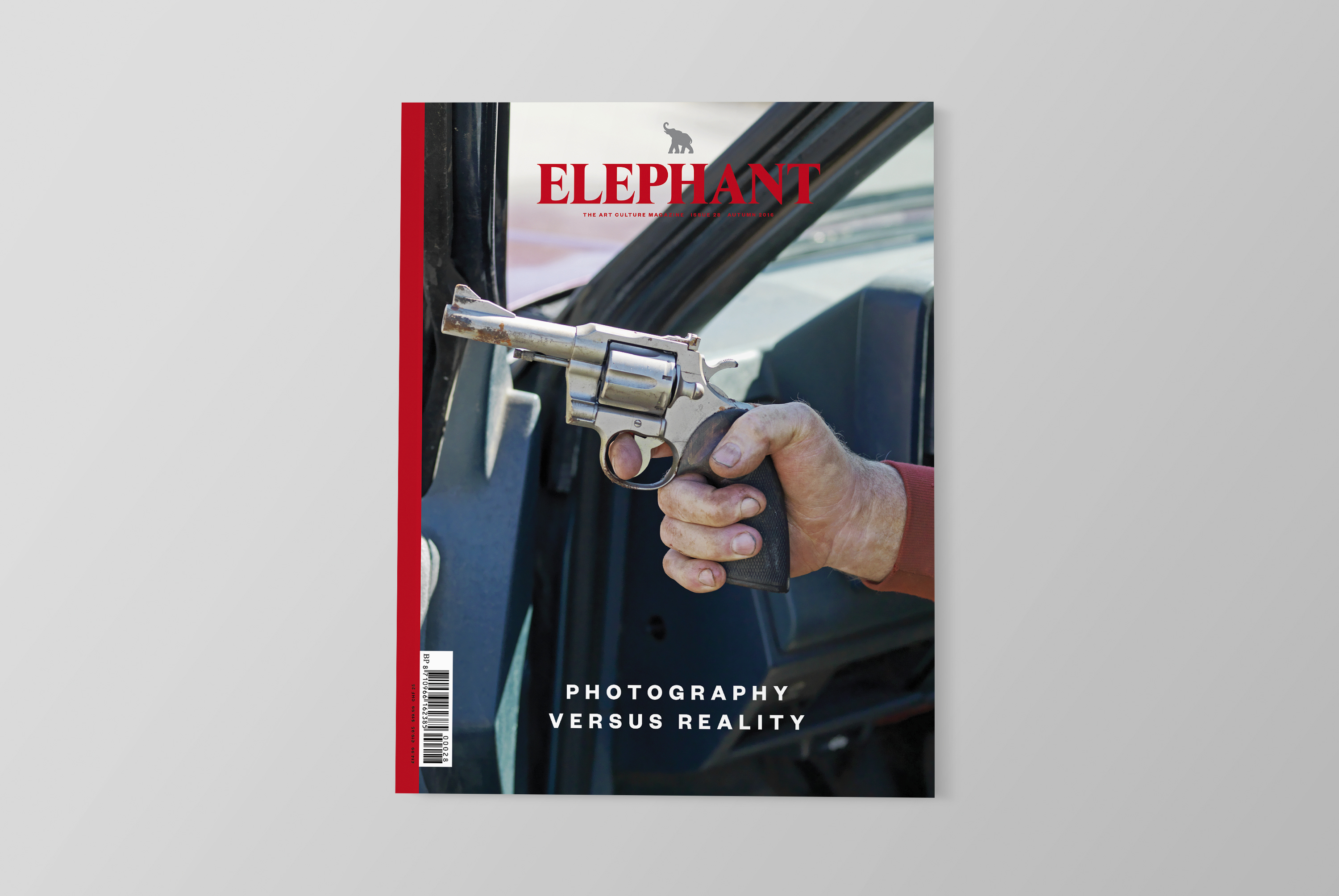

This feature was originally published in Issue 28.

