There is a photograph by Malick Sidibé that has always enchanted me: it’s an iconic night-time party scene taken in 1963 of young romance, entitled Nuit de Noel. It depicts a young couple in stylish sixties attire, vis-a-vis, almost touching, their heads dipped, lips smiling, with the young woman’s knee-length dress skirting bare legs and feet; opposite her suitor’s trousered legs and loafers. Notwithstanding the heart-shaped outline of their bodies, her poise captivated me the most; it spoke in equal parts to her vulnerability, excitement and freedom of expression.

Sidibé, also a young man at the time and high on the novel power of and demand for his photography, captured this burgeoning sense of cultural liberation, fuelled by Western music. He later said in an interview: “music liberated African youth from the taboo of being with a woman. That didn’t exist before. They liked seeing themselves dancing with a woman, even if she wasn’t their girlfriend. They could tell their friends that they had got her, that she was theirs now”.

Reading these comments and reflecting on the image led me to question the dynamics at play when he shot women. He has a number of stunning images featuring women alone. However, his glaring omission of any consideration of the young women’s perspective, in writing at least, lingered with me.

I had the opportunity to address this concern when Myriem Baadi, founder of Black Shade Projects (a research and exhibition platform) invited me to curate an exhibition of never before seen works by two under-appreciated contemporaries of Sidibé: Abdourahmane Sakaly and Adama Kouyaté. Both artists had amassed huge archives containing a wealth of studio portraits, featuring Mali’s daughters, mothers, sisters, and aunties. They immediately resonated with my curatorial interests in international relations and post-colonial histories, as well as critical and black feminist theories. It was a tantalizing opportunity to empower narratives around the creative and socio-cultural agency of women of the time.

“Both artists had amassed huge archives containing a wealth of studio portraits, featuring Mali’s daughters, mothers, sisters, and aunties”

