Eloise Hendy meets with Mire Lee at the Tate Modern to discuss her Turbine Hall commission, her origin story and why she enjoys watching her works fall apart.

“I never actually wanted to become an artist,” Mire Lee confesses. “It’s just one thing that I never wanted to become”.

I’m sitting next to Lee in an empty cinema room in the bowels of the Tate Modern, and this admission takes me aback. There are, after all, just a few metres of concrete separating us from the vast expanse of the Turbine Hall where, at the beginning of October, Mire Lee will be staging her most monumental installation yet, as the ninth Hyundai Commission artist. Of all the possible commissions an artist could get, there aren’t many bigger – literally and metaphorically. So, it is quite funny to hear Lee disavow any desire to become an artist at all.

“Going to art school was kind of an accident,” Lee continues, “because we do this one big national exam, and I failed at math. I wasn’t left with many options to enter a good university with a ‘good name’. Because you have to do the full sweep of subjects in Korea,” Lee explains. “Korea has a very oppressive type of education system. Literally everybody just studies for more than a decade to enter a university, but without clear orientation of what they like. It’s very elitist,” she says firmly, with a slight frown. Lee decided her only option was to change her course. “I was somehow confident,” she tells me, “because art school has a considerably lower grade to enter. It’s still the same good name university, but you could enter with far lower points.” So, basically, her entire art practice and career hinges on failing one math exam? “It was a really superficial choice in a way, because I wanted to go to a good university, a privileged university,” Lee says. “I just turned to the sculpture department. That was the least popular one also,” she notes. “We have painting, sculpture, ceramics – the departments are very conservative categories. But sculpture was the most unpopular one,” she says lightly. “So that’s how I entered the art school”.

As origin stories go, it’s not the most romantic. But then, this is the artist who, in a 2022 interview with Frieze, called sculpture stupid. “I’ve always loved the rigidity, or stupidity as I like to think of it, of sculpture as a medium,” Lee said at the time: “there’s so much of it that’s hard to alter”. Reading this for the first time, I felt a thrill run down my spine – the same sensation I get hearing Lee profess her choice to study sculpture was “superficial”; a neat trick to get around a hierarchical education system. There’s a kind of anarchic quality to her honesty, in her refusal to take herself, her practice, or the art world at large too seriously.

If Lee became an artist by “accident,” it was a happy one at least. “I think as a younger person, I wasn’t happy about the courses because I thought they were too traditional,” Lee tells me. “But, secretly, I was really enjoying it, and I think I was also, like, kind of good at it”. I stifle a laugh as she says this. “Kind of good” is quite the understatement. But it’s the pleasure Lee found in sculpture that is more interesting, I think. “I actually really, really enjoyed working with my hands,” she says plainly, and it is clear she is referencing not only tactility, but labour – the embodied, manual work of creating art. Having been trained to handle successive, traditional materials – “stone, clay, wood, metal” – in her last year at Seoul National University, Lee took on a new major: media art. After learning “a little bit of programming and motor,” as she puts it, a new element was added to her emerging practice. “From there on,” Lee says, “I started to work with kinetics”.

