A confession: I was introduced to Milton Avery’s work on Instagram. I saw him first on a scroll, my eyes caught on the fields of vivid colour, the swerve of a cream thigh, the triangular shadow of a crooked elbow. Not a traditional introduction to a master of fine arts admittedly, but an introduction nonetheless.

Born in New York in 1885, Avery’s world is Tetris-like; contours give way to clear borders. It is all colour and clear demarcations, the arch of a raised kneecap, a curved back: the forms of life split into shapes. Filled with simple compositions of domestic scenes, these paintings lend themselves to the square-blocked online visual world we curate and consume daily. Striking shapes and clashing colours catch the eye—his subjects stick in a scrolling world: swimmers relax on a Maine beach; a woman curls round a good book; people crowd about a table in convivial conversation. The work springs from life. Its allure? Honesty.

Young Couple (Husband and Wife), 1963

Rothko famously noted that Avery’s repertoire was “his living room, Central Park, his wife Sally, his daughter March”, his paintings peopled with an “unheroic cast”. Yet it is precisely these “normal people” and the domestic sphere they frequent that elevate and celebrate the everyday. In a world where, for many, publicly documenting daily routines has become not only “normal” but a necessity, it’s hardly surprising that art which echoes the off-the-cuff Instagram shot of a cluttered desk, a bedroom view, a morning coffee or an evening with friends has come to resonate with an online audience. The images we make of our own lives are those concerned with the tiny windows of our day-to-day, which are at once for our own viewing pleasure and that of anyone else who cares to look.

“It’s hardly surprising that art which echoes the off-the-cuff Instagram shot has come to resonate with an online audience”

Avery’s paintings remind me of Pierre Bonnard, another artist once ridiculed for his simplistic scenes. Like Bonnard, he draws his subjects from his own life, from the world of “normal people”. As with Bonnard, there is irony to be found in the fact that his works appeal to so many because they remain so specific to individual experience. In Bonnard’s Coffee (1915) a woman in a bright yellow jumper leans on a chequered tablecloth as she drinks a small espresso: the composition could be that of myriad Instagram posts.

A cup of coffee can be part of a carefully composed composition, but it’s also just a facet of everyday life. It can present something unique: our own mug; our own tablecloth; our own battered paperback. Yet it also belongs to the cast of human experience that reminds us of our own emulative tendencies. Something so easily reproduced, something so attainable, so normal, marks us out as entirely human: just another person who likes to spend a Saturday morning reading a good book; just another person who likes coffee. So what makes Bonnard’s coffee cup and its owner different? We’re shown them through Bonnard’s perspective; for a moment we’re allowed to see with another’s eyes.

Reassessing the “ordinary” has always had a place in art. Just think how Marcel Duchamp shocked the public back in 1917 with his infamous Fountain: perspective is key. Ask a room of students to capture a still life from the same objects and the results will present you with the conundrum of human experience. We all see differently. What we take from the things life throws at us remains distinctly individual. Being human is a lonely business; we never see the world from any other perspective but our own. We’re stuck with our own eyes, but art counters that.

In the current political climate, where hundreds feel ostracized and misunderstood, a clamour of voices cry for a unified national identity of an undefined “normal”. Art’s ability to evoke empathy and encourage alternative perspectives, to show the multifaceted contours of “normal” experience, feels more important than ever. Avery’s popularity online in social media posts highlights an intriguing trend of “normal” people currently swirling in the cultural zeitgeist. One only has to think of the “Normal” or “Ordinary” people in the recent novels of Sally Rooney or Diana Evans, where both authors interrogate the very terms of their titles.

A paradox. People long to be normal and yet despise normality. It’s a constant tug and pull. There’s a necessary allure to fitting in with the pack, but this desire is almost always at odds with establishing a sense of self. Success in algorithms supposedly comes from the familiar; any social media expert will tell you that. Yet while it’s true that people gravitate towards comfortable content presenting and reflecting their own views and experience, there’s a reason certain people come to stand out. Success, we are told, doesn’t come from normal. In fact, the rise of “basic” as an insult hints at the ways in which “normal” remains a conflicted term—a shorthand for shame. To like things that are obvious, normal or basic is somehow at odds with an interesting and individual interior and exterior life. Yet it’s undeniable that we all share certain “basic” elements of life. “Normal” things unite us all.

