A talisman is an object imbued with magic. In Japan, Shinto shrines make red silk charms embroidered with gold thread to bring good luck; in India, a protective charm made by the Naga tribe might contain a potent cocktail of soil from the grave of a man killed by a tiger, a nettle leaf and the hair of a witch. In the Americas and Oceania, tree bark was thought to be able to seduce a woman. In Thailand, a “palad khik” is a surrogate penis, a symbol of male fertility, and can be seen hanging on the walls of shops and restaurants. In Nigeria, the Igbo people might carry an ikenga, a personal god, a mascot to protect from evil. Four-leaf clovers and horseshoes are also talismans. The history of talismans and their symbolism is long and varied, but what they share, in all cultures, is that they depend on faith. Anything can be a talisman, but you need to believe.

Yinka Shonibare is a psychopomp—or “a contemporary shaman”, as Antwaun Sargent put it—who has conjured the forces of more than forty contemporary talismans at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London, in a group show that restores our belief in art’s transformative, healing potential, whether material, social, political, economic or spiritual. Art has a talismanic quality, the ability to bring the past, the invisible and the unknown vividly into the present. It is something that we can meditate upon. An artist can turn an ordinary thing into an extraordinary thing. “The transformation of an everyday material—as evidenced in Leonardo Drew’s reconfiguration of materials into wall-based reliefs within the show—reflects its power to act as a totem or mascot,” Shonibare tells me.

- Zanele Muholi, Yaya Mavundla, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2014. © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Shonibare has chosen an impressive line-up of names for Talisman in the Age of Difference; artists whose work also closely connects with his own practice and ideas. Most were born in the African diaspora in the UK and US, some in Africa, and others simply, “empathize with the spirit of African resistance and representation.” Though working in different times and contexts—colonized, liberated, repressed, emancipated, African, American, British—Shonibare’s selection traces the heritage of talismans as an art form in Africa, and moves from these traditions to how talismans might manifest in contemporary ideas.

