Appearances, as we all know, can be deceiving. If you happen to have walked up Penfold Street in London in the last few weeks, you will have passed by what seems to be a millennial-minded office space: plants, amiable colours, open-plan desk space. Pinned on the wall is a detailed schedule, while a photocopier has a sign reading “I am Here for You to Use”. Inside is a woman in paint-smattered dark overalls—apparently decorating the ambiguous workplace.

This woman in overalls is Navine G Khan-Dossos, and the stage is set to discuss something more sinister than the bright motif of colours would suggest—British government surveillance. Look closer at the details and Khan-Dossos’s whole process is on show: the calendar pinned to the wall showing events and deadlines, ring-bound folders on the desks containing her extensive archive of documents and research into Prevent—the British government’s safeguarding strategy. The transparency—which has included Khan-Dossos being present and available in the space—is also deliberate, a comment on the fact that so much information around government surveillance is concealed and inaccessible.

“I’ve known about Prevent for a long time, and followed its course over the years from a distance”, Khan-Dossos tells me. In recent years, she explains, the experiences of a friend who worked as a teacher in a school in Tower Hamlets brought the reality of Prevent closer to home. “Having previously had a good relationship with his students, regularly debating many subjects in class assemblies, he noticed that when Prevent became a statutory duty, his students stopped talking to him about their concerns.” Following this experience, her friend left teaching, turning his attention to research and lobbying against Prevent.

Prevent is currently statutory duty for seven specified authorities that forms section 26 of the Counter Terrorism and Security Act of 2015. It has been around since 2004 but since then it has had an increasing presence in schools, universities and in the NHS. “Most people working in these spaces will have either online or in-person training, asking them to look out for certain behaviours or traits that could suggest a vulnerability to radicalization.”

“Since its inception Prevent has been highly criticized for been racially biased towards the Muslim community”

Reading over the checklist provided, it’s clear how ambiguous and problematic it could be. “Since its inception Prevent has been highly criticized for been racially biased towards the Muslim community, but also for having a chilling effect on the conversation around radical and extremist politics.”

There Is No Alternative (the title of Khan-Dossos’s exhibition) addresses the concerns about Prevent from a visual perspective—connecting to Khan-Dossos’s ongoing examination of the link between aesthetics and civic duty. Looking at the branding of Prevent over the past fifteen years, Khan-Dossos revealed some startling truths about the way visual communication insidiously seeps into our conscience and affects how we interpret messages.

“As the government never provided a clear design strategy or logo for Prevent (apart from the green cover of the duty document itself), it was left to local authorities, schools and police forces to come up their owns ways of visualizing the duty,” she explains. She spent more than two years researching all of the different logos that had been used across the country for Prevent, even locating the graphic designers behind them to find out more about their process through short interviews—part of the exhibition’s archive materials.

“They aren’t particularly good bits of design—at best they are banal, at worst aggressive and misleading”

