Each month In The Frame explores the role that art plays on the big screen. From classic noir thrillers to iconic television series, directors have turned to art history and contemporary artists alike to bring their vision to life. This time, it’s the Mona Lisa in Masahiro Shinoda’s Pale Flower (1964), an overlooked gem of the Japanese New Wave

No artwork has been reproduced, manipulated, commodified and meme-ified as much as the Mona Lisa. Today, we’re inured to seeing that famous face slapped onto lunchboxes and mugs, or else Photoshopped into oblivion. When an image achieves this level of instant recognition, it becomes paradoxically meaningless, decontextualised into nothingness. Any artist who references the Mona Lisa in their work risks being crushed by the symbolic weight of Da Vinci’s original portrait. Layered with historical and cultural context, it is a loaded nod to the history of western art and a sly jibe at the pervasive power of popular culture.

When a replica of the painting appears in Masahiro Shinoda’s Pale Flower (1963), the initial effect is one of comic incongruity. Long overshadowed outside Japan by the likes of Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu, as well as by more acclaimed New Wave contemporaries such as Nagisa Oshima, Shinoda has recently been reclaimed by audiences both domestic and international as a key player in Japan’s post-war cinematic explosion. His cynical visions of his nation’s warrior past and morally-compromised modernity retain their relevance today; his claim that “all Japanese culture flows from imperialism” rings uneasily true as the country debates abandoning its policy of state pacifism amid rising regional tensions.

A cocktail of yakuza potboiler and film noir, Pale Flower is a far cry from the Italian Renaissance world of Da Vinci. It wears its genre trappings with stylish appeal, the nocturnal nihilism of noir is run through a typically gangsterish plot of loyalty, murder, and sacred criminal codes.

“A cocktail of yakuza potboiler and film noir, Pale Flower is a far cry from the Italian Renaissance world of Da Vinci”

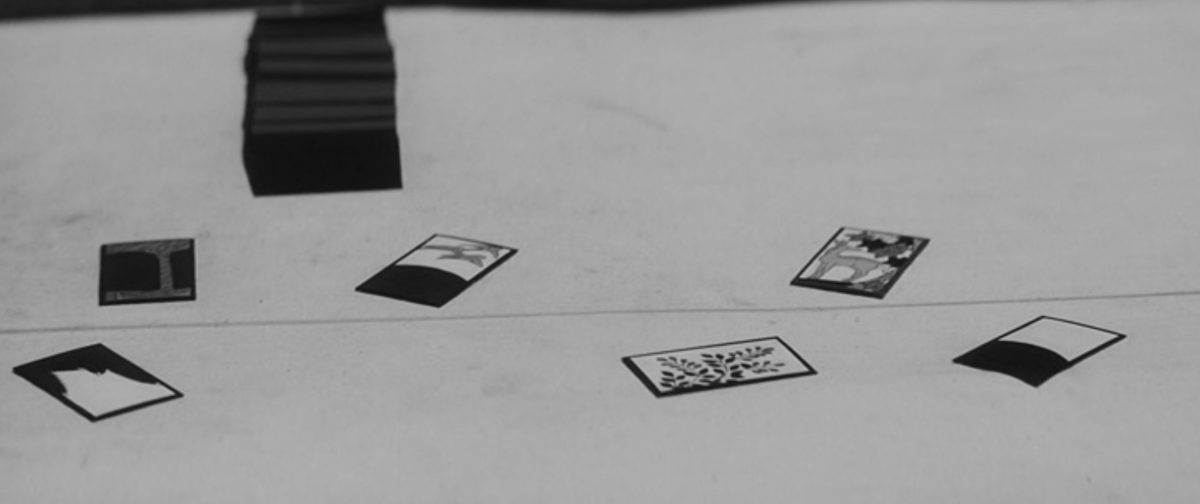

Muraki (Ryo Ikebe) is a mob hitman freshly released from prison onto the streets of Yokohama. Dismissive of civilian society and disillusioned by his boss’s willingness to let business decisions come before old-fashioned honour, Muraki retreats to underground gambling dens, where underworld types play at hanafuda and tehonbiki, traditional Japanese card games. Here he becomes warily enamoured of Saeko (Mariko Kaga), a mysterious high-roller whom he recognises as a kindred loner. But Saeko may be even more in thrall to her death drive than Muraki, and their cagey, unconsummated affair plays out against a backdrop of drag races, drug addiction, and contract murder.

Pale Flower traverses a number of hermetically sealed worlds, from yakuza society to the gambling dens, at once beguiling and opaque to outsiders. Part of the thrill of the film is precisely this hermetic quality, the sense that its characters operate according to prescribed, almost arcane rules. The exquisitely constructed gambling scenes are emblematic of this tension.

“The film’s Mona Lisa replica cracks the film open. It’s the clichéd nature of the image that brings both East and West into focus”

When Muraki and Saeko play at hanafuda, betting on “flower cards” adorned with peonies and paulownia, the rhythm of film’s cuts matches the rattling of the cards, the delirious calls of the dealer, and the percussive score of composer Toru Takemitsu. The rules of tehonbiki, or “matched draws”, are even harder for an outsider to follow, but Shinoda’s patient detailing of the game’s patterns of concealment and revelation wrings tension from every gesture.

If Muraki, Saeko, and the murky world they inhabit feel closed off to Western viewers, then the film’s Mona Lisa replica, in all its overfamiliarity, cracks the film open, and it’s precisely the clichéd nature of the image that brings Shinoda’s critical view of both East and West into focus. It hangs in the restaurant where two ageing yakuza bosses, former rivals turned business partners, discuss family and business. These men are depicted as venal, manipulative, and hypocritical, happy to settle down into bourgeois plenitude while men kill and die on their behalf.

When one chides the other for slurping his soup from the bowl, rather than with a spoon, “Western”-style, the significance of that second-hand Da Vinci becomes clearer. It is the type of artwork that a wealthy, grubby man would buy because he thought it indicated good (European) taste. It is reduced to its own iconicity within the western canon, and emptied out.

Where the hanafuda and tehonbiki are intricately staged, invested with ritualistic and sublimated meaning, perhaps a substitute for the sexual union that Muraki and Saeko never achieve, this Mona Lisa is just a cheap decoration.

“Imported Western tastes are shown to be nothing but window-dressing for greed and violence”

Unlike Oshima and Shohei Imamura, contemporaries at the Shochiki studio that played a key role in birthing the Japanese New Wave, Shinoda is not known as a political firebrand. But Pale Flower shows that he did indeed have a jaundiced vision of 1960s’ Japanese society as a stupefied, uncanny place, caught between Western consumerism and the unexamined violence of native traditions, and that he understood cinema’s role in exposing it. “Filmmakers should bear witness to the politics of their age,” as he once declared.

Pale Flower’s cheap Mona Lisa reveals the whole film to be constructed around a back-and-forth between Japan and the West, with Muraki the existential crook sucked into the resulting ideological vortex. As represented by the hanafuda gambling sessions, Japanese traditions are shown to be self-destructively insular; as shown by the fake Da Vinci, imported Western tastes are nothing but window-dressing for greed and violence.

Shinoda’s gaze is not inward-looking or closed-off after all: it is casting judgement on a nation at odds with itself. And it is looking back at us with that famous Mona Lisa smile.

Samuel Goff is a writer based in London. A former editor at The Calvert Journal, he focuses on visual culture in the early Soviet Union and the history of cinema

Available to watch on Criterion Collection: https://www.criterion.com/films/27604-pale-flower