Osman Can Yerebakan meets with mosie romney and Marcus Jahmal to explore “all the little nuances and the details of everything in unison“.

Fellow artists mosie romney and Marcus Jahmal’s friendship started at first swipe. Once the two began following each other on Instagram in 2018, they noticed inspirations to borrow from each others’ paintings. “We became fans of each other. Everyone posts their work on there but you have to riff through the good and the bad”, Jahmal said. romney was working at the Studio Museum in Harlem and painting at the same time, which prompted Jahmal to consider them as “really motivated to be successful”.

The two New Yorkers met over Zoom in the late summer to discuss their connection, which started online but quickly moved into the analogue universe when romney became Jahmal’s studio assistant. The biggest takeaway for romney was learning how to manage a studio while building a portfolio. “Working with Marcus helped me see the pace of making paintings, having them come and go”, they remembered. “Also, I was doing some correspondence, answering some emails while thinking through my work.”

“In a studio most people can do those jobs of mixing paints and such, but what we were mostly doing was talking in-between work and those conversations were leading to more painting”, Jahmal ruminated on romney’s time at his studio. “That was the major part of our working together.” Perhaps what kept the two artists connected over the years was this deep artist-assistant bond at the studio. “It’s always nice to have someone, especially a person whose opinion you value because this way you can share your ideas back and forth. A push-and-pull conversation is what every artist needs”, he said.

For romney, the experience at their friend’s studio was meditative as much as educational. “I remember smoking weed, looking at a lot of paintings and just talking about symbols and archetypes—and dreams”, reminisced romney: “And Marcus had a dog that would pee and poop everywhere!”

Jahmal, who is self-trained, had found similar rewards from working in other artists’ studios years earlier, especially managerial tips that are not taught in classrooms. “Everyone who went to art school always tells me that they didn’t learn anything about running a studio or how to work with galleries and institutions”, he said.

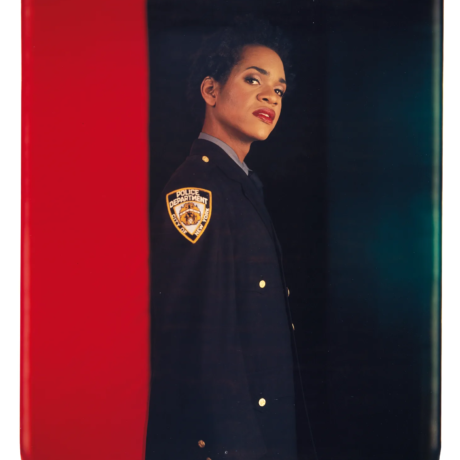

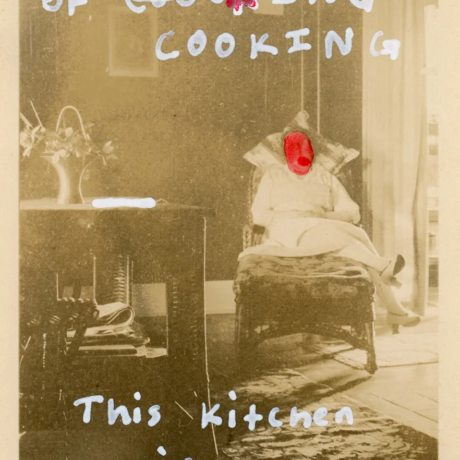

Years later, their catch-up went back to the digital realm, where it all started with a click: romney was in Amsterdam for the Painters Painting Paintings residency with their dog (“I really like Amsterdam a lot; very pleasant and clean!) while Jahmal was at his Bushwick studio. Moreover, stars aligned later this autumn when they both opened solo exhibitions in New York. romney’s first solo show with the iconic downtown gallery PPOW, titled Rhizome St. / Fugue Avenue, features a group of trippy, intergalactic landscapes where dreams and realities overlap. Under a moody red light, the paintings at the Tribeca space feel liquid and cinematic, with narrative juxtapositions that defy a need for explanation. Uptown at Anton Kern Gallery, Jahmal’s paintings in Interiors similarly feast on a plethora of scenarios: similarly operatic, they have more defined frames, alluding to geometry and architecture, with almost masculine finishes. From a matador to a jazz musician, and a mafioso, the figures traverse the fields of logic.

