The Navajo (Diné) artist Melissa Cody is a fourth-generation weaver, creating her first weaving on a Navajo loom at five years old, titled Banded Blanket (1988). Using scraps of materials that had pooled around her mother’s loom, Cody created a spatial and rhythmic configuration of colours, each band dyed with muted organic pigments from the southwestern region of the Navajo Nation.

The blanket is the earliest work in the artist’s mid-career retrospective, Webbed Skies, at MoMA PS1 in New York, which primarily focuses on the last decade of Cody’s output. The exhibition opened under the title Céus Tramados at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo last year as part of the museum’s year-long curatorial focus Indigenous Stories—an exhibition series that examines the generational continuum of indigenous art practices through a contemporary lens.

Cody was born in 1983 in No Water Mesa, Arizona, a remote region in the Leupp chapter of the Navajo Nation, which covers 16 million acres across the states of Arizona, Utah and New Mexico. A descendant of a storied lineage of weavers, her mother and father each had thirteen and fifteen siblings, most of whom were based in the same area and taught to use the Navajo loom from childhood. Her three siblings were also taught to weave, and her grandmother—now in her nineties—still maintains a “highly experimental” studio practice, says the artist.

In No Water Mesa, each person had a role: some children worked cattle or tended sheep, others sheared the sheep in the springtime, and others cleaned the wool. All would help spin the wool and prepare the materials before older family members would begin the weaving process. Once the textile was almost done, younger family members learned how to weave by working on the finishing.

The No Water Mesa community is over forty-five miles from the nearest metropolitan area and still mostly operates without running water, electricity or plumbing. The tribal government was established in the 1920s, but the persisting lack of economic opportunities has prompted many Navajo—including the artist’s relatives—to seek a secondary income through the arts. Throughout her childhood, Cody’s family sold their textiles to trading posts, galleries in Sedona, and in indigenous art markets in California, New Mexico and throughout Arizona.

“Whereas I learned to weave with a more artistic-minded approach, my mother and other relatives learned by necessity—they had to clothe themselves and put food on the table,” Cody says. “Some people in the community were jewellers or silversmiths, while others wove baskets, created household items or did beadwork. In our house, we were weavers.”

Cody learned to weave on a traditional vertical Navajo loom, a mathematically complex and physically intensive weaving method that is entirely manipulated by hand. The dimension of each textile is predetermined, so there are “no shortcuts,” she explains. Each string pulled in the loom is compacted using small tools called combs. Unlike floor looms that are cut when the textile is completed, Navajo weavers weave until the end of the working system.

Alongside her siblings and cousins, Cody also entered her textiles in youth contests and sold her work. She enrolled at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 2002, keeping a loom in her dormroom to create large-scale and smaller works for exhibitions and art markets, which “put her through college,” she says. However, she opted out of coursework in textile and fibre arts to pursue degrees in museum studies and studio arts and broaden her approach to her practice.

“In the 2000s, I was getting a deeper internal understanding of who I was as a Navajo person and an indigenous woman who happens to be a fiber artist, and was thinking about where I wanted to situate myself in the art realm,” Cody says. “There weren’t many young weavers excelling in the field, or even many who had the foundation of knowing how to weave. I wanted to bring weaving back to the people and make it appealing and exciting again.”

