Misheck Masamvu is famous for his cars. The artist does up vintage automobiles and legend has it that you can spot numerous cars that have had the Masamvu treatment driving through the streets of Zimbabwe’s capital of Harare. Aside from restoring old cars, Masamvu is also known for other, more conventional kinds of art: he uses painting, drawing, monoprint and poetry in his work to negotiate themes of the spiritual and the earthly, and to blur abstraction and figuration.

As with most conversations these days, ours took place over video call, with Masamvu in Harare, where he has now returned to live, having studied art in Europe at Atelier Delta then the Kunste Akademie in Munich. His work has been exhibited all over the world since completing his studies in Europe, including the Zimbabwe Pavilion at Venice in 2011, and the Biennale of Sydney last year, but he is predominantly known in South Africa (where he is represented by Goodman Gallery) and his home country of Zimbabwe.

Masamvu’s latest monoprints, produced in lockdown for his first UK exhibition at London’s Goodman Gallery, are quite different to his previous works: large-scale oil paintings are florid investigations that run deep into his rich imagination, carving out his own space through the surface of painting and demonstrating a confidence in his place and position as an artist. It’s something that hasn’t come easily.

“I think when you start to try to make art, I guess you are more interested in trying to sell yourself, in terms of your ability, so you tend to over decorate things because you want to propose a certain image about yourself, your skills and stuff,” Masamvu explains. “But what I’ve learned over the years, is by actually trying to go towards a certain narrative of identity or image or story I was actually destroying a story that was building by itself.”

The title of Masamvu’s first UK show, Talk to Me While I Am Eating, which ran at Goodman Gallery London online in January and February this year, is a meditation on the idea of having ‘a seat at the table’, both literally and metaphorically. Things can often feel unequal in the art world: success in one room can feel like failure in another and navigating that can become part of any art job. As an artist, success can also mean audiences with powerful people and the title of Masamvu’s show plays on the way that kind of access can end up feeling more like an expectation to perform the role of artist as charming supplicant. Even when an artist is one of the wealthiest and most powerful people, they are still often expected to be the entertainment.

“By trying to go towards a certain narrative of identity or image or story I was actually destroying a story that was building by itself”

“I think the answer is really in the title of the exhibition Talk to Me While I Am Eating,” Masamvu says. “I’m looking at the positions of privilege and who decides on who is privileged. And when you do have the privilege, how do you relate or apply it to others?”

For many Zimbabweans, including Masamvu, the path to peace in their country has been hard-won and the events of the decades since Zimbabwe claimed independence from Britain in 1980 continue to affect every aspect of social interaction. “What I’m dealing with is a space that is always choreographed,” he explains. “I look at this in terms of the politics of the postcolonial situation.”

Masamvu presents the idea of the art world dinner as a casting couch. It follows on from the ideas of artists like Judy Chicago, but when you add the post-colonial context of Zimbabwe into the equation, combined with the international appetite for ‘Contemporary African Art’, the conversation becomes more complex. Masamvu openly questions his own position within this environment, as he experiences it both in his home country and abroad. A section of a poem by Masamvu, also titled Talk to Me While I Am Eating, and included in his Goodman show reads:

“I am zipped in my mind space

Still participating in spaces of interaction to interrogate my capacity to deal with others.

To locate and focus on the source power at the table

The spilled

spoiled

broken table at the last supper.”