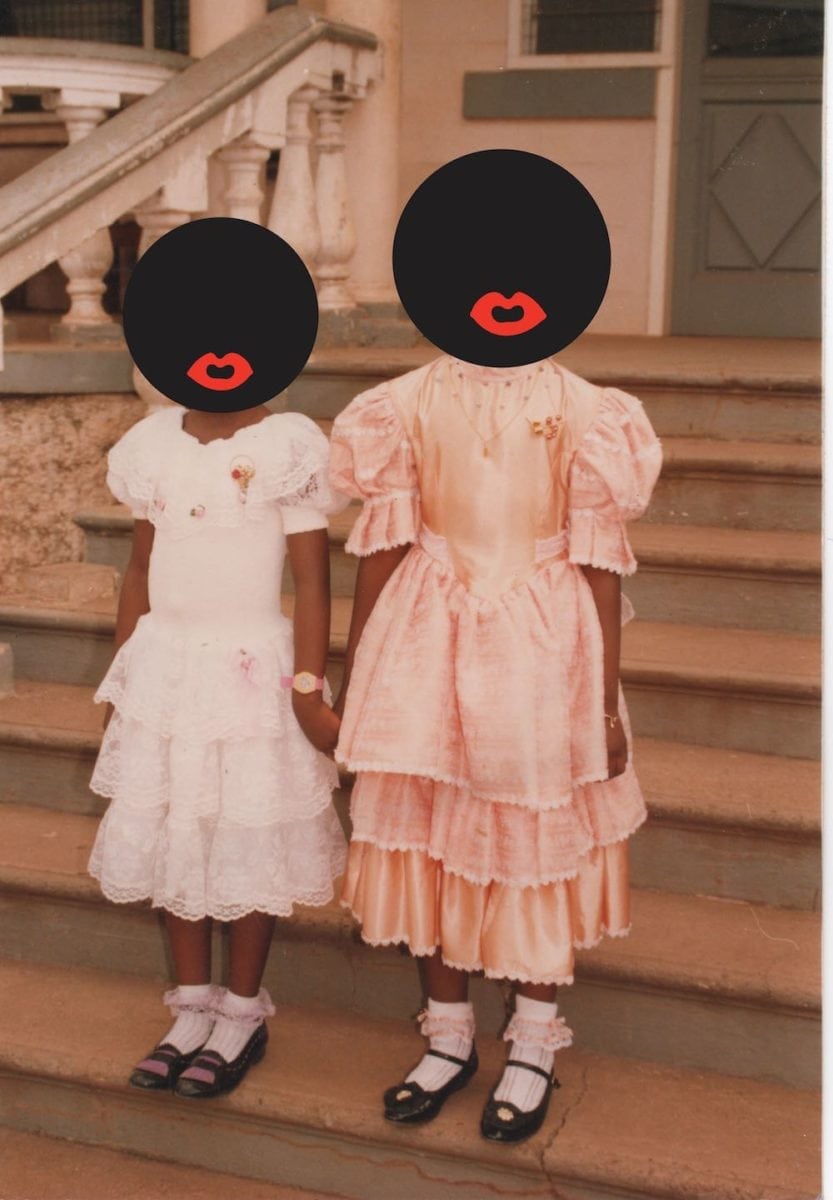

“We’re currently experiencing a resurgence of right-wing politics and xenophobia across the globe—we cannot shy away from the historical context of our identities,” Shonibare explains. “In the context of Me Too and Black Lives Matter it is important to assert difference and celebrate diversity,” he adds. “The work of David Hammons, John Outterbridge and Betye Saar is characterized by the transformation of cultural objects into magical, fetishistic assemblages, whilst the work of Genevieve Gaignard and Deborah Roberts shakes the foundations of tired, long-held beliefs about black identity.”

“Art has a talismanic quality, the ability to bring the past, the invisible and the unknown vividly into the present”

The expansive exhibition makes many synaptic connections—in Gallery One, an entire wall is devoted to six works from Whitfield Lovell

’s Kin

series, his signature Conté crayon portraits assembled with symbolic objects: a wooden clock, a hypodermic needle, a book and plastic wedding figurines, a way to suggest a narrative for his unknown subjects from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the same gallery, a self-portrait from Samuel Fosso’s groundbreaking 2008 African Spirits—in which the artist dresses up as Patrice Lumumba, the Pan-Africanist and first Prime Minister of independent DRC, executed aged thirty-five in 1961—summon the dead back to life in wistful homage, while continuing a tradition of costume and performance that refers to his own Igbo heritage. Famous or anonymous art immortalizes the presence of the forgotten.

