New York- Ming Smith has been living and working in New York since the 1970s and is the first black woman photographer to be featured in MoMA’s permanent collection and to join the Kamoinge Workshop photography collective. Today, an exhibition of Smith’s work is on display at MoMA titled Projects: Ming Smith. This exhibition offers a critical reintroduction to a photographer who has served as a precedent for a generation of artists engaging in the politics and poetics of the photographic image.

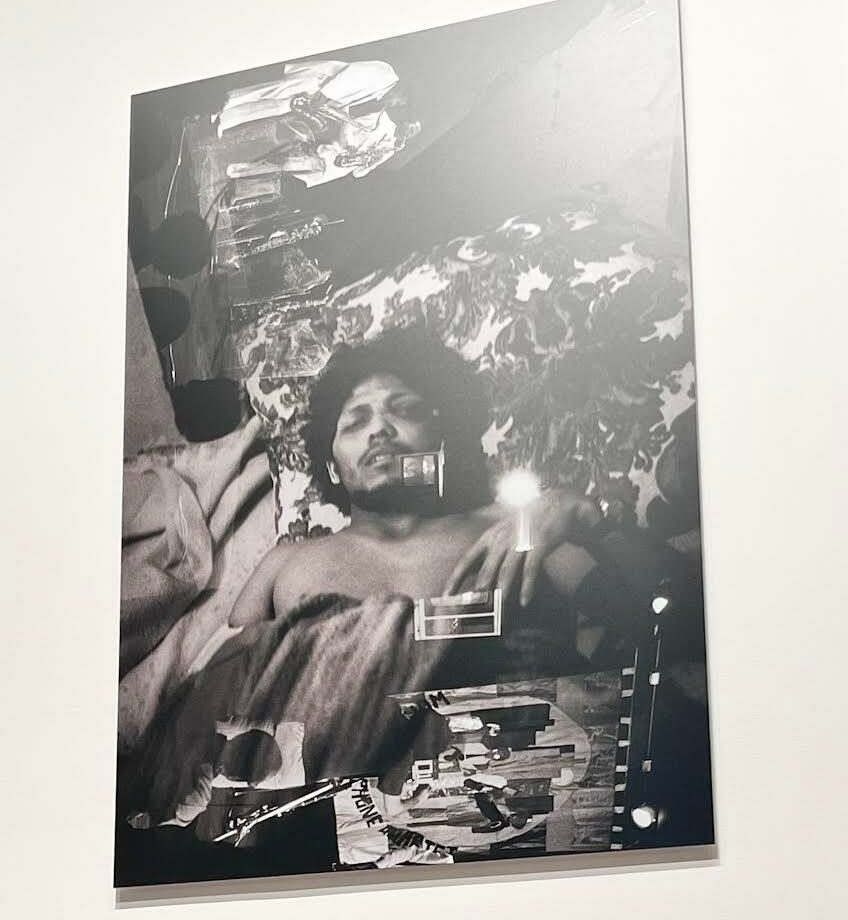

The exhibition space features Smith’s monochromatic photos, which have been distributed across the walls in a series of collages on one wall, and across from it, an entire wall has been covered with an enlarged print of Circular Breathing (Hart Leroy Bibbs) showing a man surrounded in darkness. There are two light sources, one coming from a window behind his head, and the other light source is emitting from the man’s hand which partially lights his face.

The images in this show provide a glimpse into Smith’s life throughout the 70s and 80s. Her photographs capture funeral processions, intimate moments between strangers and pictures of Smith herself. Ultimately, her works capture humanity in all of its complexity.

There is a surrealist undertone to Smith’s work, deployed through her manipulation of shutter speed, which activates the static image through motion and blur. Similarly, her use of paint adds multidimensionality to the work and invites the viewer to engage with the picture in a new dimension. Whether photographing a person, landscape, or still life, Ming’s images are imbued with a sense of vitality and an intimate knowledge of her subjects.

One of Smith’s most striking images is a multi-exposure photo of a man lying down on a comforter with a distraught expression. Aptly titled Oolong’s Nightmare, the photograph emits an uneasy feeling. Smith has masterfully utilized multiple exposure photography to display two additional photos on top of the original image. A picture of a jazz club emerges where the subject’s blanket folds into darkness, perhaps exposing the subject’s subconscious thoughts or a reference to the photographer’s.

Invisible Man, Somewhere, Everywhere, and Self Portrait Trio are the only two photos in color in this exhibition. The oil paints used on these prints are so subtle that they could easily be missed. Rather than overpowering the image, these painterly additions are in an ongoing conversation with the photographs that they grace.

Of course, Smith’s work is deeply rooted in her experience as a black woman living and working in America, and her work has inspired a new generation of artists today. It is easy to see parallels between Ming’s work and contemporary photographers such as Eric Hart Jr. and Andina Marie Osorio.

Ming Smith is a creative pioneer, and her work has been exhibited at major institutions like the MoMA, the National Museum of African-American History and Culture, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the Studio Museum of Harlem. Overall, the exhibition serves as a reminder of Smith’s essential and enduring legacy in photography.

Words by Moshopefoluwa Olagunju