Stemming from the core idea of figuration, the two painters diverge to different routes in their handling of representation—particularly of Black bodies—in this tangible world, as well as history, memories and dreams. They re-unite, however, in a joint commitment to blur the borders of such sources. In Arrival (2023), which consists of oil paint, collage and rhinestone, romney’s perspective hovers above a spiral staircase—a typical dream setting—on which a bird is perched, while a hazy figure climbs up the vertigo-inducing steps with a cigarette in hand. Smoking is also an act depicted in Jahmal’s Gentleman (2023), which shows a dapper man clad in tuxedo with a cigar in his mouth. Dominated by a medley of blue and black hues, the painting’s nocturnal atmosphere is completed by a massive upside-down bat. The works ideally represent each artist’s narratively liberated and technically determined lexicons.

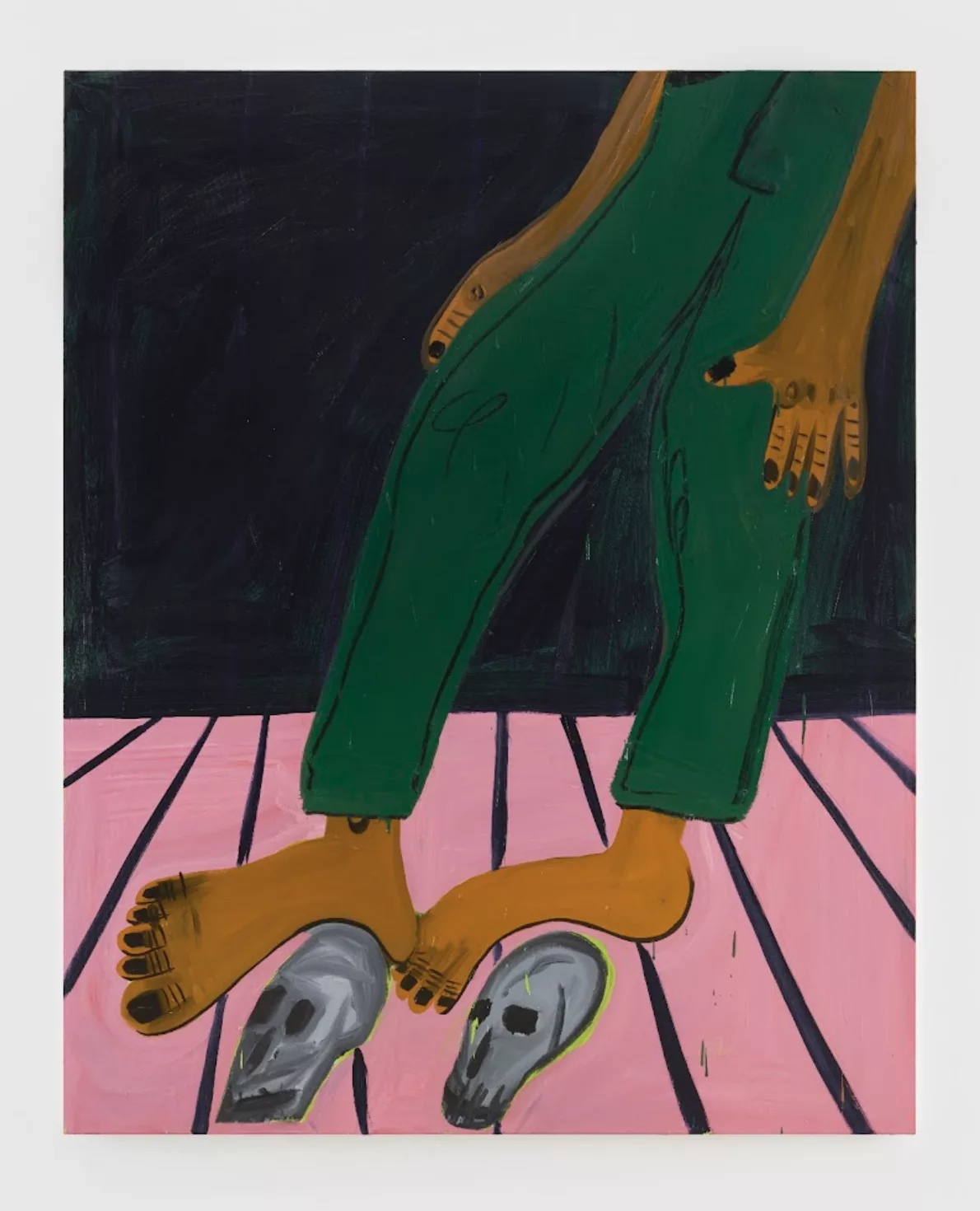

Four years apart in age (romney is 29 and Jahmal, 33), the millennials process the abundant visual stimuli surrounding their everyday existence with uncompromisingly subjective filters. Their figures inhabit personalised landscapes, concocted with determinedly unburdened brushstrokes. “I think the blurriness is reminiscent of fog, or the void, performance, unreality kicking up the sand, and the subconscious”, romney mused. “Also speed or slowness in the painting create this blurriness or fogginess.” Movement is tangible in some of Jahmal’s works, “but others are stagnant”, he said, “I’m really more concerned about colour and composition, with some symbology and certain placements in the work—figures are more arbitrary for me.”

romney avoids calling their subjects “bodies”, because “for some reason this just feels more comfortable to me”. Jahmal agrees with his friend in this word choice and considers his figures as tools to “propel the viewer to look at the whole picture plane with all the little nuances and the details of everything in unison”.

The duo’s friendship overlapped professionally when Jahmal included romney in a group show he had curated at Almine Rech’s London scape, titled Different Strokes, in 2021, along with colleagues such as Spencer Sweeney, Stanley Whitney, Huma Bhabha, Peter Saul, Katherine Bradford. “I remember showing two large-scale paintings”, romney said, “but more interestingly, one of them was purchased by the collector Edwin Oostmeijer who in fact invited me to this residency in Amsterdam”.

Osman Can Yerebakan: Let’s start with your particular approaches to memory, and even time. This isn’t necessarily as a lived experience or a linear passage of time, but more about things being remembered and internalised.

