Medrie MacPhee sits down for a conversation with longtime friend and fellow artist Nicole Eisenman on the occasion of her solo exhibition, The Repair, on view at Tibor de Nagy Gallery through April 19, 2025.

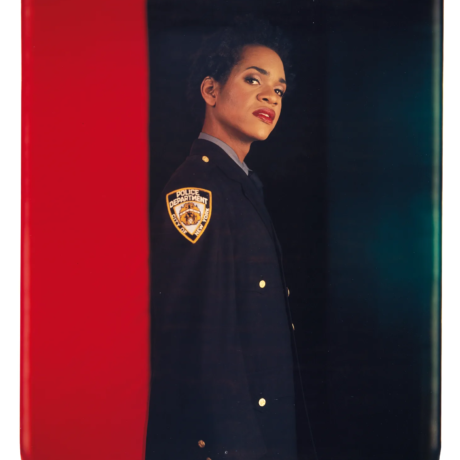

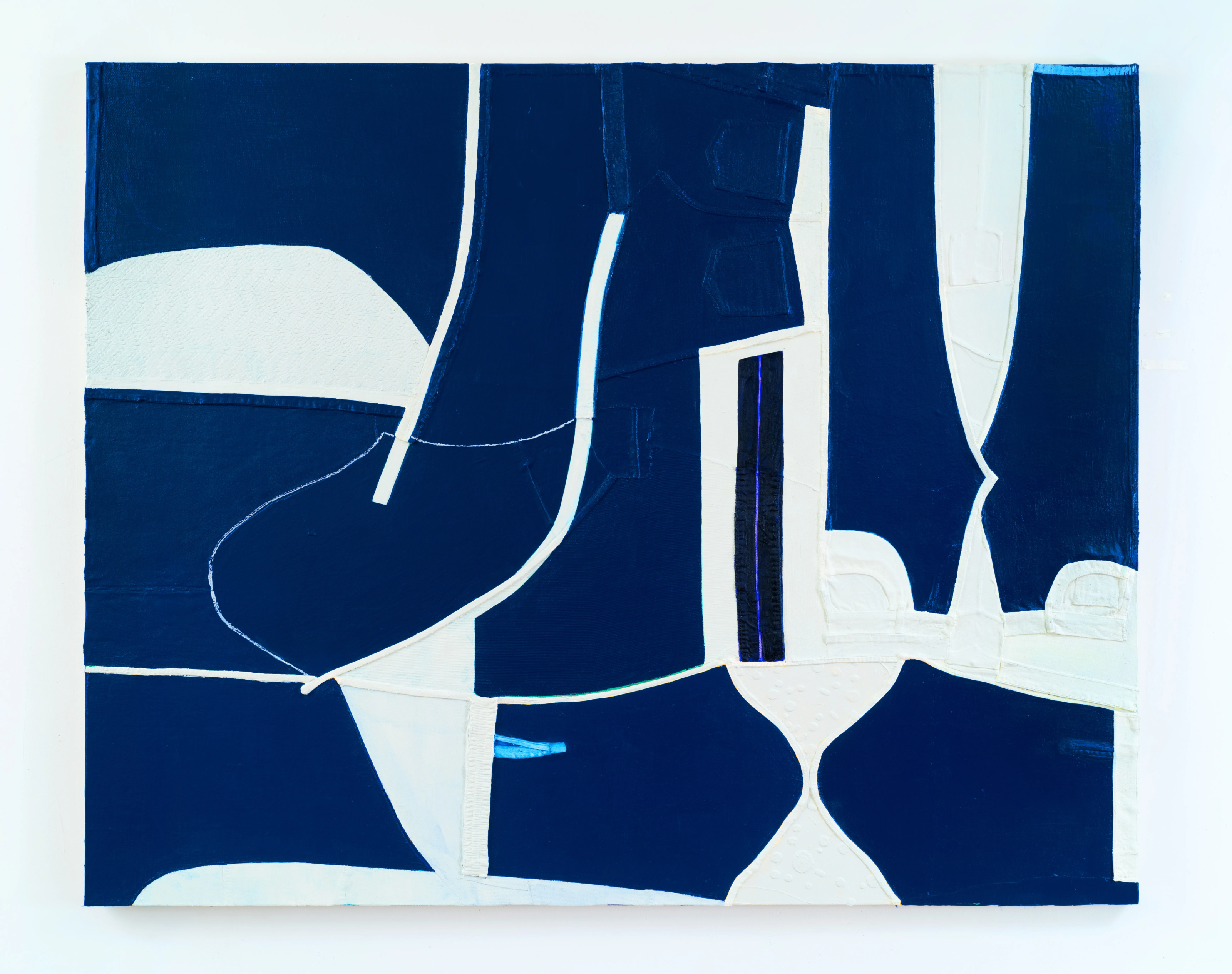

For almost five decades, Medrie MacPhee’s paintings have navigated the space between abstraction and representation. While architecture and demolition were primary references in her early collages and drawings, the artist has turned to the use of ordinary materials – second-hand and discount clothing with its concomitant buttons, zippers, and seams – pasted to the surface of stretched canvas. The result is at once anatomical and topographical: a plane of shapes, seams, and decorative details, unified by a wash of white gesso like a blanket of snow over the landscape seen from a plane window.

While MacPhee’s materials are modest, her ability to wield them is anything but. Her sharp instinct for scale and her obsession with preserving a sense of disequilibrium and off-balance tension in the final image reveal the surprising textural possibilities of flatness. She finds the sourcing, deconstruction, and reassembly of discarded clothing deeply satisfying – a process which results in collages steeped in memory, material history, geometric potential, and a quiet, overlooked poetry.

MacPhee is also Nicole Eisenman’s good friend and unofficial “paint doctor”. The two met in 2002 while teaching at Bard College, and during the long drives they shared from the city to the campus, they compared notes on the exhibitions they had seen that week. The artists began to trade studio visits, advice, and coffee, and the rest is history.

In this conversation for Elephant, MacPhee and Eisenman cover the false binary of abstraction and figuration, regret and purpose in life’s last chapters, what a world without signs might look like – and the violent acts of “painticide” they commit when a work doesn’t come out quite right.

Medrie MacPhee: I got a short text from an artist friend, Ruth Marten – she was one of the first female tattoo artists in the States. She’s also a graphic artist and a painter. Anyway, she wrote to me about the show, and she said something that I thought was interesting. She said, “Perhaps the elements being actual clothing and our second skin, the paintings bust through the intellectual barriers that define abstraction and touch the viewer in a more direct way.”