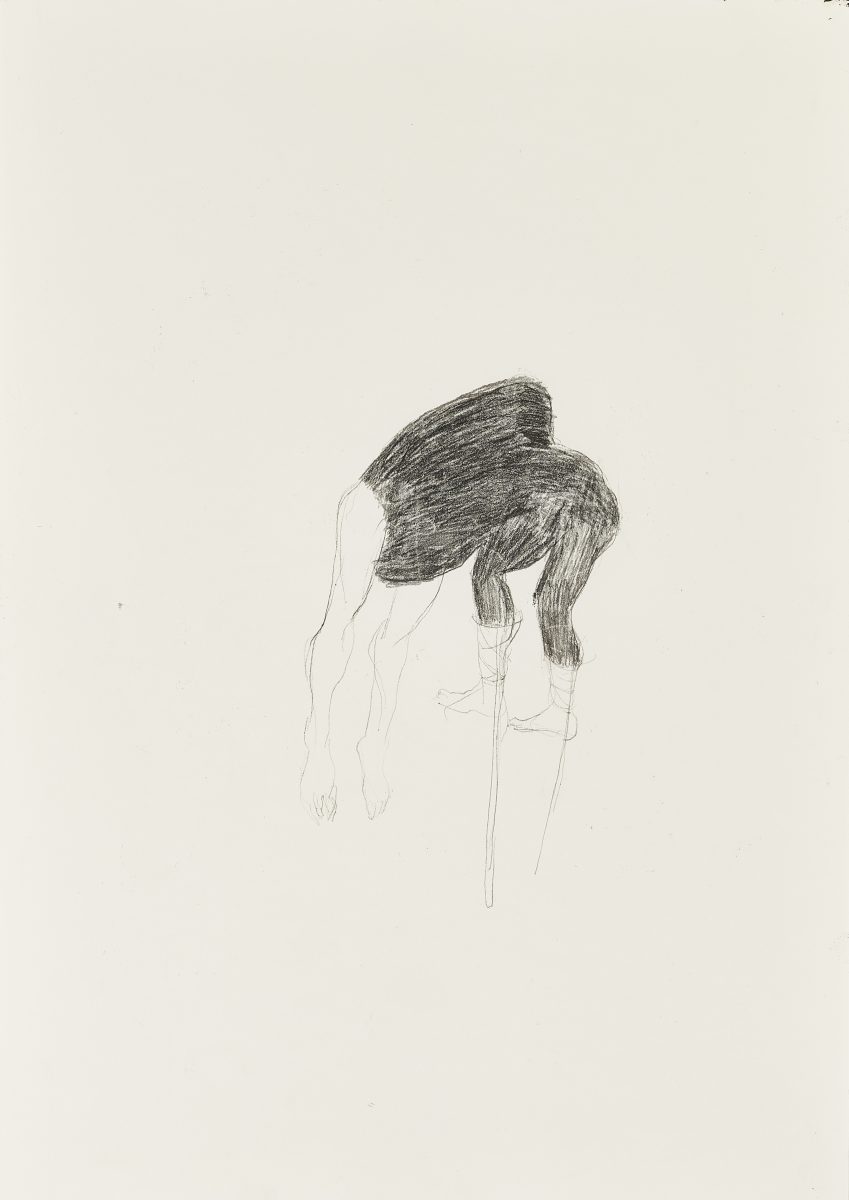

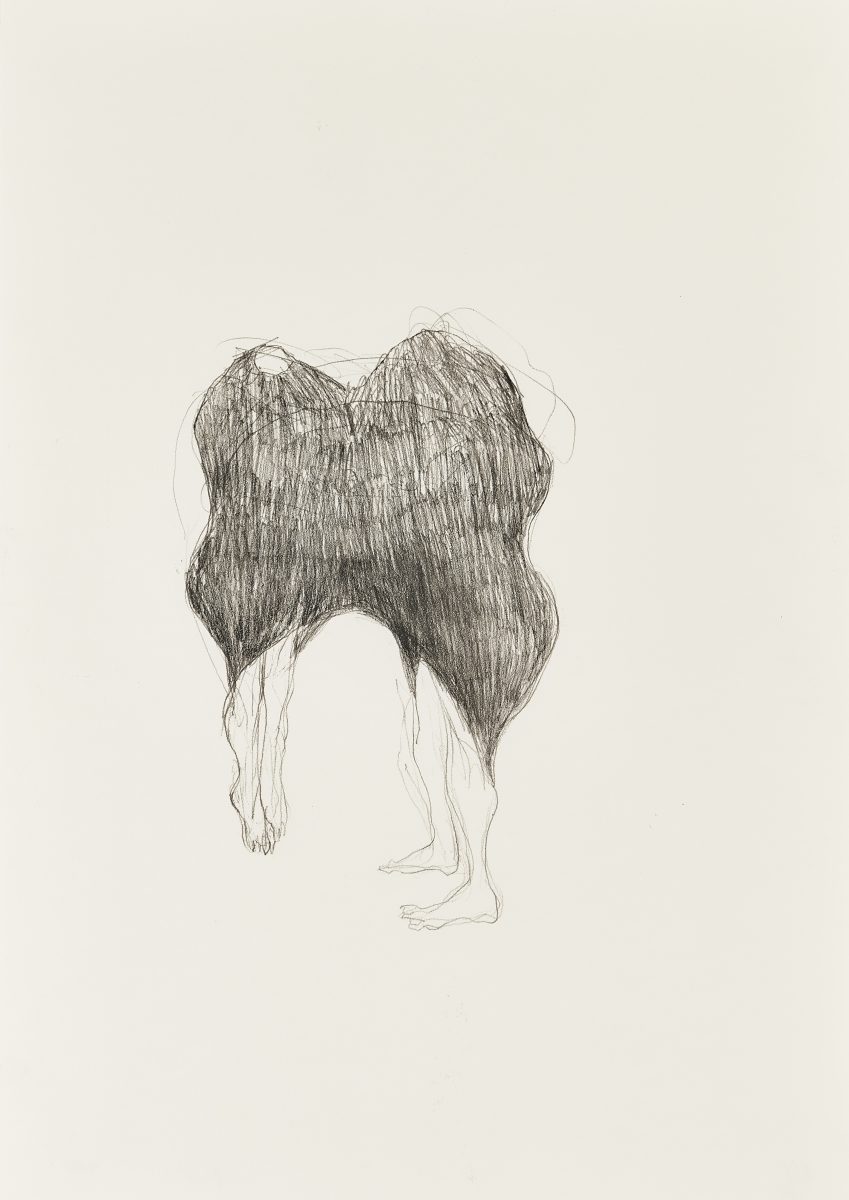

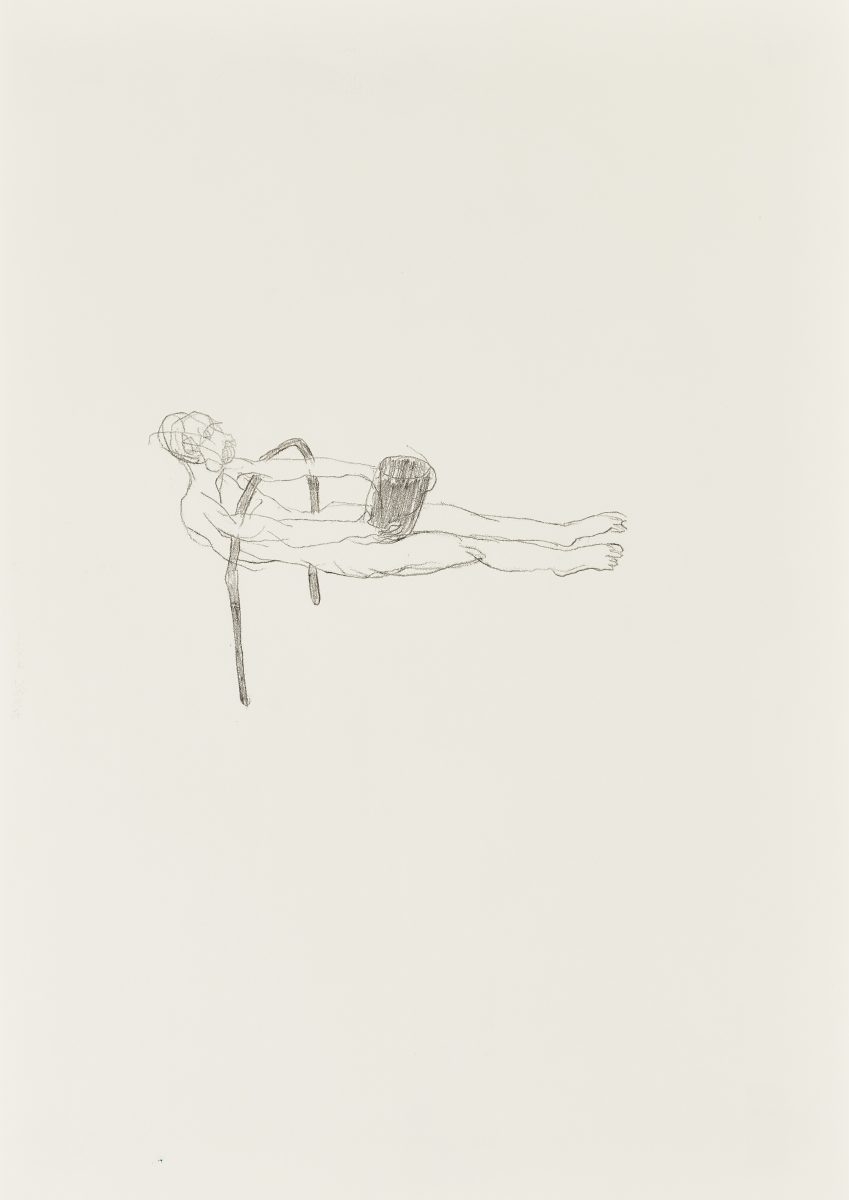

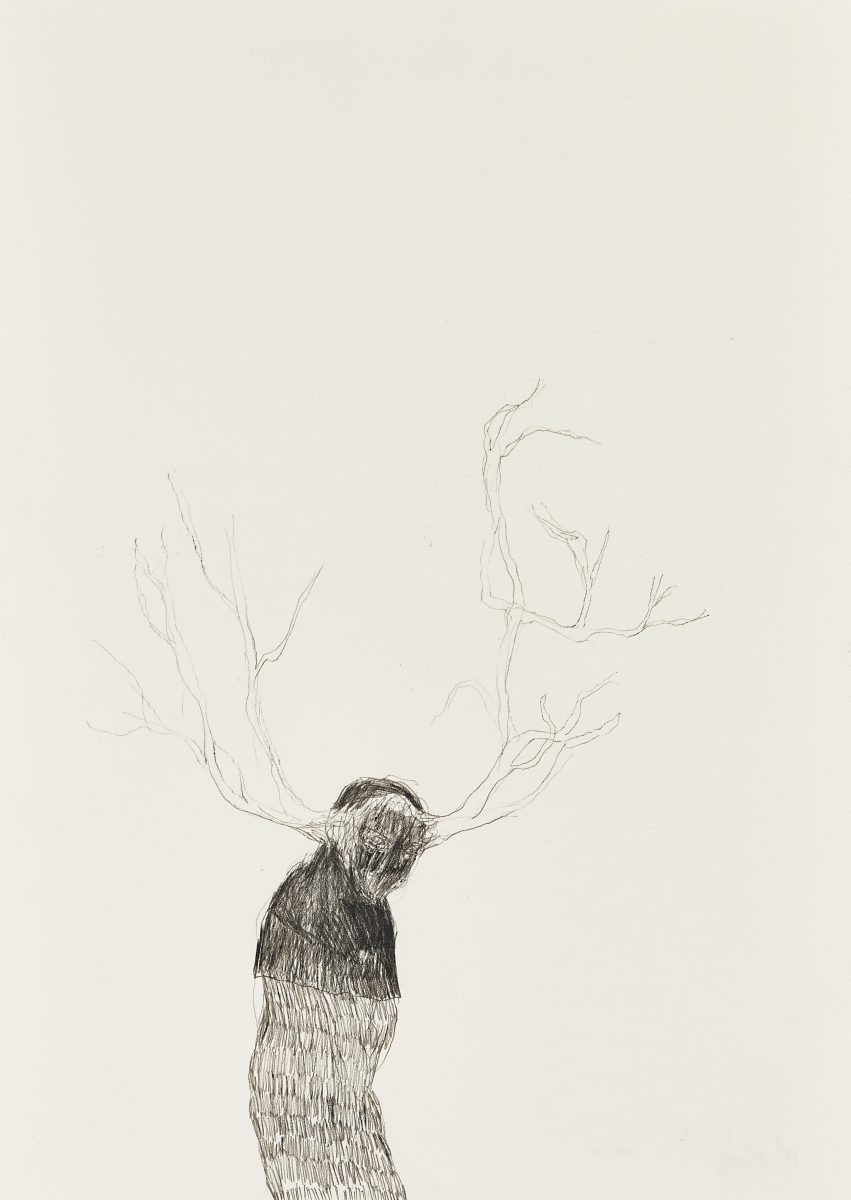

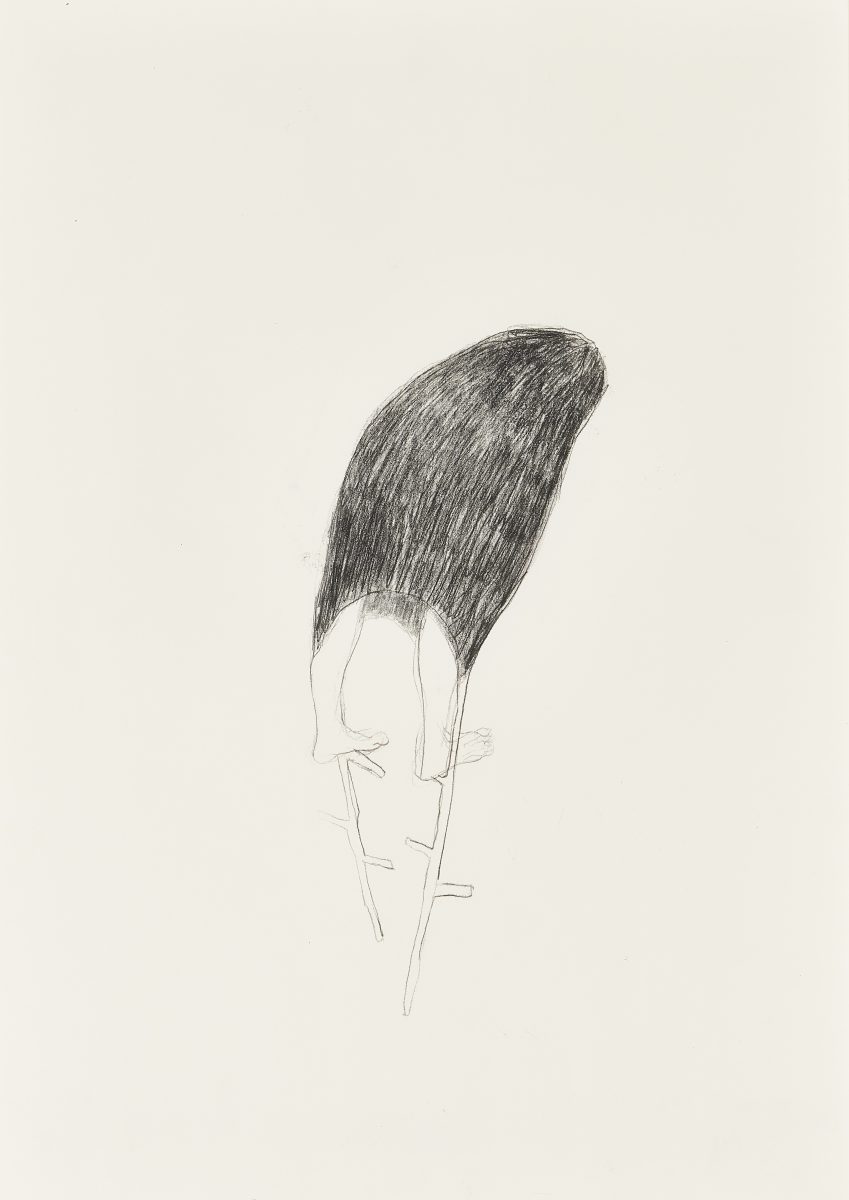

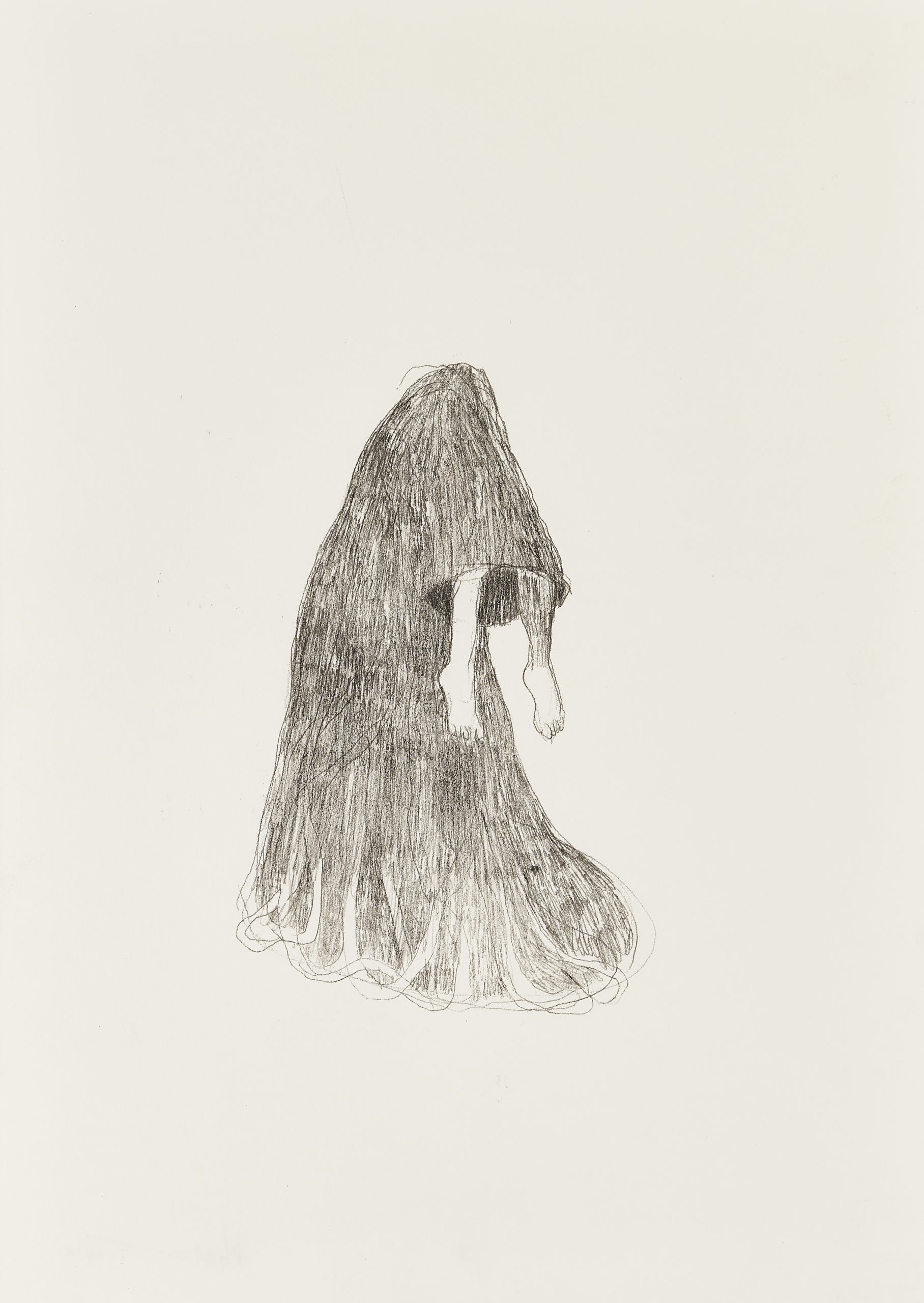

A series of new drawings show figures contorted, warped and pulled in different directions: one image of someone being consumed by a beast, Inglorious Chambers (2020) speaks to the discordant feeling of being at odds with your surroundings. Others