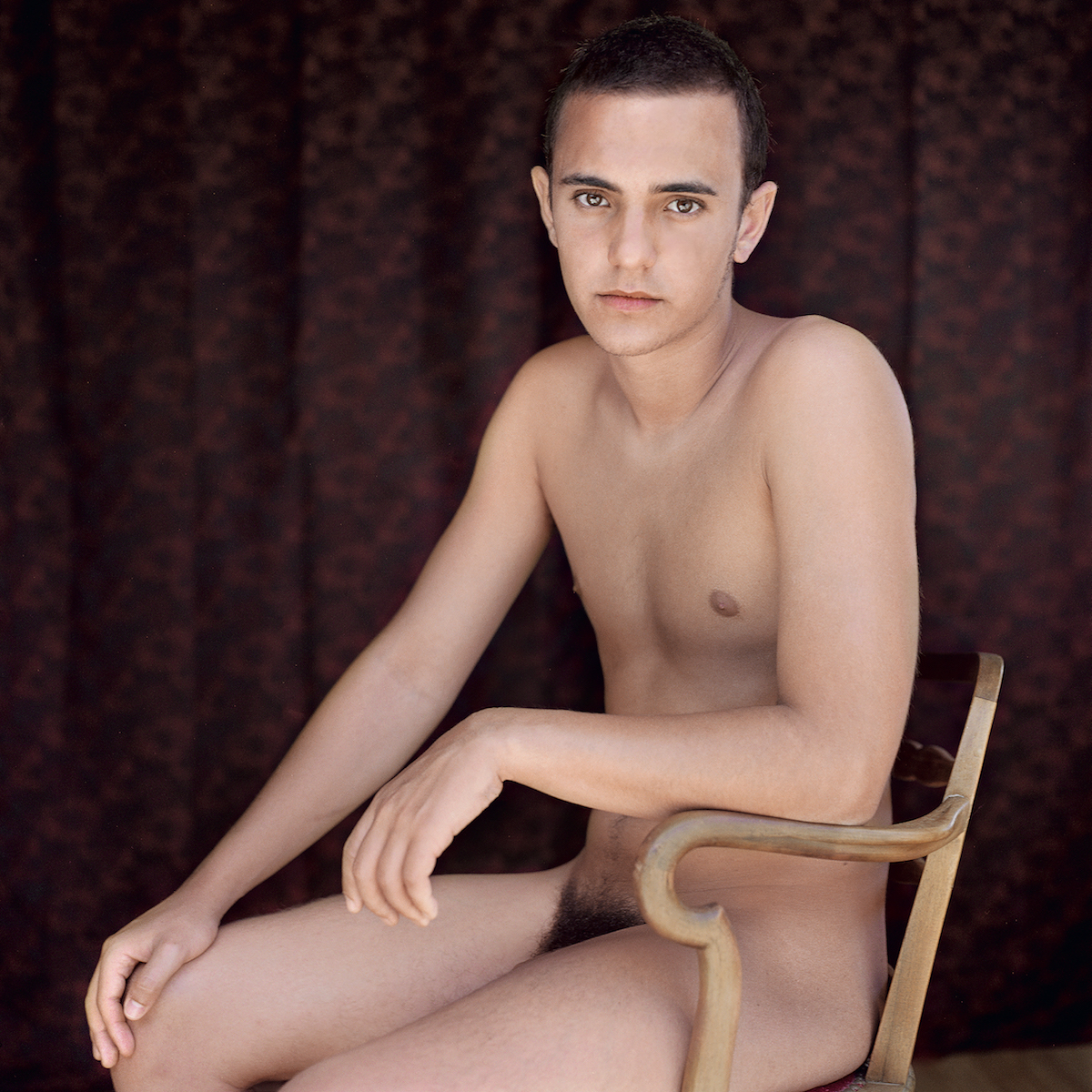

Portrait 37, 2011. © 2021 Mona Kuhn

Like many photographers, Mona Kuhn started out photographing the people closest to her, friends and family at gatherings near her home in Sao Paolo, Brazil. She took her first pictures aged 12, and those initial photographs were personal, unguarded. It was only later that she began to consider the relationship between photographer and subject.

Like many photographers, Kuhn later left her native country in curiosity, migrating first to the US, and later living in Europe. One of her earliest influences though was a fellow Brazilian. Known for his black and white representations of Afro-Brazilian subjects, Mario Cravo Neto was one of Brazil’s preeminent photographic artists. Through his work and later in person, Neto impressed on Kuhn ideas (such as the importance of establishing trust with your subjects) that left an indelible mark on her and her work, in particular her approach to nudes, and the relationships she built with her sitters and muses. Kuhn’s images are often staged in close collaboration with her subjects, and always with their consent: a “creative intimacy” Kuhn says she shares with the people in her pictures that “cannot be easily understood in our suspicious world.”