mosie romney: For me, experience really does create a lot of the narrative. I currently have paintings that include a canal system of Amsterdam. It didn’t occur to me that my pattern was mimicking the system until I was looking at the map, and I realised “Oh, this looks like my painting.” Or I can see a show with stone lions in it and soon afterwards I take these images of the stone lions and recreate a composition that fits my story. Compositions definitely tend to start with experience. For example, I have screenshots of movies that I’ve watched, or photos of myself that other people have taken—they help me build the narrative. In terms of time, this is very important, first in terms of when the painting happened but also when the experience that has been transformed into a painting happened. Also, there’s the speed of the market. People want you to paint really quickly and bust things out fast. I’m trying to work against that and take my time and acknowledge my presence.

Marcus Jahmal: We jump into the real world and we have to learn very quickly. We take our bruises in the beginning. Different people take advantage of you because they know you’re pretty new and green and fresh. “Oh, you have 25 paintings? Give us all 25 for a show!” When you realise maybe you should hold back a little, you start becoming more selective about what to give or hold. This also made me think about timelessness and the trends. This is something that I think mosie and I both share and connect on. We have an affinity for art history—I don’t know if I could speak for you too mosie, but this is what I think at least—we want to be painters, and not let our race or gender or sexuality sit in front of the work. We instead focus on making good work and on the fundamental elements of how a painting thrives, whether it’s colour, gesture or composition. When it comes to time, I think that painting is a way to time travel. Painting offers multisided experiences, let’s say of being in Europe, or being in interesting places that are not New York. As artists, we take in a bunch of things and first let them sit in our psyche for a bit. Later we regurgitate them all back out onto the canvas, mostly moving through time in a nonlinear way. This of course means recalling memories and experiences that might have happened months or years ago. A lot of times I’ve noticed that I’m creating scenes and things from my imagination, especially of interiors, and later I’ll find myself in that space in the future. An Airbnb in Rome, for example, will have a ladder on the wall as part of the decoration. “Wait a minute—I painted something exactly like this a few years ago!” You can move forward in time and also be present.

mr: I disagree a little bit with something that you’ve just said: I do think that painting for me is very much about timelessness, but also my race and my gender play a big part in my experience. I think my decision to not to change my composition and my figures all the time is a symptom of being non-binary. Having the colours of my figures shift is a connection to my Blackness because in colour theory, black is the amalgamation of all colours.

