In his only piece of published writing, Francis Bacon described the process of painting as “attempting to make idea and technique inseparable. Painting in this sense tends towards a complete interlocking of image and paint, so that the image is the paint and vice versa.”

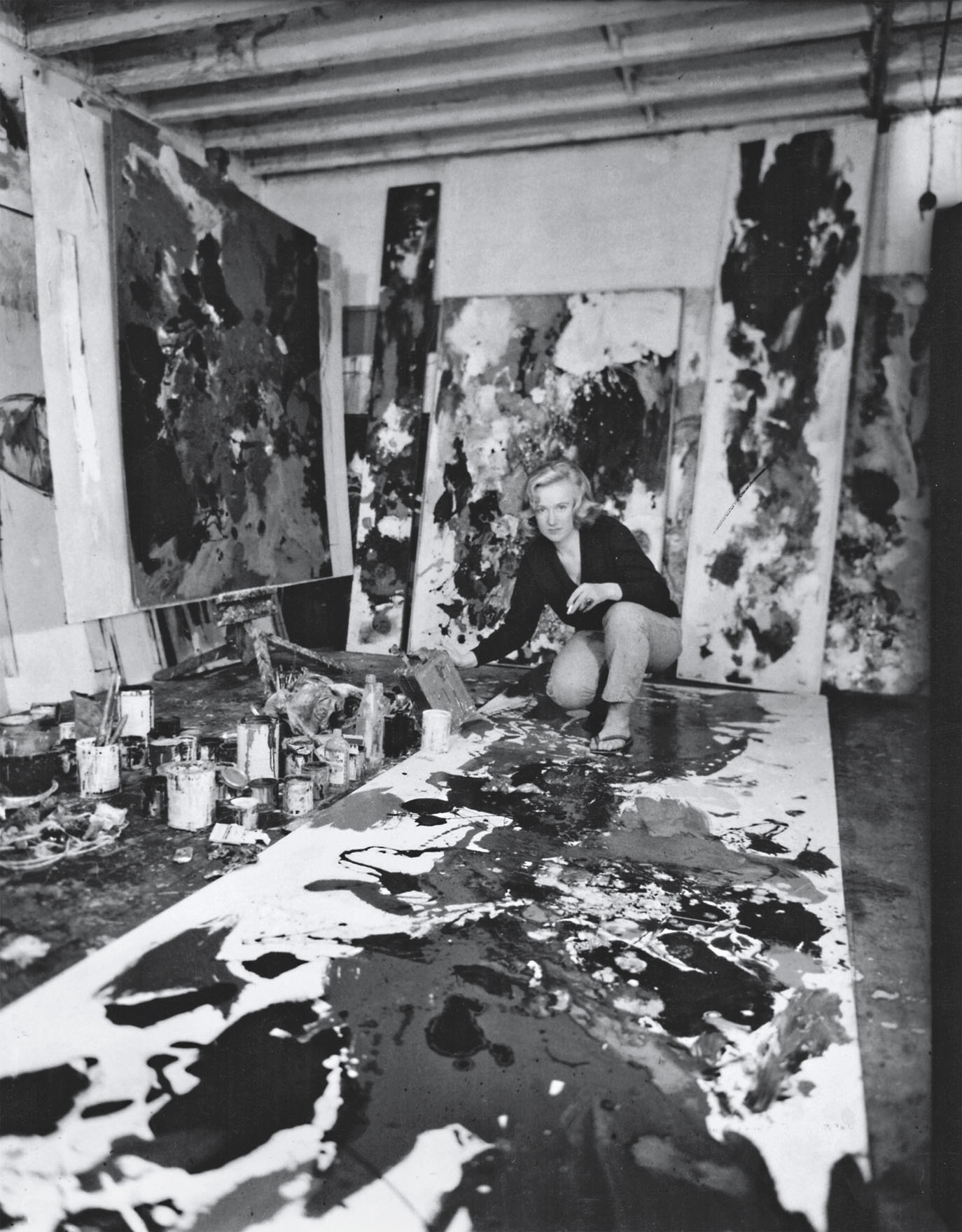

For his latest book, the Spectator critic Martin Gayford has synthesized a lifetime’s worth of conversations with the greats of modern painting (Bridget Riley, Peter Blake, Frank Auerbach, Paula Rego, Victor Pasmore) into swift individual chapters, with Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud having consistent recurring narratives. To Gayford these are painters united solely by an obsession with “what Gillian Ayres has defined as ‘what can be done with painting”, and that they happened to be working in London.