“Kuhn asks if it is ever possible to desexualise these bodies while also respecting their inherent sexuality”

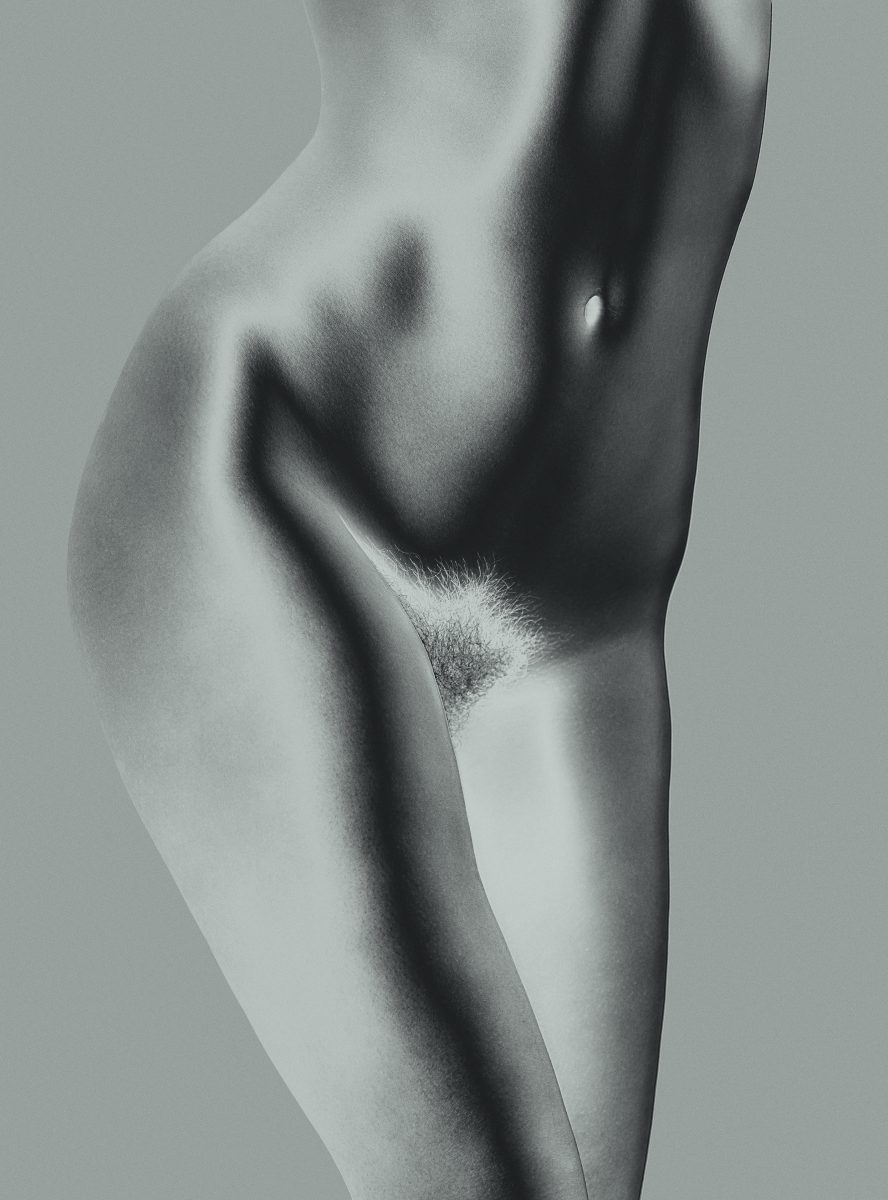

What Kuhn understood from Neto (who died in 2009) was also the difficulty of shooting nude figures: the nude figure is always loaded, especially in the photograph. Kuhn has grappled with the notion of the nude and its meaning for decades, whether shooting communes in Northern California or naturists on the island of Rugen in Germany. In 1995 she visited one of Europe’s oldest naturist communities in France, a place that is closed to the public and has existed since the 1950s. Over the course of eight years working among this community, Kuhn developed one of her most significant works, Evidence (2000-2008). In it, she moves from the black and white of her early works to lush colour, imbued with the warmth of the sun in the south of France, bodies blurring in and out of focus, nubile, preternaturally perfect. Kuhn doesn’t deny the confidence and obvious beauty of the bodies she photographs; she also asks if it is ever possible to desexualise these bodies while respecting their inherent sexuality.