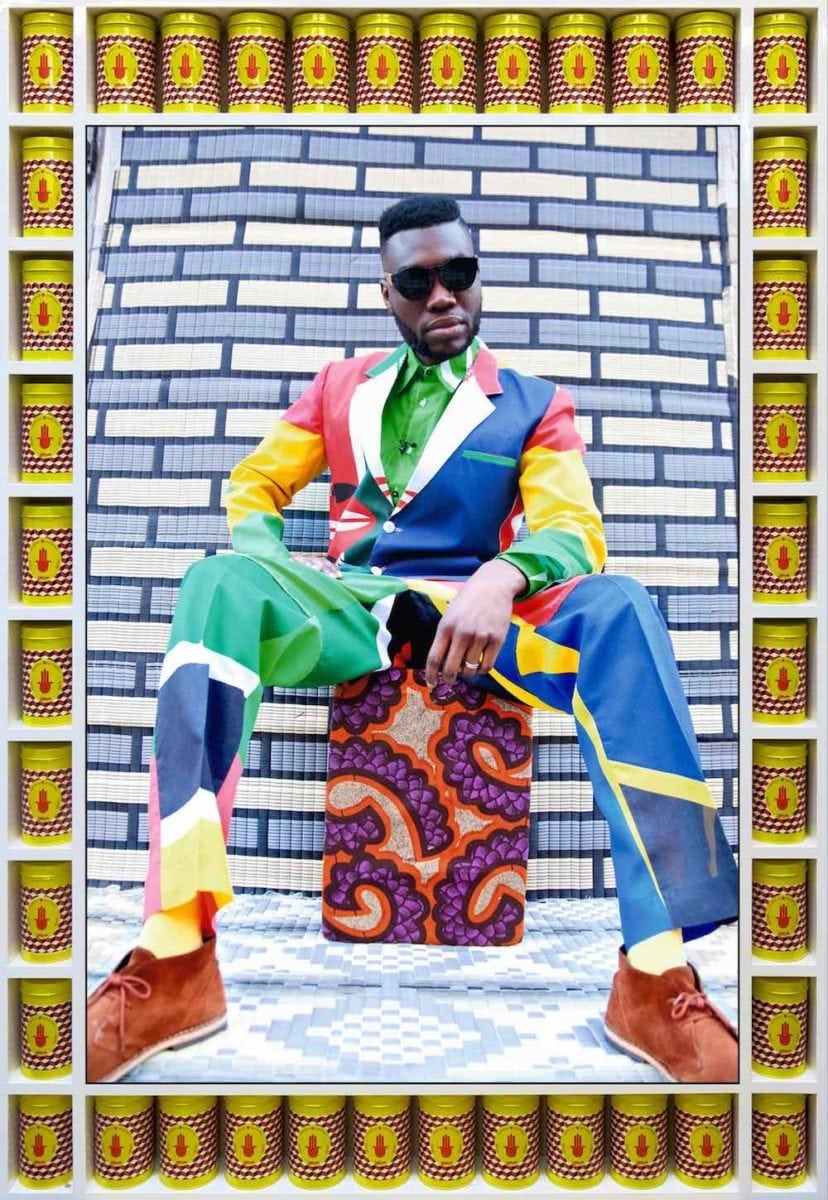

Art isn’t only a way to bring back the dead, but to elevate the living. Two new hyperrealistic portraits by Ghanaian painter Jeremiah Quarshie

