The bending of matter, objects and meaning becomes a recurrent theme for Jurriaan Benschop on a visit to Helsinki, where Mona Hatum and the International New Media Art Collective both balance material and immaterial content in vastly different ways.

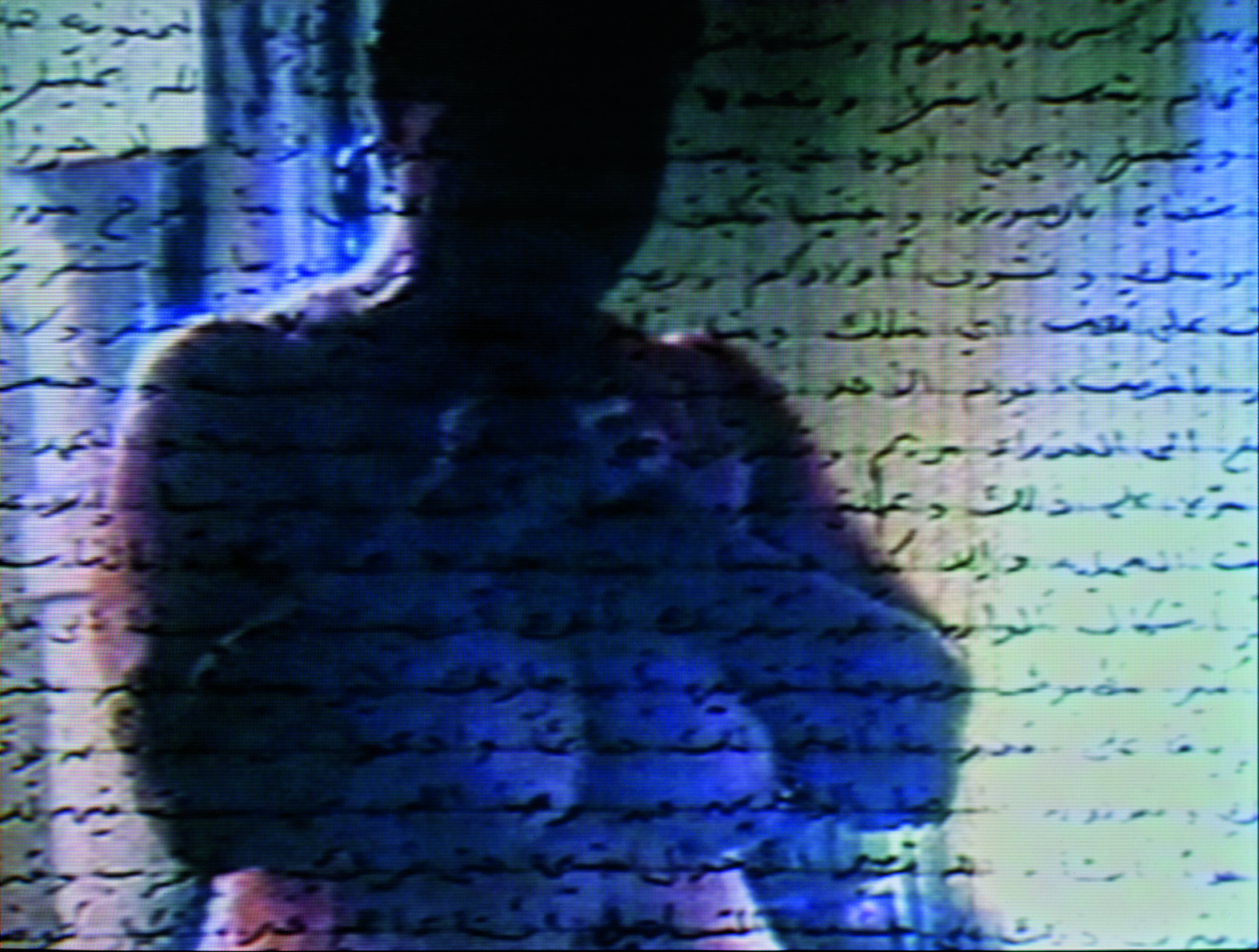

I visit Helsinki on a day trip from Tallinn, to see Mona Hatoum’s exhibition in the Kiasma museum and get a glimpse of the local gallery scene. The boat leaves early morning with few passengers, most of them are truckers using the two-hour trip to get some sleep. Outside on the deck I wait for the first daylight, the sky is changing from midnight to greyish blue. The actual start of the day is hard to catch. Somewhere in the waters around me are the territorial borders of Estonia and Finland. Crossing a border, leaving land to get ashore in a foreign country, seems a good way to prepare to see Hatoum’s work. She has an interest in maps, in questions of belonging, home and displacement. Hatoum’s biography, having grown up in Beirut as a child of Palestinian parents, finding exile in London as the war in Lebanon started, has informed her work which has gained mass attention in recent years. The eponymous show in Helsinki is the last station of an exhibition that previously was on view at the Centre Pompidou in Paris and at Tate London.

