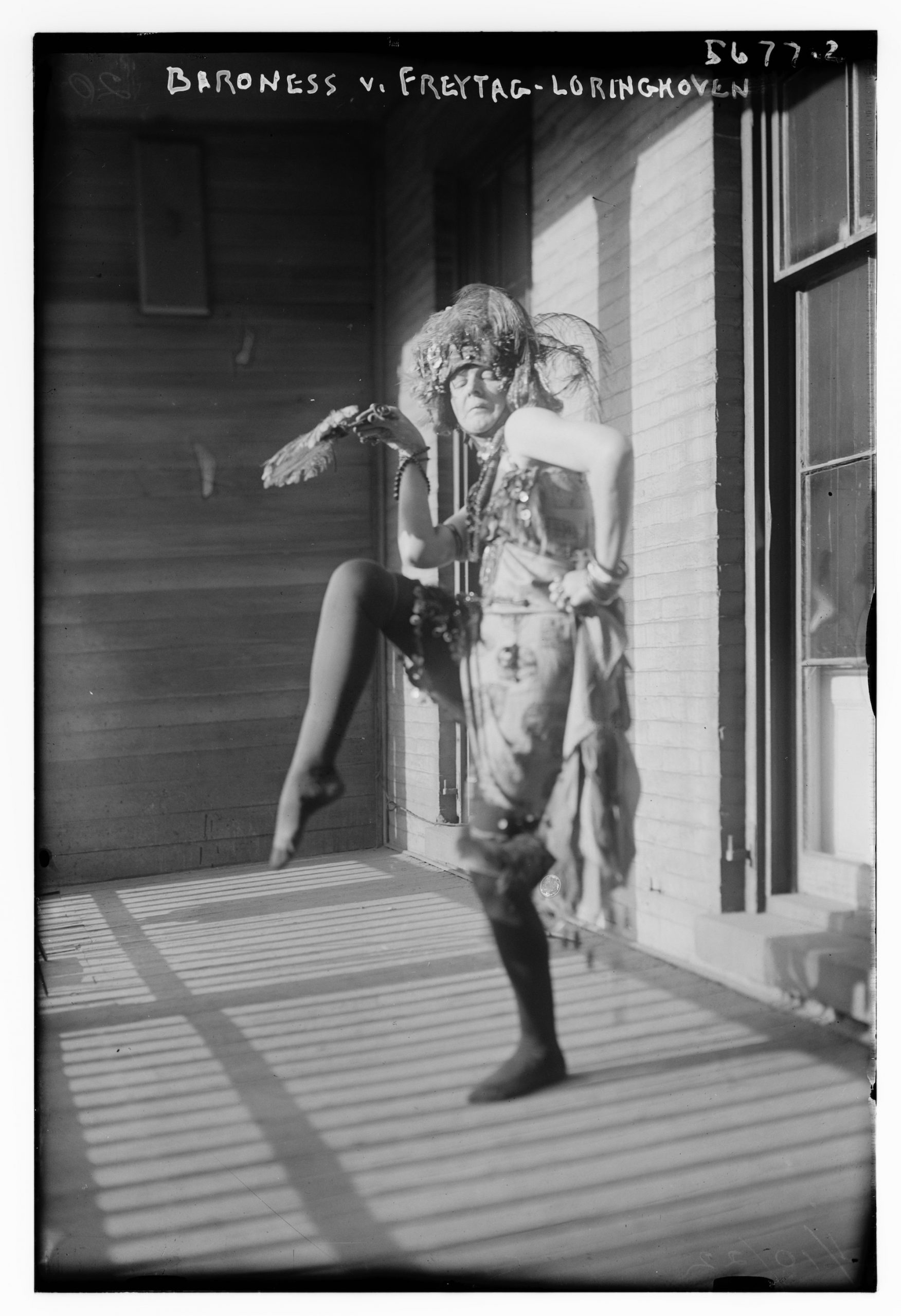

If you heard about a provocative German artist making a name for herself writing experimental poetry about ejaculation, starring in films about shaving her pubic hair, making sculptures from street detritus, and wearing bras made of soup cans, you might think that a new kid had landed on the Berlin art scene. Or maybe that we were talking about some darling of the 1970s performance art crowd.

You’d be wrong though. We’re actually talking here about The Baroness, an artist from the earliest decades of the 20th century. One of the “characters, one of the terrors,” of pre-Modernist New York City as her editor, agent, collaborator and lover Djuna Barnes put it, she paved the way for the provocative, challenging and irreverent contemporary art of today.

Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was born Else Hildegard Plötz in 1874, in the city of Świnoujście, now in northwest Poland. Her title was a memento of her marriage to the German Baron Leopold von Freytag-Loringhover. He was her third husband and this possibly bigamous union (her second marriage may well not have legally ended) was like all of The Baroness’s marriages, short-lived. Unlike her first two, this third partnership did not involve a ménage à trois in Palermo, staging a suicide, or being deserted for work on a bonanza farm, but it did come to an abrupt end when Leopold committed suicide as a captive during the First World War.

