Buenos Aires, April 1977. A group of a dozen women gather in the Plaza de Mayo, in front of the presidential palace—a fearless display of defiance in the face of the government’s ban on mass assembly in public. Wearing white scarves wrapped around their heads, the women are united by the fact that they lost children during Argentina’s military regime that decade. Since the early 1970s, more than 30,000 children and young adults were abducted by the government across Argentina.

“The radical and motivating force of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo was love”

A year after the first mothers met at Plaza de Mayo to march—arm in arm; in silence; the embroidered names and birth dates of their children on the headscarves they wore—their numbers had grown to hundreds. They were becoming a political force to be reckoned with, demanding answers from the government and the patent human rights violations that had taken place. Three of the founders of the movement were kidnapped and killed, but they didn’t give up. Their marches continued until 2006, and over the decades the movement led to prosecutions against members of the Junta, the identification of missing children and the recovery of remains of some of those who were murdered.

The radical and motivating force of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo was love—they embraced their emotional strength and power, challenging their roles and social standing in patriarchal Argentinian society. They were revolutionary not only in the actions they galvanized but in the perception of motherhood. It’s this that inspired the artist Anna Maria Maiolino, who came into contact with the Madres in Argentina and created an installation project in response in 1991—although the work wasn’t seen until 2019.

“Love becomes revolutionary whenever we take a stance in favour of human rights and against acts of violence,” Maiolino explained in an interview earlier this year