‘I’m much nicer than people think,’ says Mr Bingo, famous for sending abusive postcards to those willing to pay for the privilege of being trolled by an artist.

We meet in the busy, buzzy offices of a digital product studio in Shoreditch, a hipster scene irresistibly suggestive of the satirical sitcom Nathan Barley. This is highly appropriate since Mr Bingo, who is only borrowing a desk here and is the only artist in the building amid teams of brand and app designers, is himself a satirist. Above his desk sits a likeness of his head made by Wilfrid Wood, formerly of Spitting Image, and although he acknowledges a debt of influence to artists David Shrigley and Paul Davis, he says he is in fact ‘much more influenced by comedy than by illustration. Things like Monty Python, and more satirical stuff like Chris Morris’s Brass Eye and Blue Jam.’ (Morris, of course, was one of the creators of Nathan Barley.)

‘I don’t think I’m a very good illustrator,’ he goes on. ‘I think I’m a good marketing person in a way, and good at selling myself as a product, as a brand, as a thing.’ The self-branding began early, when he earned the moniker ‘Bingo’ in his teens (after winning £141 playing—you guessed it—bingo) and decided to adopt it. He added the ‘Mr’ at age 21. ‘Now it’s slightly embarrassing,’ he comments, ‘a bit like Arctic Monkeys, a name you come up with when you’re a teenager and then it becomes successful so you have to stick with it.’

Mr Bingo also found his vocation early. As a child growing up in Kent he loved drawing ‘funny stuff that got a reaction’. After taking an art foundation course in Maidstone, he studied graphic design and illustration in Bath. He then moved to London and worked episodically in a shoe shop, a PR company, a bank and a bookshop. So how did he manage the transition to freelance illustrator? ‘Every spare minute I had while working in these dead-end jobs I was trying to make illustrations, bits and pieces like night-club flyers, and then eventually I started getting enough stuff and making a name for myself so that I could go full time. A lot of people would have given up in the three years when I was trying and didn’t have immediate success. Many students think they’ll come out of university and be an illustrator, but there isn’t a junior position in illustration. You have to be tough.’

Success came with commissions from GQ, the Guardian and the Financial Times, and advertising work for clients such as Nike, VW and Virgin. How did he deal with the big corporate world? ‘My manifesto was always to make the client think they were getting what they wanted,’ he replies, ‘but actually draw exactly what I wanted, and for the piece to work as a standalone image for people to enjoy.’