Home, 1999, offers a tense view of what could be a domestic situation. There is a table with all kinds of metal kitchen aids. They are connected through wires, and in some of them are bulbs that light up at intervals, accompanied by a penetrating buzz tone. The interior can only be seen through a fence of horizontal metal wires, it is not possible to enter the room. All in all, it is an uncanny environment, the opposite of a homey kitchen table where the family gathers. Light Sentence, 1992, in the neighbouring space, is a locker room where all the lockers are made of wire mesh, they are empty and transparent. In this case, the play of shadows on the wall caused by a moving light bulb completes the installation and transforms the bare, minimal aesthetic into an environment of suspense.

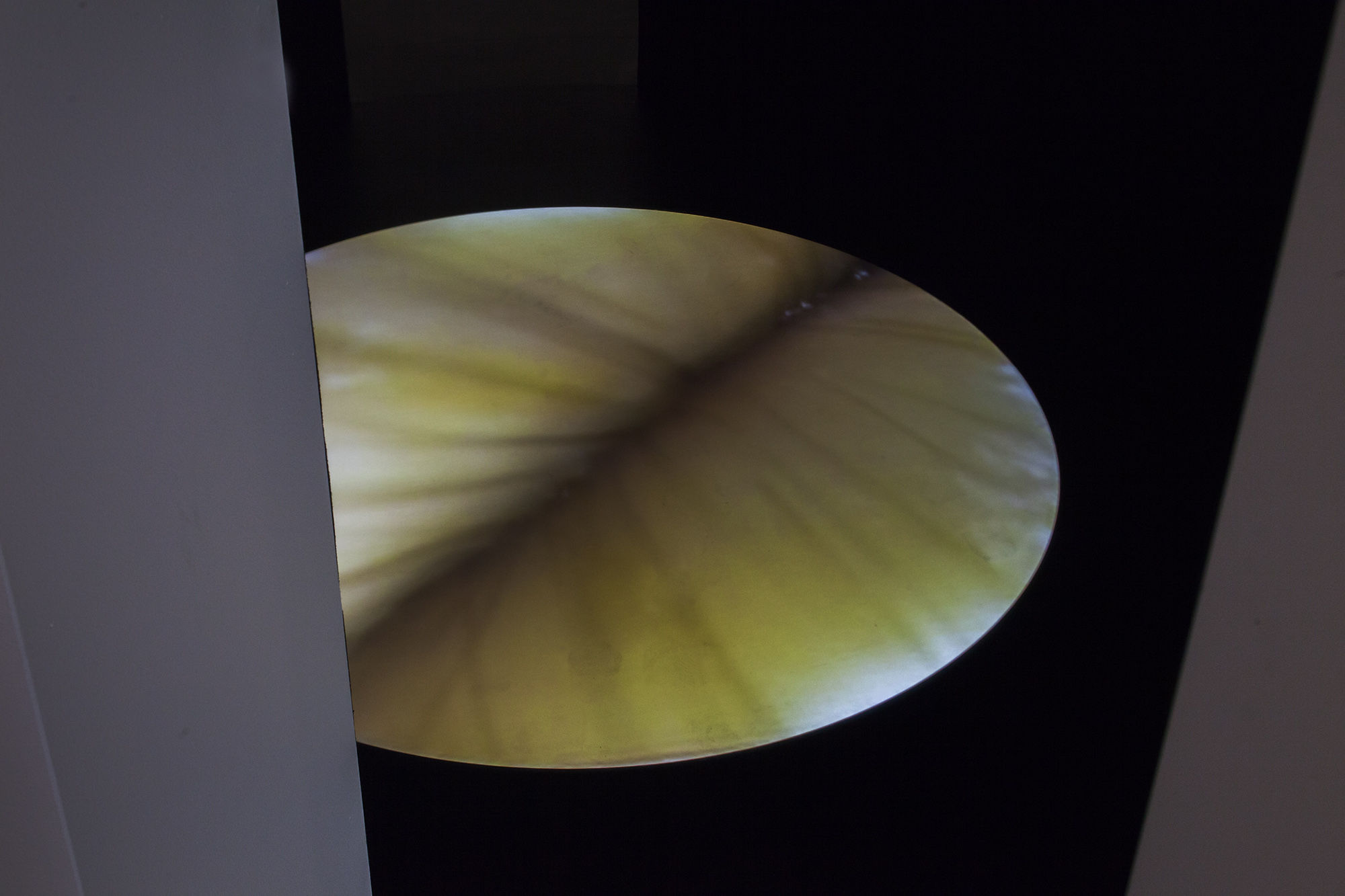

After walking through the show twice, having followed the parcours from Hatoum’s early, physical performances, to later sculptural works that symbolically address conflicts, I feel it is a sad exhibition. Is this what the artist was aiming for? I am not sure. There are certainly things I appreciate, like the decisiveness in Hatoum’s attitude and her courage to show things as she sees them, no matter if it confronts or pleases the visitor. An early work like Corps etranger, 1994, is very precise in its aesthetics. You step into a narrow, vertical cylinder and see a round film projection on the floor of a camera’s travel into the intestines of the artist, and also into her mouth and nose. This is an unpleasant work, but beautifully staged and executed. The presentation lifts the endoscopy into an inescapable piece of art.