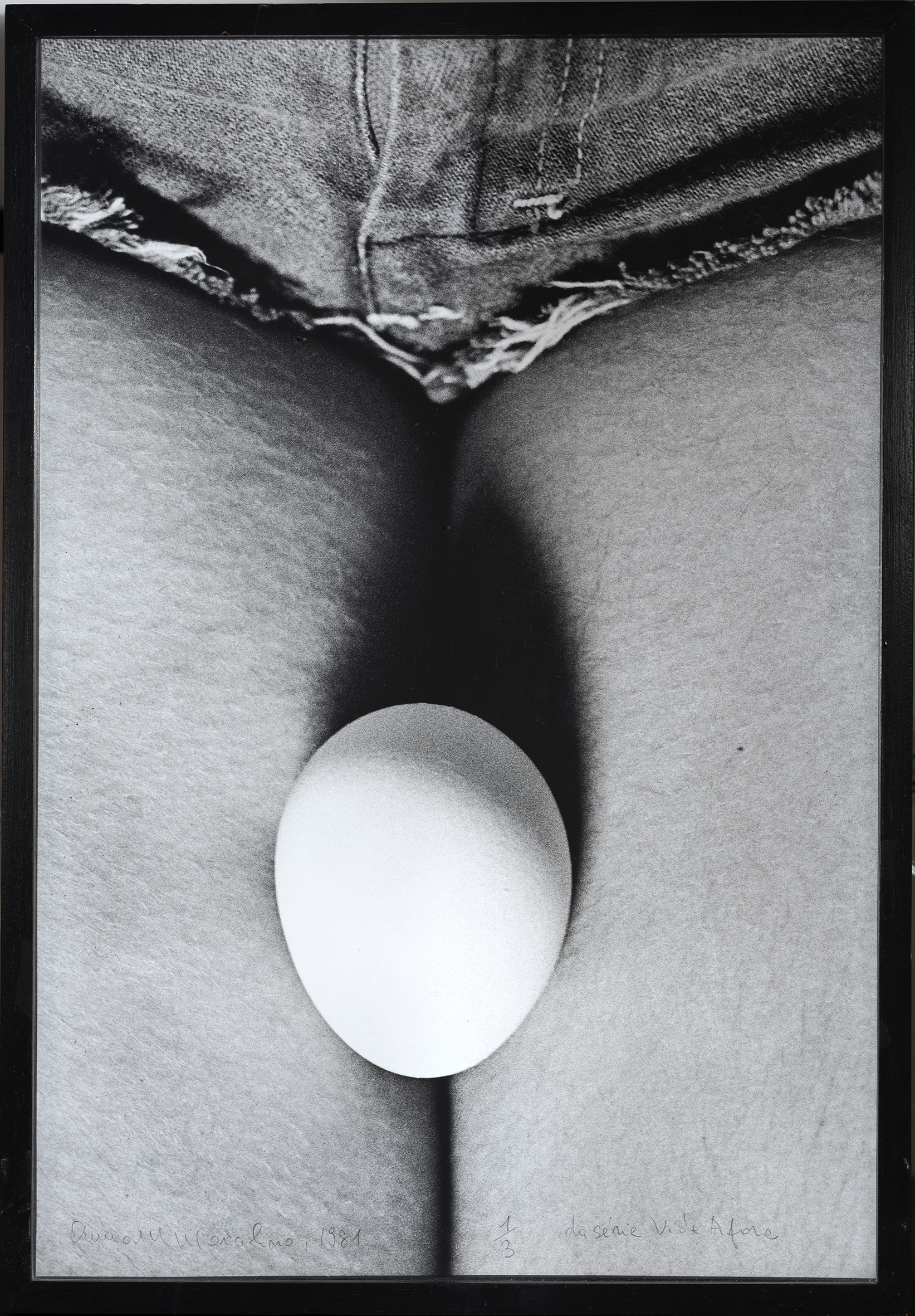

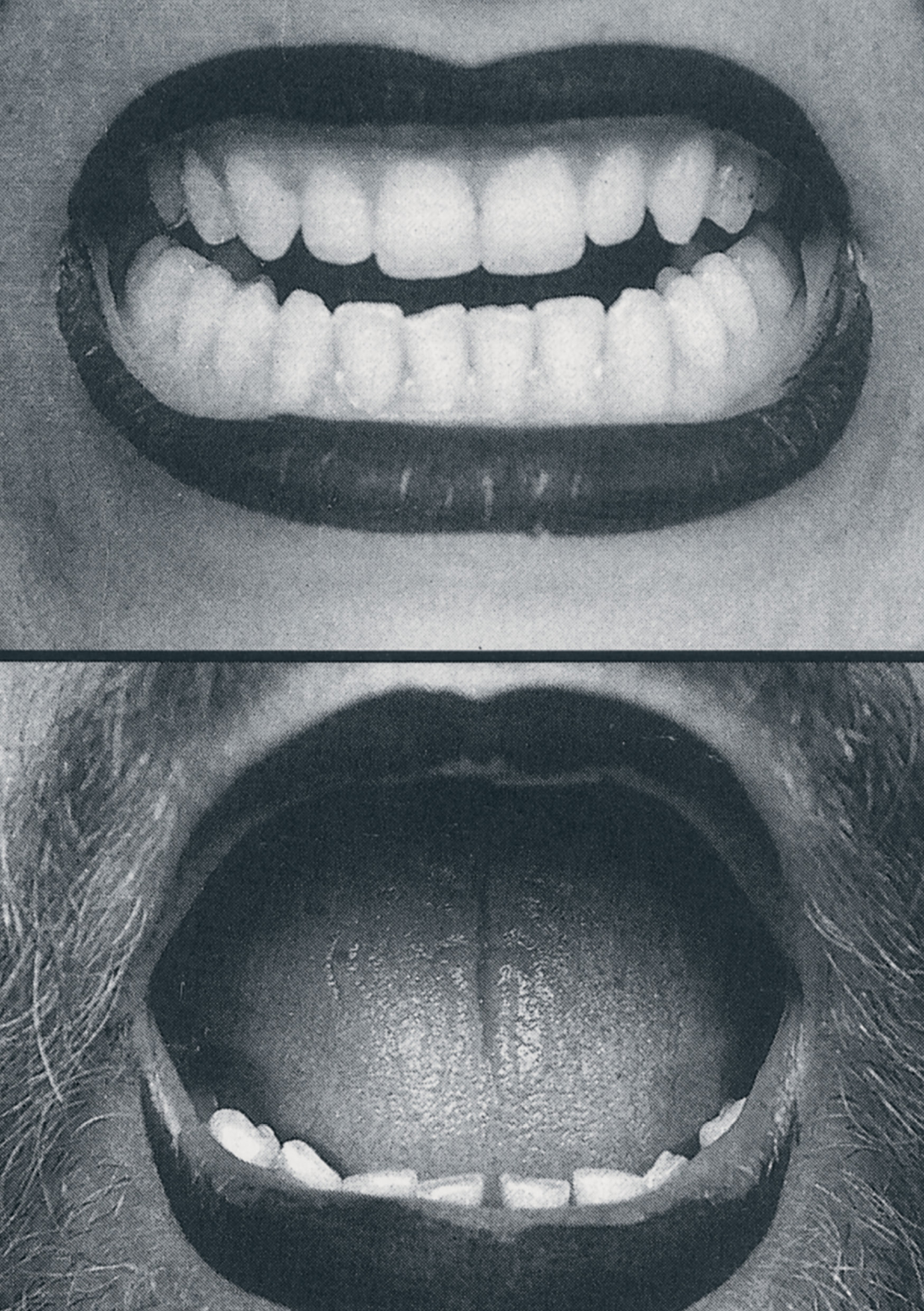

, when the work was finally presented at the artist’s largest-ever exhibition, at PAC Milan. Titled Making Love Revolutionary, the exhibition is now running at the Whitechapel Gallery, London (until January 2020)—Maiolino’s first major retrospective in the UK. The show contains more than 150 works made over a fifty-year period, from early prints to politically charged Super-8 video works and documents of performances in the 1970s and 1980s, to clay sculptures and floor-installations made in the 1990s, as well as sculptures completed in recent years. Her choice of medium shifts but every work contains the same raw energy and stark symbolism. Motifs of mouths, starving, fed, taped up, subjected to scissors; clay shaped into what resembles piles of excrement; the works speak of Maiolino’s own personal and political struggles, oppression, language and identity. Eggs reference female fertility and fragility at once; what is stereotyped or subdued in cultural imagery and iconography becomes intentional, forceful in Maiolino’s reclamations.

“The mother is always at the centre: revolutionary, as they are raising the next generation”

Maiolino left her native southern Italy in 1954, aged twelve. Her family (mother, father and nine brothers) emigrated to South America—first to Venezuela, then to Brazil, where the artist would remain for much of the next six decades, living briefly in New York. Her work connects wider movements and political events to her personal experiences of exile, deprivation and survival under patriarchal and dictatorial regimes. In this, the mother is always at the centre: revolutionary, as they are raising the next generation.

