Lydia Eliza Trail speaks with Stanislava Kovalčíková about the complex and unsettling play between conventional figuration and unconscious desire, the problems with curatorial intervention, and the suffocating nostalgia of the upholstery of the Northern line seats.

Looking at Stanislava Kovalčíková’s works, one notices a ubiquitous darkness in her paint, the mannequin, found hair, pigment, all of it. Her obsession with the id — what Freud labels as the unconscious source of all innate needs, impulses and desires — is a mischievous guiding principle in her figurative works. In 2023, the artist presented a solo show, Grotto, at the Belvedere Museum Wein. The large-scale works in the exhibition, heavy with art historicity, have been described as tragicomic depictions of Dionysian debauchery. Formally, these paintings do not lean toward unbridled chaos so much as they deliberately confuse the eye. A graceful nude will sit beside a visage of discomforting unknowability; I thought of the infamous Dream Man when looking at Stanislava’s faces. Here lies the artist’s craft — an increasingly rare quality — to render figuration without cliché or repetition.

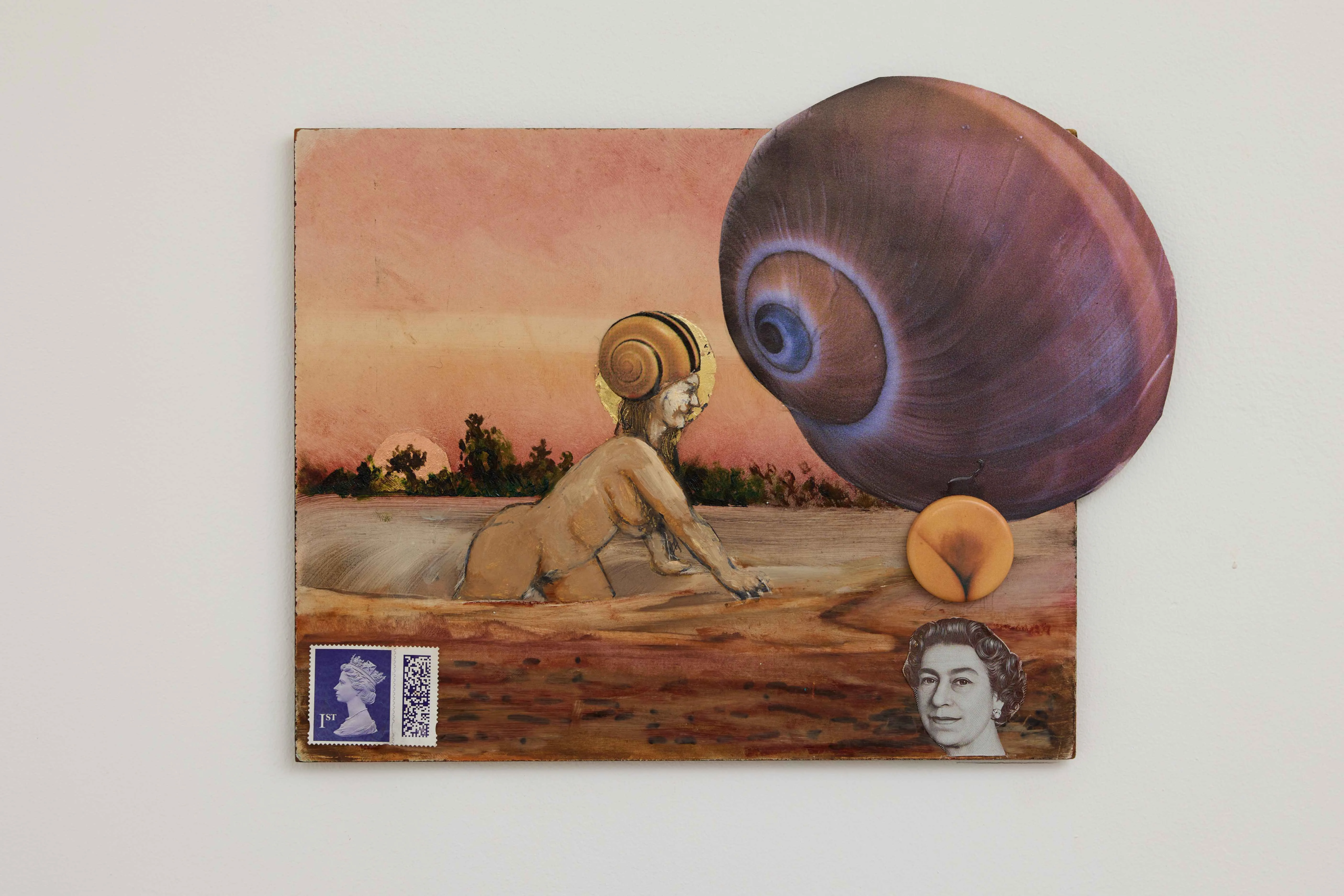

In November 2024, Emalin announced its representation of Stanislava, hosting the artist’s first solo show with the gallery, ret rie vers. The show incorporated a tripartite, split-level install of a series of paintings on 19th-century Prussian clock dials within a fully carpeted space. Two sculptural works, including mannequins, also featured in the show: Kranke Frau (the “sick woman,” 2016–2024) — an homage to Isa Genzken — and Setter (2024), a quotation of Uccelo’s The Flood.

ret rie vers was filled with morbidity. Stanislava chose time and its relentless progression as her subject; time as an imperial device, time as constraint, time as liberator, time as the metaphysical subject that guides our perception of physical space. Clock faces were painted with phantoms whose presence moved away from the bacchanal and Dionysian, toward the moral archetype, the figure of judgement and, above all, mortality. The show’s title, ret rie vers — or Retriever — is named after the dog breed and it’s skill in cornering prey, catching it, and bringing it back to its master. Stanislava meditates on time as master, on herself as prey, and on her work as an act of retrieval.