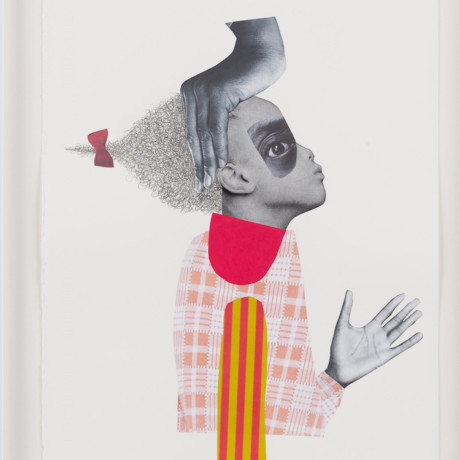

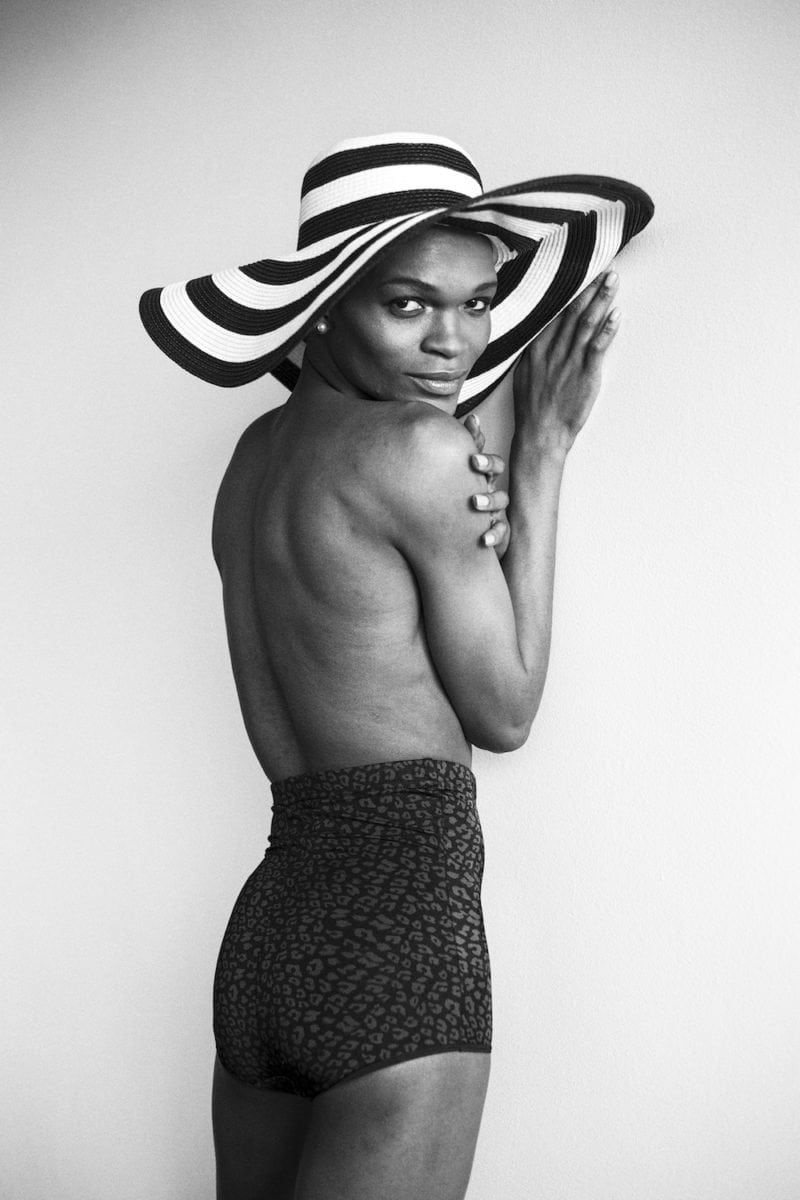

, Manyer (Queen Mother) and Queens No. 2 cast ordinary women as royalty; meanwhile, Morrocco-born, east-London-dwelling Hassan Hajjaj’s Bellydancer, a portrait of a male belly dancer shot in a make-shift photobooth in Marrakesh’s infamous square of tradesmen and tourists, elevates his subject and takes him as his talisman. “This exhibition is about artists proudly celebrating the transformative powers of art,” asserts Shonibare, which is certainly true of Zanele Muholi’s visual activism, that has empowered figures in her community who were invisible in the national media by celebrating them in photographs that have travelled all over the world. Five photographs of trans women by the South African artist feature on their own wall, including two portraits of Yaya Mavundla in Parktown, Johannesburg, who now organizes the Mzansi Pride festival in South Africa, and is a promoter of LGBTQI rights in the country. For Muholi, these people—her people—are talismanic leaders.

- Larry Achiampong, Glyth (series 2), 2018. © Larry Achiampong, courtesy the artist & Copperfield, London

- Genevieve Gaignard, The Golden Hour, 2017. © Genevieve Gaignard, courtesy of the artist and Shulamit Nazarian, Los Angeles

“Shonibare’s selection traces the heritage of talismans as an art form in Africa, and moves from these traditions to how talismans might manifest in contemporary ideas”

