“I like my art to be on the floor, not on the wall,” says Swiss photographer and artist Michel Comte. “If you look at glaciers, that is how they are.” The exhibition space in Milan’s Triennale museum is dark, apart from a sort of blue polar winter light emanating from one of the installations. Next to each other on the floor are photographs of glaciers from above, which the artist flew over in helicopters or hang gliders. Meanwhile, the MAXXI in Rome has a polar opposite equivalent. He shows me a picture from his Instagram feed of a white room, in which gallery goers are instructed to remove their shoes so as to cause no sound, as in untouched landscapes, and so as not to tarnish the room’s “uninterrupted light and uninterrupted space”, as he says. His grandfather Alfred Comte, one of the first aviators to cross the Alps, took the first aerial photos of them over a hundred years ago. “They were taken in summer,” says Michel, “but everything was white. Today you find, in summer, in Switzerland, everything is black with some silver caps.”

Comte is famous primarily for his fashion photography. When he was twenty-five he was collared by Karl Lagerfeld, and since then has photographed subjects from Iggy Pop and Ray Charles to Jeremy Irons, Scarlett Johansson and the Dalai Lama (who he counts as a personal friend). He shot Miles Davis and the picture became an album cover. “I never planned to be a photographer,” says Comte, who before that restored works of modern art. “That’s how I started. Maybe I’m going back to where I came from, and what I really enjoy doing.” Indeed, his sprawling project Black Light, White Light, began thirty-seven years ago and has taken him from the Alps to the Himalayas to Svalbard. He not only documents climate change’s effects—as with a video installation projected onto the outside of the MAXXI capturing the violent, surprisingly deafening rush of glacial melt—but tries to slow those effects as a piece of land art. He covers glaciers in British Columbia with protective space blankets during the summer months. Next, he plans to drill cooling tubes into them.

“If you go to where it is happening, it is frightening. If you go to an ice cap, the amount of water they lose creates huge waterfalls. Last August, Spitsbergen in Norway was like Niagara. The ice cap there is receding 30cm a day.” At the back of the room here in Milan is a silver mass of foil, referencing but not replicating his covered glaciers. The amount of ice this blanket could cover would, he tells me, make the floor collapse. “We can stop the melting for three months and then when the snow comes we can start the rebuilding, but the problem is wind. It takes a lot of maintenance and manpower, and even then you cannot stop it, only slow it down. Stephen Hawking has said that if Trump makes his full presidency, the acceleration of the melting process will be 37%. Even if we change our ways, we cannot completely stop it, only slow it down.”

