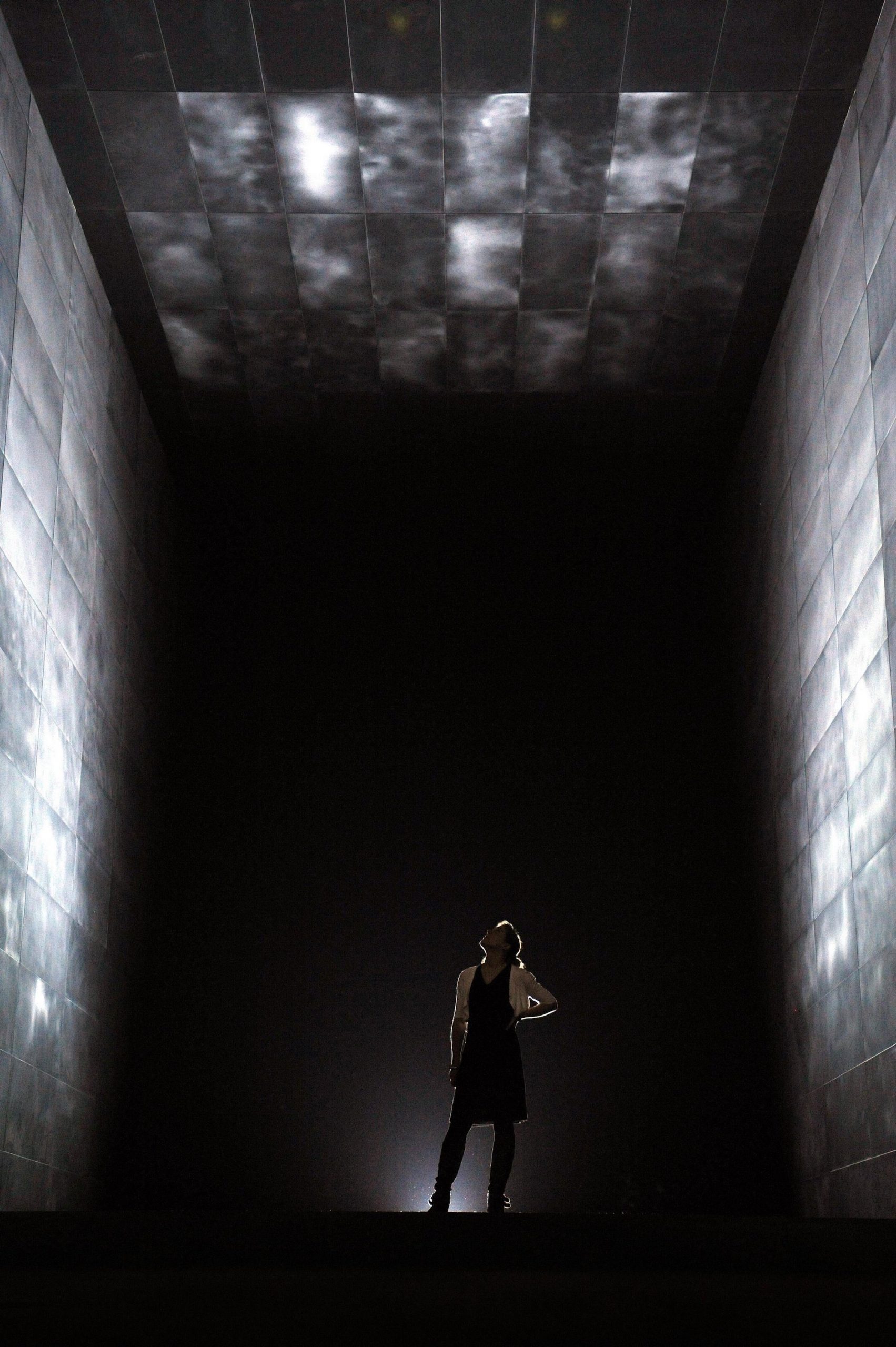

I hadn’t planned to visit an installation of a giant shipping container at the Tate Modern. The work of Polish artist Miroslaw Balka, part-architecture and part-sculpture, resembled a black hole. Nonchalantly titled How It Is, the giant steel structure took up most of the cavernous Turbine Hall.

