With a focus on the histories trapped in materiality, ‘Ground Break’ challenges our perception of time and space to invoke a state of “spiritual possibility”

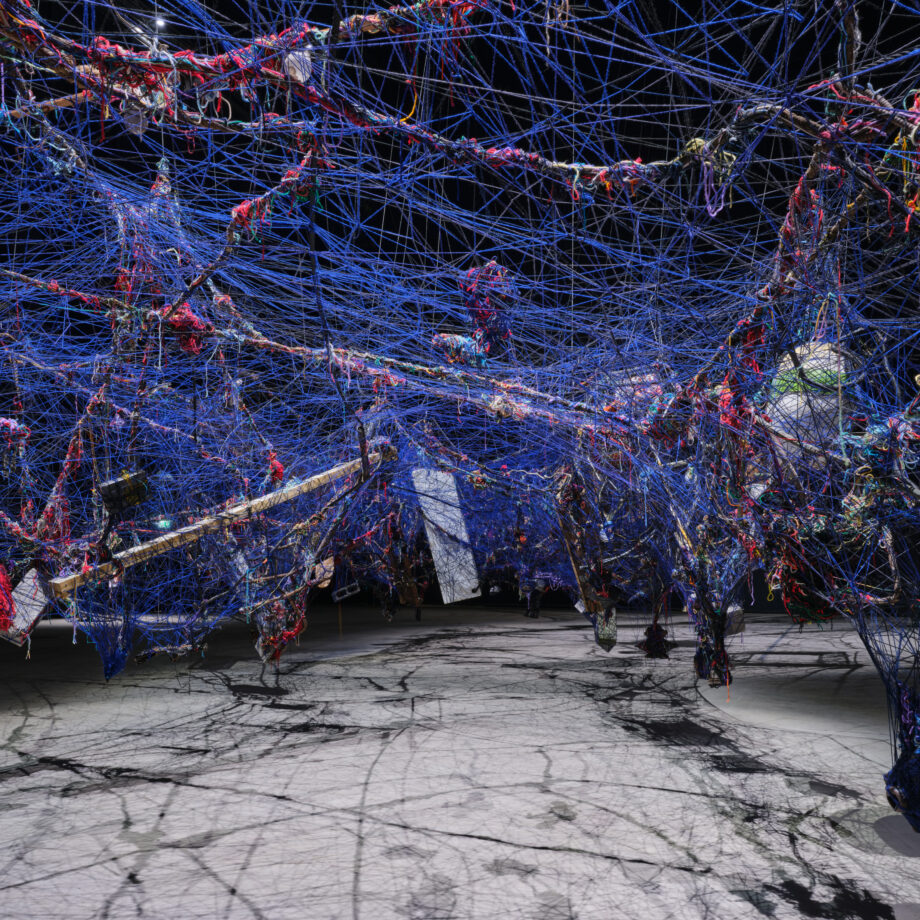

London. Photo by Axel Dupeux

Entering Nari Ward’s newly launched retrospective Ground Break feels like slipping into a den of some sorts: fluctuating over visitors’ heads as they make their way through Pirelli HangarBicocca’s ‘piazza’ – the first room of the hosting institution to be transformed by the installations of the American artist – is a labyrinthine web of yarn, rope and found materials which acts as a portal into his colossal presentation. At once fragile and thickly woven, gossamer-like and interspersed with shopping trolleys, wooden furniture, empty cans and utensils, in dictating the audience’s movements through its fabric constellations, Hunger Cradle (1996-2024) becomes the theatre of a curious rite of passage: left the bright premises of the venue’s ‘shed’ – the antechamber to Ground Break – the public transverses the dimly lit innards of Ward’s piece in line, like in a ceremonial procession. What awaits them on the other end is an experience they’ll hardly forget.