The Baroness fashioned a wedding ring from a rusty hoop of metal she found on the road. It became Enduring Ornament (1913), one of her first and most significant artworks. It marked a turning point in art history: the invention of the readymade.

Freytag-Loringhoven moulded the title of The Baroness to fit her avant-garde persona. Aristocratic and Germanic-sounding, it was an ideal moniker to mark her out from the American crowd, defying the norms of New York’s bourgeoisie. She wore postage stamps on her cheeks instead of rouge, tin cans and spoons for clothes, and sometimes hung a birdcage round her neck (complete with a live canary). She was a living artwork; the Dadaist Baroness Elsa, the name she made for herself.

After visiting her studio on 14th Street, painter George Biddle wrote it was “reeking with strange relics” including “automobile tires, gilded vegetables, a dozen starved dogs, celluloid paintings, ash cans, every conceivable horror, which to her tortured yet highly sensitised perception, became objects of formal beauty.”

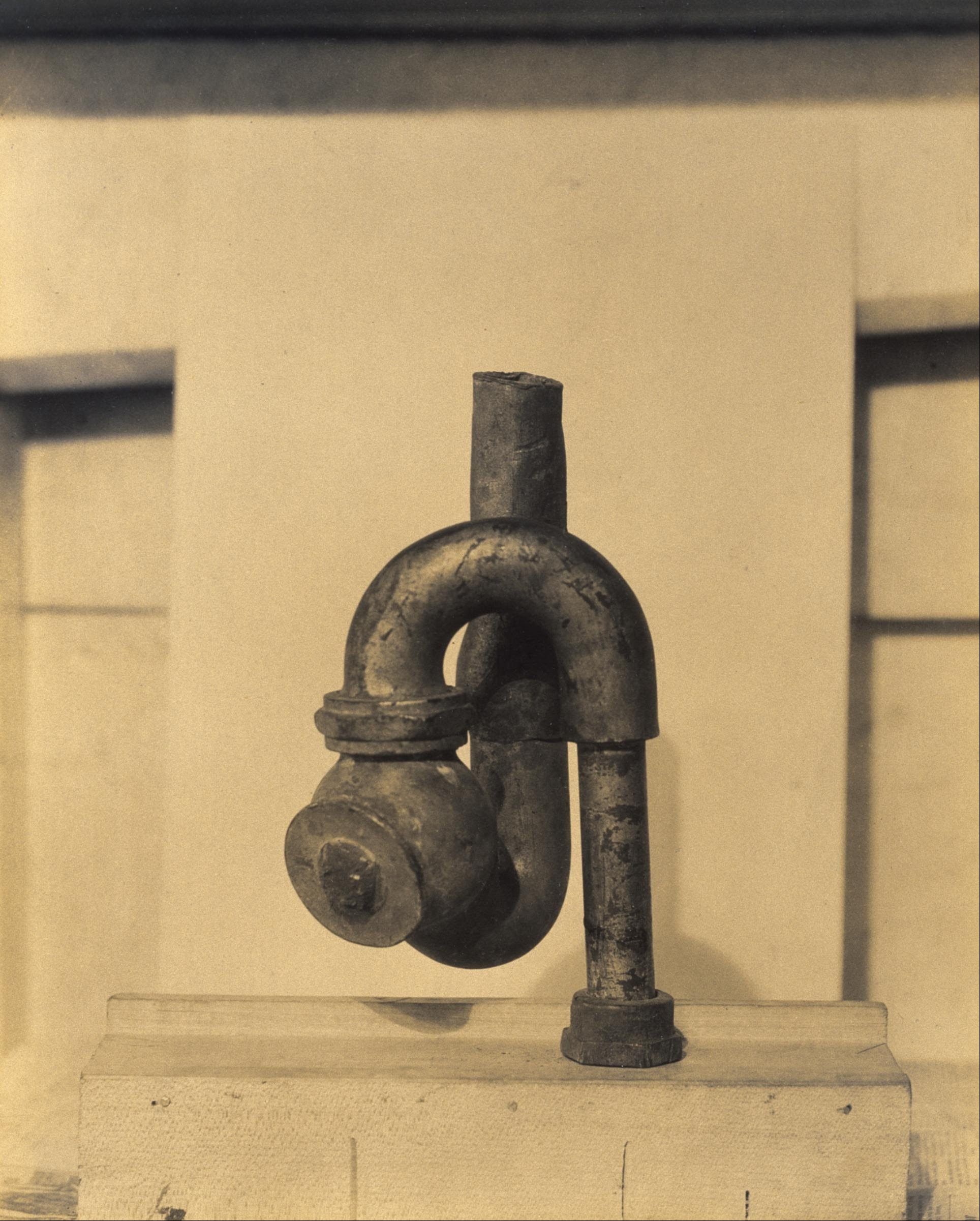

But The Baroness’ sculptures were more than banal objects, they were truly radical interventions. Pulled directly from daily life, transforming everyday matter into art, they implied art could be anything, if subject to the invigorating power and perception of the “tortured yet highly sensitised” artist. In her hands, a tiny wooden shard stuck on wire became Cathedral (1918); a twisted and phallic piece of plumbing is entitled simply GOD (1917).

