On the occasion of Cassandra Mayela Allen’s second solo show at Olympia in New York City this past summer, she and Natalia Lassalle-Morillo discuss the trajectories of displacement and the power of collaborative creation.

Cassandra Mayela Allen’s and Natalia Lassalle-Morillo’s practices, though spanning different disciplines, share an uncanny similarity at their core; both emerge from a desire to work with community and create spaces to collectively process grief.

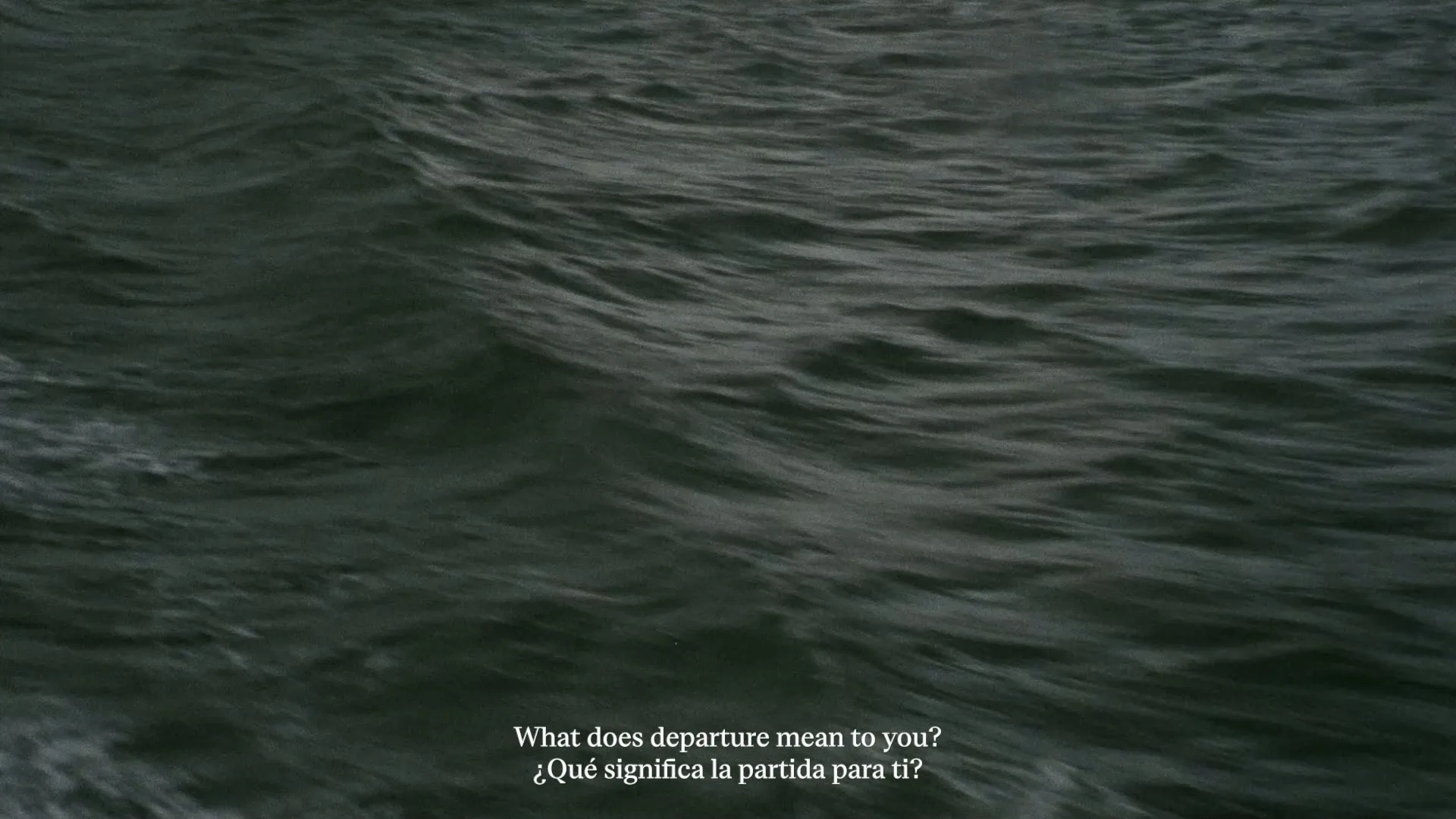

Lassalle-Morillo is an artist from Puerto Rico whose research-based practice reconstructs memory and history through a transdisciplinary and participatory approach. Her multi-channel film, En Parábola/Conversations on Tragedy (Part I) reassembled the myth of Antigone in collaboration with Puerto Ricans who reside in New York City.

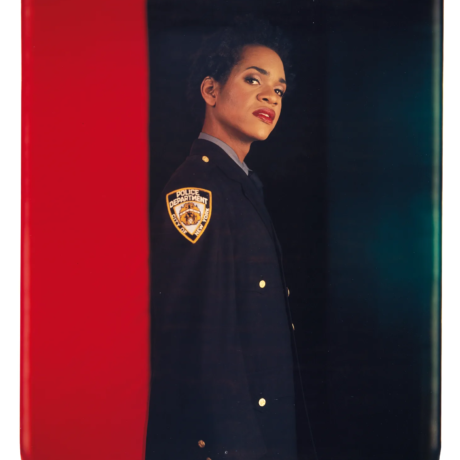

Mayela Allen’s practice revolves around site-specific works that convey her own experiences of forced migration, as well as the broader context of the Venezuelan migrant crisis. Her sculptural quilts and tapestries, created in collaboration with migrants in New York City, uncover the socio-economic conditions of diasporic communities in this city and reveal the enduring, often invisible structures that shape their lives throughout the United States.

Cassandra Mayela Allen: I’ve been wanting to continue this conversation since we met in D.C. back in 2022. I thought it would be a brief meeting, but I then realised we could never not get deep.

Natalia Lassalle-Morillo: It’s true—we quickly started making associations! There was this immediate familiarity between us, perhaps because we are both islanders, and because of the shared political and economic circumstances of our countries. Meeting you felt like a bálsamo, a balm, especially after spending so much time in a cold storage facility at the Smithsonian.

CMA: What were you researching during your time as an artist fellow?