such as Fenced Out, and Bundled Histories, represent the desire to disappear in situations where huge disparities in power, particularly at certain kinds of art world dinners, exacerbate inequalities of race, gender and nationality.

“The very first thing is to be true to that process of what you’re trying to put across”

When he talks of the times he has encountered this himself at art world dinners, Masamvu is vague about the details of what, when and who. But his malaise is evident. “We might ‘sit at the table’,” he says, “but we don’t have the understanding or the education to know how to actually use the tools that are assembled in front of us. So might you still find yourself at a disadvantage? Sure.”

The seat Masamvu alludes to is also the seat of opportunity at the table of the international art market, where conversations centre around exclusion while simultaneously categorising artists, and their value, according to their identity.

There is always going to be a schism between the commercial and artistic facets of the art world but it can be difficult for artists to leave observations behind when returning to the studio to make work. However, Masamvu embraces the contradictory in his work, and the success he has had to date. “One aspect is that there is this bottom line when you’re given an opportunity,” he says. “As an artist, you have to grab that opportunity within your own work before a platform like an exhibition or anything else is given. The very first thing is to be true to that process of what you’re trying to put across.”

Masamvu may be affected by the specificities of his situation but his works resonate far beyond and depict feelings familiar to anyone who has felt they don’t fit in. In paintings from 2020 such as Whispers in the Mist and Ephemeral Space, figurative forms emerge from abstraction and disappear back into it––just like an anecdote you didn’t quite catch, or a joke you didn’t get but laughed at anyway.