It was 2009, my daughter’s twelfth birthday, which we planned to celebrate with a trip to the Globe theatre. On our way there, we decided to pop into the Tate. I was stunned immediately by the monumental size of Balka’s work, half the size of a football pitch, and powerfully minimalistic.

I studied architecture as an undergraduate and have always been fascinated by how different environments are constructed, both positive and negative. By placing this structure right in the middle of the huge hall, it carved out space within space. It seemingly cut into the open area around it, while somehow enhancing it in the process. It was as if the whole Turbine Hall had been turned inside out to reveal an inner darkness.

It is embarrassing to admit that I fear the dark, and sleep with the lights on if I am alone. But I insisted on challenging myself, and squeezed under the container itself, which was raised on two-foot stilts. I am not very tall, but this was a claustrophobic space and reminded me of the shadowy interior of the catacombs in Rome or the pyramids in Egypt, both of which made me break out in a panic when I visited them.

“It made me think of how emptiness can be so complete in itself”

I could hear the “thud thud thud” of footsteps above in the metal chamber, and they felt comforting in their companionship. I couldn’t see much but I could hear those movements: each small step amplified and echoed in my ears as I roamed around under the container. It was a reminder of how even the tiniest shift can have a cascading impact. We have to keep moving forward so someone out there might not feel as alone.

There was a short ramp leading up to the steel box. You couldn’t see anything inside. It was pitch black, and to my mind alluded to the biblical Plague of Darkness, images of hell, and black holes in outer space.

This artwork is also a reference to the recent horrors in Polish history with the ramp leading to the ghettos in Warsaw, where members of the Jewish community were forcibly carried away in large metal trucks. It is a sobering reminder of how swiftly oppression can take hold, and how quickly fascism can raise its ugly head even when we believe that we are far from it.

“Entering the darkness of How It Is, you have to put complete trust in the artwork”

Entering the darkness of How It Is, you have to put complete trust in the artwork; you don’t know what’s waiting for you inside. It reminded me of the trust that refugees and immigrants place in the system as they propel themselves forward into the unknown, often confronted by the endless, hostile waters in small inflatable dinghies. So much resilience, so much strength, so much determination in these acts that we often choose to ignore.

As I stepped into Balka‘s abyss, 12 years had passed since I had my daughter in a hospital in India, via a C-section after three months of complete bed rest. I remember that acute sense of claustrophobia I had felt in an enclosed room on the ward as seasons passed outside.

Ten days after that traumatic birth, before even we could settle in as a mother and child, I haemorrhaged and lost two-thirds of my blood along with huge, fist-sized lumps that oozed out of my body as I slowly lost consciousness. I slowly inched away from life, and my daughter. But somehow I held on with tight nails and returned.

As I felt my way around the container in London 12 years later, slowly creeping along its walls, for the first time I came close to what I had felt that day in hospital, on the verge of death, in that moment of waking up again. There was a light at the end of the tunnel and all I could do was to focus completely on it. There was no other way.

I had never talked about that experience with anyone, just buried it deep, agreeing that I was lucky to be alive, so fortunate to have a healthy child. No one had ever asked me how I was after I survived, and I received no therapy for that trauma.

“Even when we think there is no light, we are capable of adapting our perceptions to what we cannot see”

Until that moment in the gallery, I hadn’t realised just how much I had been carrying that memory, even as I kept pushing it further and further down. As I was shut away with my thoughts, using my other senses besides my vision, and not having to pretend to anyone that I was OK, I felt more alive than I had felt for the full duration of my daughter’s life.

It made me realise that sometimes you have to confront darkness to be able to live in the light; to experience absence in order to notice presence; how even when we think there is no light, we are capable of adapting our perceptions to what we cannot see.

It made me think of how emptiness can be so complete in itself, which seems like a strange paradox. And that these bare pauses I had always felt so determined to fill up in my life, the way I found silence discomfiting, was because I didn’t want to be left alone with my anxious thoughts.

I found a sense of peace and comfort in my own senses and my thoughts that day. Emerging from the dark container felt like rebirth, like I had shed some of my painful memories by confronting them, and was turned inside out as new.

Professor Pragya Agarwal is a behavioural and data scientist and author of three books. Her latest, (M)otherhood, is out now