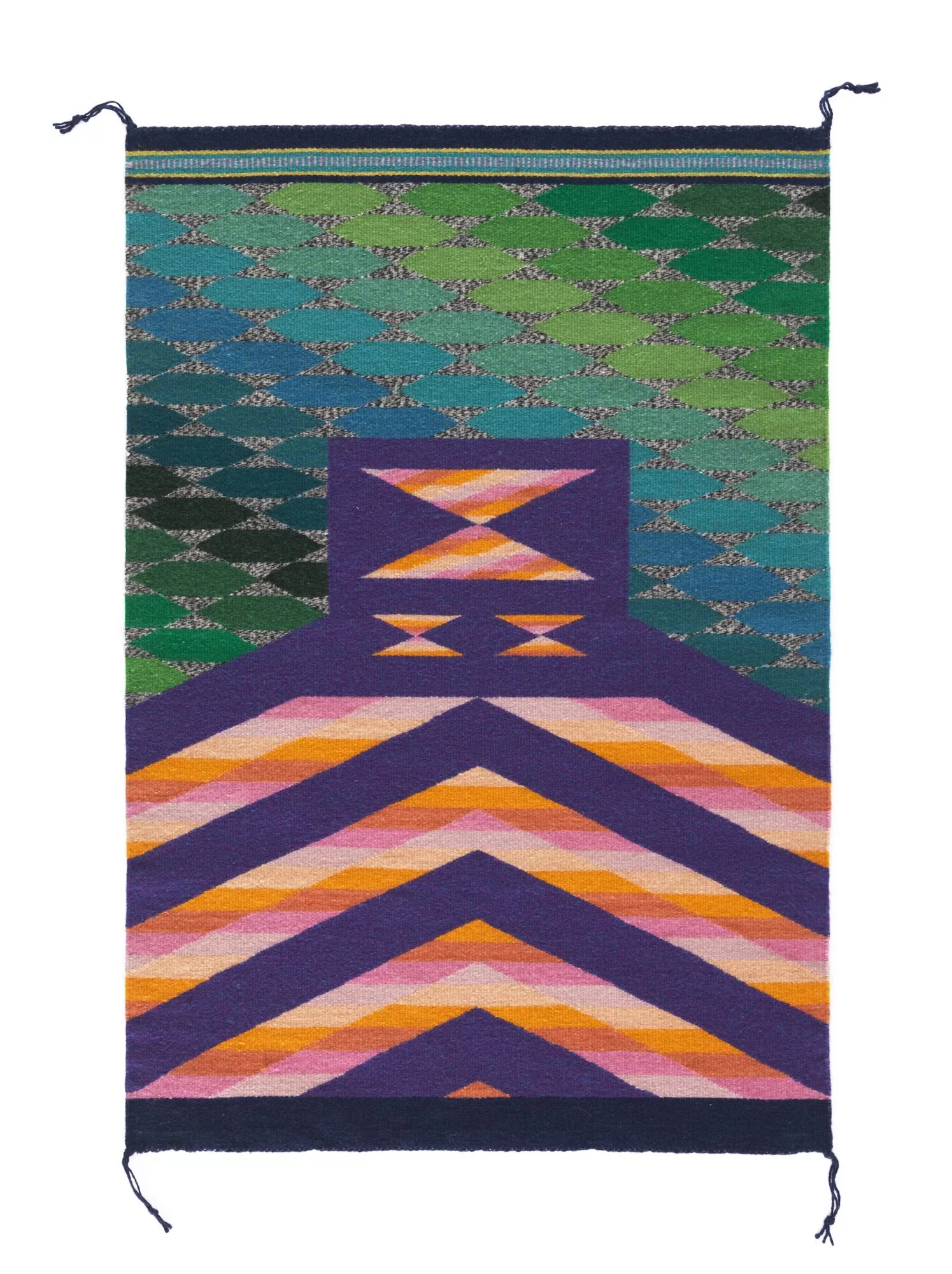

After her graduation, she returned to Arizona and re-shifted her attention to her studio practice, focusing on advancing the tradition of Navajo Germantown weaving. Seeking to honour but reframe the tradition, she began using Germantown wool, a versatile and colourful yarn that she had been introduced to as an adolescent, to create works that mixed traditional elements with modern-day digital automation and text, many examples of which feature in the New York exhibition like in the recently-completed work Into the Depths, She Rappels (2023).

“I was immediately drawn to Germantown wool just in terms of the aesthetics because the palette is so bright and vibrant,” Cody says. “But it spoke to me much more when I began researching Germantown revival.”

