Imagine that you are a child. You are blindfolded, though bright light peeps in above and below the black-panorama band. A stick is in your hands and someone is spinning you, not too quickly but fast enough that you become discombobulated. Suddenly the hands withdraw. A raucous din erupts, friends screaming with frenzied anticipation. You are dizzily thrashing at the air, aiming for that bright yellow, papier-mâché lion hanging from the tree. The piñata. Then suddenly: Bam! Shrieks of delight erupt and as you pull off the blindfold you see the lion decapitated, lying eviscerated in a pool of sweets, its sugary blood spilled everywhere.

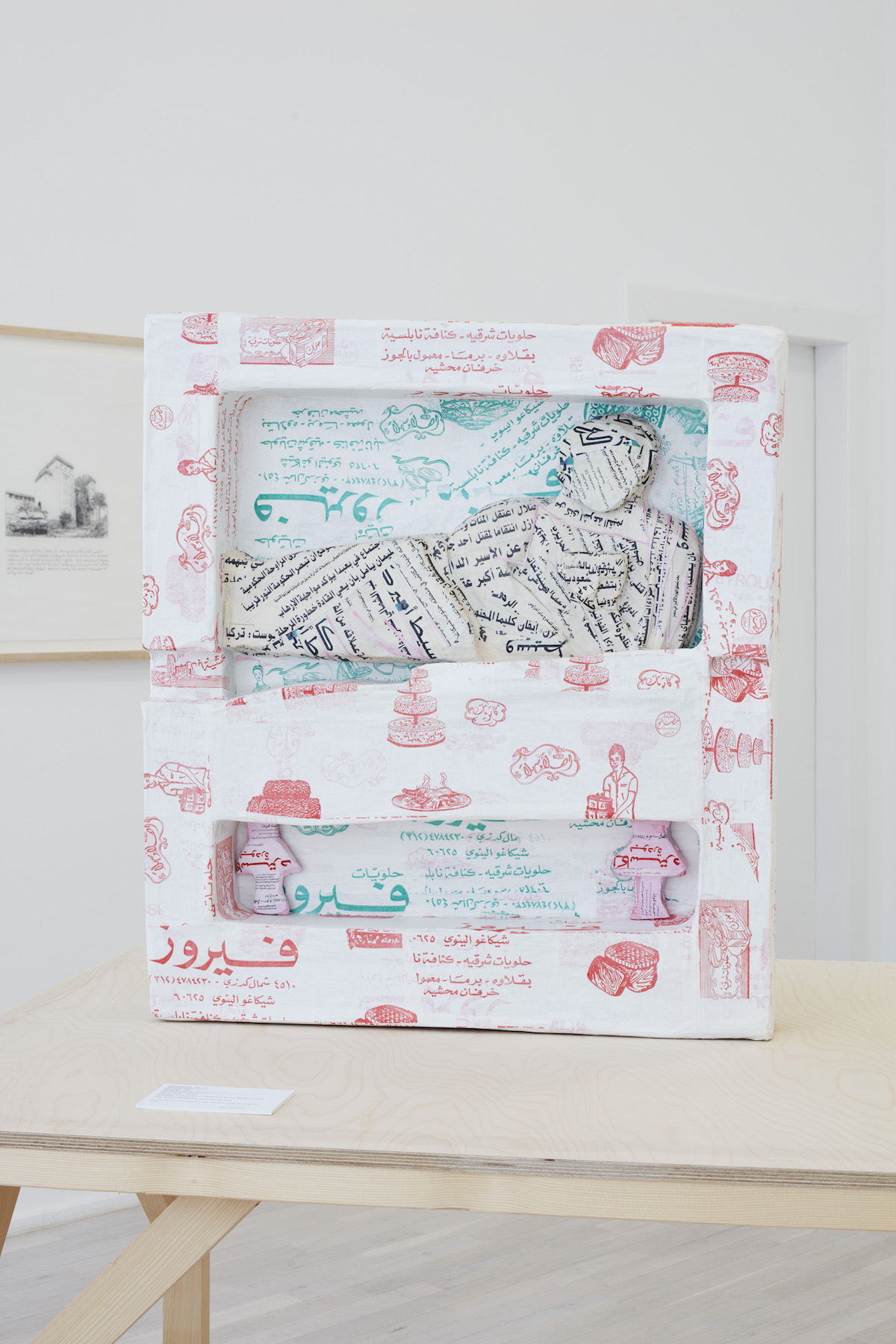

Now imagine that the lion is actually made of terracotta and lies surrounded by its own powdery dust, clay pulverized, as it did in Baghdad’s National Museum of Iraq. It dates from 18,000 BCE, one of two Babylonian lions found at the gate of the Dagan temple in Tell Harmal (ancient Shaduppum). That make-believe mane of rolled-up newspaper emblazoned with Arabic scripture is actually a mass of terracotta volutes; its body of acid yellow and aqua blue packaging is a smooth earthen surface; claws of silver foil are finely sculpted clay, as are the teeth projecting from the lion’s dismembered roar.