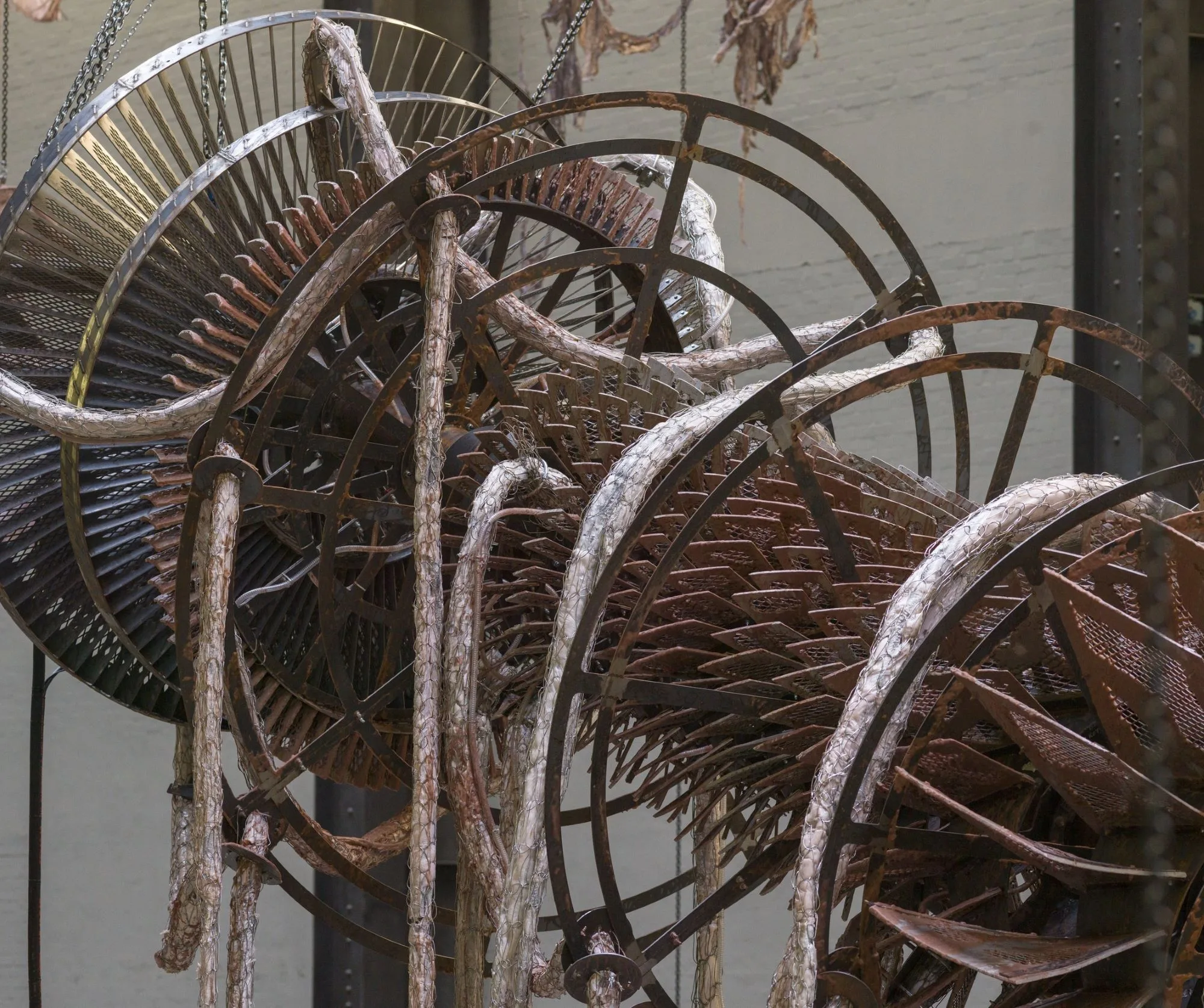

Already, Lee has summed up her sculptural practice, even if unintentionally. Her works take you aback. They are anarchic, embodied, tactile and absurd. Material is everything, but it is also torn to shreds, or twisted – made to look as if wracked and ruined. Motors turn, steel rods jut, and hoses pump viscous liquids: grease, silicone, oil. There is often a dark humour to Lee’s works, but, at the same time, they are great tragedies. Her installations look like shipwrecks, alien planets and dystopian factories, riddled with undead machines. They also look like innards. They ooze and churn and leak and shit concrete. They whir and stink; drip, rip and pour. In each work, it is clear to see Lee’s pleasure in handling materials – working with and against them at once – while also seeking surprise; a thrilled spine. Her kinetic sculptures have a life of their own; things happen by accident.