Constantopoulou

Like many of the 26 artworks on view on this occasion, Hunger Cradle was first presented decades ago: its earliest appearance dates from the artist’s 1996 3 Legged Race exhibition, which he co-organised with Janine Antoni and Marcel Odenbach at a former fire station in Harlem, New York. Inspired by “the life of the building”, which since 1916 had gone from serving as a carriage depot in the horse-and-buggy era to being part of the fire department, a piano moving company and a limousine service, the original piece incorporated car parts, fire hoses and a piano. The same principle applies to the work’s new iteration: here, the bricks providing the foundation to Ground Break (2024), the installation from which the retrospective takes its title, hang alongside locally sourced wooden cable reels – a hint at tyre-production giant Pirelli’s origins as a manufacturer of submarine telegraph wire.

Moving seamlessly between past, present and envisioned futures, Ward has carved a prolific career out of lending an ear to the overlooked mythologies still echoing through his objets trouvés. Born in St. Andrew, Jamaica, in 1963, at 12 he moved to New York with his family, with whom he later relocated to New Jersey. His initiation into artmaking came from the pulsating crossroad of cultures of 1980s’ Harlem, where Ward settled in at the end of that decade. It was there, in the so-called “Big Mango”, that he began to mould the collectivity-oriented vision that would come to define his work by tuning in to the reality of immigrants from the Southern US and the Caribbean who constituted the vast majority of its population. A trained illustrator, Ward left the bidimensionality of drawing behind to pursue his affinity with mixed-media installation; an artistic shift which was largely influenced by the urban detritus assemblages of African-American artists John Outterbridge (1933-2020) and David Hammons (Springfield, 1943). Today his art elevates the scraps of consumerism to emotionally charged talismans capable of showing us alternative ways forward.

HangarBicocca, Milan. Photo by Agostino Osio.

Ambivalence, liminality and transformation are only three of the ideas that spring to mind once I disentangle from the knitted tentacles of the artist’s opening piece. Released from the womb-like cocoon of Hunger Cradle, I feel suddenly disoriented in the venue’s ‘navate’ – the largest of its rooms – as if glancing at the world for the very first time. Throughout the show, an impendence permeates the exhibition space: soon I start to pay closer attention to anyone gathering around Ward’s works, the way they move towards them, stop to scrutinise them and wander off into a different direction. I subconsciously try to predict their next move and trace their journey through the enormous black box that is Pirelli HangarBicocca when I come to the weirdest of realisations: no matter how tall or short, young or old you are, let alone where you come from, when looked at against the mammoth sculptures of Ward’s Ground Break, we aren’t but dots – like stars in the sky. It is a feeling I have only ever ascribed to religion, that shared sense of defencelessness before divine intervention. Yet, in the American artist’s own patchworked, litter-made cosmos, there is no fear of God nor Judgment Day but margin for redemption, understanding and new universal awakenings.

HangarBicocca, Milan. Photo by Agostino Osio.

Visitors, I realise, complement the pieces on display, as if their human nature – however distant from Ward’s upbringing and the perspectives voiced in his work – was enough to ignite them with a life of their own. It is a mechanism the artist identified as the very trigger to his production: “it was that desolation around this thing that was part of somebody’s routine and rhythm that resonated and then inspired me to figure out how to tell a story that wasn’t just my story,” reads a quote included in the booklet accompanying the retrospective, which is curated by Roberta Tenconi with Lucia Aspesi. Before being acquired by its current owners in 2004, Pirelli HangarBicocca was an industrial factory dedicated to the fabrication of railway vehicles and aircraft. Much like a train, Ground Break acts like a bridge into another dimension where ordinary objects are imbued with supernatural powers. In its background, people’s whispering voices and careful footsteps seem to merge into a humming, chantlike song; they are the protagonists of an unstaged performance.