I spoke to Stanislava about the relative merits and pitfalls of the “install” in contemporary European institutional practice and the current war against the white cube curatorial style. ret rie vers is a testament to the artist’s years of collaboration via group shows and her interest in curation as praxis.

Lydia Eliza Trail: You had a solo show at Emalin this past autumn whose installation was expansive across three floors. How was the process of installing it? You had an artist helper in Tom Hardwick-Allan.

Stanislava Kovalčíková: This show was a new thing. The space is small. I couldn’t be sure it would work up until the last minute. I’m lucky to have a number of artistic friends who are authentic and trying to make something work that’s not necessarily a formula. Tom and I are fans of each other’s work, I think he is a fantastic artist. Sometimes, I do collabs with other artists, and with Tom, we did a show together in 2023, Halbe Sachen, at Galerie Khoshbakht, in Cologne. There, we covered the gallery walls in foam.

LET: Can I ask you about another show from 2023, Cadavre Exquis or The Voluptuous Decay of The Shivering Veil at Braunsfelder? It was a group show that featured some of the greatest artists, in my opinion, of all time: Hans Bellmer, Félicien Rops, Linder Sterling, Soshiro Matubara… the list goes on. Were these artists muses of yours? How did it feel to curate them together for this show?

SK: First of all, it was the living artists, Soshiro and Kazuma, who made me realise that what we were going after in our work — it was something that many others had done before. Felicien Rops’s work in the show is from my collection. It is the first piece of art I ever bought when I made money. Some of those pieces were so hard to get — and it was incredible when collectors decided to support us through lending.

For so long in the German art world, there was a formula for exhibiting — people loved the formula. That is now changing. I see how installations have become popularised. For example, recently, I saw the Merdardo Rosso show at Mumok in Vienna. I think what is important is when directors invite artists to present other artists’s installations.

LET: Do you think that it’s problematic when curators try to use work to serve their own agenda? What if the shows are collaborative?

SK: Yeah. Not their agenda but their artistic idea. It might work in rare cases. But in ninety-nine percent of cases, as an artist, you just think — urgh.

