At the time of its opening in 2008, The Mosaic Rooms was a rare beast. Situated in what used to be something of a cultural dead zone, the gallery sits on the busy intersection between Earl’s Court and Holland Park, in west London. A few streets away, Leighton House Museum represents many aspects of the legacy of Britain’s relationship with the Middle East region, its Arab Hall an outburst of fervent Orientalism, delighting in the influence of Islamic art on Victorian design. Over the last decade The Mosaic Rooms has offered an intelligent counter to the often-reductive understanding of the Arab world and its cultures in western Europe, left over from colonial relationships and perpetuated by one-note media headlines.

Founded and funded by the AM Qattan Foundation, the gallery was launched as part of a response to “Arab culture becoming totally crushed and overwhelmed by the narratives of political violence and religious ideology that were so prevalent in the media”, according to its chairman, Omar Al-Qattan. If anything, those narratives have become more entrenched in recent years, but a more nuanced response from the art world has started to pose alternative insights. Initiatives like Janet Rady Fine Art and Rose Issa Projects source and represent artists from the Middle East region, and the market for contemporary Arab and Iranian art thrives, consolidated by Christie’s becoming the first heavyweight auction house to launch sales in contemporary Middle Eastern art from new salesrooms in Dubai. The Shubbak and Nour festivals have each injected a diverse showcase of art from the Arab world in London, while the annual Liverpool Arab Arts Festival is now approaching its twentieth year. The V&A Museum launched the Jameel Art Prize focused on Islamic traditions in new art and design, and in 2015 the Whitechapel Gallery in association with the Barjeel Foundation showed a two-year exhibition programme of modern and contemporary Arab art.

“The Mosaic Rooms has offered arguably the most consistent space and voice for contemporary Arab art and culture in London over the last decade,” gallery director Rachael Jarvis tells me. A mosaic builds a picture from composite elements, and the gallery has sought to deliver a finely drawn exploration of a region of vast geographical, historical, linguistic and cultural variety. Often maintaining close relationships beyond their time with the gallery, I find numerous artists who are eager to tell me about the role of The Mosaic Rooms in their practice and development. “My experience at The Mosaic Rooms was fundamental to my art practice. I started a new phase in my work, which is still ongoing. It was there that I found the most profound understanding for my research and my art,” writes Nadia Kaabi Linke, the Berlin-based installation artist of Tunisian and Ukranian heritage. Larissa Sansour, the Palestinian artist who was involved with the Tunisian Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, was also given her first UK solo show at the gallery, tells me, “It is very important to have an institution in London with The Mosaic Rooms’ artistic focus and commitment. My various collaborations with the institution over the years have always been very successful, impeccably facilitated by a dedicated, generous team.”

In recognition of its tenth anniversary, the gallery launched a season of exhibitions and events running from spring 2018 to autumn 2019. Overseen by Jarvis, the programme alternates between three group shows and a series based around influential modernist artists, curated by Morad Montazami. This is not the first time the gallery has built exhibitions purely focused on modern art—in 2015 it showed the first (and only) UK solo exhibition of the renowned Syrian artist Marwan, who died the following year—but this strand represents a new direction. Montazami comments on the reasons for creating exhibitions that challenge canonical notions of art history: “London is considered one of the capitals for post-World War Two cosmopolitanism, where Arab and African artists first travelled to exhibit in European galleries and cultural institutes. In a way [the series] is also a retrospective look at the period when a lot of Arab and African artists became marginalized due to a lack of interest from the Western art world.”

