David Lynch I, Los Angeles, USA, 2007

There’s a huge amount of skill in making a well-worn genre seem entirely fresh. It is something Nadav Kander achieves effortlessly in his images. Sure, we’ve seen Kanye West’s face a thousand times, but not like this—the hand of an unseen person grasping at his throat, perhaps an indication that this isn’t a man as in control as he appears, one who is throttled by forces we can neither see nor understand. Significantly, there’s a hint at racial issues here too: the hand apparently throttling him is white, grasping Kanye’s black neck. This work isn’t about people, it’s about society, about the world, and our individual places within it.

Kander’s has a talent for deceptively simple visual devices. There’s both clarity and ambiguity in his images, which makes them feel even more special. The intimacy he achieves with his subjects is unparalleled, but deftly leaves a lot of space for interpretation. He has the ability to elevate commercial commissions into the realms of art.

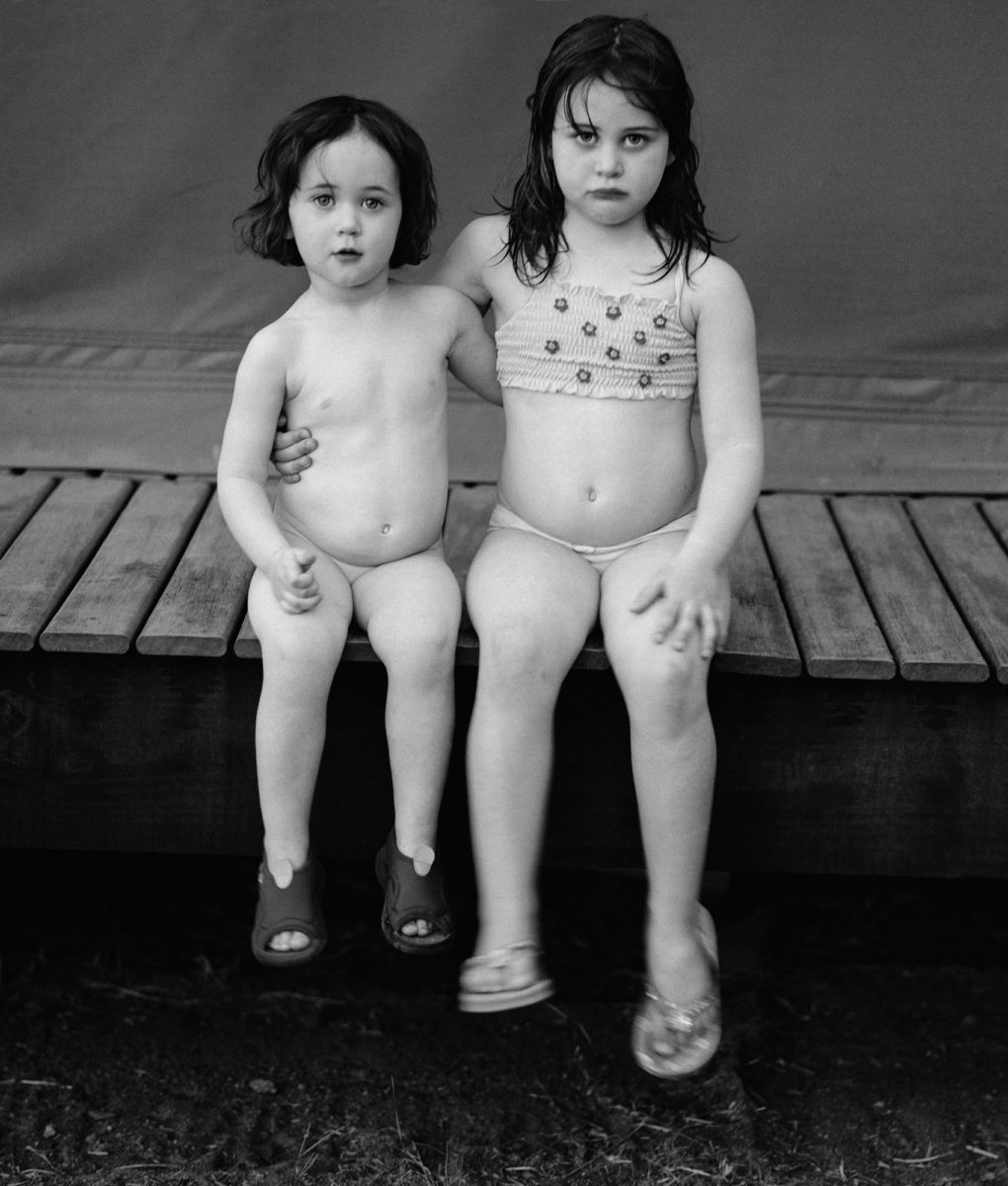

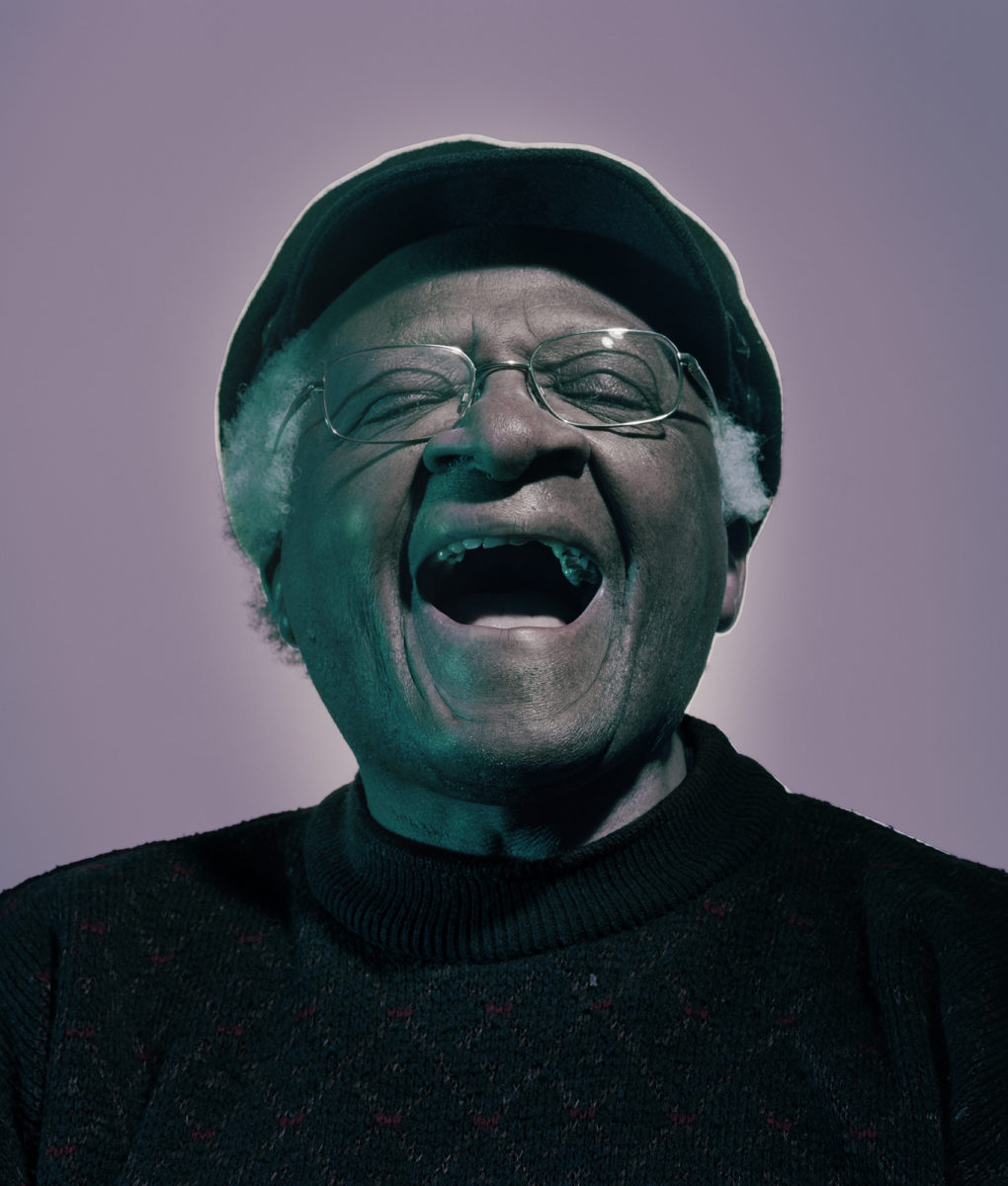

- Left: Werner Herzog III, Los Angeles, USA, 2011. Right: Ella and Talia II, Northern Transvaal (now Limpopo Province), South Africa, 2003

This is all brought to life beautifully in a hefty new monograph of Kander’s work, The Meeting, published by Steidl. Alongside the celeb shots we’re perhaps familiar with, the book also presents more experimental work that demonstrates a profound understanding use of shapes and tones; and a willingness to blur, distort and shift straightforward images into something more eerie and abstract.