MR: Of course, I didn’t mean to say these elements aren’t present. With us Black people, regardless of what we do, of course this experience is going to be a part of the work. I was just talking about playing into trends and marketability. I don’t like letting these overshadow the skill that you want to put into the painting. I don’t mean painting white figures or something like that. I just mean that this doesn’t sit on the forefront of my mind when I’m making work.

mr: Yes, it just is.

MJ: Yes, I don’t think white painters sit around and plan to paint white figures. I want to have freedom in a way that liberates me.

OCY: How about the scenarios you put your figures in? Some of them look surreal and in others, narratives are more clear. I’m thinking about what Marcus said about the Airbnb in Rome for example. How do you let your figures occupy the canvas and the space they’re in, both physically and psychologically?

mr: My process always starts with washes of colour and projecting. I use a lot of laser projection in my practice, mostly to put down a composition and less for detail—the details end up being more where the imagination and painterliness come in for me. They always sit in abstraction and in not having a place, and then I build a life around the figures.

MJ: A lot of it has to do with the format that I’m working on: the size and the shape of the canvas, whether it’s a square or a rectangle, or if the canvas is a landscape or horizontal. This informs what I’m going to do next. Sometimes my figures can be cropped, so they won’t fill up the whole picture plane. Also, this is about the feeling that I’m trying to get across with a particular figure, the emotion that they’re depicting to transfer onto the viewer. The psychological part of it is about things coming from my psyche, a myriad of motifs that I repeat all the time. Other people might not understand them, but I like my figures to be almost universal in a way, so the viewers can have their own interpretation.

mr: Also, psychologically, I have trouble recounting my dreams, and I feel like my paintings end up being the dreams for me. I actually look a lot into Carl Jung‘s interpretations of dreams to get an understanding of my paintings. I think that’s where the psychological and the canvas intersect a little bit.

MJ: What you just said is true for me, too. I pay attention to dreams as well, but they’re always in fragments, such as a cat or a doorway. Maybe it’s about completing the picture, adding the colour or completing a task through dreams.

mr: Yes, I find myself drawn to painting things I like, such as suits of armour. Maybe I’m feeling vulnerable or needing protection—maybe the subconscious leads me to something, but the understanding comes a little bit afterwards.

MJ: I sometimes paint umbrellas or other hovering things like curtains. Obscurity covers the painting in a way. Making work is really cathartic.

OCY: Maybe you can explain more deeply about the subconscious. Let’s talk more about this open-ended side of the work and things being liquid and malleable.

mr: Unreality is really important, as well as fantasy. They’re a symptom of my neurodivergence. I try to make meaning through symbolic order and it doesn’t have to make sense. We try to apply meaning to a number of things, and then we have this imaginary system of money through capitalism, but there’s a lot of unreality. This is something that I’m grappling with and feel comfortable exploring.

MJ: I agree with that. We turn on the news and see that the world has flipped upside down. It’s always been so, but it’s more prevalent than ever now. The world is in a wacky place. Work is one of the only places where you can grapple with and oppose that. I’m not going to say that the things that I paint are realer than real life, but they can be just as real. Artists can make the world a better place—imagery controls the world. Movies we watch can predict the future, whether it’s positive or scary. Artists have the power to reclaim that imagery and put it in a more noble place.

mr: I’m also thinking about Giotto, and how important the image was to convey biblical stories and to get messages across. I think that painting and the image can convey the restlessness and unreality of today.

OCY: Speaking about restlessness, I wanted to ask you about mobility, specifically travel. How does seeing other realities, architectures, ways of being influence your work?

mr: Experiences, travelling and seeing other places and other dimensions are really important to keep the work fresh. Too much of a good thing or being comfortable is not fun in the long run. Mobility is important in my practice as a human being: going, seeking, wandering and moving around. Not doing the same thing is important, and not committing to one kind of style or technique for too long feels like an embodiment of mobility.