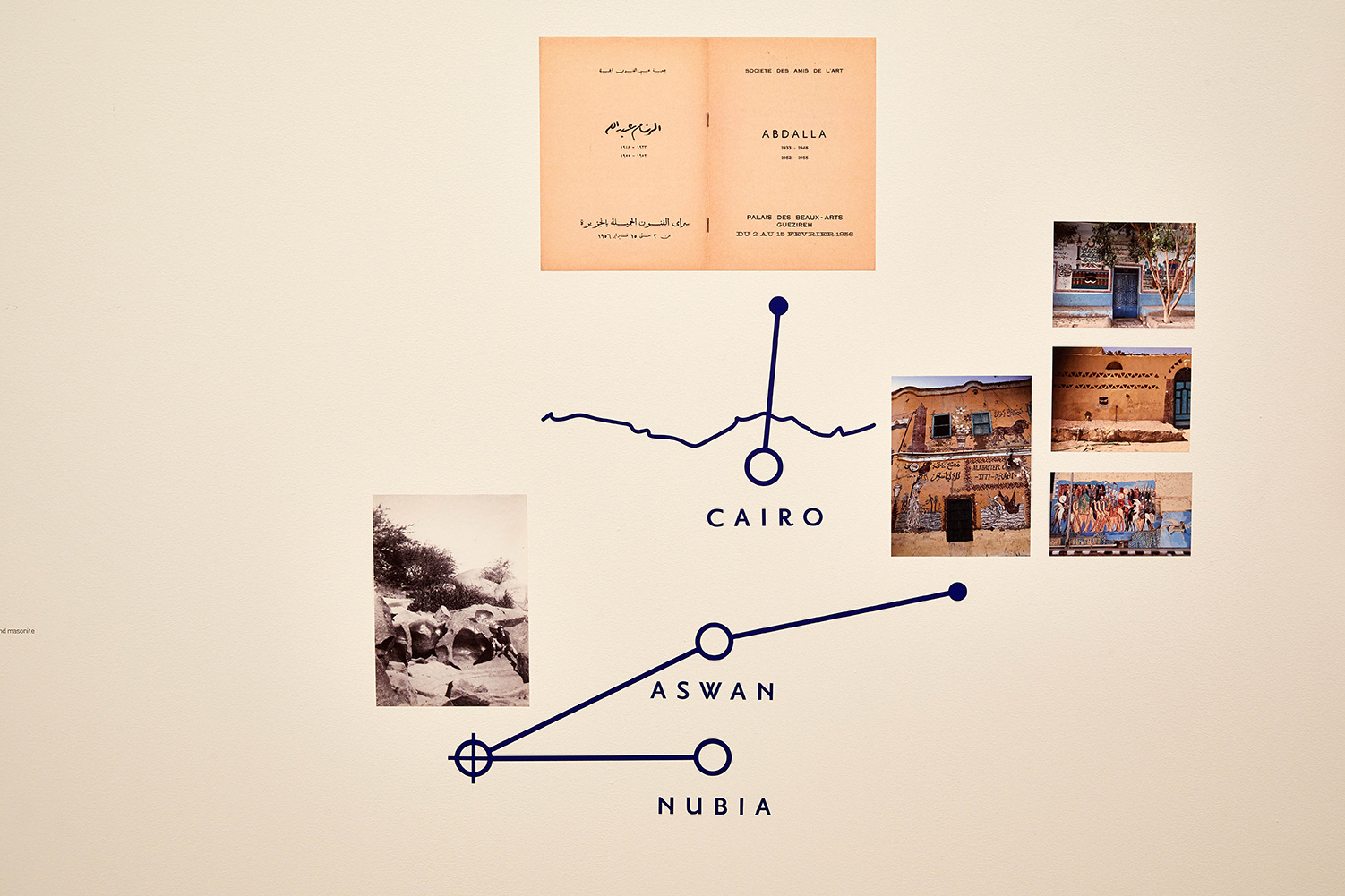

The first show, Arabécédaire, focuses on Hamed Abdalla (1917 – 1985), the prominent Egyptian painter and researcher whose work teases meaning from abstraction through a playful visual approach to words. The exhibition uses paintings alongside previously unseen archive materials, following real and imagined journeys as a way to explore the development of Abdalla’s visual language and political ideas. “I consider Hamed Abdalla the epitome of Arab cosmopolitanism,” Montazami says. “He went beyond the East and West abstract categories to set up a new language of what he called ‘letterist expressionism’ (using the written word as a means to experiment with colour, texture and abstraction). In Abdalla’s paintings and archives, we see a whole underground art history take on a life of its own.”

The anniversary season also looks to consolidate and expand The Mosaic Rooms’ connections beyond the UK: the contemporary strands involve collaborations with external curators and new institutional partnerships. Cairo’s Townhouse Gallery will reflect on its own twenty-year history through a group exhibition in summer 2018, and the Kulte Gallery in Rabat will bring the season to a close in summer 2019. This hugely ambitious programme examines the legacy of Arab modernism, with three promising new shows that offer fresh interpretations of contemporary Arab art and culture through an inquisitive, inclusive gaze.