American artist Michael Rakowitz’s 2016 Berlin-based exhibition at Barbara Wein Galerie, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, paid homage to this lion. His papier-mâché manifestation sat majestically amid thirty-seven other artefacts made from cardboard, Middle Eastern packaging and newspaper. The eponymous body of work (2007–ongoing) responds to the sociocultural history that followed the 2003 invasion of Iraq when over 15,000 objects were decimated, displaced or disappeared from the Baghdad museum. Rakowitz has described how he “looked back at actual objects, marked the things lost”, in an attempt to bring new life to archaeological pieces that we may never see again.

Displayed upon two utilitarian wooden trestle tables, Rakowitz recreated objects down to their minutiae: tiny jars that were originally inlaid with mosaics; a relief of a reclining woman; Poseidon standing tall, armless but proud; the seated consort of Hercules; a male figure, eyes initially set with pearl, pupils of lapis lazuli; grins; stags; falcon-headed sphinxes; winged deities. The list goes on.

“By imbuing his recreations with a sense of craft, playfulness and joy, he allows us to acknowledge the difficult stories attached to the original objects and celebrate them”

Next to each, a taxonomic label delineated the object’s basic information (original material, date) and its current status—in the case of the lion: “In museum, head destroyed during museum looting”, while others read “stolen” or “unknown”. Where you might usually expect to see an interpretive text describing the object, Rakowitz had instead quoted professionals ranging from politicians to archaeologists, museologists, journalists and academics, all of whom have expressed their views on iconoclasm with varying degrees of seriousness—some pithy, some passionate, some flippant:

“Let me say one other thing. The images you are seeing on television you are seeing over, and over, and over, and it’s the same picture of some person walking out of some building with a vase, and you see it twenty times, and you think, ‘My goodness, were there that many vases?’ (Laughter.) Is it possible that there were that many vases in the whole country?”—Donald Rumsfeld.

“Our archaeological heritage is a non-renewable resource. When a part is destroyed that part is lost forever”—Usam Ghaidan and Anna Paolini.

“Some appear to have been professional, acting in concert with international dealers and even with resident diplomats”—William R. Polk.

As a viewer, one pieced together these fragments. Their clear didacticism opened a portal into the complex narrative of iconoclasm, which also led me to question how we value material culture (our own and that of others) in a digital age where matter is increasingly dematerialized.

Alongside destroying cultural heritage, ISIS has scaled up and professionalized the trade of antiques within Iraq and Syria, creating a food chain of supply and demand and profiting through taxation. Small but constant transactions drive this business, and it has been reported that $300 million worth of antiquities have flooded the market as a result of ISIS’s dealings.

Rakowitz’s objects are very clearly not attempting to be the originals or, indeed, to usurp them. These are not simulacra—certainly not in the sense that Baudrillard explored in his Simulacra and Simulations, wherein the simulacrum claims its own independent truth, surpassing the original’s signification: “It is the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal.” Rakowitz’s forms honour the memory of what once was. With their bright colours, they are reminiscent of children’s figurines, lively objects designed for bashing—the piñatas that they recall are even intended for annihilation, and their existence depends on their destruction. Therefore, these forms inflect the destiny of the original ill-fated objects. By imbuing his recreations with a sense of craft, playfulness and joy, he allows us to acknowledge the difficult stories attached to the original objects and celebrate them, rather than relegating them to the status of ghosts of the dead.

- Excavation Extraction

- New Babylon, from The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, 2007–ongoing

As the grandchild of a Jewish-Iraqi family who fled to the United States in 1946, Rakowitz’s practice often explores his ancestral country, from Enemy Kitchen (2006–ongoing), where Iraq War veterans dished up Baghdadi recipes from a food truck, to Spoils (2011), where he served dinner on Saddam Hussein’s actual dinner plates, which he sourced on eBay from an American soldier in Iraq. The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist tapped into an expanded field of current affairs, where iconoclasm stands as an urgent issue.

It is precisely the Western interest in culture and antiquities that gives the agenda of PR-savvy ISIS its political agency; its iconoclasm is a complicated phenomenon, with religious, political and economic motives. It would be a gross simplification to see these as senseless expressions of violence and abuse carried out by brainwashed militants; these are calculated acts that are broadcast to the world to spread a message of extremism and invoke fear.