William Gear, Autumn Landscape, 1950-51. Oil on canvas, 178 x 127 cm. Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne © the artist’s estate

The challenges of painting now are the same as those that beset the post-war generation: how to keep paint working in the service of art when it is no longer necessary for the representation of things in the age of the photograph and the moving image. The abstract expressionists hoped to achieve greatness “through paint alone”, shorn of actual representation. A pure, austere ideal: one in which, it seemed, paint was the only thing which couldn’t be subtracted. William Coldstream’s way out was to find a new precision not based on photographic likeness but scale: a method that quickly became atrophied, then a “cliche” of drabness.

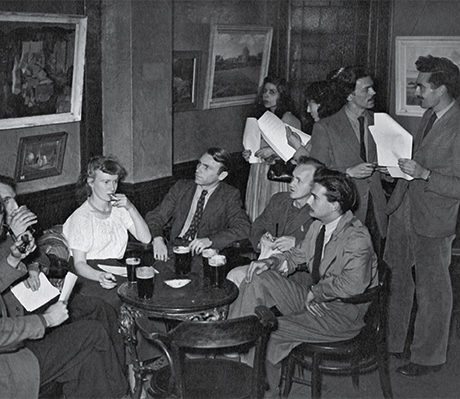

Among the terrible beauty of razed London, where heaps of rubble also suggested sumptuous possibility for rebirth and modernity, the fledgling artists had affairs, found spiritual mentors and worked in poverty, unless they were bankrolled by patrons. (Lucian Freud started out with one, but by forty was in debt, bribing demolition men with whisky not to knock down his council house while work continued slowly with his painting.) Artists were congratulating each other for “going abstract”, a phrase used by both Gayford and many of the artists he quotes. But for the most part these London painters were pushing the medium at a time when Britain was seriously lagging behind Europe in modernist sensibility. The public would write angry letters to the Arts Council when progressive work won public prizes. In 1951 the Daily Mail put William Gear’s work on their front cover in order to stoke public outrage, in the same way they might today superimpose images of Jeremy Corbyn to make it look like he is dancing a jig at a war memorial.