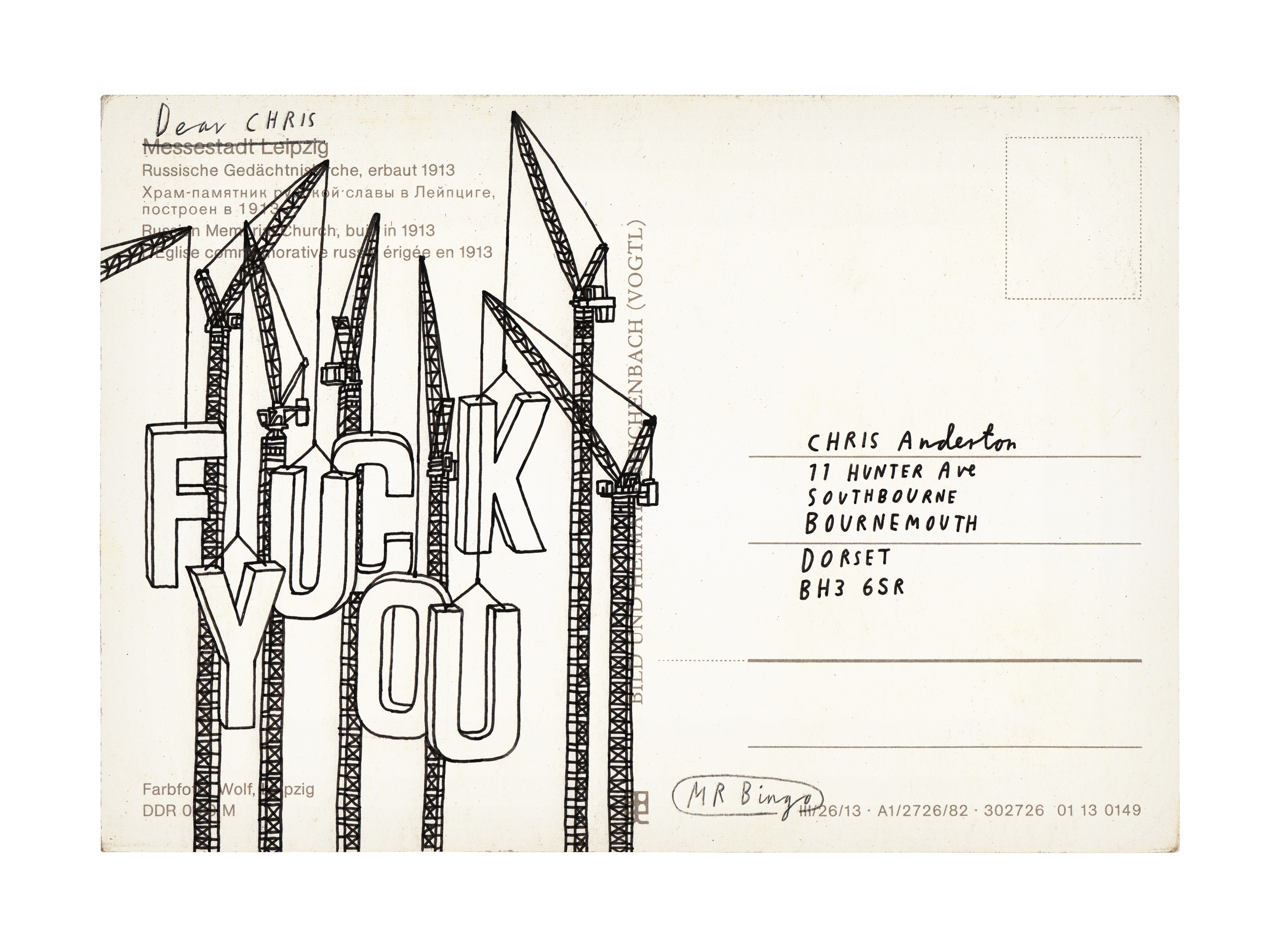

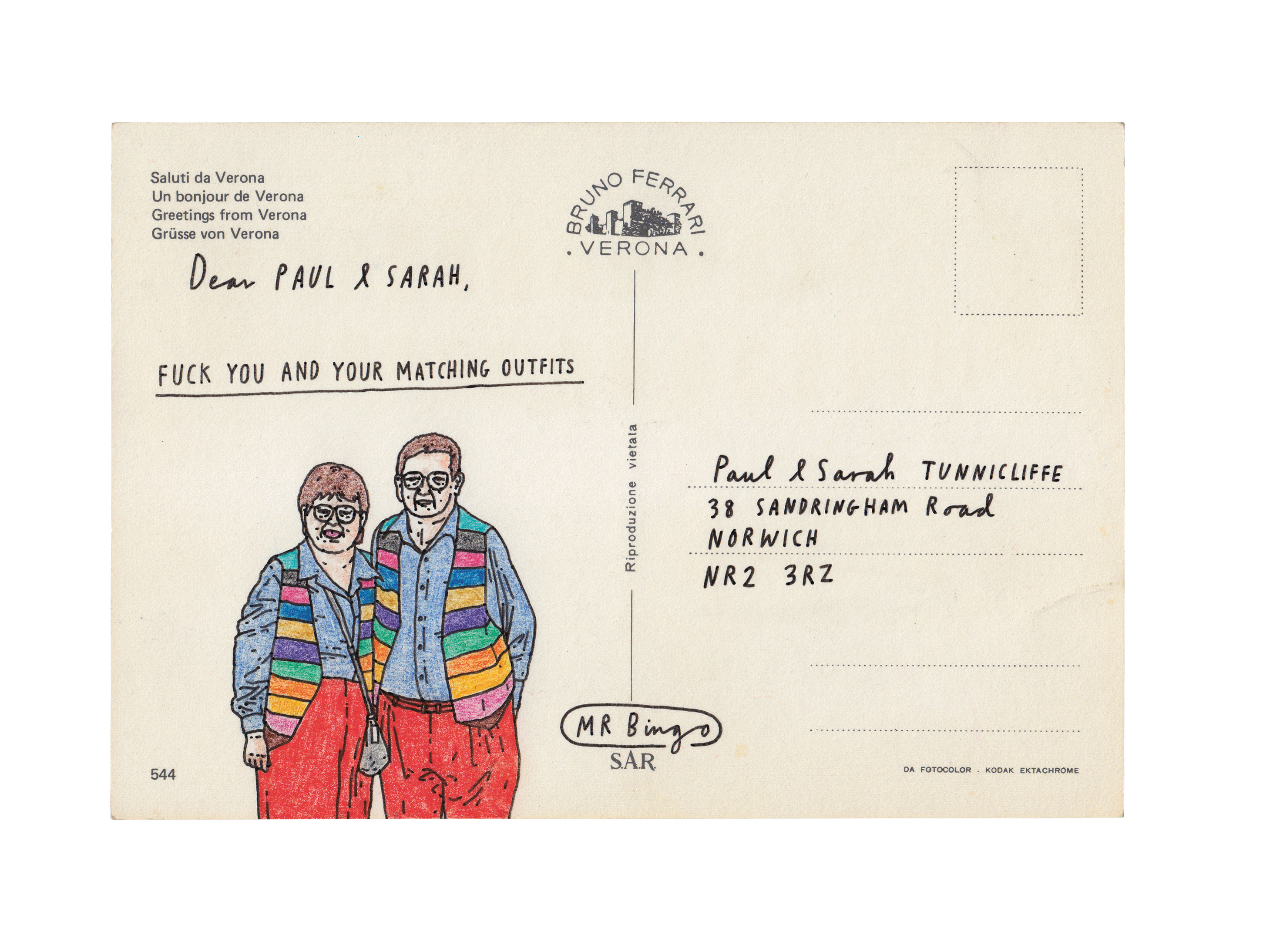

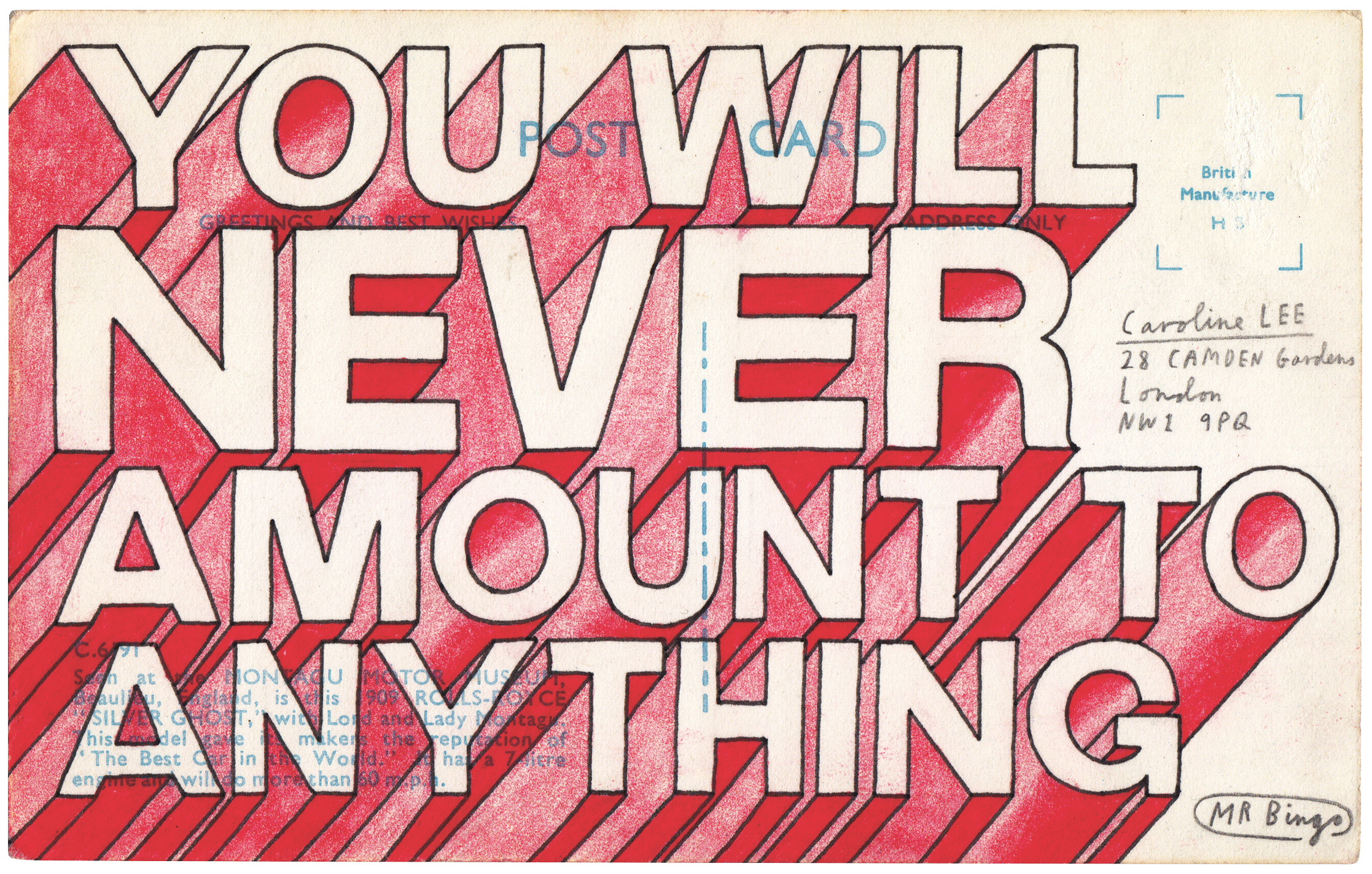

He gave up commercial illustration about a year ago, making official an evolution from illustrator to artist that had begun with Hate Mail. This project happened ‘by mistake’, coming to him one night as he sat in his studio looking through a lot of postcards. ‘I’d been drinking and I suddenly wanted to send a postcard to someone telling them to fuck off. I though it’d be funny, so I went on Twitter and said I’d send an offensive postcard to the first person to reply to this tweet, and lots of people replied really quickly. It got talked about online and I started getting messages from people saying “Please, please, please can you send me one?” You can tell when something gets popular and hot. A few days later I opened a service charging people five pounds for an offensive postcard and made sure it got onto a few blogs, and I had to close it after three days because I got too many orders.’

The scarcity of the postcards only enhanced their cult status. Over the next five years, the artist would open the service for a few minutes at a time and the price gradually went up to £50: ‘It is quite expensive for someone telling you to fuck off,’ he says, ‘but for a signed piece of original art, it’s really cheap.’ He signed a deal with Penguin to turn the project into a book which had to comply with traditional marketing guidelines: ‘A big title that made it obvious what was going on, a celebrity quote on the front: I didn’t want any of that. I felt I had lost control.’