Nicole Eisenman: That’s wonderful.

MM: That had never really occurred to me.

NE: It’s interesting to think about the second skin as the skin of the surface of the painting. I was just looking at a photo of Maria Lassnig lying on the floor next to her painting of a body. She has her eyes closed – it looks like she’s spooning the figure.

MM: Well, it’s interesting because, you know, I got into all of this in a very backdoor way. But there is definitely something about the material being pieces of clothing. They exist first as themselves – as shelter or a “second skin” for humans – and then they get erased in my process, then they get brought back to life in a different way. But, as a viewer, you can see what often looks like a shoulder, or a leg piece, or buttons.

NE: A top, a sock.

MM: Zippers, pockets. It brings in the viewer in a different way.

NE: These items that are not only familiar but very close to us. There’s this mirror neuron, haptic phenomenon that happens.

MM: Exactly.

NE: Oh, that’s lovely. With the clothing, there’s a limitation – the clothing’s only a certain size. I was thinking about how you cut the shapes. It’s not an additive process; if you don’t like a shape, you can’t re-cut it, rather, there’s only so much. Every time you re-cut, it’ll get a little smaller.

MM: Right, or I can add something else onto it and make it bigger, or change its shape. There’s this thing called a sewing machine.

NE: You’re sewing the clothing before you put it on the canvas?

MM: If needs be, sure – and because they’re glued, not sewn, to the canvas, there’s a lot of shifting around that can happen before I finally decide, “Okay, this is it.”

NE: It looks like you’re giving yourself the freedom to keep the clothing more whole than I’ve seen in the past.

MM: Well, these two on the right [Drawing It Down (2025) and Bob’s Not Your Uncle (2025)] are the most recent, and they’re the simplest in a certain way.

NE: There’s a figurative element in that piece [points to a painting]. The tush of the pants becomes like a face. I see two figures, which are both there and not there. But that’s something that happens in your work a lot. Do you begin to see things as you are making them?