Germantown wool was the textile used in blankets that the American government provided as rations during the Long Walk era, a period in the mid-1800s when more than 10,000 Navajo were forcibly expelled from their territories and marched to the Bosque Redondo Reservation at Fort Sumner in present-day New Mexico. Because the Navajo had no raw materials to work with, weavers repurposed the blankets (which had been milled in Germantown, Pennsylvania) by unravelling and reweaving them.

“The Long Walk era was a dark point in Navajo history—we were on the verge of losing not just our people but our arts, religious freedom and culture,” Cody says. “The main goal was to exterminate us and, in doing that, they targeted our sustenance, which was the sheep; we eat mutton and that’s what we use for the raw material to weave our textiles.”

Cody’s tapestries masterfully incorporate Navajo mythology and symbolism. One motif Cody has sought to reclaim through her work is the Whirling Log—a symbol visible in the work Navajo Whirling Log (2019). A Navajo symbol representing good luck and protection, the Whirling Log has been recorded in Navajo pictographs and petroglyphs dating back 6,000 years but is sometimes confused for a Nazi swastika.

Her works incorporating the motif generated “welcomed conversations” and “gave others this foundational platform to push other boundaries within their own work,” Cody says. “It wasn’t done solely out of shock value, but as a means to harness ideas that had been suppressed, and to heal and process intergenerational trauma through open dialogue.”

