Does money make you a better person? No. Does it make you a better mother? Possibly. I came across one particular blog post on a deep dive into the Internet (in short, I googled “does money make you a better mother?”). The article essentially put parenting down to passing on a “rich” or a “poor” mentality. Rich people don’t follow school schedules, it suggests. They take vacations when they want to and give their children freedom. Then in the midst of this stupid article, something unexpectedly struck a heart chord. Rich parents raise kids to think that being themselves is a great thing to be

.

I grew up in a “poor mentality” family, believing that we were on the breadline. With an immigrant father, the idea that hard work = money = security was drilled into us. At thirteen, I had two jobs: a paper round in the village, and in the summer, picking strawberries on a farm. We were terrified of the farmer and convinced he was a serial killer, but after eight hours of now illegal child labour we earned a tenner, enough to buy a new CD. This “poor mentality” is a second-generation paradox of anxiety: it has driven the fear of money deep into my soul, but I can never feel the supposed security it’s supposed to bring, because I’m too scared of spending and losing the security that I never had in the first place. I happen to have also chosen a poorly paid and highly precarious profession. What is better for my own child: to pretend we are rich or feel the jagged edge of the truth? Money doesn’t buy happiness, but it buys things that are more tangible and easier to achieve. As soon as my daughter will hear the inevitable “we can’t afford it”, she’ll know what economic inequality means.

I have been looking at the photographs of the ninety-five-year-old, still-going-strong Alice Springs (aka June Newton, aka Helmut Newton’s widow) who took portraits of new mothers and their babes. The rich, the famous and often the beautiful, Newton’s subjects were glamourous and monied—Brigitte Nielsen, Princess Caroline, Margot Werts, Mirène Le Floch, Tiziana Zanecla. Yet in Springs’s portraits, their obvious wealth is momentarily threatened by something bigger: life. Their usually effortless, pristine facade is dented by their unruly children, who refuse to act as accessories (in both senses) but behave as actual people with minds of their own. There is a gentle but deliberate irony in Springs’s regard. Motherhood isn’t as picture perfect as perhaps we expect from women this fancy. No matter how wealthy, no matter how perfect you are, Springs’s images suggest, motherhood will balls it up proper.

Still, when I look at these women, I feel a glint of envy. Probably, though Springs humanizes them, equalizes them, after the camera was shuttered up, they were surrounded by a nanny or two. To be a good mother, or at least one who is endowed with ultra levels of kindness and patience, the gift of calm and rational decision-making and the energy to give unbridled attention, to make shapes out of egg-boxes, play peek-a-boo and sing Old MacDonald for hours on end, money is undeniably helpful.

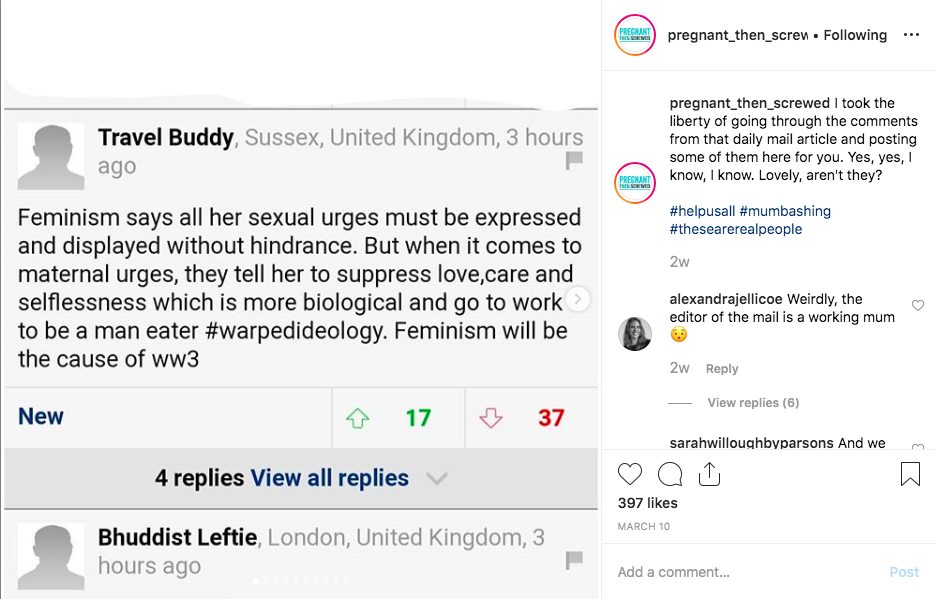

A UCL study of 20,000 families published this month stirred controversy after its findings were publicized all over the media (if you like to be appalled, read the public responses to the coverage on @pregnant_then_screwed’s post). According to the results of a study that began with babies born between 2000 and 2002, “working mothers” are the cause of childhood obesity. To understand what this really means, according to the way it has been presented in the media, the study implicates all mothers (not fathers nor other caregivers) who work, whether full or part-time and particularly, working single-mothers. Their children, the study decries, will be fatter than other children.