“It’s something very vague, that I feel very strongly,” Lee says carefully. “Wanting to get somewhere, but without knowing where the place is. Often I need to make a big scale work,” she notes, but the motorised movement of her sculptures stems from a similar urge too. “I always wanted to do something that I cannot handle completely, so that I would always see something surprising,” Lee says. “More existentially I think it gives me a purpose – to labour to solve problems,” she adds thoughtfully. But then, she changes her mind. “Or, not to solve problems, actually,” she says. “With my earlier motorised work, I had so many technical failures. More than half of the work didn’t work in the way I wanted”.

This led to some interesting early shows, Lee tells me. “It was all about trying to make it work more or less,” she says: “We tried to make things work and I was very stressed and had lots of crazy episodes”. For instance, in one of her first shows, in 2016, she “deployed” a large amount of liquid. “It was the first time I used a lot of liquid, and it was silicone oil back then,” she tells me. “Now I’ve turned more to organic materials, but back then it was silicone oil and I used the wrong type of pump. It was my first big, sizable installation and it started to leak,” she recalls, remarkably calmly. “It was a museum in Seoul and I was going there at 6AM, every day, with a squeegee, to scoop up all the liquids that flew out. It was so, so insane,” she laughs. “There’s so many episodes,” she continues. “Like, in another museum – because it’s kinetic work, it draws people in automatically,” Lee notes, self-effacingly. “In a group show, it often becomes an attraction point. So, then there was one person who came to the museum, and my work was, like, not functioning on that day,” she says lightly. “It was a group show with 30 artists, and the person wanted the museum to refund the ticket because she came to see my work and it was not working.” Lee shakes her head softly and grins. “I think before I was really anxious and stressed out,” she admits. Then, in what I’m learning to be classic fashion, she undermines the very premise of what she has just said. “It was a struggle, but in a very fictional way. It’s art at the end of the day”.

While this offhand attitude to art in general is, again, delicious, I can tell Lee genuinely did “struggle” to keep her work functioning. “I really tried all my best to keep it together,” she stresses. Yet, at the same time, I sense this was largely on behalf of stressed-out curators and institutions, who weren’t used to having silicone oil leaking all over their white cubes. And, Lee then admits that really, she “enjoyed seeing it falling apart.” Now, her attitude has shifted utterly. “Probably I’m too relaxed now,” she says. “Amongst all this chaos, it allowed me to think, if the work itself is crude and it doesn’t have a definite contour, and it is itself confusing, that sort of doesn’t matter,” she notes. “Because I admire works that are uncontainable. But,” she adds, “in my case, sometimes it’s just a literal situation. I think the Venice Biennale work was, maybe, half of the time not working.”If Lee is more relaxed about her works “not working” now, it is in large part because she has leaned into the strange enjoyment she gets at “seeing it falling apart”. “I think I got very used to this intensive failure situation,” Lee says. “Somehow, in a very masochistic way, it became a part of who I am or what I do”. Malfunction and precarity have become part of her practice in other words. “I think risk is something that I like as a concept,” Lee professes. “I think any art I really, really love always somehow involves the vulnerability of the creator. That artist is out there and risking something,” she says, “either aesthetically or politically”.

Her biggest installation to date, and the first major presentation of her work in the UK, Lee’s new site-specific work for the Turbine Hall may also be her biggest risk yet. It’s still a couple of months until the opening when we speak, and I’m eager to hear what she has in mind for the notorious, colossal space. “The first very first proposal, I wrote I wanted to create something like a mechanical womb,” she tells me. “The project is a little bit like a factory where the work produces sculptures, and during the display it keeps on producing works and then the display populates, the sculpture populates”. Initially, she was thinking of the hall as a big creature. “I was imagining something like a skeleton inside,” Lee says, “as if it’s a huge animal’s interior. Bataille has this comment about the animal body and human body,” she says lightly. “Animal body, your mouth and your anus is on the same level,” she explains, and an image of Londoners marching directly into a giant anus comes into my mind unbidden. “And then there is ‘turbine’,” Lee continues. “I wanted to make a turbine.”