MM: Sometimes I do. Not always. That piece was a complete surprise. I usually paint over the entire surface of a painting, but with this one I didn’t – or I couldn’t. It seemed to want to be recognised in a different way. It sat around while I decided how far to go in changing it. In the end, it’s somewhere between being a painting and a drawing, or almost a bas relief sculpture. A couple of people at the opening came up to me and said, “Oh my God, that painting is so sexual.” And I laughed, “Really?” The shape on the left has these straps that I guess could look like some kind of bondage gear, but I thought of it as more of a straitjacket or something. This is a time in the U.S. where it feels like one should have a breakdown.

NE: Do you search for these associations, or do you resist them? What part of the process is it for you to see imagery in the abstraction? Does it matter even?

MM: I guess it doesn’t really matter, although some paintings lend themselves more to association than others. What I find fascinating is what propels one forward, especially if you’re making an abstract painting. What is the guide? What makes something seem like a good or bad choice that exists outside of just formal problem solving, like, “Let’s balance all this out,” or “Let’s create a symmetry,” or something. There’s something that you want to see mirrored there, but you don’t really know what it is until it starts to manifest. Sometimes it takes time for conscious associations to take place.

NE: These kind of associations come after.

MM: Yeah. That said, if I make an association too quickly, it usually means that it’s not good. I want to undo it. It closes it down too quickly. It seems like my desire is to keep everything in play for as long as possible.

NE: Keep all the balls in the air.

MM: Yeah.

NE: That’s cool. I was reading this document you sent me about your associations with painting and influences. You mentioned [Max] Beckmann and Alice Neel as being influential painters to you, and they both use outlines in their work. Does that resonate?

MM: Oh, that’s interesting. Yeah.

NE: Your lines are often outlines because they’re seams of clothing, and they happen on the edges of a piece of a shape. Often, you use line painted in to disrupt the shapes. So, there are these different strategies to making line.

MM: If it’s a seam on a pair of pants or something, I can either paint it in so it’s opaque, or I can just stain it. It depends on whether the background colours are darker or lighter. Over time, this painting [For The Record (2023-2024)] has started to seem processional to me. It has a sense of movement.

NE: There’s a movement across it from right to left. I am now looking at it as a processional – it leads itself!

MM: And this [A Path of No Return (2022)] I would see as a sort of maze.

NE: Yes. A maze, a space that you’re looking at, top-down, from a distance. I often think of topographical landscapes with your work, but the maze is more specific. The bumping up and having to find another route.

MM: And then you get to the centre of the somewhat ordered maze and things just go pear-shaped. One becomes stuck and there is no way back.

NE: Do you think the processes of making these paintings reflect your personality?

MM: I think they reflect my personality more than anything I’ve ever done, in a way. A personality, even your own, sometimes takes a lifetime to absorb. There is a dark humour for me in the paintings that wasn’t so present or accessible to me in the past.

NE: Where do you see the darkness?

MM: My older bodies of work tended towards the dystopic. With dystopia, you peer into the future and it’s not promising. Not that all my paintings registered this so bluntly, but that was what attracted me and led me. But I was also really attracted to humour – humour as a coping strategy and humour as a way of expressing dark things, but in a way that grabbed you in its paradox – like Guston’s Klu Klux Klan figures in their clown car. I told you once that my English grandparents were vaudevillians. It’s that sort of comical, darkly funny, failing and flailing way that humans stumble along.

NE: I think finding a pair of jeans – these dorky pants – embedded in what looks like these otherwise very elegant abstractions is funny.

MM: On the subject of jeans: one time we had squirrels in the eaves of our house, and this pair that showed up to clear the squirrels out was a tattooed married couple. He was a sweet albeit big, burly guy, and they had to go through my studio to do their work. We talked about the paintings and so on, and the next time they showed up, he brought me a big boy pair of used overalls.

NE: Will you go out and buy clothes for the paintings, or do they have to come to you?

MM: My sources are second-hand clothes, bins in discount stores, my clothes, Harold’s clothes. Friends give me clothes; other relatives give me clothes. I have a never-ending supply.

NE: There is a never-ending supply. A planet-worth of junk clothing is out there.

MM: But with the second-hand clothing, I often look for something in particular. I feel like I’ve exhausted my repertoire of sweatsuits and that kind of thing. Now, I often look for something that, in itself, is a bit odd. It has some odd or interesting notion attached to it.

NE: How does it feel to look at them when you’re done? Do you accept them as they are, or do you sit there and think, “Oh, I could have done that?”

MM: No, no. I really do feel that they’re done. They’re definitely done. I wouldn’t touch any of them, and I don’t always feel that way.