What impact does a (very costly) study like this have on actually tackling childhood obesity? Could the money ploughed into this study have been better used to help those families? When healthier foods are more expensive and time-consuming, is there really a fair choice for families under pressure? The study seemed to me to reveal endemic poverty-shaming and maternal stereotyping, wagging a finger at mothers.

“Work enriches us in other ways than cash, and when the lower-earning parent quits their job there is a person bereft of a chunk of their identity”

Money and motherhood remains a sensitive and hushed subject. Income isn’t something that is often disclosed, even among friends and family. I was disappointed by the bit in Maggie Nelson’s otherwise phenomenal book, The Argonauts,

at how she glossed over the money matter, vaguely deflecting her privilege via Joan Didion’s comments on the same: money doesn’t stop suffering. Except sometimes it does, doesn’t it? Surely, in the US, with its hellish health system? Last week my sister WhatsApp’d me a picture that went viral back in 2016: it’s a snap of an itemized medical bill, listing a charge $40 for skin-to-skin contact with a woman’s just-born child following a C-section.

Culturally the topic of earnings is off the table (no wonder it took so long for the pay gap to come out). People are ashamed about how little they make, or how much. There is very little, other than Google averages, to relate to. At thirty-three, I do not own a house, and my gross income for the last tax year was £26,000 (which I was proud of, considering I was on maternity leave for some of it). You can feel alienated and embarrassed when you discover how others live.

Motherhood lands a lot of women, of all ages, backgrounds and classes, in economic hardship. It might not make sense to return to your part-time, averagely-waged job when a part-time, average nursery (if you can get a place) will cost you £1,300 a month (in the UK). If you aren’t able to afford childcare, you have to wait until your child is three years old and entitled to fifteen hours of government-funded hours per week (in other words, not quite two full working days).

I know this strife. I am with my daughter 24/7. Like many hetero couples, as the woman I earn less, so I now work less. We cannot afford to send her to a nanny or nursery in London, where we live at the moment—and where I am still, therefore comparatively “better off”, despite being classified by the Home Office as in poverty. So until my daughter is three, she is with me, all day, every day. I know that this makes me a worse version of myself. I regularly feel rattled, I am forced to pass up work opportunities and miss deadlines. Turning down trips that could get me more experience and enable me to meet important people. I feel abandoned by my childless peers and left behind. I love being with my daughter but I hate the fact that my attention is divided between her and my work, resulting in me being crap to mediocre at both. I know I could, and would, be better, happier, even, if I could buy myself some time.

Work enriches us in other ways than cash, and when the lower-earning parent quits their job—almost always, in a hetero arrangement, the woman—there is a person bereft of a chunk of their identity, ambitions thwarted, professional development stunted.

The new Toronto-based Netflix series, Workin’ Moms, touches on the issue of motherhood and money, but still presents a remarkably unprogressive view (this is evening brain mush aimed at working mothers, after all). The gung-ho, full-time PR exec Kate lands a job that pays more than her partner but sends her to Montreal—six hours away—for three months at a time. At first it seems Kate is going to kill it as she stretches out alone in her new kingsize bed… but then her son gets sick and suddenly, she has apparently walked out on her high-flying role and is back in her role with the family. Ergo, it is impossible to continue to climb the ladder and be a good mother—as her stone-cold bitch of a boss makes clear: it’s us or them.

Workin’ Mums, Ep. 312 – Two Paths, Mike (Victor Webster) and Kate (Catherine Reitman) prepare for their Truair pitches. Photo by Jasper Savage. Air date: Thurs, March 21 at 9 pm (9:30 NT)

Let’s not forget what else money can buy: space. To have a sane and harmonious existence with your loved ones, space, it seems, plays a very important role. In the context of the UK, the amount of space you can have to live in depends on the amount of money you can spend, but also, where you want to live. If you want to live in London, around £2,000 will get you a month’s rent in a flat of around 50 square feet, barely space to swing the proverbial cat. (In Bristol, you could get a three-bedroom house, swing quite a few cats, and in Newcastle a five-bedroom detached property with a garden—swing a whole litter!)

Often it seems that the people who tell you money doesn’t bring happiness are the people who have enough of it to afford the things they need. It’s hard to teach a child there are more important things than money because, right now, what really is more important in the world than money?

I wouldn’t know if being rich would make me a better parent as I’ve only experienced one side of it. I might want to be a rich parent, but do I want a rich child? I think I’d rather send her to the strawberry farm.