MJ: As artists, we have to be mobile. How many paintings can you make by sitting down in one place? We have to take in new experiences, which I think is what people expect from us. Not everyone is able to do that in this capitalist world—a lot of people have jobs nine to five that lock them down. Travelling and putting your experiences into the work is also being generous to the viewers because they can also vicariously travel through these experiences and perspectives. Speaking of architecture, I’m thinking of the metal work I came across in France. I think both mosie and I have used that motif at some point. I did research on those particular motifs and found out slaves used to make their iron shackles for their ankles but also create the iron works on those gates. This French gate work started over there, but then it travelled over here to New Orleans when the French conquered there and probably moved to Brooklyn where I was born and raised.

mr: Also, mobility allows for different perspectives. I was obsessed with painting pigs for a while, which led me to look into what pigs mean in America versus what they mean to people in other cultures. Here, to some people pigs are cops and then in Eastern cultures, pigs are a symbol of abundance. Gathering these varied meanings for symbols and archetypes is an interesting way to build up the work.

OCY: Finally, I wanted to ask you about how you build your colour palette. Marcus, I see that you assign a specific colour to different figures and archetypes, and with you mosie, everything is more blurry.

mr: I have a little colour list and each colour means something different—sometimes a few different things. Lavender is gay or love or God. Blue is the ocean, sadness or its ancestral. And yellow is an emoji or the sun. I think about iridescence a lot, colours fading into each other and how they vibrate. The edges between colours are really something in terms of transition and shift. And contrast is very important. I make a lot of my own black with blue and brown, but I’ve also started using black just from the tube to get the truest absence of light. That is a great way to build contrast and bring the viewer in.

MJ: I’m interested in colour theory and making it a cathartic experience in the studio. I mostly use paint out of the tube and I mix here and there to create tones. As opposed to being solely concerned with one work, I’m concerned with the whole body of work and how they all balance each other with colour, especially if I’m working for a show. I’m basically transferring this experience that I’m having, or however I’m feeling emotionally at the time, to the viewer. I think that one colour activates another colour. So that’s why in my work you see more blocking, which is an homage to Abstract Expressionists of New York, to people like Stanley Whitney, who’s still doing that today. He talks a lot about how one colour calls for another colour. Josef Albers said the same thing: that one colour doesn’t mean anything without another one.

mr: I also think silver is a very important colour or pigment in my work, just for self reflection, perhaps like a mirror.

MJ: I started out using oil paint in my first show at CANADA gallery in 2016. I then realised that it was too complicated and switched to acrylic. I just felt I could work much faster, but then I saw mosie using oil. That made me miss using oil. I re-started using it and have been using it ever since. Now I can’t go back—I’m totally enthralled because I went through all the mistakes and everything—the sinking problem and the cracks—I’ve gone through it all. I never have to deal with those with acrylic, but hey, we learn from our mistakes and now I know how not to make them anymore.

Osman: Any last notes before we wrap up?

mr: One thing that I wanted to add is about us getting to know each other’s work and each other as people. One time, Marcus told me my paintings are really happy. I remember thinking that wasn’t what I want people to see when they see my work. That made me think there was something inauthentic about how I’m presenting, because happiness is not my go-to emotion. I remember writing in my journal about how I want the work to feel more true to how I feel, how my spirit feels, so thank you!

MJ: I wouldn’t say that about your work right now, so I think that you achieved that goal! I feel the same when people say my work is dark. I do tend to gravitate towards darker stuff, but the colours brighten the work up. I did a series of tank paintings, for example, and I can see their association with our history, with war. When I was over in Berlin back in 2017, I was at this bar called Paris Bar, which has artists’ works on the walls, like Sarah Lucas. A dealer brought me there and said they ask all of their artists that they bring there do a napkin drawing, so I did one that was a tank. Everyone thought this was because we were in Germany and the first thing that comes to mind is World War II. I noticed that in different parts of the world people perceive things very differently. Over here in the US, the reason why I like the tank imagery is basically because it has a myriad of shapes, rectangles, squares and circles. What people may perceive to be dark isn’t necessarily so in the artist’s mind.

Written by Osman Can Yerebakan