LET: Emalin’s new space, The Clerk’s House, is the oldest building in Shoreditch. It was once a watchhouse for body snatchers during East London’s Jack The Ripper years. It feels like a house inside, preserved since 1735, essentially. How did you decide to upholster almost the entire space? Did you intend this to feel domestic, warm, or off-putting?

SK: The carpet was an early decision; it’s based on a TfL upholstery design. At this early stage, I was thinking about tunnels, especially about how they built the London underground system. A retriever is a breed of dog trained to find prey. That’s their prime purpose. ret rie vers is about finding the easiest way to something: something dead, doomed, the prey. The mentality of a retriever is effectively a metaphor for my way of working. I was sick last year, so it hasn’t been easy to paint the way I usually do. This was a great opportunity, and the title ret rie vers — or “Retrievers” — was about retrieving my own power, in a way. The act of retrieving became a metaphor for my way of working.

LET: Was the separation across the three floors lateral? How did it correlate to the tripartite title: ret rie vers.

SK: The show is tripartite because of the clocks being divided into thirds. I wanted it to be evenly separate: third, third, third. My mind is the retriever, and prey is everything. The house was the prey. But in a way, it reversed, and I became the prey of the house.

LET: I saw that in the show. It was all-encompassing in a way — as if it was the contents of someone’s mind. The carpet, too, was suffocating, both in appearance — it’s geometry and garishness — and its intense nostalgia. You don’t see those colour fields around too much anymore.

SK: Ten years ago, when I lived in London, I did an exchange at the RA. I used to take the Northern line, which had this pattern on it. I remembered how the colours of the people inside would change as soon as they got out of the train. So, I wanted to use this trick with the carpet.

Misha Black was the guy who had it commissioned. It was actually created by a Jewish designer who fled Nazi Germany — she was part of Bauhaus. Something in the Bauhaus colours is very tied to my work, even if it is not visible — for example, in the green of the tabletop in the sculpture Setter. That sculpture is lifted from Uccello’s The Flood (1447), which forms part of his huge Scenes from the Life of Noah in Florence. I made sculptures to try to understand the movement of that piece. There is another figure, which did not make it into the exhibit, based upon the figure in The Flood with a black and white ring around his neck. These figures are something out of a dream.

LET: It reminds me of this Tintoretto painting, Finding the Body of Saint Mark (1555–1556). It has a similar dream-like effect.

SK: I haven’t thought about it, but that feeling was exactly what I was going for with the virtual universe. It’s something like a tunnel, but a tunnel as a metaphysical space and a wormhole. Something appears on the other side, and it’s gone… long gone.

LET: What is that feeling? The idea of a tunnel as a metaphysical space with these images, these icons at the end? There was a peephole at the beginning of the show — a wall of carpet blocked out the shop window with a small hole at its centre, through which you could view the show.

SK: It’s almost as if the painting moves your brain through it. I don’t want to move my brain when I look at the painting; I want the painting to move my brain.

LET: The clock face is dynamic; how do you find painting on their surface?

SK: Clocks help you create an illusion of time. If we just had an hourglass, our perception of time today would be different. Time is so subjective. These clocks were chosen for their specificity of form — they are very Prussian. In the beginning, painting them felt like desecration.

When the Prussians conquered Polish lands, they had a significant population of people they wanted to make Prussian within one generation, and they were successful at it. So, the clocks come around the same time as imposed general education. Poland is a Catholic country, and Catholic clocks are slightly different — the Prussians invented a formula for time-telling that was applied to the Polish population. These clocks emerged at the same time that Germany laid the grounds for becoming an industrial superpower.

LET: In the work Who Would Like to Win at a Losers Game (2024), the numerals of the clock face — which, as you mention, is a kind of imperial time-telling device — have been replaced by these images.

SK: The clock was used to make a lot of people understand a simple thing. It actually robs them, because they see things that they maybe shouldn’t know. That’s the invention of modernity. So the work, it’s a race. It is so human to invent clocks, time, and industries. I don’t think there is another creature who could come up with this.