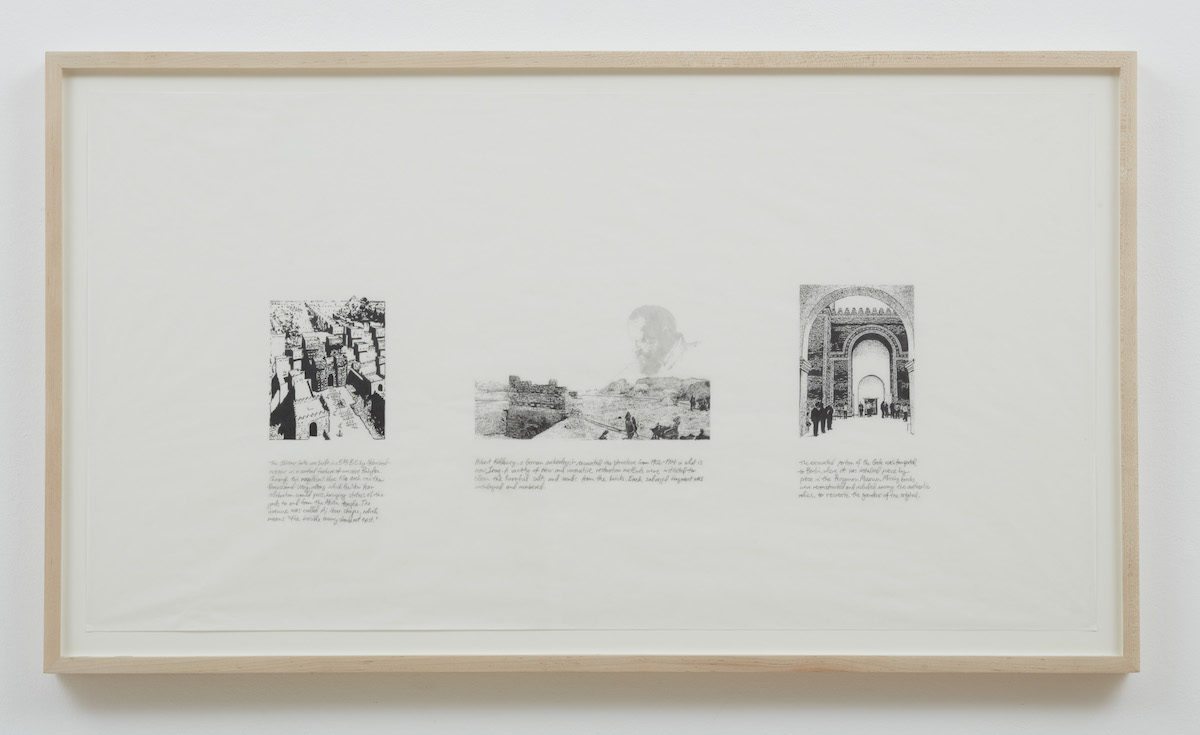

Of course, Rakowitz’s project does not solely implicate ISIS; it also acknowledges the colonial backstory of iconoclasm. His comic-strip-like pencil drawing Excavation Extraction (Recovered, Missing, Stolen Series) (2007)—part of a wider series—depicts the Ishtar Gate of 575 BCE. The drawing describes the magnificent blue-tiled arch’s history, excavated between 1902 and 1914 by German archaeologist Robert Koldewey and transported to Berlin, where it still stands today in the Pergamon—just over three kilometres from the site of Rakowitz’s own exhibition. Another illustration from the same series, New Babylon (2007), describes a US helipad built in Iraq by the site of the Ishtar Gate ruins; the landing spot remains there today despite archaeologists’ complaints of damage. Even the exhibition’s title, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, translates directly from the phrase “Aj-iburshapu”, which was the name of the ancient Babylonian street passing through the Ishtar Gate. It reminds us that Imperialist agendas continue today, with the return of this ancient monument to its homeland being disputed by the German government, over-riding Iraq’s right to its cultural heritage.

“His kitsch replicas never intend to provide a viable alternative to the value and status of real antiquities, though with today’s contemporary art market being a billion-dollar industry, stranger things have happened”

Rakowitz’s objects have an ontology that exists somewhere between art object and reconstructed artefact. Being sold through the commercial gallery system, they do enter into the marketplace, with the artist hoping that they carry the essence of the original and have “maybe created an uncomfortable ghost in an art collector’s collection”. With the West’s demand for antiquities fuelling the black-market trade, Rakowitz satirically acknowledges the market’s role in enabling the pillage of cultural history—his kitsch replicas never intend to provide a viable alternative to the value and status of real antiquities, though with today’s contemporary art market being a billion-dollar industry, stranger things have happened.

So, to what degree can art ever really offer solutions to sociopolitical problems beyond critical inquiry? In the run-up to Documenta 14, curator Adam Szymczyk stated that amid “the continuing military and political involvement of the Western powers and Russia in Syria… it is not clear what contemporary art can do in order to change the increasingly indefensible and clearly unsustainable state of things”. For Rakowitz, it is about trying “to make an unlikely thing happen, and the impossible becomes possible. It’s art because it’s impossible for this to exist in the world.” By reincarnating these artefacts as contemporary art objects, they have a revised ontology that can sustain their existence and draw attention to the unsustainable state of things. In a world increasingly obsessed with dematerialization and digital avatar existence, our existential need for the physical evidence of who we are and who we once were continues to fuel our insatiable relationship to objects—and our fear of their disappearance and death.

Images courtesy Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin. Photos: Nick Ash

Michael Rakowitz: The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist

The Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square

Photo by Caroline Teo

VISIT WEBSITE