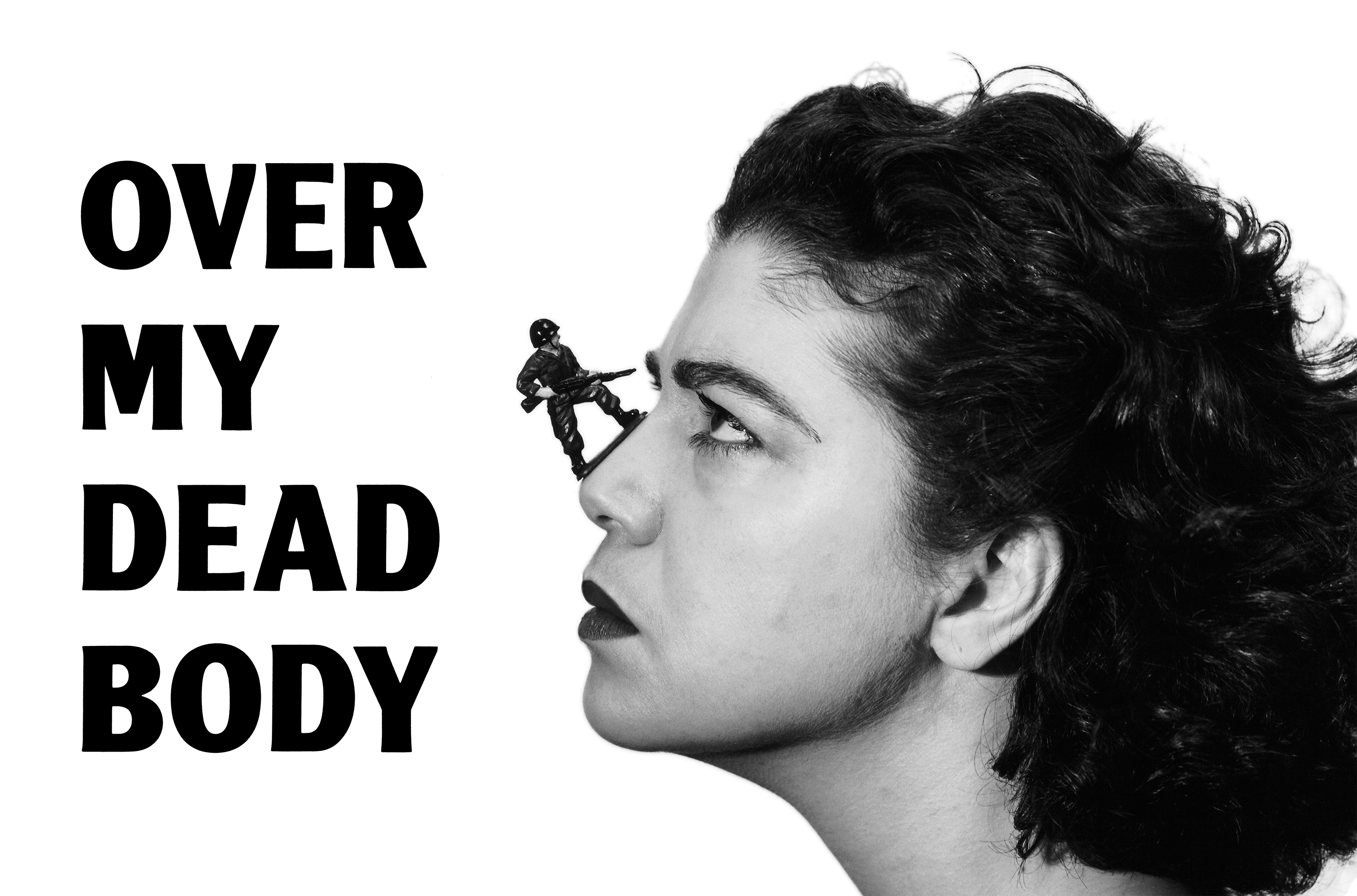

The exhibition makes me wonder what a trauma, conflict or unpleasant experience needs to be successfully transformed into an art piece. Clearly Hatoum digs into her biography, and her observations as an artist in exile have shaped her eye. She is among many artists nowadays who are aiming for political relevance. The danger is that this ambition takes over the work, and instead of an artwork you are looking at designed thoughts or, even worse, conceptual kitsch. For Present Tense, 1996, Hatoum bought many soap pieces in a market in Nablus and laid them out on the floor, forming a rectangle. On top of it, she made in red a map of territories that should have been handed over to the Palestinians, according to the 1993 Oslo Peace Treaty. The soap is supposed to work symbolically here. When a work becomes so literal, there is not much left to imagine.

Hot Spot, 2006, is a steel sculpture of a globe with the world map drawn in red neon. Hatoum chose the title to stress that the whole world has become a political hot spot. That is, once more, not a very enlightening thought. Hatoum’s exhibition is, as Adrian Searle wrote adequately in the Guardian, ‘electrified, if not always electrifying’. On the other hand, Hatoum presents works that do convince. In Natura morta, 2012, some precious coloured Murano glass sculptures appear as grenades, displayed in a medical cabinet. They are pretty little flowers of evil. In + and – , 1994-2004, a rotating steel blade simultaneously creates and erases lines in a round sandpit. In these cases, the beauty of contradiction explains itself, and the image as such is appealing.

In the afternoon I tour some galleries in Helsinki and I am lucky to run into the finissage of the exhibition Videokaffe at gallery Anhava. Here the International New Media Art Collective is at work in collaborative action. What binds them is an interest in kinetic art, as Thomas Westphal, one of the members, explains. He is a German-born artist who