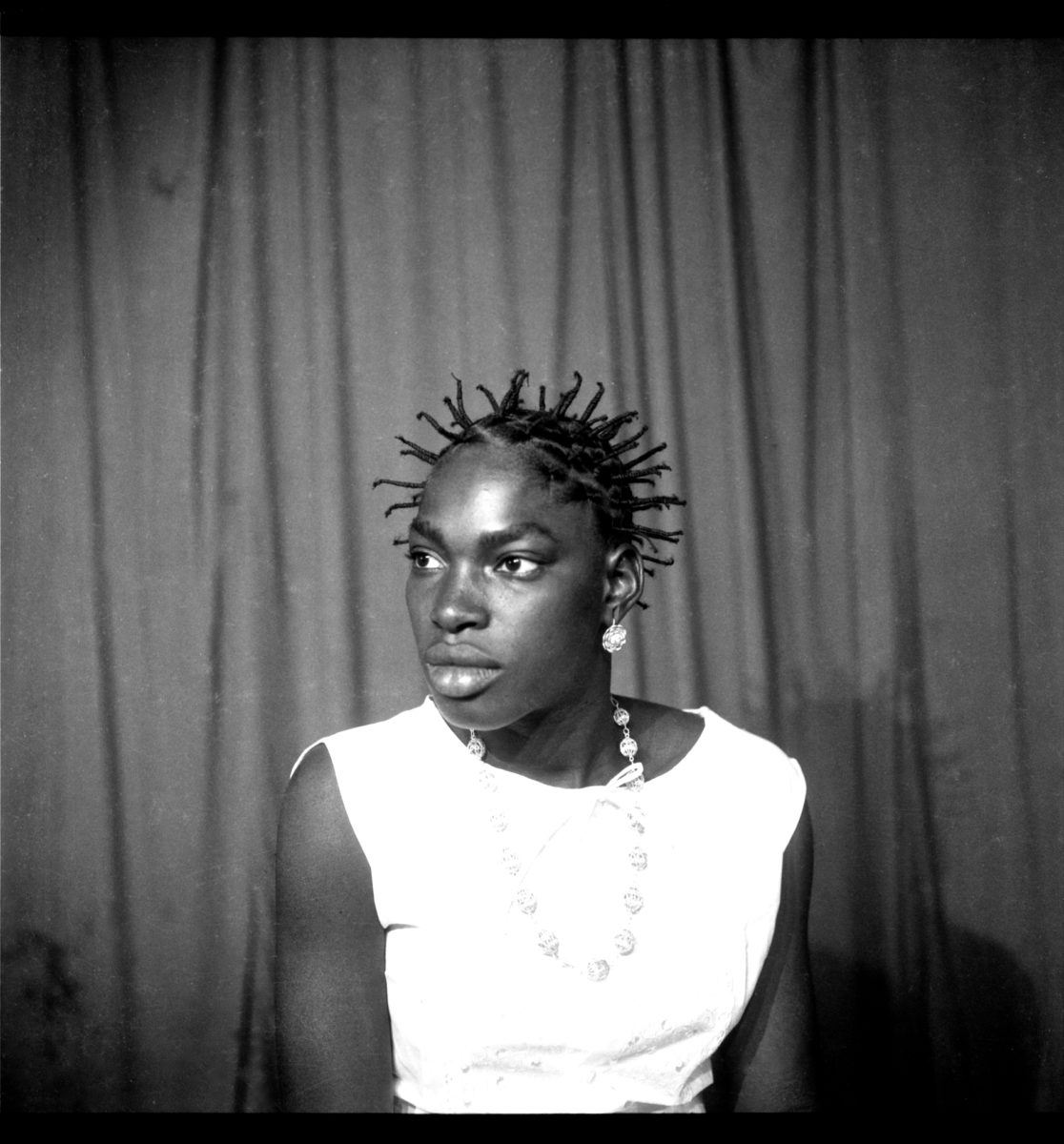

I decided to focus on the power of the African female gaze captured within the archive. Not only would this give me the opportunity to value the women in the frame, question their sensibility, agency and collaboration in creating each image, but it would also give me the opportunity, as a black female curator, to contemplate the significance of each image in terms of the personality, energy and cultural information each contained.

I was also thrilled to be able to continue an important recent thread of curatorial enquiry, thanks to the success of pioneering shows that reclaim and recontextualize the female gaze in under-examined histories of image-making. This includes Sandrine Collard’s 2019 exhibition, The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture, at the Ryerson Image Center in Toronto in collaboration with the Walther Collection, as well as Aunty! African Women in the Frame, 1870 to the Present held at United Photo Industries Gallery in Brooklyn, co-curated by Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Catherine E. McKinley in 2018.

Her Eyes, They Never Lie, the exhibition I curated for Black Shade Projects that took place in Marrakech during 1:54 Art Fair in February, offers three distinct departures. The first is an opportunity to experience a deeper dive into specific African female interiorities, thanks to the show’s comparatively narrow historical and social scope.

“They possessed a compelling self-assuredness, as evidenced in their clothing, accessories, hairstyles, as well as their pose”