NLM: I was investigating two collections: one comprising Indigenous objects from Puerto Rico, taken by Jesse Walter Fewkes—a Smithsonian anthropologist sent to Puerto Rico to collect Indigenous artifacts after the 1898 U.S. invasion—and a collection of Haitian Vodou objects, taken during the U.S. occupation of Haiti. I was interested in investigating how military interventions have shaped our relationship with these objects.

I also wanted to understand how ceremonial and ritual objects lived within these cold, morgue-like pods, removed from the people who care about them, believe in them, and who are meant to steward their histories. I’ve developed this research over the last two years in collaboration with Sofía Gallisá Muriente, an artist who was a fellow at the Smithsonian at the same time as me. We decided to look at the collection of Indigenous objects from Puerto Rico in dialogue with the Teodoro Vidal Collection of Puerto Rican History, and we’ve been reflecting on how our artistic work can facilitate their return to the people and places in Puerto Rico to whom they belong.

When we talk about diaspora, we often focus on people, on bodies that migrate. Encountering these collections led me to realise that objects, too, can be sentenced to a form of exile—especially when they have been extracted as part of colonial plunder. This takes me back to your work with Maps of Displacement [hereafter MOD]; you collected clothing donated to you by Venezuelan migrant participants, which you cut into fragments and wove into beautiful tapestries. Because these clothes once belonged to someone, they carry traces of their histories, their experiences, and their journey north. I’m curious to know about the process of developing MOD.

CMA: MOD started with observation. In 2019, after living in New York City for five years, I began noticing more and more Venezuelans in the city, like overhearing our accent in the subway, or seeing a street vendor selling arepas—things that never used to happen. Migrating is hard, and getting settled in New York is even harder, so I was curious as to how and why so many of us were increasingly arriving here. Unlike part of the Puerto Rican diaspora that came here directly to work in factories, for example, our migration has been kind of individual, almost by inertia.