moved to Finland in voluntary exile you could say. The title piece can be found in the cellar, where a domino chain of self-built machines puts some balls in movement, which eventually creates pressure in an espresso machine. The artists have occupied the gallery space for the time of the show and transformed it into a laboratory and studio to develop pieces. Meanwhile, part of the gallery is reserved to show works that each of the members has made individually.

Looking at the works in this group show, once more the question comes up of how material and immaterial content is balanced in a work of art. The artists in Videokaffe stay close to the materials and their qualities while developing their sculptures. They find wonder in how functional mechanics can be altered, and through that the meaning of objects also bends. Hatoum’s bending of materials seems to spring more from preconceived images or thoughts. While Hatoum’s practice is solitary, and feeds on an individualised if not isolated perspective, this exhibition looks for sharing and creating knowledge through collective thinking and working.

A piece by Olli Suorlahti, Developing a Technology to Cut Down Energy Consumption, 2016, is a mechanical device that moves in a loop and tries to cut its own power cord. My favorite piece, Dragon, 2016, is made by Mark Andreas. It is a wooden sculpture, a bit like a propellor with three blades or ‘horns’. Inside there is a tube system that holds water. Through a slow process of vaporisation, movement is created, at least in theory. You don’t see it. This sculpture, clear in form, carefully executed and with a hidden dynamic potential, sticks in my mind, although I cannot stay long enough to wait and see it move. I have to catch the ferry.

Mona Hatoum, Hot Spot, 2013. Kuuma paikka. Stainless steel, neon tube. 92 1/8 x 87 13/16 x 87 13/16 in. (234 x 223 x 223 cm) © Mona Hatoum. Photo: Finnish National Gallery / Pirje Mykkänen

Olli Suorlahti, Developing a Technology to Cut Down Energy Consumption, 2016