Motherhood has been a recurrent theme throughout Maiolino’s extensive oeuvre; one of her best-known works is perhaps Por um Fio (By a Thread), from the photo-poem action series the artist made between 1976 and 2000. In the analogue, black and white picture, three generations of women—Maiolino, her mother and her daughter—are joined by a string of spaghetti held in their mouths. The photo-poem establishes the artist’s matrilineage as a way, as in many of Maiolino’s works, to address dislocation and displacement. Her own identity as an artist and as a mother, she has said, was divided. Although she was sidelined and struggled to create alongside her role as a mother, Maiolino managed to make intellectual work that reflects the profound cultural and political possibilities of motherhood and femininity—like the Argentinian Madres of Plaza de Mayo.

As Maiolino put it herself, “discourses of resistance against ideologies and dominant social impositions through metaphors and metonyms” pervade her works. Like the Argentinian mothers, Maiolino has said her work is an attempt “to notice and resist repression in an attempt to make anti-conformist, politically interventionist—and therefore revolutionary—art that tries to retrieve what the human being has of essence, dignity, and that can also lay the responsibility on the ethical conscience in the face of the generalized violence and misery of today’s world.”

Anna Maria Maiolino: Making Love Revolutionary

Until 12 January 2020 at Whitechapel Gallery

VISIT WEBSITE