Last weekend the clocks changed. For many, this meant an extra hour lolling luxuriantly in bed on a Sunday. Sadly, baby didn’t get the memo about daylight saving, so for me (and I imagine most parents of young children) this meant a tea party with a one-eyed, thirty-year-old stuffed cat and a suspect-looking rabbit wearing a blue waistcoat at 5 am. There was a deep, pitch darkness outside; the traffic was still sporadic and distant. The creak of floorboards in the hall had a hopeful timbre—maybe someone else was awake out there?

Clocks symbolize, obviously, time—something I have a very different relationship to now I am a parent. For the first six months we counted baby’s life day by day, then week by week, and now, month by month; watching her muster more strength and become more secure in the world. Watching time made it seem, to me, to be moving slower than ever. I began to feel time again as it felt when I was a child myself, long, never-ending. A baby, of course, has no real concept of time at all—another of the reasons for their blissful Buddha-like state, no doubt.

Christian Marclay, from the video installation The Clock. Courtesy of the artist

Christian Marclay’s The Clock, the twenty-four-hour film compilation of clocks from cinema that debuted at White Cube in 2010, is back in London at Tate Modern, where it is screening until January, (with the next and final twenty-four-hour straight marathon happening on 1 December). I find The Clock indulgent and maddening. It is not, Marclay says, specifically a work about time, but it reflects time, and it demands time. Marclay wants us to be more patient—to slow down—a motive echoed by many other artists of Generation X. Why? As Marclay’s film itself shows, time flows and goes, of its own accord.

I have similar contempt for another work: Tehching Hsieh’s One-Year performance, 1980-1981. The Taiwanese-artist shut himself in his Manhattan studio and punched a clock, once an hour, every hour, for a year. The work was dubbed “seminal”, and his act “extraordinary”, pushing the boundaries—Hsieh wanted to investigate, he said, the “nature of time”. I recently met a mother whose baby woke every forty-five minutes, for months on end. Presumably, Hsieh did not need to breastfeed and do the ironing in the hour between his self-imposed clock punching. If he’d spoken to a parent, he would have learned plenty about the nature of time, without all that effort.

With a child, you don’t need to watch twenty-four hours of clock age to meditate on the meaning of time, to feel its pace. Before baby, when time was one vast, fast-moving swathe, from which a million procrastinations could be unfurled, The Clock and One-Year Performance made more sense to me. Now, days are divided up in a regimented fashion, and time is constantly on my mind. It’s something I observe day to day, week to week, month to month—there are milestones to keep a check on, measurements to be taken, a timetable of snacks and naps to adhere to. You need to be on time for appointments and you need to leave on time to make sure it all runs—like clockwork. Time is now the difference between serenity and a meltdown (usually for us, not baby).

