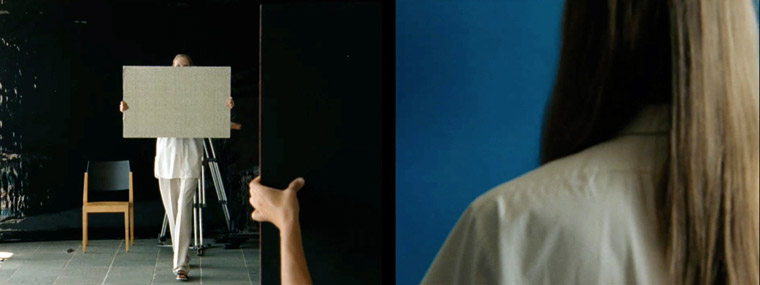

Mayer, who won the 2014 Jarman Award, recently completed a piece for the Istanbul Biennale starring her longtime collaborator Valentijn de Hingh, an Amsterdam-based trans model and activist who the artist has featured in various films including the striking Gonda—a single-shot slow-motion portrait that was screened as part of Channel 4’s Random Acts series, and shot on one of the first sixteen-millimetre cameras that enabled filming in slow motion. For the Istanbul project, Mayer explored her interest in idle animations, as seen in video games as an avatar waits to be used by a player, shown perhaps tapping their feet, or breathing fire. In the work, she recreated these moments in real human form, with Valentijn as the “avatar”. This meant carefully rigging the model so that she appeared to be hovering—looking as though she was animated, able to perform superhuman acts such as creating flames from her hands—presented on a screen as a short looping moving image piece.

“I tried to create an in-betweenness of human and technological entities”

Mayer’s work often pushes technical boundaries (for the Istanbul project she collaborated with the VFX studio that’s previously worked on films like Star Wars), and her methods match her thematics, in that they push notions of what it means to be human in a technological age. I spoke to her about what all this means, her artistic explorations around consciousness and more.

- Ursula Mayer, stills from Atom Spirit, 2016

Can you tell me a bit more about how your work explores the relationship between humans and technology, and vice versa?

I’m interested in how we evolve as humans in general; it’s unavoidable that we’re evolving together with technology. But I’m also interested in how we are evolving in terms of our consciousness and spirituality, looking at the condition of humanity in the moment—technology is just one part of that. My work often relates to evolution in terms of how we perceive gender, and how gender is a performative thing. We have to move on from these binary systems. So if I talk about consciousness, that means tapping into something bigger, related to things like the eternal self, and the bigger cosmic order: everything is connected through consciousness.

“My work often relates to evolution in terms of how we perceive gender, and how gender is a performative thing“

In a way to realize that is also to realize the self, which is an eternal thing: it’s not what we think we are. Our stories, our perception of ourselves in terms of physical entities, our appearance: it’s the soul, and the soul’s purpose of how we came here and evolved as humans. It sounds esoteric but it’s not; when we talk about the self, it’s always related to the outside and the performative aspect of it. Obviously I love that side of things and have a very specific interest in the surface. I work with a lot of fashion designers, for example, but I’m also really interested in what’s behind, and that goes into other realms of knowledge, which doesn’t just come from art theory, it could come from reading the Bhagavad Gita or something. I’m interested in the whole kind of philosophy around post-humanism, people like Donna Haraway and Rosi Braidotti—she talks about other forces, and goes into other realms of existence when she talks about post=humanism, and she would describe life as a “force”.

Tech has evolved a huge amount since you’ve started working as an artist, with newer possibilities for animation, software and so on—what do you think the impact has been on artists and art more broadly?

In general, making a film is so much easier now: you can make a feature film on an iPhone, so that’s already made filmmaking so different. When I started around 2004 the whole MTV aesthetic was popping up and video technology was being used in such a popular context. That was followed by a time where people started to work with more “classical” analogue materials again, but most of my work apart from the recent biennale piece has been shot on sixteen- or thirty-five-millimetre film.