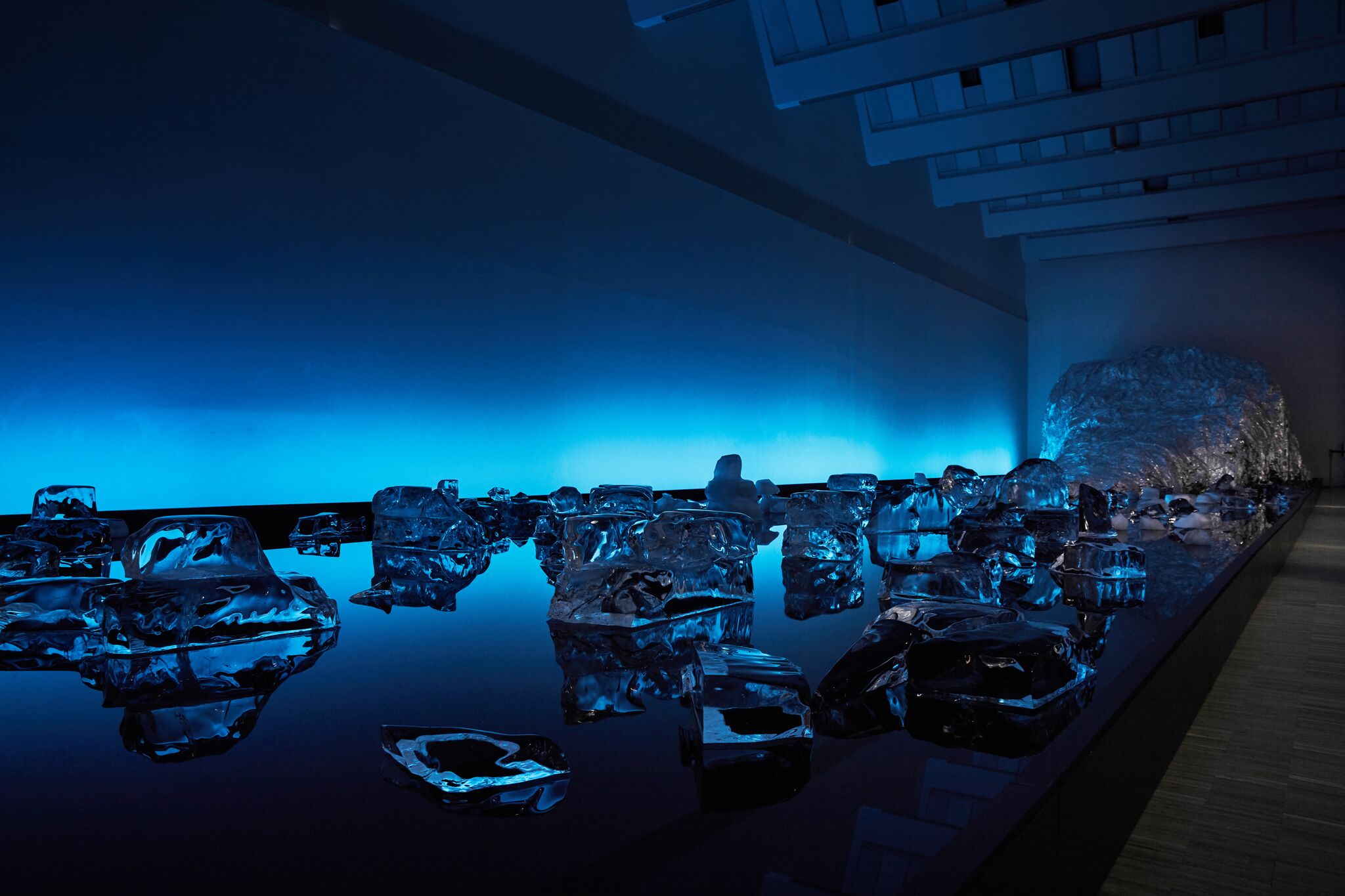

In front of the space blanket mountain there is a long installation with what appears to be a reflective floor, lit up by auroral blue. What appear to be glass sculptures, gem-like in dark spaces, are ice blocks Comte himself has chipped into shape. The ground is water, and you can hear the dripping. “Every night we vacuum a little bit out, so it doesn’t overflow.” New ice is brought in every week. “But it’s most powerful when the very last ones almost disappear,” he says.

“I think contemporary art has its own politics. We, like politicians, have our own attempts to make a change.”

If the ice looks like mimetic glass sculpture, there are also glass sculptures that mimic glaciers, containing bits of real glacier. Collected pieces of stone, sand and other materials—copper, iron, pyrite and gold—have been mixed and poured into mountain-shaped moulds, producing organic glass sculptures that look like marble or quartz. He leans on them as he talks. “People can touch them,” he says. “People should touch them.” I do. They’re soft around their ridges.

I ask him how long he has had an appreciation of the natural world. He says “always” repeatedly. But what is his earliest memory that resulted in that love, and also perhaps ignited a response on such a grand, forty-year scale? “I was about seven and had been doing a lot of skiing. A helicopter dropped me and my teacher off at the Breithorn mountain range and we skied all the way to the south of Switzerland. At this core of deep snow it was very, very dry. It was like you were like on the moon you know, and there’s not one sound. Only ‘tschhh, tschhh’. We sat and and opened our thermos flasks with hot tea inside and I thought this is not possible, this world is just so incredibly beautiful. I think that triggered a lot.”

“If you go to where it is happening, it is frightening. If you go to an ice cap, the amount of water they lose creates huge waterfalls.”

It’s a lovely thought, made more lovely by the fact we’ve all had a similar childhood memory of snow’s purity, and made sad by the fact that children of today and tomorrow might have less access to a similar experience. But what can really we do, as individuals, besides mourn and reminisce? Comte has said that he wants this exhibition to show we should have a cleaner and greener future. But how can visual artists actually contribute to stabilizing that rate of global warming or ice caps melting? “I think contemporary art has its own politics. We, like politicians, have our own attempts to make a change. All we can do is use the tools we have to show in simple or abstract ways how change is happening: our own specific means of communication. I think that’s the great power. Just like you: you have your pen. Or your machines.” He gestures to my phone and dictaphone, one of which I am reading questions from. The other is sat between us on the platform for a piece of onyx chosen, after a long search, because it looks like a mountain. He talks about the misuse of such power. “You put on Fox News, for instance: that’s terrible. But then you read two lines of Salinger, or you look at Yves Klein or Canaletto, or you look in the eye of a child—you are touched. Whether it’s with your pen, your phone, or with sound; if we use this in a good way, then, I think, we can make a difference.”

I bring up the fact he has in the past photographed Donald Trump: the very person on whom he laid responsibility for the current rate of glacial melt. Doesn’t using the power of his platform, his means of communication, involve drawing a line as to who he shoots? Comte laughs in the spritely, high pitched way he has when something interests him. “No. I would go, and I would read [Trump] the rights. I played racquetball with George W Bush. I asked the same questions of him as I would have asked of you. I have no qualms about that, and I think people respect me for this. I never draw a line between people. I treat them with the respect they deserve, but no more than that.” So he would photograph Trump now? “I’d take the picture. But I’d use the opportunity to tell him what I believe and to resign.”