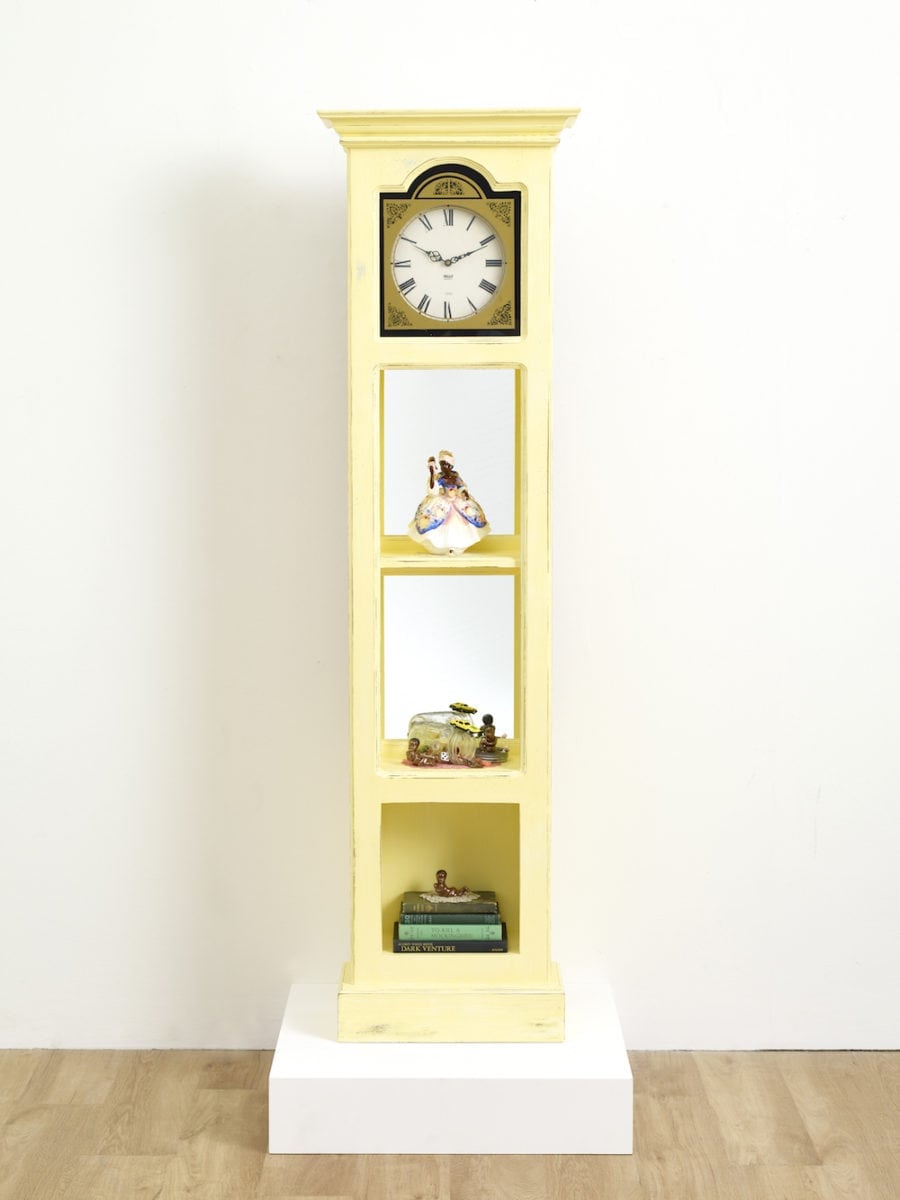

There are, of course, also physical objects in this show, that more closely resemble the conventional idea of a talisman, juju (as they are known in West Africa), amulet, charm or trinket. There’s Genevieve Gaignard’s assemblage of a grandfather clock, porcelain figurine, books and doilies, which is like a family photo album in three-dimensions, personal belongings that also bear a wider social resonance. It’s in Gallery Two that this part of the exhibition really comes to the fore, with a spectacular wall covered with all kinds of materials with a magical presence: peanut butter in William L Pope’s work, cotton mesh and wood in Irvin Pascal’s, John Outterbridge‘s Dancer’s Charm and Betye Saar’s Dervish meet Melvin Edwards’s welded steel.

Talisman isn’t only about this kind of alchemical artistry. It’s about challenging the western idea of art, including the role of beauty and the purpose for creating. “All of Western art has influences from many other cultures—Picasso would struggle without Africa,” Shonibare notes. “Understanding the debt Western modernism owes to African creativity is a point underpinned by the inclusion of works from the Chapman Family Collection by Jake and Dinos Chapman in the exhibition.”

In Ayahuasca ceremonies in the Amazon Basin, indigenous shamans use a rattle to mark different phases of the ceremony, awakening in turn the consciousness. Shonibare, as shaman, has created rooms of consciousness marked not by the sound of a rattle but the footsteps through the gallery. It is unlikely that just one trip will be enough.