At the same time, the lack of nuance in the news coverage of the Venezuelan crisis boiled my blood. Both the right-wing rhetoric and the American Left narrative fall short on addressing what we are actually going through. In response to this, I issued an open call in 2021, asking every Venezuelan I could reach to donate a garment that represented their migratory experience. I wanted to take back our narrative and share our stories, which remain open-ended.

NLM: I’m curious about the relationship between Venezuelans living in Venezuela and those in the diaspora. As an islander, I’ve witnessed the discrimination many folks in the archipelago direct at Nuyoricans for not speaking Spanish, but I also think this is deeply tied to class and race. There’s a lack of understanding of the causes that drove Puerto Ricans to migrate and the working and living conditions they faced in New York. In the process, many lost Spanish as their spoken tongue. Yet, as Puerto Ricans interacted with other migrant communities and African Americans, new ways of expressing Puerto Rican-ness emerged, like hip hop and salsa.

CMA: I grew up listening to The Noise, Olga Tañón, and Tego! When I moved to New York, I realized how much Venezuelans and Puerto Ricans share—not just culturally, but also in our Indigenous heritage. The Arawak and the Taíno peoples are one and the same.

There’s a lot of empathy and support between Venezuelans, but there’s also pain and division. Venezuela’s society was already fragmented by socio-political issues before this massive migration crisis, which has only amplified the “othering”—who is deemed worthy of leaving the country to start anew and represent Venezuela, and who isn’t, what do we want to be associated with, and what not. My intention with this body of work has always been healing this fracture. I learned through the process that many people do not want to heal, or aren’t ready to talk about their situation and their grief—and perhaps there are people who will. When I exhibited MOD in D.C., someone painted over a pro-Chávez cap that was woven into the piece. That anonymous gesture spoke volumes—we are not over it.

Something has happened though. Between the election this past July, its aftermath, and the performance of La Vinotinto, our national soccer team, these deep social divisions seem to have eased slightly. It’s hard to fully understand the meaning of these changes as they unfold in real time.

NLM: Definitely. Massive shifts of collective consciousness take time. Usually, the effects of what’s happening now won’t be fully realised for years. I also believe that hope is a rigorous practice. Witnessing a genocide and the rise of fascism around the world can make you want to give up. But I see hope as a daily commitment—something that requires intention and action.

We recently had a historical election in Puerto Rico: a pro-independence candidate received a third of the vote. His candidacy, along with the development of a new leftist political alliance, motivated so many people to get involved, to volunteer, to work the polls. For the first time in decades, we felt hope and understood how important it is for us citizens to implicate ourselves in the political process. Though the candidate didn’t win, this is part of a larger process—a series of rehearsals of our coming together to define what political liberation means for us, so as to not replicate the corrupt patterns of colonialism.

CMA: That’s what many in Venezuela felt with Maria Corina Machado this past election. There were so many people in the streets, protesting and protecting the vote despite the government’s corruption and oppression. This sense of hope and self-determination makes me think of Antigone’s posture against Creonte’s ruling—no hero is coming to save us. It’s up to all of us, collectively, to make a tangible change.

NLM: History is obsessed with creating individual heroic figures. Emma Suárez-Báez, one of my collaborators in En Parábola, re-wrote Antígona as someone who did not want to become a heroine. She was responding to a different kind of law, one ungoverned by mankind; for her, burying her brother against the laws of the state was not only an act of him a beautiful and dignified death, but also a way to reclaim agency over who and what deserves to be remembered. In Puerto Rico, the negligence of both the U.S. and Puerto Rican governments in the aftermath of Hurricane María triggered a collective reckoning—a reminder that el pueblo es quien salva al pueblo.