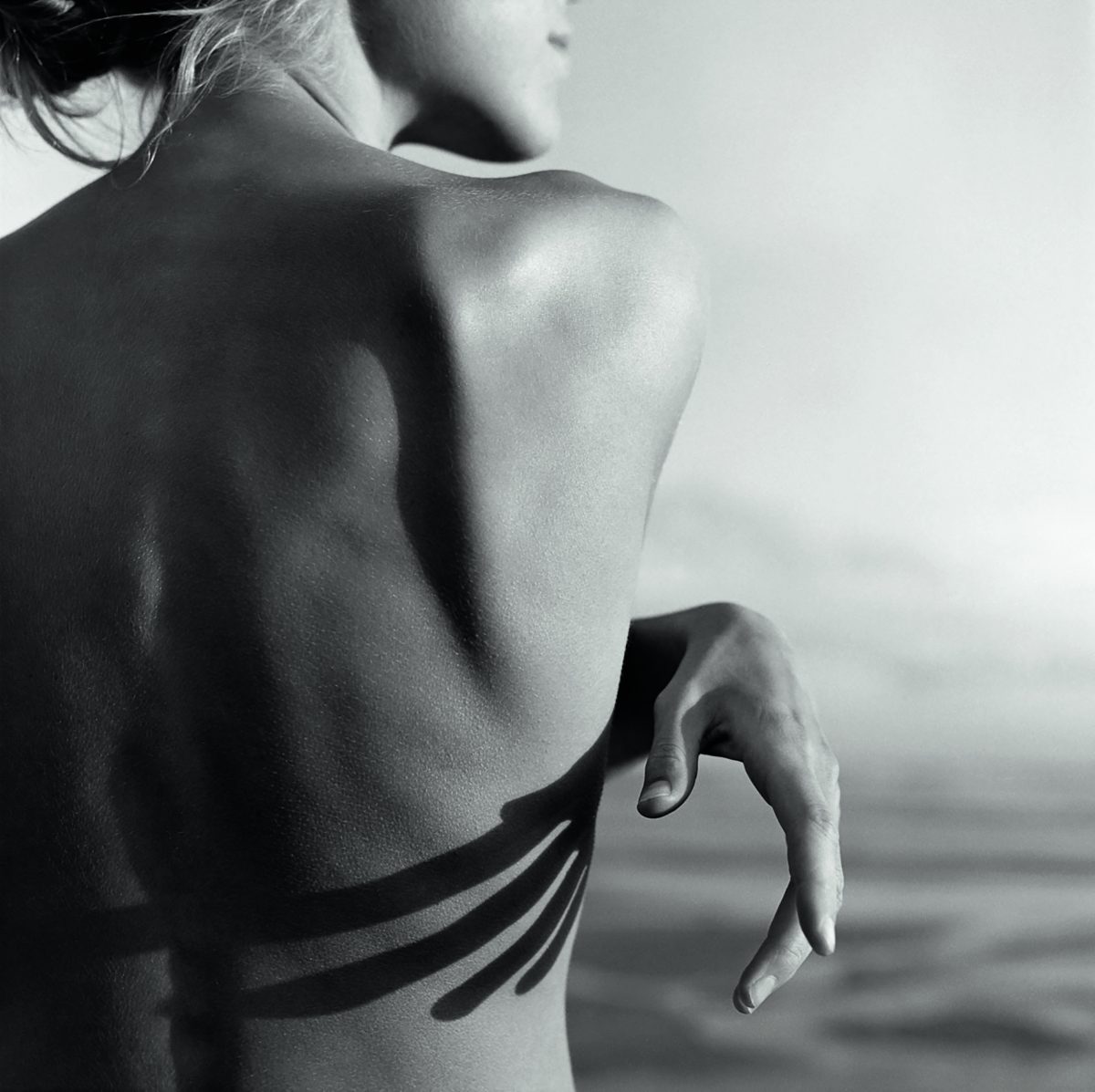

Kuhn’s retrospective book, Work (released in March 2021) is the most significant published collection of her work to date. From those first professional pictures, black-and-white formal studies of bodies that recall Hans Bellmer or Man Ray, Kuhn moves gradually towards a more literal, direct look at the nude and then gravitates slowly towards abstraction, towards obliteration of the figure in space, in a landscape or in architecture, or if not obliteration then a metamorphosis of form. Perhaps, over the years, she wearied of knee-jerk reactions to the nudes, challenging the very limited scope viewers still have for looking at them.

“Photographing anyone in the nude is my attempt to reach that moment of perfect balance,” Kuhn says in an interview with Elizabeth Avedon, included in Work. This is at the crux of Kuhn’s questioning and her gaze: how to achieve perfection in an imperfect world. How to align the mortal figure with nature, to examine bare bodies as we might look at plants: in one series she juxtaposes pubic hair and succulents. Kuhn says she wants to create hope and freedom in a world so full of grief and pain. Her nudes have ultimately become “a proof of our being, our presence in time, and ultimately caring for what will be lost.”