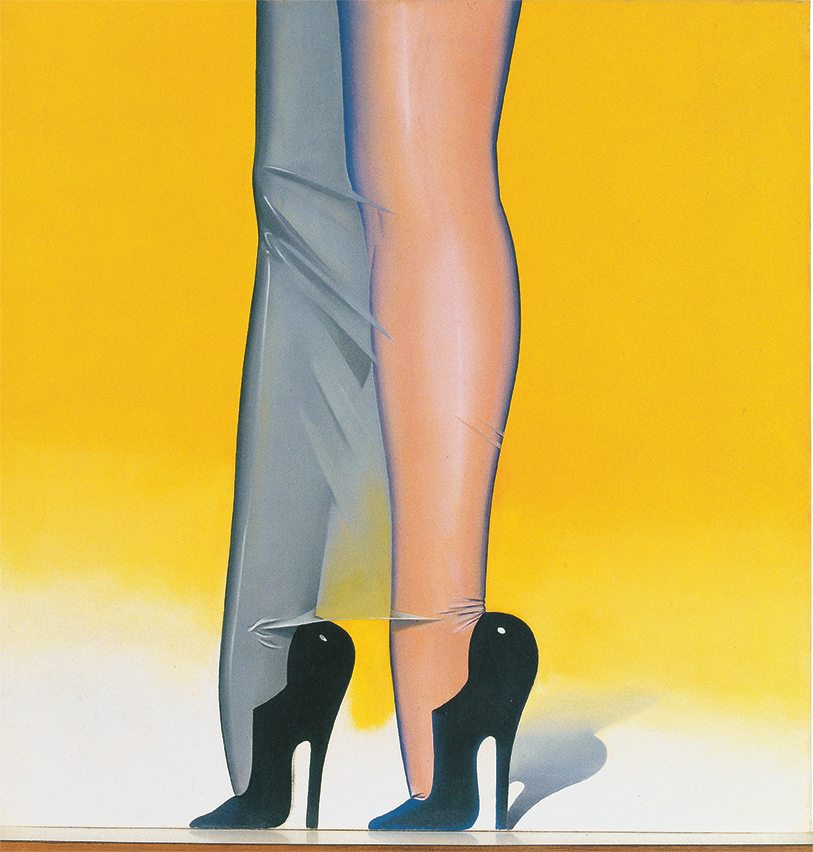

© Allen Jones

Now work from this period is some of the most expensive ever sold. And modern painting aping the innovations of that era tends to cash in, equally proving the aesthetic dominance of post-war innovators and making it seem like innovation in the medium has come to a halt. It’s that familiar, disheartening and untrue headline again, one that can’t help appearing every few years: Painting is Dead. A few years ago, the new trend that took elements from abstract expressionism but muted its power—and also sold for inordinate amounts at auction—was termed “zombie formalism” by art critic Walter Robinson. Interior design friendly, jpeg-ready, these canvases were made directly to fill a demand for work that looked like other work owned by rich people. In 2014 and 2015 work by the likes of Lucien Smith and Oscar Murillo saturated art fairs, sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars, and made the news.

Yet the main thing Gayford’s book does is illustrate how influences from this time are everywhere in ways that aren’t reductive, cynical or just plain cannibalistic: ways that only prove painting is alive. When you think of artists who push impasto to the nth degree, you can’t help thinking they couldn’t be doing what they are doing today if it wasn’t for Bomberg, Auerbach and Leon Kossoff. Greats like Richter and the recently deceased Sheila Girling, whose excellent, moving works deserve as much attention as those by her husband Anthony Caro. Conrad Jon Godly’s mountains. Even the almost unbearably bright but arresting Instagram-ready works by Sophie Derrick doff their bubblegum hats to Auerbach’s often dour canvases.

But many of the traits that seem prevalent in the best painting of today seem to derive from the influence of Bacon himself. Gayford presents the artist as a sort of aesthetic anomaly that couldn’t be accounted for, and whose influence revolutionized how proceeding artists would handle paint. He loved the tactility of it. He would use his skin as a palette. He would mix dust from the floor of his chaotic and debauched studio into the pigment to create the texture of clothes.

Like Graham Sutherland he was a proponent of “inventing”: creating things that weren’t there or taking things from a memory bank of images. Only he took this to the extreme, hardly ever painting from models. His Three Studies for Figures at the Base Of a Crucifixion (1944) were, according to the critic John Russell, “images so unrelievedly awful that the mind shut with a snap at the sight of them”. In this invention of something which critics at the time not only thought they hadn’t seen before but which would actively repel them through their unfamiliarity, we recognize an abiding spirit that would shape paint to come. Painters like Neo Rauch and John Currin, who “invent” so much of their figurative works, wouldn’t have been possible, one thinks reading this book, without Bacon interposing himself between the modern day and Hieronymus Bosch. Gayford says art historians describe the work as “painterly”.

In 1946 Bacon came up with the artwork Painting, which shows carcasses, an umbrella-shaded Fascist with half a head and bloodthirsty shark mouth against a pink background. He had originally set out to paint a chimp and a bird of prey. These mental composites formed the basis of his work, and that of painters today. For his first “screaming Pope” 1949’s Head VI, he combined the velvety bust of Velázquez’s Pope Innocent X with the image of a screaming actress in a film still from 1925’s Battleship Potemkin. Now artists like Eric Fischl work from various photographs, sometimes to create one person.

This book tells the story about how the likes of David Hockney, Frank Bowling and Bridget Riley conquered the American scene, and how art by London painters came to break the bank. But the real triumph of the book is the survival of the medium of paint itself. How it has not only adapted and remade itself in the modern day but proven itself capable of taking on a multitude of different approaches during a few decades. It is a survival story, one of victory, and also one of legacy.

Bridget Riley said of the abstract painters who inspired her: “They above all wanted to continue working in this visual medium. So that meant finding out what to do.’” And that’s why paint is still viable. Even over half a century later, painters are still finding out what to do.

Modernists & Mavericks: Bacon, Freud, Hockney & the London Painters

Out now with Thames & Hudson

BUY NOW