Amidst the din of the traders and sharp elbows of the eagle-eyed punters at a marketplace, the character of a city truly reveals itself. Here, a cross-section of society comes together in the age-old ritual of commerce. Of course, a market offers more than just a quick bargain: it is a place for community, for rivalry and even romance. Families bicker, teens glare and elderly men and women put on their best coat for the morning. All these frictions and more are captured by Tom Wood in Women’s Market, bringing together photographs taken at the Great Homer Street Market in Liverpool between 1979 and 1999.

Wood lived in the city throughout this twenty-year period, slowly becoming a regular at the market with his camera. His presence is rarely noted by the subjects he snaps as they browse and haggle over children’s clothes and cosmetics, lending the images a distinctive intimacy—as if we too might be just a few feet away from them, leaning over to snatch another item from the pile in the foreground.

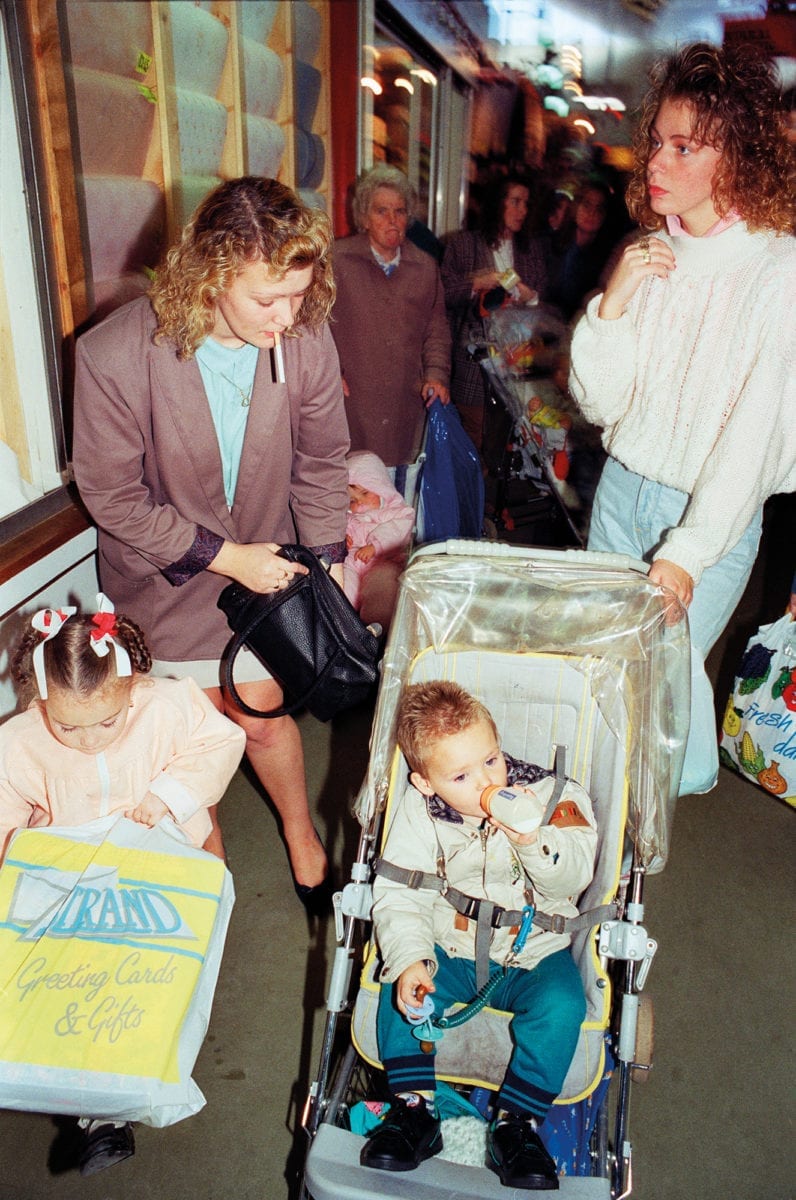

Shopping at Great Homer Street Market is serious business. The book opens with an image of two women pushing prams, one loaded with shopping bags on the handles with a toddler sat wailing in the seat, while her companion’s cargo consists just of heaped bags—the day’s purchases briefly becoming a sort of surrogate child. Bras and pants are displayed proudly to be picked up, stretched and inspected by the crowd, whose hands are seen entering or disappearing from shot throughout. Women in big earrings and patterned headscarves hold up clothes appraisingly against themselves, or subtly assess the choices of others—cigarettes often hanging out of mouths or from the end of fingers.

The market is a place for new costumes and fantasy as much as for everyday items; frothy tutus hang in one photograph, while in another a baby is seen dressed head-to-toe in a miniature sailor’s outfit. Frilled white children’s dresses hang next to a table labelled “PILLOW CASES 50P EACH” in an image midway through the book. The markers of commerce are everywhere, from printed plastic bags to bargain basement signs—a format that is mirrored in the book design itself. Distinctive white-daubed lettering runs across the cover on a bright pink background, in an imitation of the shouty price tag you might see announcing a two-for-one offer. Meanwhile, the title page wryly notes “Sold As Seen”, with text printed as if on a receipt.

“A market offers more than just a quick bargain: it is a place for community, for rivalry and even for romance”

Saturated colour and grainy black–and–white images are mixed throughout, and the sudden emergence of a shade of banana yellow or pink pastel shocks when it does appear. A photograph of a shiny red car, packed full to the brim with a family and their shopping, feels bright enough to burst off the page. Sunny mornings at the market bring out these deep colours all the more, and they are everywhere: on tracksuits, children’s outfits, helium balloons, crumpled tarpaulin, stretched awnings and bulging bags.

Faces push constantly into shot, bustling past one another, with Wood fully immersed in it all. The occasional acknowledgement of the camera’s presence by one amidst the many shoppers comes as a surprise, as if we (as onlookers) have been momentarily spotted in the crowd. Some children play up to the lens, a middle finger cheekily cocked, while a moody teen in a leather jacket strikes a pose with arms folded. Packs of girls roam with fully primped and puffed hair, offering up knowing, world-weary looks well beyond their years to the camera.

In another photograph, four teenage boys try on bright green and purple tracksuits together, serious for a moment in their sartorial splendour. Kids play and fight beside cardboard boxes, and there is a profusion of young couples across multiple shots, arm-in-arm or nestled tenderly on a bench together while the busy street around them goes about its business.

The latter half of the book ventures indoors, where interactions take on a newly formal look with the addition of hat stands, mirrors, cash desks, changing rooms and even security guards. At a tiled café, fry-ups and polystyrene cups of tea can be seen clutched in hands, a frilly lampshade dangling above, where punters have retreated for a well-earned rest. Here the book’s chronology begins to reveal itself, as images appear of kids crouched, tired and grumpy, on floors.

In its final photographs, the market stalls are stripped away, leaving behind only rubbish and detritus in the streets. Money has been spent, deals struck and snacks consumed. All that remains now are scattered wrappers, old Coca-Cola cans, piled cardboard and empty packaging, with a few dogs sniffing the ground and last stragglers picking their way through it all. We have experienced the market’s ebb and flow alongside them, a wordless narrative whose openness is a reflection of Wood’s abilities not just as a documentarian but as a storyteller. Women’s Market suggests lives far beyond just those of the people photographed within it, inviting us in to invent our own place amidst it all—and, if we’re lucky, pick up a few bargains along the way.