“I don’t photograph to tell stories. I photograph to make stories”

Many of such pieces feel rather dark, both in the predominance of shades of grey and defiant chiaroscuro, but also in the feel that there’s a certain discomfort going on behind the faces and poses of the subjects. Many of these images show people looking not at the lens but into the middle distance, at something we as readers, and Kander as the photographer, cannot see.

Whoever his sitter may be and what stature they may hold, Kander’s aims in portraiture remain the same—to demonstrate the humanity within, rather than making a simple documentation: “Revealed and concealed, beauty and destruction, ease and disease, shame and shameless,” as the photographer puts it.

The Meeting seems a fitting title, thanks to both the idea that we’re “meeting” people we’re unlikely to encounter in real life. It’s a glittering roll call with the likes of David Lynch, Paul McCartney, Morrissey, Matt Lucas, Thom Yorke, Desmond Tutu and countless other hugely famous types. But we “meet” them anew, and see entirely different aspects to them. Adam Ant looks gentle and even vulnerable, while the usually impeccably composed David Beckham’s shot is manipulated to look not unlike like a filter-happy fifteen-year-old on Instagram.

“The viewer, if they hold their gaze long enough, becomes the author of the work’s meaning”

But there’s also a sense of revelation in other very intimate works, like a set of images of a woman with a new baby, reclining, eyes shut, against a pure stark white backdrop. Intimacy need not mean faces, either—a shot of the askew clasp of a bra strap tells us so much in a tiny crop of a woman’s back. I immediately think of the joys of taking off an uncomfortable bra at the end of the day, of fumbling sex trying to unclasp old, weathered underwear, of her goose pimples—perhaps aroused, perhaps simply cold.

Designed by Kander, along with Duncan Whyte and Steidl’s in-house design team, the vast page sizes and omission of all text captions makes the images seem even more special—they’re given the space they deserve. Some spreads leave one side completely blank, as though offering the reader a pause before immersing their eyes once more in the details and nuances of a portrait.

“I don’t photograph to tell stories. I photograph to make stories. The viewer, if they hold their gaze long enough, becomes the author of the work’s meaning,” writes Kander in the introduction to the book. He describes his collaborative process with his subjects: “Our stories collide and change depending on the day, the weather, our emotional states.

“If I manage to make a portrait that stirs a viewer then they complete what I call ‘the triangle’ by bringing their own story or state of mind to the picture. This is fundamental to me, but often missed or misunderstood, because photography is still considered by many to be a record of an event. It is that; but it is not only that. How can it be?”