Originally conceived between 1996 and 2000 for Ralph Lemon’s choreography Geography Trilogy and showcased here in an exhibition setting for the first time since then, Ward’s Geography series superimposes references to the iconography and rituals of the African diaspora with those to the artist’s own Jamaican heritage. Here, dozens of glass bottles (some empty, some filled with paper drawings) are woven into a totemic beaded curtain which shimmers and undulates in a pas de deux with viewers’ movements. Possibly my favourite piece from the whole show, Geography Bottle Curtain (1997/2024) took me back to the summers spent at my grandfather’s house, when beaded curtains weren’t only a shelter from Southern Italy’s scorching heat, but also a site of play, comfort and love. Elsewhere, a huge swathe of plexiglass, pallets and burnt sugar – a core ingredient of many Caribbean dishes, though inextricably linked to the slave trade in the Americas – are mounted onto a wall in a composition reminiscent of churches’ stained-glass windows. Another one of the disguised thresholds that recur throughout Ground Break, Geography Temperature Curtain (2000/2024) is made of the same PVC strips used to insulate the entrances to butchers’ cold rooms and warehouses.

The sacred and the profane, faith and bodily desire are not at odds in Ward’s decades-spanning retrospective but two sides of the same coin. We see it in his interactive piece Wishing Arena (2013), a towering structure modelled after a votive altar from several ladders and baskets all joined together, each basket containing an electric candle ready to be switched on. Like the title anticipates, the work deals with hope by inviting visitors to whisper their dream into one of the tin cans attached to each of the tealights, while someone else is called to “turn the light on” their wish. We sense it inside Super Stud (1994/2024), the small chapel Ward decorated with a floor mosaic entirely shaped out of salt cod chunks – a pungent alternative to Rome’s traditional ‘sampietrini’ cobblestones – where floating plantains counter the solemnity of the yellowed Madonna and Child icons that plaster its walls.

That the retrospective refuses to engage with religion in its more orthodox sense doesn’t surprise me; after all, Ward’s art has always centred on people, not on any distant God. Across all 26 artworks featured in the show runs a reinvigorating energy which lifts the curtain on the value that lies in the discarded as physical traces of our brief passage on Earth. Perhaps all we need to cultivate our faith is right there; in the human connections that live on in those seemingly worthless remains – be they under our feet, in front of our eyes or up in the air, just like one of the artist’s flying sculptures. All it takes is recognising it.

HangarBicocca, Milan. Photo by Agostino Osio.

It is an observation that rings especially true in relation to the artist’s Ground Break installation, the centrepiece of the exhibition. Developed on site by Ward with over 4,000 concrete bricks coated with copper sheets across an area of 18 x 18 metres, “90% of this work lies underneath its surface,” he explained during the press preview of the show on March 26. Responding to notions of support, fracture and metamorphosis, this square platform reminds us that there are things which, though invisible to the eye, still influence our existence. Spray-painted in varying tones of cerulean blue, the construction’s surface pairs Ward’s footprints with ocean as well as galaxy-inspired spiralling motifs and geometrical shapes obtained, respectively, by using prayer beads and the bricks as stencils. A celestial portrait of the artist at work, Ground Break embodies his ability to gather soil, sky and everything in between under the same “state of spiritual possibility”. Through assimilating clues to its work-in-progress and apparent flaws into the finished piece, Ward rejects sterile perfection in favour of a practice that thrives off chance, trial-and-error and constant renovation.

An activation of Ground Break by Florence-based artists Justin Randolph Thompson and Andre Halyard and Milan-based artist and curator Jermay Michael Gabriel transforms the metallic platform into a gargantuan percussion. It is the first one of a series of events designed to spotlight musicians reinterpreting the materials of Ward’s production through various sounds and instruments across the exhibition’s four-month run. A dense crowd surrounds the work as Thompson’s soulful voice reverberates through the broad chamber of Pirelli HangarBicocca, rapidly spreading across its entire perimeter. He makes his way to the centre of Ground Break while beating an old tin bucket. Within seconds, Halyard and Gabriel join him in a hypnotic progression which, coupling traditional instruments with electronic music as well as ordinary objects, evokes the powerful roaring of waves, thunderstorms and heavy rain. Before the public knows it, the performance comes to an end, the mass gathered around it dissolves. What lingers, though, is knowing that even if just for a moment, I forgot where I was.

HangarBicocca, Milan. Photo by Agostino Osio.

Written by Gilda Bruno