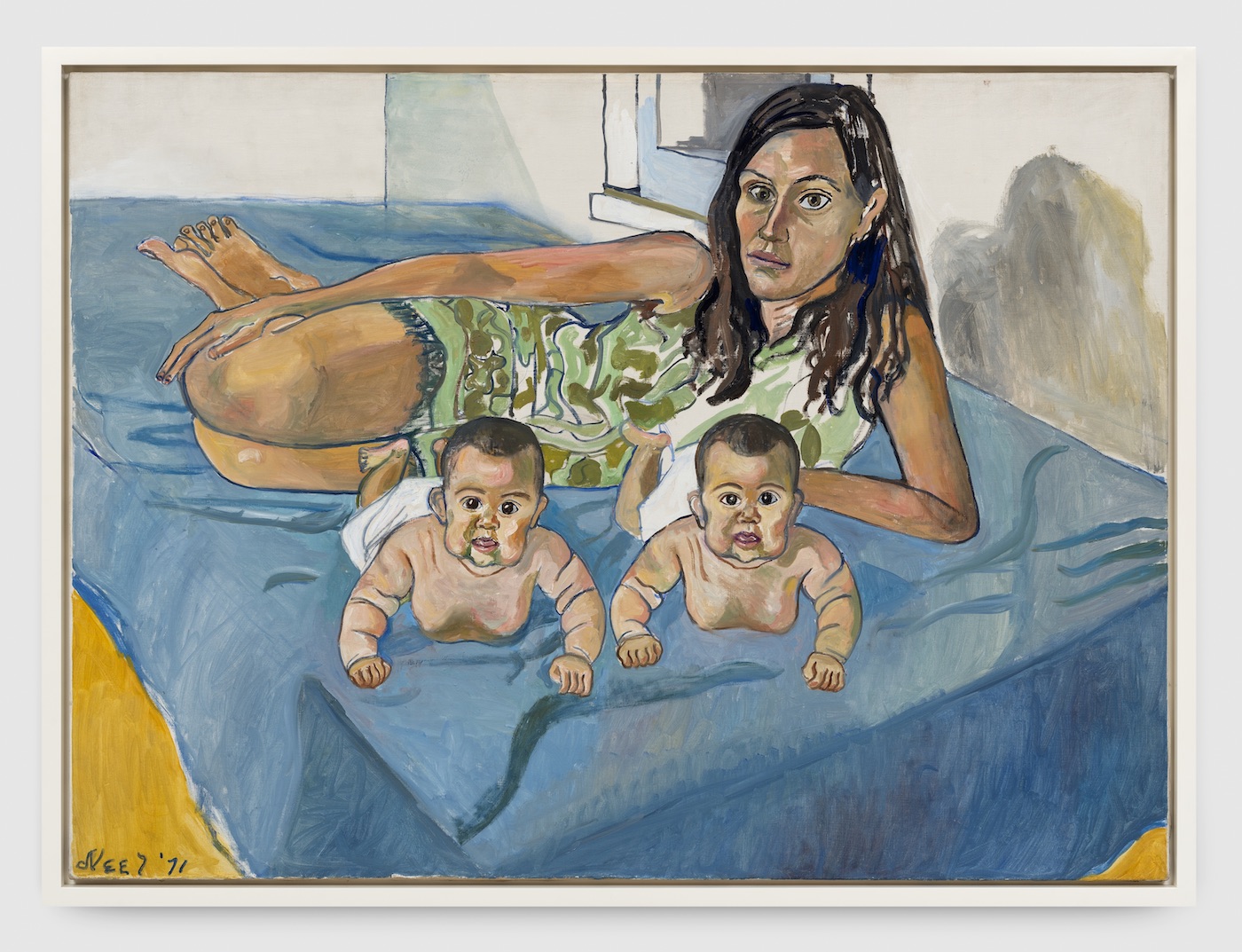

When you wake up at 4.30 in the morning, by 10 you tend to feel very strange indeed. Walking around town, pushing the pram, I feel like a floating face, blinking with dry eyes into a vanishing coffee cup. Looking at those other vague shapes of people moving around their days, I feel somehow planted in space. I think of Alice Neel’s paintings of mothers, not for the first time. A few of her less famous works are now showing at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels—including some family portraits and landscapes she made while in Spring Lake and Vermont—when the painter was taking time out from time, which really means the city. These more homely, rustic paintings are equally as masterful as any of Neel’s Spanish Harlem portraits, but they speak of different relationships to their own time. Ginny and Elizabeth is a double portrait Neel painted in 1976 of her daughter-in-law and granddaughter, and it speaks strongly to me now of a creeping feeling of the inevitability of time.

Even as Neel painted the portrait, she must have felt a sense of time passing—that they would all look back at this painting one day, the child grown, the artist gone. It is a fleeting feeling of sadness I feel when I take a photograph of my baby, knowing we’ll look back on it, and it will look dated, and we will be older. Then there is Ginny’s pose in Alice’s painting: her deadened gaze fixed on the floor, her slumped, exhausted body—all that physical work, raising a child. It is not a sunny picture, but it is an empathetic one. I’d much rather have the latter.

Spending so much time with someone who has so little grasp of time has made me realize how much parents know about time, and how to efficiently squeeze it. I also feel that, since having a child I am part of time—as if I’ve been shifted along in history, I’ve moved along the line. I am not an end, it isn’t only me with all that time to follow. It’s the loss of selfhood that women often talk of when they’ve had children. I’ve never thought more about my own death since becoming a mother—not in a hyperbolic, tortured goth, way, but more pragmatically. It’s as though as my daughter’s future stretches out ahead of her, mine is receding, to make space.

The thing about time is, no one knows when it began, or when it is going to stop. But as “I”, in Withnail and I says: “Even a stopped clock tells the right time twice a day.”