A few years later the situation was triumphantly rectified when Mr Bingo decided to do a second book, a ‘best of’ Hate Mail (out of a total of 1,008 sent postcards), funding it through Kickstarter. ‘I was aiming to raise £35,000 and secretly hoped that it might get funded over the 28 days [of the appeal],’ he recounts. ‘And then it funded in nine hours and I got £135,000.’ The lure for backers must have lain not only in the subversive humour of the project and the catchy rap video that accompanied it, but also in the highly original rewards on offer—the artist coming around to do your washing-up, or getting drunk on a train with you for four hours.

Cloth-bound and with gold-foil stamp, the resulting tome, Hate Mail: The Definitive Collection, is a beautiful high-end object, which is another joke. ‘No publisher would have published it in this form: the unit cost was far too expensive. And I purposely didn’t put my name or the title on the cover: another “up yours” to the publishing world.’ (The front cover actually bears an image of an octopus flicking eight ‘up yours’ V signs at all-comers.)

Bingo’s astute use of social media, his outgoing directness and approachability—unusual qualities in the art world—have earned him a considerable following on Twitter and Instagram. ‘If someone buys a book from me it’s my handwriting on the package and maybe a little message or something,’ he says, ‘rather than just being a faceless company. But it’s a lot of work, obviously. And the more you grow, the more you have to do to keep everyone happy.’

There are personal rewards for the dedicated artist: strangers send him gifts, most remarkably perhaps a beautifully crocheted ‘bag of dicks’, in tribute to one of his drawings. ‘I love getting things in the post,’ he says. ‘But I also find there is this weird pressure from having built up such a following. You’ve got this hungry audience of fans going “What’s your next big thing?” Every day, someone says it. But why does it have to be a big thing? Why can’t the next thing be a tiny thing, or nothing? That pressure keeps me awake at night, pressure from strangers who think they’re just being kind. It’s also quite crippling.’

Yes, all right—but what is his Next Big Thing? We meet on the day the result of the Brexit referendum is announced—that certainly heralds a new era. Mr Bingo was saddened by the news and is wearing a black T-shirt that reads ‘No Fun’. Might he now explore a more political direction in his work? ‘I wish I had more of an interest in the news,’ he says, ‘because I think I’d be one of the greatest political cartoonists. But I just focus all my time and energy on making funny pictures.’

I ask about his recent trip along the British coastline, the result of another one of his creative impulse decisions: ‘I thought it would be funny to hire a motor home. Instead of contemplating it for a few weeks and then never doing it, which is what most people do, I just booked it, and then regretted it immediately. So I went away for 16 days on my own, travelling around the coast of Devon and Cornwall and up into Wales. The whole of Cornwall was quite “Vote Leave” actually, posters everywhere.’ The trip, a sort of distillation of the classic British holiday, was documented on his Instagram and Twitter feeds. He seems to have cut a distinctive figure among the motor-home community: ‘I was probably the only person there under 50. And some of them thought it was weird that I was on my own.’ Was this part of a new project, perhaps another example of Mr Bingo finding himself in a performance art stance simply through what he calls his ‘attention seeking’? (He once returned from Germany with a big portrait of himself he had been presented with: ‘I really enjoyed getting back on the Tube and standing with it, and I made sure it faced out. A few people couldn’t help saying “That’s you” and I said “Yeah, I know.”’)

Of his motor-home adventure he simply says: ‘The plan was to go away and hopefully be inspired. I have this weird freelance guilt, this idea that I can never stop working. What actually happened was I just went walking, and while I didn’t come up with any ideas, I think it probably did reset my brain. I’m in a weird position where I’m making a living out of selling my book because it’s self-published, but I feel I need to do something else in order to be an artist.