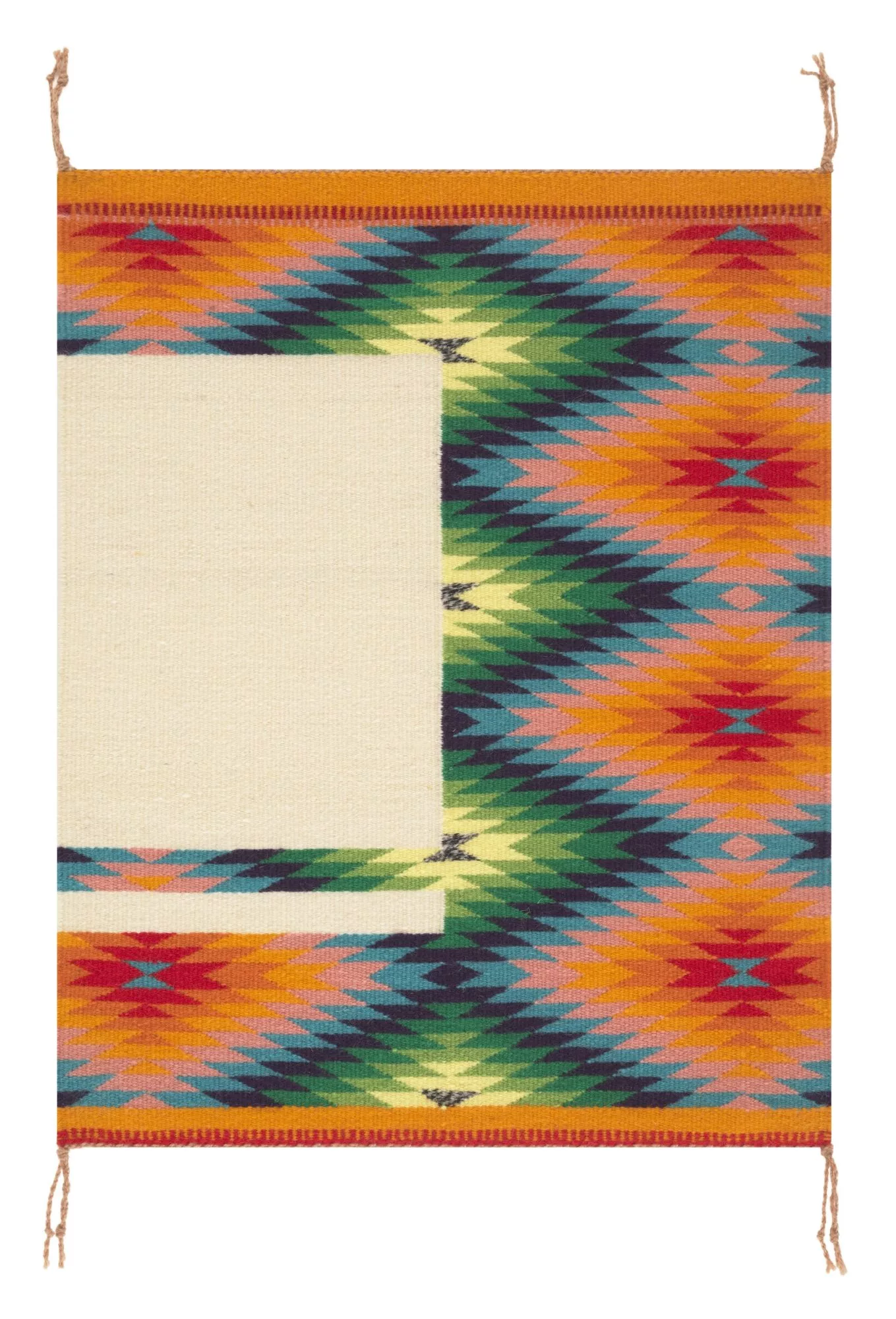

Another recurring motif is the serrated diamond, a so-called “eye dazzler” pattern visible in works like Spider Woman Greets the Dawn (2013) and Pocketful of Rainbows (2019). “It’s technically versatile and exudes pulses of energy, which I think is the energy I’ve tried to harness within my work,” Cody says. “I want the textile to transport the viewer into whatever world I’m weaving within—into an interdimensional plane.”

Most of the patterns reference the landscape and nature. Although the patterns could appear similar to the lesser primed, each weaver has a specific tension and hand. “Some don’t weave diagonal lines at all, others just blocks and squares,” Cody says. “In my textiles, I have clean edges where one design stops and another pattern begins, and usually the two have a distinct tensioning. My entire career has been about perfecting the tension to create these flawless breaks and patterns.”

She maintains that straight, flat lines are the most challenging to create.

In preparation for her current retrospective, which has been organised in collaboration with Isabella Rjeille, curator at MASP, Ruba Katrib, the curator and director of curatorial affairs at MoMA PS1, Cody reflected on the development of her practice and her rise as an artist. Over the last two years, her work was featured in several group exhibitions, notably at the Hammer Museum’s Made in LA 2023: Acts of Living and at the National Gallery of Art in 2023 in The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans, an exhibition curated by the artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation).

“It’s exciting because I’ve stepped out of the umbrella of the Native American art scene and moved into a contemporary art world,” Cody says. “The foundation of everything I do is paying respect to the weavers who came before me. But people need to understand that Native American art doesn’t have to fall within tradition; traditions are fluid and change and evolve.”

Cody typically spends between eight and six hours per day in her studio in Long Beach, California, where she has been based since 2013. Her large-scale pieces, which span up to nine feet in height, take around six months of consistent work; smaller pieces can take around one or two months. She works without assistants and with a vertical loom that, although larger, operates the same way as the loom she first wove when she was a child. She will soon teach her own three-year-old daughter to weave. Her daughter accompanies her in the studio every day, playing nearby with her toys or with Cody’s materials.

“Being a new parent has made me hyper-aware of being a steward of this information and how I want to pass on this information to the next generation—not just an interest in the arts but specifically in textile work,” Cody says. “I especially want my children to feel comfortable in this space and have weaving be as readily accessible for them as it was for me. My mother made sure that we learned but never forced it upon us; having a love for it was a natural transition.”

Written by Gabriella Angeleti

Melissa Cody: Webbed Skies, MoMA PS1, New York, on view until September 2, 2024

find out more