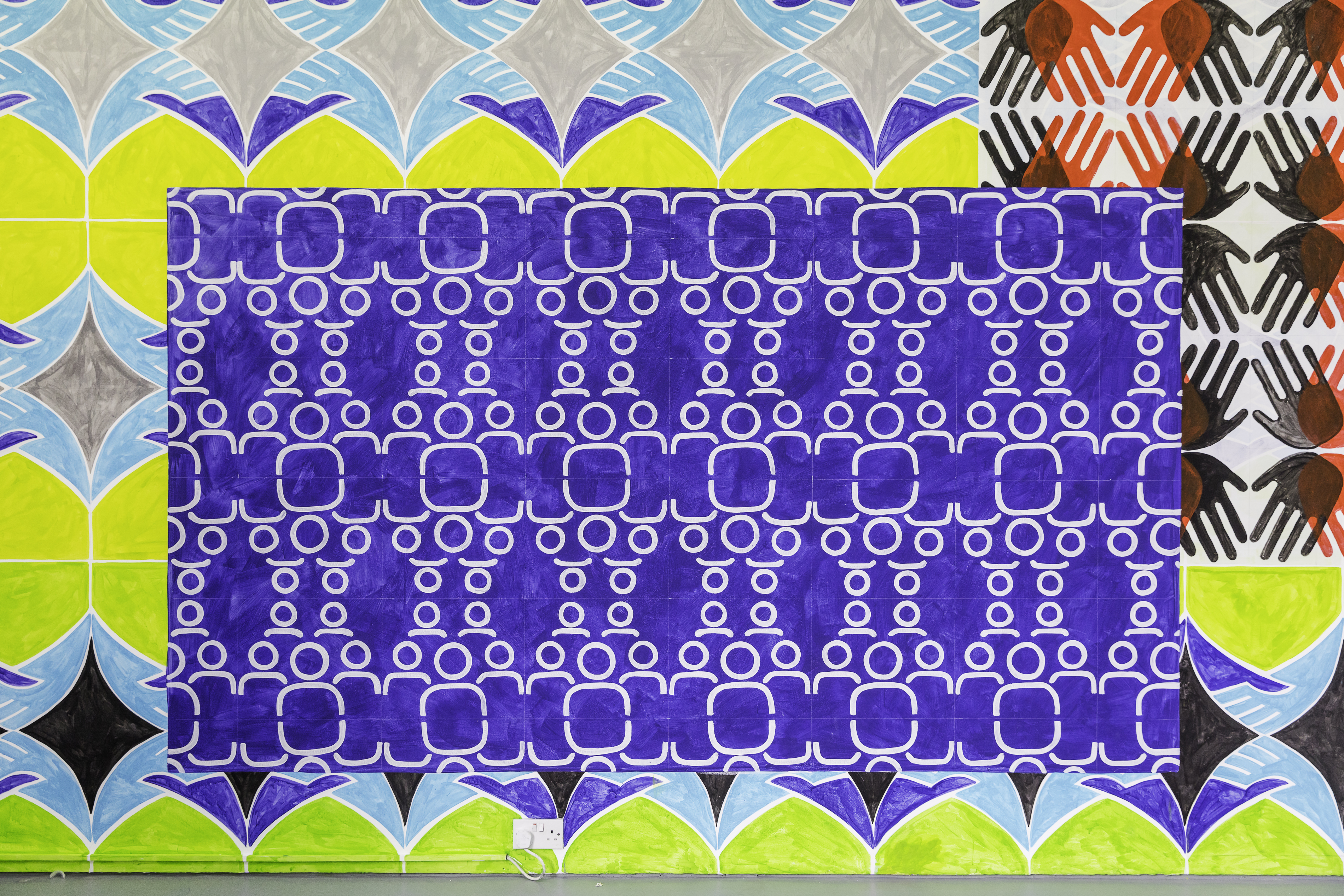

“Many of the logos seems to relate to each other, often featuring hands, which symbolize care, support, protection amongst other significations. It is clear when you look at these symbols that they riff off each other, that they are copied and pasted from the Internet, shared and modified over the years, but the basic language is persistent,” Khan-Dossos explains. “They aren’t particularly good bits of design—at best they are banal, at worst aggressive and misleading. But what interests me about these various on the theme of Prevent is what the bad design reveals about how the policy itself and how it is rolled out with such variation of quality control across the country.”

While the logos would have only been encountered one at a time—on a PDF, website or other visual merchandise materials for Prevent—at The Showroom, Khan-Dossos has painted them in a mosaic-like mural, carefully repeated and painted by hand, and arranged in a pattern to look something like giant moveable screens of information—inspired by scenes in Science-fiction film Minority Report. The visualization of all of the Prevent logos, she says, was “to create a network between these images to show how they actually form an entire system of Prevent across many locations. The logos are calibration targets to show that the institutions they are used by are aligned to Prevent. And when we are surrounded by this, as we are in the show, we can encounter Prevent in a much more direct manner, not as an underplayed disparate strategy.”

There was also flexibility in the mural design to encourage members of the public to collaborate. “This has also been a big thing for me to do—to let go of the ownership of aspects of the work and open it up to be a communal process, which I think, given the subject matter at hand, is key.”

“We need to be able to recognize the much larger framework at play here and understand how these parts bolster each other”

“There is a real ambiguity at the heart of the work, as to what work is being done in this space and it’s up to the visitor to engage themselves with the subject and make their own decisions about Prevent. So the work has expanded way beyond being a painting show, into being an environment that is communally owned, shaped and given life through the ways in which it is used during the exhibition,” she adds.

During the course of her research, “It has become clear to me that Prevent is actually a symptom of a much larger set of issues that we face as a society, which are intimately linked to surveillance capitalism and the many industries that sell the tools and training that are fuelled by the idea of the war on terror.”

In August 2019—a few days after There Is No Alternative closes—an independent review of Prevent will commence. The intention is to find out where it stands today, and how effective it has been—and whether it can “shake its ‘toxic’ image as being akin to community self-surveillance that is causing a breakdown in civic trust and dialogue”, as Khan-Dossos puts it.

Meanwhile, her work was not intended to make that judgement but rather to equip us with the tools to better inform ourselves, both practically and intuitively. “We need to be able to recognize the much larger framework at play here and understand how these parts bolster each other. For me, hearing “see it, say it, sort it” is the epitome of what I’m talking about—a constant reminder to be vigilant, which keeps us all in a low-level state of anxiety in our everyday lives. How can we possibly affect change and real dialogue when we can disengage from this expectation of constant threat?”