And yet, despite her eccentric and iconoclastic creations, her status as ‘the Artist’ was often insecure; her “objects of formal beauty” dismissed as absurd detritus, or, worse still, misattributed. Even GOD (her most famous readymade sculpture) was long misattributed to Modernist painter Morton Livingston Schamberg, who had photographed it.

Over the last century The Baroness’s name, artwork, and extravagant proto-punk persona have all been somewhat forgotten. In comparison to the iconic, household names of Dada such as Jean Arp and Marcel Duchamp), Baroness Elsa is a somewhat shadowy figure, often an addendum to the official, canonical history of the Dada period and movement. Only a handful of her readymades survive, and her most-lasting body of work (her poetry) was not collected into a volume until 2011.

“She wore postage stamps on her cheeks instead of rouge, tin cans and spoons for clothes, and sometimes hung a birdcage round her neck”

Her influence is perhaps best seen in her artistic descendants, including those featured in a new exhibition at London’s Mimosa House which seeks to bring her legacy out of the shadows. The show, which includes a number of Baroness Elsa’s original writings and works alongside other artists’ new creations, revels in the grotesque, provocative, eccentric, and anarchic elements of her practice.

Inspired by the Baroness’s wood-fragment Cathedral, Birmingham-based Linda Stupart has built a structure fashioned from bark, branches, and “the skins of trees”. The sculpture towers in the space, reaching up to the skylight, giving the impression that it is growing out from the gallery’s walls. Like The Baroness, Stupart found the materials for this artwork (the ‘skins’ of this ‘readymade’) while out walking (though Stupart swapped the streets of New York for the banks of the River Cole in the Midlands).

Stupart suggests that much of the power of the Baroness’s artwork lies in these acts of recovery and reappropriation, noting how they break down conventional boundaries between inside and outside. “In a way these early readymades are always abject,” Stupart says, “bringing something in from outside that shouldn’t be there, like dirt on a shoe.”

The Baroness’s work anticipates the more explicitly abject, or shock art of the late twentieth century and beyond. Is her phallic, plumbing fixture GOD (1913) not an ancestor of Andres Serrano’s controversial Piss Christ (1987)? Is her studio “reeking with strange relics” not a perfect counterpart to Tracey Emin’s bed, her unmade readymade?

“Freytag-Loringhoven moulded the title of The Baroness to fit her avant-garde persona”

British artist Sadie Murdoch also ties the enduring appeal of the Baroness to a sense of raucous play and rebelliousness. “The Baroness’s artworks and writing position the rebellious female body as polysemous and generative,” she says, “an unstable trigger for production.”

Murdoch makes her own re-articulations in Pass-Way Into Where-To (2021), reconfiguring photographs from Dada archives, and placing them alongside cut-up poems and Dada manifestos. The resulting images are hauntingly beautiful, ghostly and strange. In one, the Baroness’s body has been removed and replaced with a photograph of an overgrown woodland. Her performative, lunging pose is still visible, but she has been rendered invisible, forced out of her own life narrative and out of art’s history.

“The Baroness’ sculptures were more than banal objects, they were truly radical interventions…they implied art could be anything”

If she could be returned to the frame, what would she do, or say? Murdoch suggests her work remains relevant because it challenges what is seen to constitute ‘functionality’, instigating “new types of thought processes” and “playing havoc”.”

Perhaps it is the sense of ‘havoc’, of unrestrained experimentation and defiance, that makes Baroness Elsa’s work and life so appealing today. With international borders and gendered norms being increasingly policed, her boundary-breaking, anarchic spirit, devil-may-care attitude, and unapologetic rebelliousness should be galvanising.

- Left Sadie Murdoch, Here Crawls Moon - Out Of This Hole, 2022; right: In Zinc, 2022

Recovering her work and reputation could also provide a framework for a contemporary generation of marginalised artists. If The Baroness’s legacy is to be found anywhere, it is in the work of the likes of Penny Goring who, like Baroness Elsa, works from her home using modest materials (ballpoint pens, fabric, food dye). In Goring’s vicious little drawings there is instability, abjection and violence, but also play, wry humour, and an anti-authoritarian, DIY sensibility. There is an obvious desire to reframe and remake the world (the artist’s current ICA show is titled Penny World). To make new, more chaotic and more liberatory worlds.

Murdoch describes reading The Baroness’s poetry as “like falling down stairs made of feathers and meteorites.” For a figure bedecked in spoons, stamps and live birds, really, what more could anyone hope for?

is a writer and poet living in London