NE: I always get asked how I know when a work is done. It’s hard to answer.

MM: It’s impossible to answer.

NE: Maybe we should try to answer that.

MM: I think I’ve gone there – where you’re looking for something, and then it manifests in some way. You see it, and it feels like you can walk away from it. It doesn’t always work, but maybe that’s just the initial thing. Sometimes, if I’m too easily satisfied with something, I know it’s going to be a dog in a week. It’s usually the things that I’m excited about but perplexed by, when I’m like “This could be something, but I’m not sure,” that are the best.

NE: You have to really sit with it. It’s not just a constant putting down and taking out and erasure and destruction and construction. There’s a really serious period of just looking and resting for you.

MM: Yeah. Just keeping stuff around, moving on to another piece, when I haven’t made up my mind. And I destroy work too sometimes.

NE: Woah. You’ll take it off the stretcher?

MM: Oh, it’s worse than that. Because, you know how you can be like a dog with a bone in a painting, where it’s a fight to the death?

NE: Yes, I do.

MM: Where you keep trying and trying and trying. Then, you know, at a certain point, it’s just –

NE: A dog.

MM: A dog. So, what do I do so that I can’t back out? I take a single-edged blade, and I just cut it right down the middle. That’s it. Gone.

NE: Violent!

MM: I even did that with an eight-by-ten-foot painting a couple of years ago. I’d been working on it for a really long time, but you know how it is. It’s sort of like you don’t know what’s happened. You turned a strange corner or something.

NE: And there’s no resolving it.

MM: There’s no going back. It’s dead.

NE: It’s painticide!

MM: Or maybe it’s something even worse: you’ve made something that looks like art, but you just feel like, “Nah.”

NE: What can often kill a painting is when you paint over and over it, and you start seeing these paint marks. Then you paint over it with another colour, but you see the brush texture underneath it – the surface becomes clotted. Instant painting death.

MM: Yeah, exactly.

NE: It can look terrible, but you can do something where you use that in a smart way to see the evidence of what’s under the shapes… I remember when we taught at Bard together, we used to look at student paintings. We’d see all these clotted surfaces and say, “What the hell! Start over!”

MM: Yeah. Really, it’s just terrible.

NE: Is a substructure something that you might think about as you work? Do you strategize?

MM: Not really. Except sometimes, when I have it all mapped out and I realise that there’s something about the underlying structure that’s just off, then I might just tear the piece off and put something else on, even pretty far along into the process. It’s a stupid activity – not stupid, but that was what I was trying to get at when I was describing how I was making them. You have to just accept whatever it is you’re doing. I remember, one time I came to your studio, and you were making paintings with insulation foam.

NE: Expanding spray foam.

MM: Yeah. That just killed me. I loved it so much, but just this idea that you know that you’re involved in something that –

NE: It’s really dumb.

MM: It’s really dumb, but then you’ll be damned.

NE: The worst material ever. When I came in here at the opening – first of all, it was packed. It was amazing. These paintings already overwhelm the space. It just seemed like the densest possible space in New York City at that moment. The paintings want a lot of attention, and there’s a lot to look at in this space. My friend, Ambera Wellman, said that they looked really youthful. They feel very alive. They swim around you.

MM: I like that. It’s interesting, there’s a lot to feel regretful about when you get into your last chapter in life, but there’s also a strength of purpose or something where you just don’t care as much in a certain way. And those things that you were never sure of before, “Should I try this or try that?” You just think, “Well, why not?”

NE: They’re born of this irreverence.

MM: Yeah. I guess I’m not somebody who’s been consistently doing one thing over all these years. It’s like something has inevitably grown into being something else. I couldn’t even try to stop that. You just have to go where you’re going. I think you’ll become mired and frustrated unless, as an artist, what you’re doing is still really exciting to you and it’s a lifelong preoccupation. There are some people who can keep up the level of exploration. But I think, in some ways, it’s about mapping your own time as a person, and everything you accumulated along the way. All the things you’re looking at, what you’re thinking about, your personal life – it’s all happening around you. That’s the mirroring that takes place, especially for a visual artist. There’s something going on in your consciousness – something that maybe lacks language, that you can’t easily speak of – but it can be exercised in what you’re making.

NE: That’s amazing. Do you see these paintings reflecting your state of mind right now? Your hopes, dreams, fears?