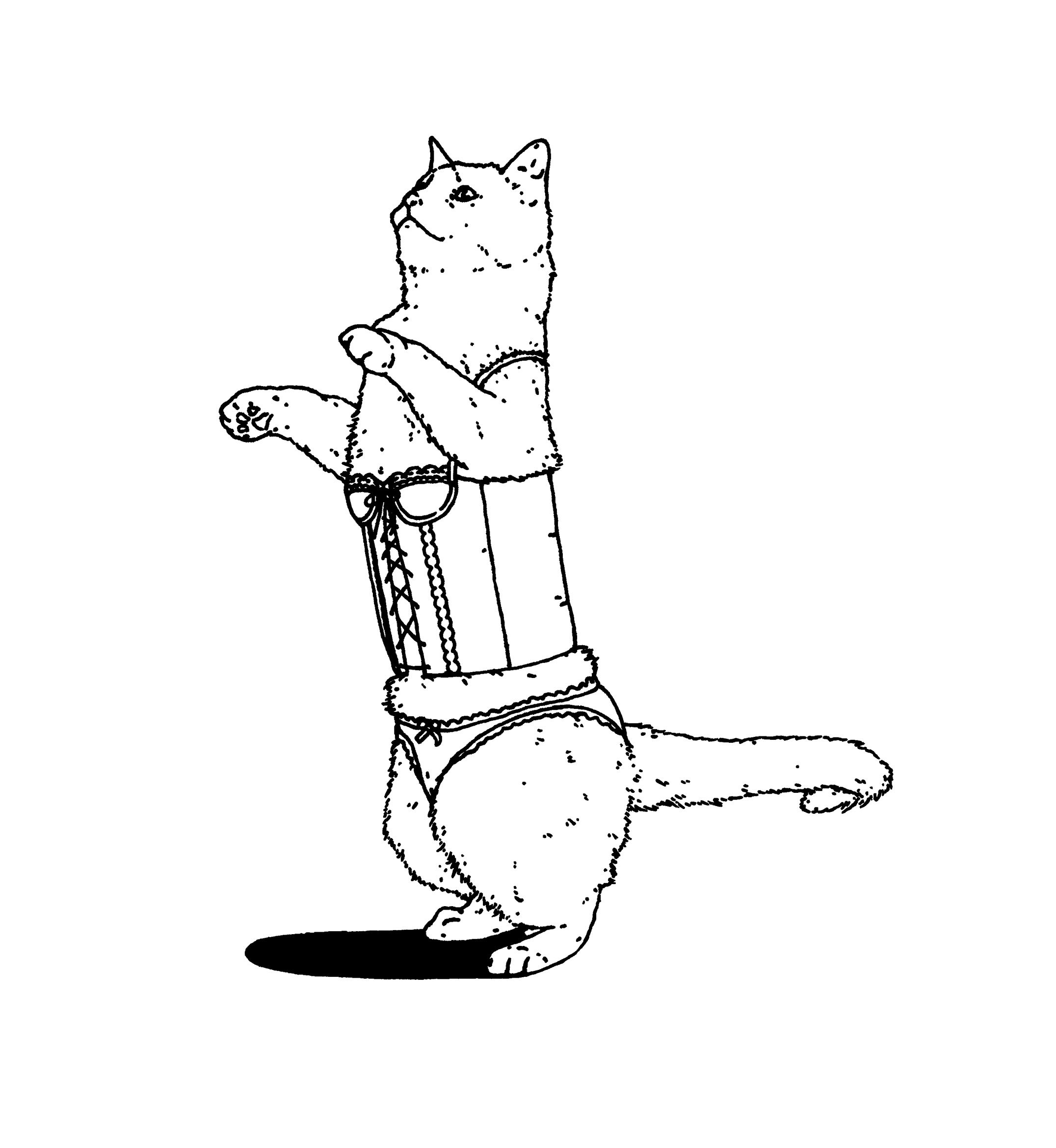

‘I’m just starting to experiment and play again. The plan is to keep evolving and making stuff, things that people are going to consume and enjoy. I’m very aware that things have a shelf life—apart maybe from black-and-white line drawings. I think they’re very timeless.’