“Art’s ability to evoke empathy and to show the multifaceted contours of ‘normal’ experience, feels more important than ever”

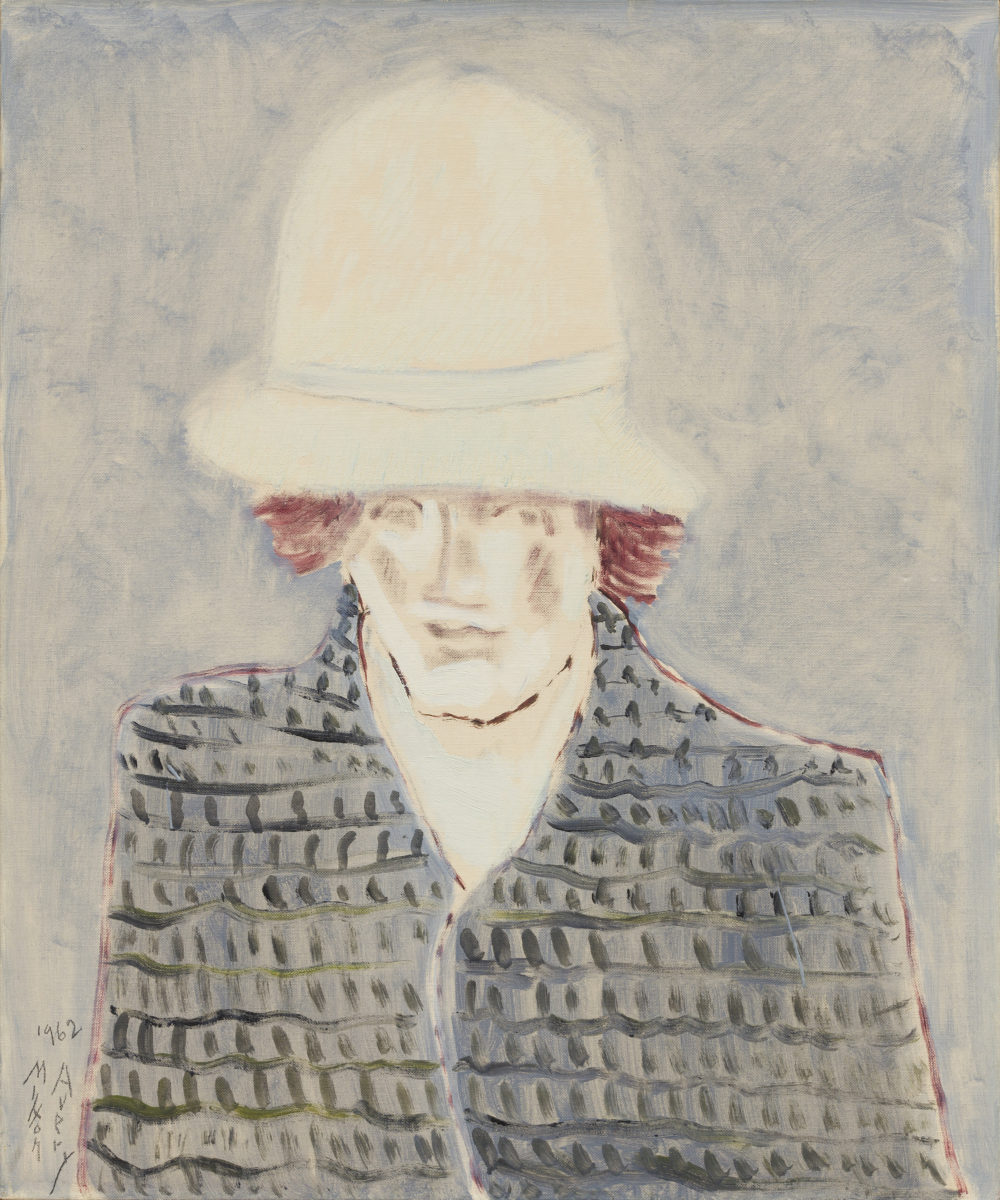

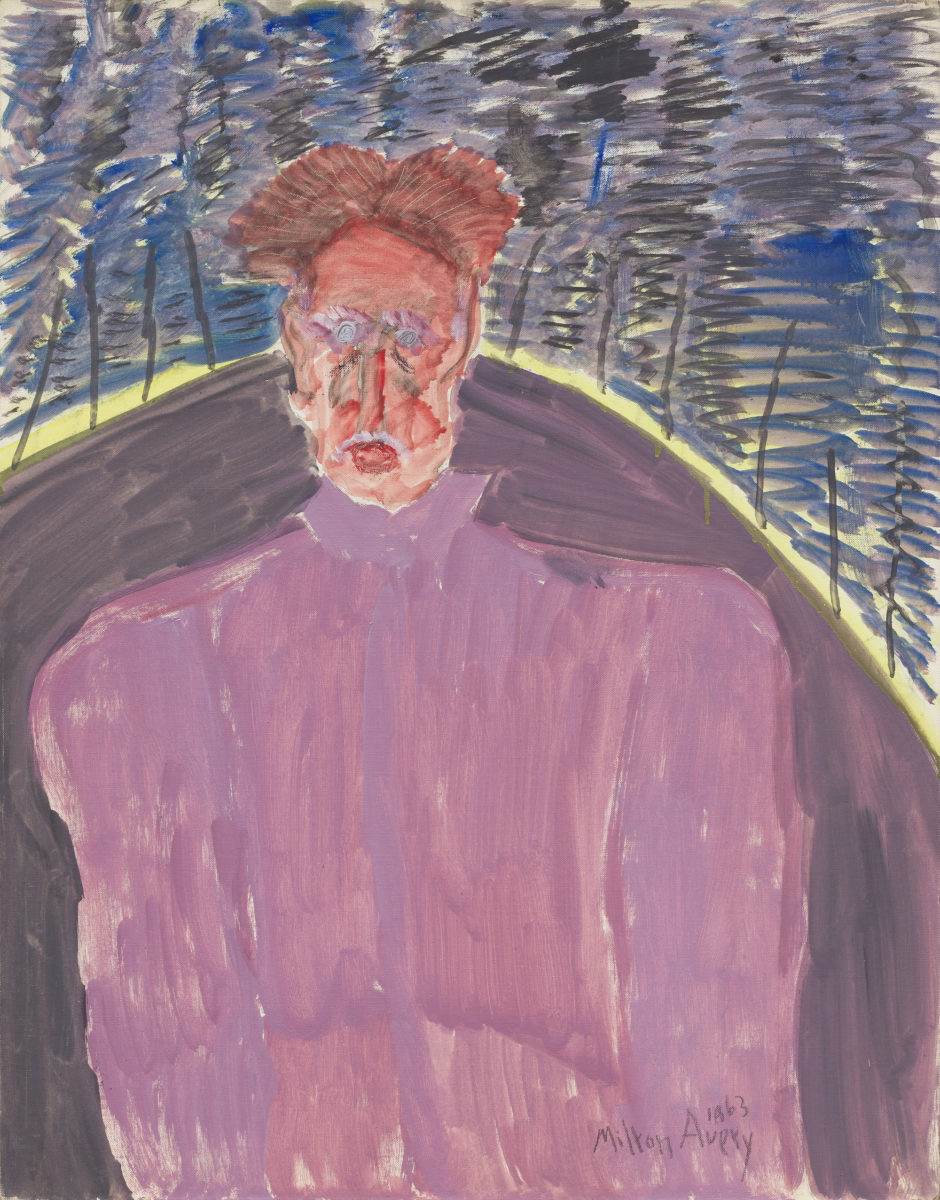

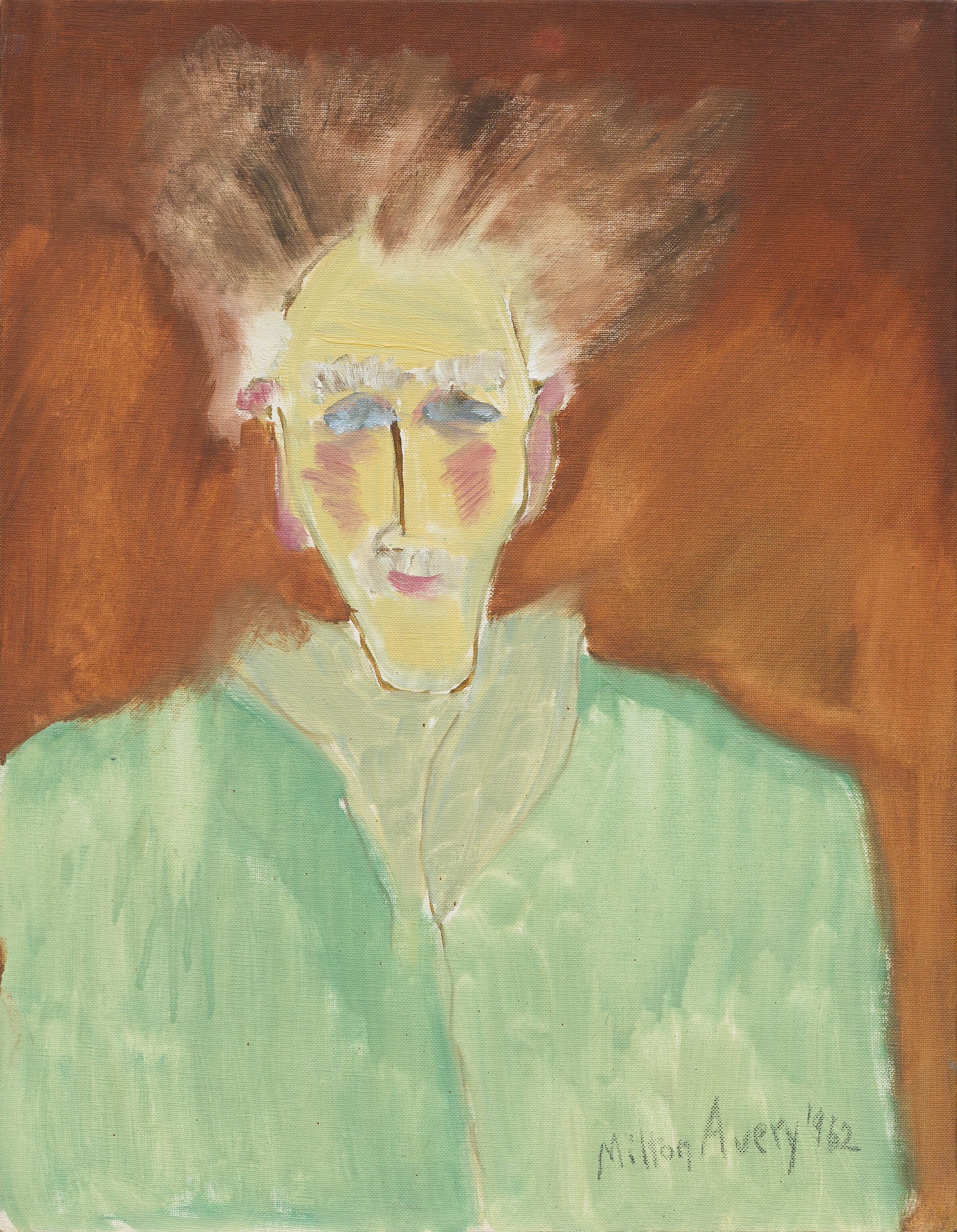

In the rush of 1930s American Scene paintings Avery was criticized for being too abstract; later in the 1950s he would be criticized for not abandoning natural forms to join the wave of Abstract Expressionism. He never changed to please his critics; he stayed true to his own vision of the world; he relished his own normality. The late portraits evoke the world around him with a bold lightness: he’s not creating to conform, he’s capturing the life around him as he’s living it, and there’s a joy in that which radiates from his work. It’s the