Returning to our conversation about diaspora, I do think the perception that Puerto Ricans in the archipelago have of the diaspora has changed, especially because of the mass exodus and the economic and political disaster that followed Hurricane María. Everyone now has a family member who has been displaced stateside or abroad, or has at some point considered leaving. Two generations from now, their children will, like Nina Rodríguez says in En Parábola, “be born in a place of feeling displaced.”

CMA: This was something that really resonated with me in your film. It makes me think about solastalgia—the distress caused by environmental change—from the perspective of inheriting your ancestors’ uprootedness and grief.

NLM: Do you remember when the “Avenue of Puerto Rico” sign at Graham Avenue in Williamsburg was taken down last summer? A couple of my friends who live in Puerto Rico wanted to understand the meaning behind this gesture; Puerto Rico has colonial and environmental ruin everywhere, reminding us of a history, that something was once there, regardless of whether we fully understand it. In New York, ruins are rapidly being replaced with luxury apartment buildings. That sign held meaning for Puerto Ricans amidst the attempts to eradicate traces of their histories in that neighbourhood.

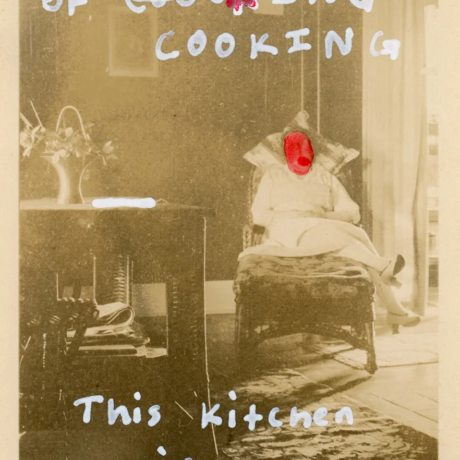

CMA: Yes! This city changes so aggressively. The first apartment I lived in is now a deli—there’s a beer fridge where my bed used to be. No trace that that it was ever a residential space. I began reflecting on this and documenting it years ago, before I ever thought about making quilts with the city’s imagery. Storefronts are very telling of the community in a neighbourhood; delis in Bushwick cater to Latin-Americans, while bodegas in Greenpoint showcase Polish products. As the city gentrifies, these businesses end up whitewashing their storefronts to appeal to new demographics. I’m making these quilts to remember these spaces because they represent the people—a curious departure from MOD, which uses people’s belongings to reflect on a place.

NLM: Your works are like a visual map. To an extent, the aesthetic decisions—the colour palette and the texture of the material—are defined by the clothing your collaborator donates. But this new body of work developed for Desahogo responds to the ecosystem of New York City, and to your experience as a migrant who finds a sense of familiarity in the bodega.

CMA: Bodegas are centres of multiculturality and community in New York; they came up with the arrival of immigrants and have become staples for the city’s diasporas. These spaces bind neighbourhoods together, and I believe they’re worth honouring.

NLM: How did you begin making quilts?

CMA: I had to take a break from the collaborative aspect of MOD to care for myself, both emotionally and physically, because my wrist couldn’t handle the intensity of handwork. I realised I was the channel for the work, but had no control regarding the aesthetics; I wanted to create art that gave me more creative agency.

NLM: Collaboration is a process of surrender and negotiation. There’s a letting go that happens when you work closely with others, a back-and-forth that transforms the initial idea. But there must be a balance between the parts of the process where you become a transmitter for others, and the parts when you closely observe everything you’ve gathered, in silence and solitude. Our projects are extremely intimate, both in how we work with our collaborators, and also in that the subject matter is closely tied to our realities. My work has often been in dialogue with the situation in Puerto Rico, and while I’m usually not visibly present as a subject, my grief and anger are present.

CMA: For sure. The inquiries I ask my collaborators are the ones I ask myself. In a sense, I’m trying to build a community so we don’t feel alone in this process. The tricky thing is balancing hard work and burnout, though I suppose we can only find it as we go. I struggled with it last year and had to step back, so I’ve been working mostly alone for the past year and a half. I find this very valuable when developing my work—allowing space for rituals, reflection and contemplation.

Words by Cassandra Mayela Allen