LET: What are the figures on the clock face racing toward?

SK: Nothing. It’s like an endless circle. A race isn’t something I’m critical of, but I’m not a friend of it. It’s a piece about comparison. The lungs in this work reference Rebecca Horn’s lung work; she spent two years in a sanatorium curing her lungs — I read a story about her lung poisoning, and it was similar to my own health problems. I used to source secondhand pigments because I loved the life they had. But – I was not cautious with their toxicity. So Horn’s lung piece, the performance, is kind of about how toxic it can get — being an artist.

LET: What about the evaporating figure? He reminds me of the Uccello piece because he is kind of palpitating between being and not being.

SK: This guy evaporating is an image of an Israeli who set himself on fire as a protest against the war and the strategy of the military. You know, self-annihilation as a form of protest is deeply disturbing; that is why it’s so good for me, as a painter, to think about it. I have a lot of people who died of their own will from very early on, and I think this was the theme of retrievers.

I study Hindu texts now, and there is one that says people who commit suicide have probably committed it like 200 times, and they’re trapped in a circle. It’s such an interesting idea to imagine that you never kill yourself once. It’s not a single death. It’s always cyclical.

LET: And the hand? The pointing hand appears in many of your work.

SK: I still don’t know who the hand is. You know, if it gives me a hand, I use the hand. It’s some kind of pinpointing. I suppose it’s sort of a superego — or maybe it is the id masquerading as an ego.

LET: Regarding your mannequin pieces in ret rie vers, you’ve mentioned before that Kranke Frau (2016–2024) is a tribute to Iza Genzken. I’ve always loved seeing a mannequin or a doll’s house.

SK: The Isa piece? Yeah, I think three or four years ago, there was a big Genzken wave again. I always found her battle with mental illness inspiring. She is also my daughter’s favourite artist. – she loved Iza when she was like, six or seven, you know.

This is something that’s always interested me to install, the mannequin. And doll’s houses. I think we are all children, and when you grow up, you just become a mannequin.

The artist Bruno Pelassy also inspired me. He uses a lot of brittle hair or used fur. There is something so tragic in it, but funny at the same time. Someone recently described the colour in my works as moth colours. I think that was so apt – I would call them muddy pastels.

LET: The moth comparison makes sense. Your colours and brushwork remind me of when you crush a moth underhand. When I was younger I would try and catch them, but they are so fragile; if you hold them in your hand, the dust that comes off is this dark, muddy colour. If you smudged that on paper, you’d achieve the colour of your painted works.

SK: The softness is an echo of my brushwork. I know when I paint well, it’s very soft and suffocating, almost. I like the description because, you know, the moth goes to the light. Insects just follow their id — so that kind of experimenting with the id is what I’m trying to do.

LET: ret rie vers was all-encompassing as an exhibition. To be in it felt like being swallowed, immersed in someone else’s person — your personhood.

SK: I wouldn’t call myself an installation artist. I make these rooms out of my love for the work. Everyone does installs now, even museum directors. You don’t have to study to be an artist, in my view, but when you’re busy cutting through the fabric of society, and then you come up with an installation, it’s scary. It’s similar to the feeling you have when looking at AI creating images, right?

LET: What do you mean by an install? As in, the antithesis of the white cube? Do you think that’s what will come to dominate curatorial practice next?

SK: It’s what the art world is fighting right now, what comes after the white cube space? Oftentimes, it is these vintage, lived-through urban spaces. I like it until it becomes a formula. I am trying to become less and less elaborate in my installations, so it’s almost found, but not like found on Etsy. For example, Tolia Astakhishvili is fighting similar demons; she’s a genius who creates spaces with her friends, like The First Finger (Chapter II) in Berlin. Actually, every artist I know who matters is fighting similar demons at the moment.

The white cube solved some things, but whatever comes out of this new wave will shape curation for the next forty years, if not longer. Artists are an endangered species. Somehow, they create the capitalistic thing, but they are also the first victim.

Words by Lydia Eliza Trail