same joy that many find online in the chequerboard platforms that make up so much of our day-to-day screen-time. It’s art as a means of memory, and memory is a fierce form of love.

So Avery, like Bonnard, and like many artists before him, opens the door to the possibility of accessible individual experience: we see the world through his eyes. The title given to Bonnard’s recent retrospective at Tate Modern was The Colour of Memory, and with good reason; it is through vibrant or unexpected hues that perspective is realized. The same goes for Avery. Walking around the exhibition of his Late Portraits, currently showing at Victoria Miro Gallery in Venice, the colours of his voice become clear. In Lavender Girl (1962) we see his daughter March—no longer a girl, she’s a Lavender Girl: she embodies colour itself. Her skin tinged with the hue of love, the violet tenderness of fatherly affection, her head cocked, her legs curled and purple, resting gently on the protruding semicircle of a white coffee table. In Sally by the Sea

(1962) his wife’s face becomes a reflection of the sky, shaded blue and white, a cloud caught in the dark hood of her hat.

Love colours the world around us, and Avery’s work may just be one of the greatest examples of that. After all, if there’s one thing that really unites all the “normal people” in this world it has to be this: we can look with love, and see the simple pleasures of our reality anew.

All images © 2019 Milton Avery Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London 2019. Courtesy Milton Avery Trust and Victoria Miro, London/Venice