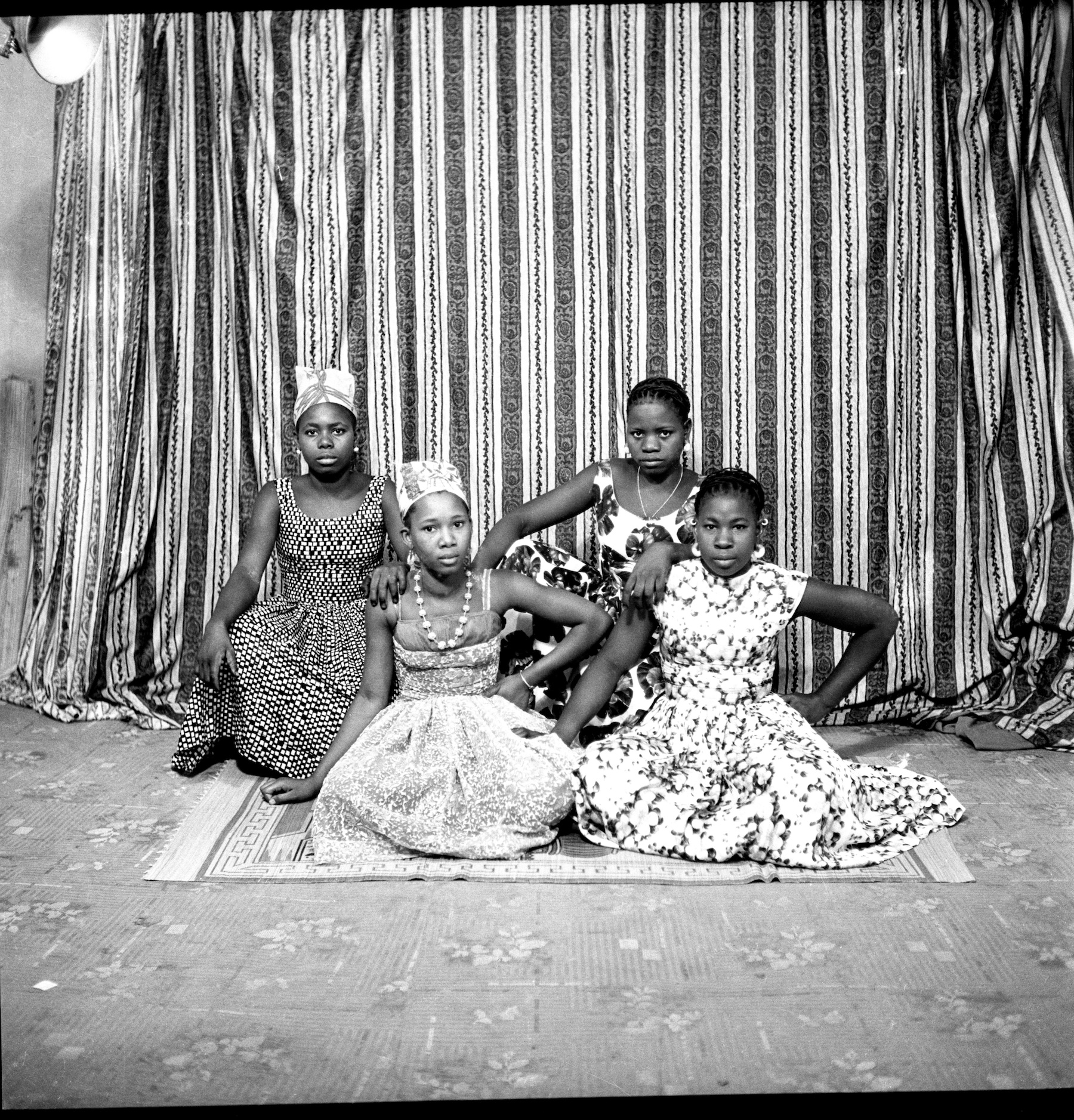

The portraits by Sakaly and Kouyaté (both contemporaries of Malick Sidibé) depict an era in Malian society when the women were privileged enough to enjoy the luxury of studio portraiture. They possessed a compelling self-assuredness, as evidenced in their clothing, accessories, hairstyles, as well as their pose and comportment. This suggests a creative process between artist and subject that was far more collaborative than flattened and objectified readings of these works infer, with each image conveying palpable respect for the social role women played as cultural custodians of a modernizing Mali.

The show also honours a captivating range of personalities, which comments on the breadth of individual style, sexuality and desire they inevitably contain. Whether it’s through the choreographed “aunties” kneeling in train, family and friends tenderly nestled side by side, or solo subjects centre frame, we celebrate in the exhibition these subjects’ capacity for dignified, deeply creative self-expression.