MM: Yeah, I think so. There’s a bit of a gap in time. These ones are the most recent [points to two different paintings]. It’s sort of funny because this one is fairly buoyant in a way, but that one, to me, is different.

NE: There’s more confrontation in it.

MM: Yeah. And like everybody, I’m trying to mentally live in two places right now. There’s your personal life, and then there’s this horrifying shitshow going on around you that you feel somewhat powerless about, but you have to witness and somehow, hopefully, take part in.

NE: I like how flat these paintings are. I remember you and Ulrika Mueller gave me the assignment of making a flat painting. It was a really helpful assignment.

MM: That’s funny.

NE: You took space out of your work.

MM: It was really hard.

NE: Moving from oil paint to cutting up clothing was a huge move, but in that move was the flattening of space.

MM: Oh, absolutely. That was really crucial. I mean, for most of my painting life, I treated a canvas like a window. I was always making space, and you get into the habit of that. I could never have imagined making a flat painting. I just couldn’t conceive of it at all.

NE: I got really stuck on that assignment because anything you do seems to create space. I couldn’t figure out how. I was just pulling my hair out for weeks, and then I called Ulrika, and she was like, “Well, there’s going to be space inevitably, but make it flat space.” And then I was like, “Aha, flat space, you didn’t say flat space!”

MM: Or shallow space. I mean, there’s a shallow space in these, then it also comes down to colours, the size of different coloured shapes, how they play with each other in a way that moves you in and out.

NE: I think the flat ones are the more typographical ones – the blue and white ones. Whereas the others do have a sense of shallow space, a sense of blocking. It’s like when you’re sitting in a movie theatre and somebody walks in front of you, this big shape interfering with the screen.

MM: Yeah. It reminds me also of that tour we got of the Sienese exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in January. We both loved that show, and I was talking about how I remembered seeing Sienese painting in my early thirties when I visited Siena. It was so comical and touching. The paintings were really very flat, but they had discovered one point perspective, so they were able to give you just a little wedge of space to get into it, to experience the narrative and the architecture.

NE: There is a nice parallel between these and the Sienese paintings, actually. The precision too. I think they’re extremely precise paintings. You are our modern Sienese painter.

MM: What can I say to that? I was thinking about all the hours that you and I have spent looking at art, talking about art, looking at student art, travelling to see shows together.

NE: It’s true. I should mention to our reading audience that Medrie is my paint doctor, which means that when I get stuck, Medrie is the person I call on to help me fix things.

MM: Well, ditto. You really just need one person in some ways.

NE: Your practice has had a profound influence on mine, so I think that’s interesting, because we come at it from really different directions.

MM: Yeah. But that’s what’s so strange about even thinking about people whose work has really affected and moved you. Even though it might not look anything like yours, there’s just something that tunnels through that.

NE: It’s true. This kind of split-brain thing – this thing we do between abstraction and figuration is such a false binary. It seemed like something that abstract painters did to distance themselves from history and establish a newness. But it’s not. On both sides, there’s always abstraction.

MM: Well, it’s because… How do I put this? You may understand that the air around us is full. It’s a full emptiness. We can’t see it, but it is. But meanwhile, if you can see, you are walking around in a world full of objects and things and colours and so on. How does that get wiped away if you’re making an abstract painting? It doesn’t. Or the reverse.

NE: Likewise, you can walk around and see that there’s sidewalks and planters and cars and mailmen, and see them just as they are, without the idea of what they are. And then everything devolves into abstraction. So, it works both ways.

MM: Also, I think I was telling you; I just went down a rabbit hole recently where I was thinking, “When did people first start talking to each other? How did that happen? Why? And when?”

NE: Why were you thinking about the origins of language?

MM: I guess because I was thinking about this whole business of abstraction and representation. When I was young, I wanted to be a writer. In a way, it made perfect sense that, at first, I would try to make a picture in the same way I would try to tell a story that couldn’t be told. Just like those early de Chirico paintings that are so weirdly uncanny, you sense something. You’re not quite sure what it is, but it’s very compelling. I was very interested in all of that.

NE: You’re getting pure feeling.

MM: Yeah. And yet, over the past few years, as I’ve gotten more comfortable with doing this, I feel like it’s really been brought home exactly what you were saying; how stupid it is to think that they’re on opposite ends. They can’t possibly be.

NE: These paintings could be the way my cat sees the world – a world where we ignore what the sign means.

MM: Exactly.

Introduced by Alma Feigis.