“I invite people to work with me when I cast them, so they’re authentic, and presenting themselves”

But [the biennale piece] is more a video sculpture as an endless loop on an LED screen: when you come in, you see the piece from the back and you see all the technology—it becomes part of the body of work, because this figure almost “lives” as an entity in the screen.

Video work and film has evolved with the equipment itself: when you when you show [an analogue] film, it only exists when you turn on the projector, so it’s more an illusion that’s made from a chemical process in shooting the film and the processes involved in making the work. With [digital technology], the aesthetics are already completely different, and you’re working with a different package of cultural history behind it.

Why have you found moving image to be the most appropriate medium for what you want to say as an artist?

If I have an idea and want to work using a specific material, it’s always part of wanting to produce something three-dimensional in a space. That always relates to moving image for me, because it all comes back to narratives. When I make installations that use different mediums, like photography, fabrics, prints or sculptures, I’m still interested in how narrative bleeds into a room and how I can work with that. I call some pieces video sculptures, but I’m not a sculptor—I wouldn’t just make a sculpture because I want to make a sculpture.

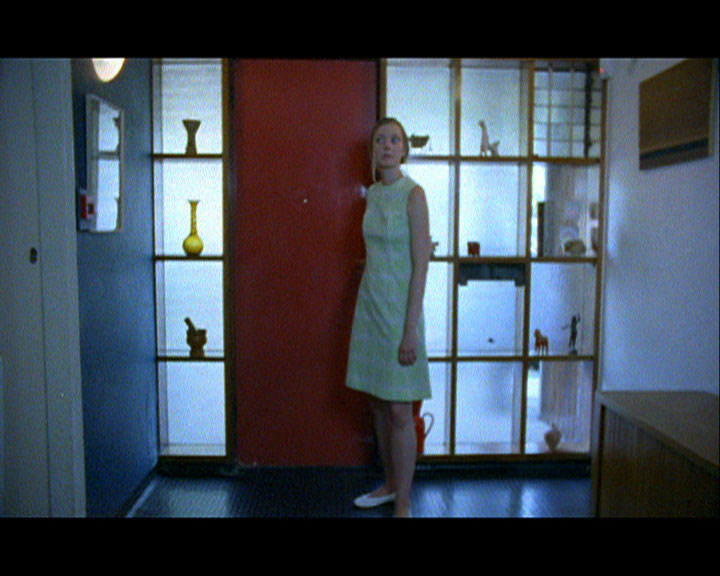

- Ursula Mayer, stills from Interiors, 2006. Courtesy of Ursula Mayer and LUX, London

Can you tell me a bit more about how you approach narrative (or non-linear, non-narrative) in your works?

I’ve always been very interested in how narrative evolves in films and how it can undermine our belief systems. Especially in my early works, I’ve looked at image production and the way you construct an image to undermine certain aspects of what you’re seeing.

I’ve always worked with that sort of metafiction around image-making. For me, it was important to do that using film because it fits with the aesthetic. There’s an early piece where I deliberately make the work look like found footage, so the viewer isn’t sure if it’s something the artist made or not. Another important aspect is how sound and image collapse: there’s never a straightforward narrative in my work, you have to move with the image. In a way, the narrative unfolds by the viewer being open to the process of evolving with the images. Everybody watches a film in a different way, so it has multiple meanings.

“I’ve always been very interested in how narrative can undermine our belief systems”

You often work with non-actors. Why is that important to your films?

With Valentijn, she’s always up for everything: she doesn’t question anything, she just wants to give her best. It’s quite incredible to work with people like that. With JD Samson [who stars in Meyer’s Medea], I always liked her in Le Tigre—she seemed very special. Filmmaking is a collaborative process: I invite people to work with me when I cast them, so they’re authentic, and presenting themselves, even if that’s a fictionalized version of themselves. Even if there’s a script, they have their own voice, and that in turn forms the script itself. It’s always collaborative.