Lee is totally nonchalant as she announces this. Her first idea was to buy a jet engine, but she and her team quickly realised this would be too tricky, and too pricey. So, she’s making her own, brand new turbine, to set in the Turbine Hall. “Because it was an industrial production site,” she notes, “so I somehow wanted to recommission the things that were decommissioned.”

For many artists, filling Tate Modern’s massive innards would seem a daunting project. But Lee seems to be relishing the challenge. “I love to work with big scale,” she tells me. “If a space is really big it’s very easy to make the sculptures look totally tiny. That contrast is quite fun.” This isn’t’ the only reason she’s interested in monumentality though. “I think the aesthetic experience of monumentality, if it’s human made, is somehow related to the experience of violence,” Lee says. “When I see something monumental, I’m consciously thinking about how so many human labours have been put into this thing. And then, the fact that there was one person who had an idea to build this,” she adds. “It could be an architect, could be an artist, or could be a dictator, whoever – there is a class division,” Lee stresses. “There is not just a labour and ruling class but also a person who gets to create and another person who executes, who builds. So I think this inequality itself is overwhelming”.

This overwhelming aesthetic experience and recognition of inequality gives monumentality a certain underlying tragedy, Lee suggests, and it is this that she is drawn to. “I want to somehow be able to make a monumental work that could somehow include all these feelings we have in front of something monumental,” she explains. For the Tate commission, for instance, she wants to “make the sculpture sort of look sad”. Yet, at the same time she also says she wants “to make a work that feels warm”: “I think it could be something sad, but I think it’s also something warm,” she muses.

By way of an example, Lee tells me about an advisor she’s working with on the project: “He’s a metal specialist. His name is Stefan”. Stefan recommended Lee look at miners’ changing rooms as a reference. “I loved everything about it,” Lee gushes. “You have your own basket, and it’s on a pulley system,” she explains. “It gives out this masculinity. It’s a very harsh industry, and it’s a collective image, yet somehow you become anonymous,” she notes. “But then the basket itself is your own space”. I’m reminded of Lee’s first description of the new work: “a mechanical womb.” Previously, Lee has said she is fascinated by Friedrich Kiesler’s Endless House, which, in Kiesler’s vision, was to be “endless like the human body — there is no beginning and no end.” Explainin no g her fascination with this idea, Lee told Frieze that, to her, “it carries the warmth of the womb and the darkness of a torture chamber at the same time”. Sad, warm and harshly industrial, will this new mechanical womb turbine be a torture chamber too?

“I think that’s my own gradual realisation that what we as humans feel closest to are also the most horrifying things,” Lee says candidly. “If I am interested in the grotesque, it is because something that I feel the warmest to and closest to is so intensely grotesque,” she declares. “For example, my mother, or my relationship with my mother. I really, really love her and cherish her and sometimes when we fight it really feels like I’m her lover or something, and then there is this deep disgust, really the most grotesque feeling.” Lee pauses for a moment, as if to let the words sink in not just for me but for herself too. “But my mom is the deepest warmth to me, so there is this constant tension,” she continues. “It’s not just grotesque, it’s entangled with the thing that I find the most precious, or that I cherish the most,” she stresses. “Or if it’s monumentality, then it’s very combined with sadness, or I find it actually endearing or something. So for me, it’s always both.”

Now, on the Southbank then, a monumental tragedy entangled with “the most precious” warmth. A womb that is an animal and also a mine. Speaking to Lee, I can’t quite imagine exactly what will confront the public in October, but I am sure it could not be more fitting for a gallery that is also a ghostly industrial space. A sculpture that populates, procreates, reproduces and breeds. “As an artist, if I really want to make changes or if I really want it to be meaningful and powerful, the work has to be first powerful, and then not just one time, but over and over again,” Lee says finally, “because I think to be inspired by art, it’s not just one encounter, but it accumulates, you know.”

Written by Eloise Hendy