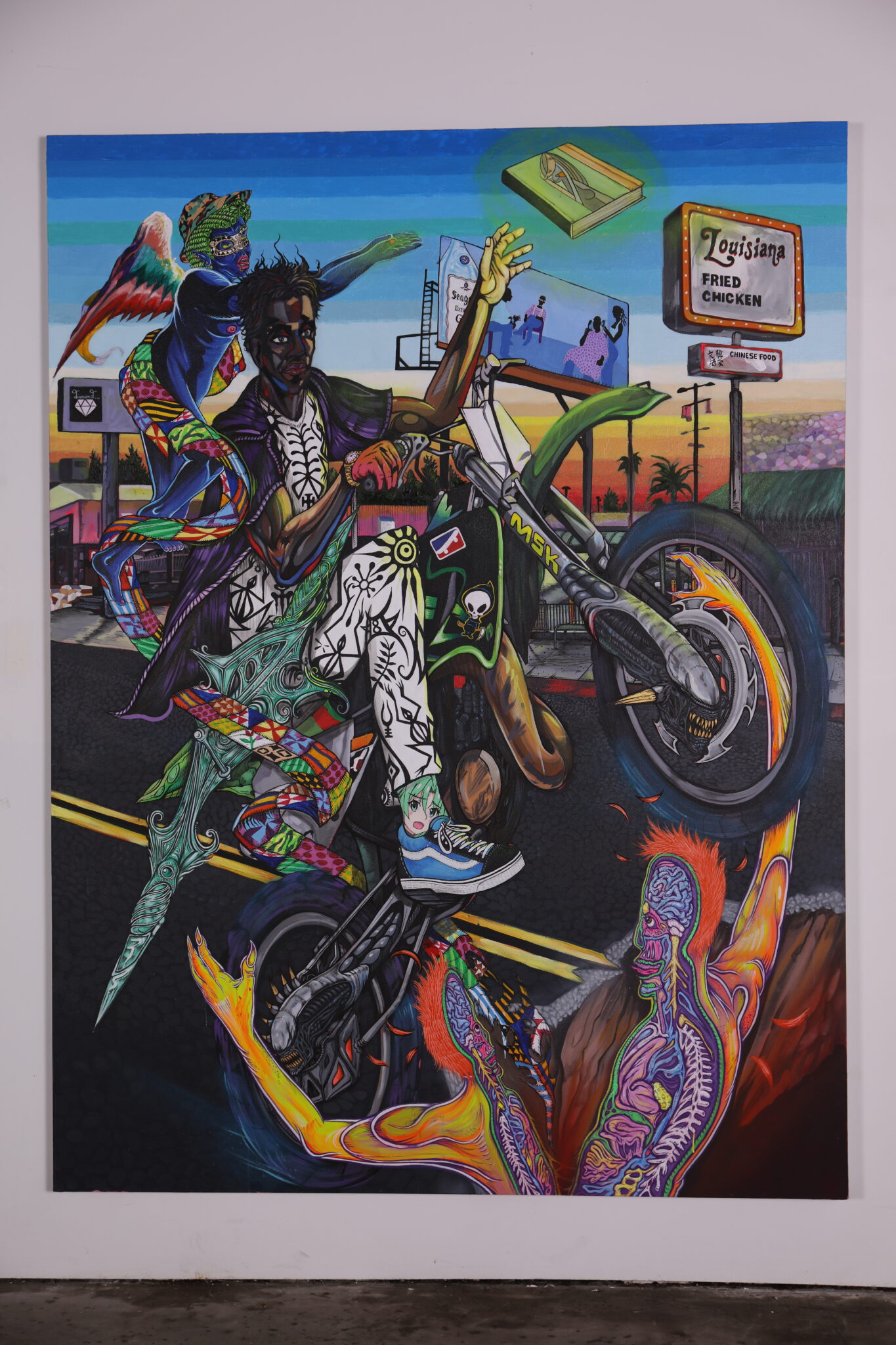

Nehemiah Cisneros conjures Californian epics. The burgeoning Los Angeles painter’s works are markedly Angeleno: fantastically dense, dramatic, Southern California dreamscapes. But they are also clearly the workings of a singular mind, as if through their creation the painter was piecing his personal Los Angeles back together in a fit of nostalgic wonder.

Sitting on the precipice of stardom and at the tail end of a decade-long journey through multiple art institutions, Cisneros has a lot to be nostalgic about. The thirty-seven-year-old artist started his traditional art education at the local Santa Monica College in his early thirties. He then spent four years at the Kansas City Art Institute before getting into UCLA’s prestigious MFA program, which he is set to complete in June. His thesis show Wicked City— a series of narratively related epics which reflect his past— opened on March 7th. This milestone was accompanied by a collaborative exhibition with his mother, a ceramicist, at his alma mater, Santa Monica College, which opened on February 20th, where, in a full circle moment, he is set to begin teaching in the fall.

Cisneros is a prodigal student even by the standards of UCLA’s MFA program, which is one of the best in the country. Over the last few years, he has become one of the most important painters in L.A. and has started to receive professional opportunities that could be ripped off of his professor’s resumes. Notably, Cisneros is coming off the heels of participating at Miami Art Basel last December, when he showed his work at the Rubell Museum as a part of its Singular Views: Los Angeles exhibition, a ceremonial entry into a new life and artistic canon.

Though they are not scientifically autobiographical, Cisneros’s pieces are unmistakably self-referential, ingeniously complex meditations on his past and the histories that contextualize it. To attempt to address all of the ongoing motifs and references in his Wicked City series alone would require a short book. “My paintings are webs that collect my fascinations, memories, and desires,” the painter explained to me over email after I met him at his Culver City studio in front of a backdrop of to-be-completed daydreams.

In the eighteen-foot Wicked City Milestone, which Cisneros describes as reminiscent of Roman Fresco wall paintings and the cumulative piece of his Wicked City thesis show, the half-blue painter watches over a muralistic-ally complex montage on the right side of the piece, picking a spray can from the backpack of a young boy like a mystical Los Angeles deity. This is a homage to his background as a renowned graffiti artist in his early twenties, an artistic period of his life that predated his rise in the fine art world.

(Cisneros in this deity form is a throughline throughout Wicked City. In the first painting in the series, Wicked City 1, which represents the beginning of his journey, Cisneros appears on the left side of the painting as opposed to the right, peaking over the same brick wall, fully blue. The painter in human form sits on the right side, painting a scene from the notorious O.J. Simpson police chase.)

On the left side Wicked City Milestone, the artist poses triumphantly atop a bus bench next to his anointed mother, holding a rolled-up version of Wicked City 1. When I asked Cisneros to explain how his mother fits into the piece, he provided a passionate description. “She is gracefully resting, engulfed in Willam De Kooning’s book, which features a painting on the cover from his Woman series on the cover, and her wardrobe bears patterns of monochromatic Adinkra patterns from West Africa. Fiery wings burst from behind her, revealing bone through the flame. I simultaneously made my mother look angelic and fierce.” The image of the bus bench is also of personal significance. Cisneros still doesn’t drive, a uniquely formative part of his Angeleno experience that has given him an intimate perspective on the city’s geography that most long-term L.A. residents don’t have. Wicked City Milestone thus serves as a representation of Cisneros’s journey— a mythological distillation of his own reflection.

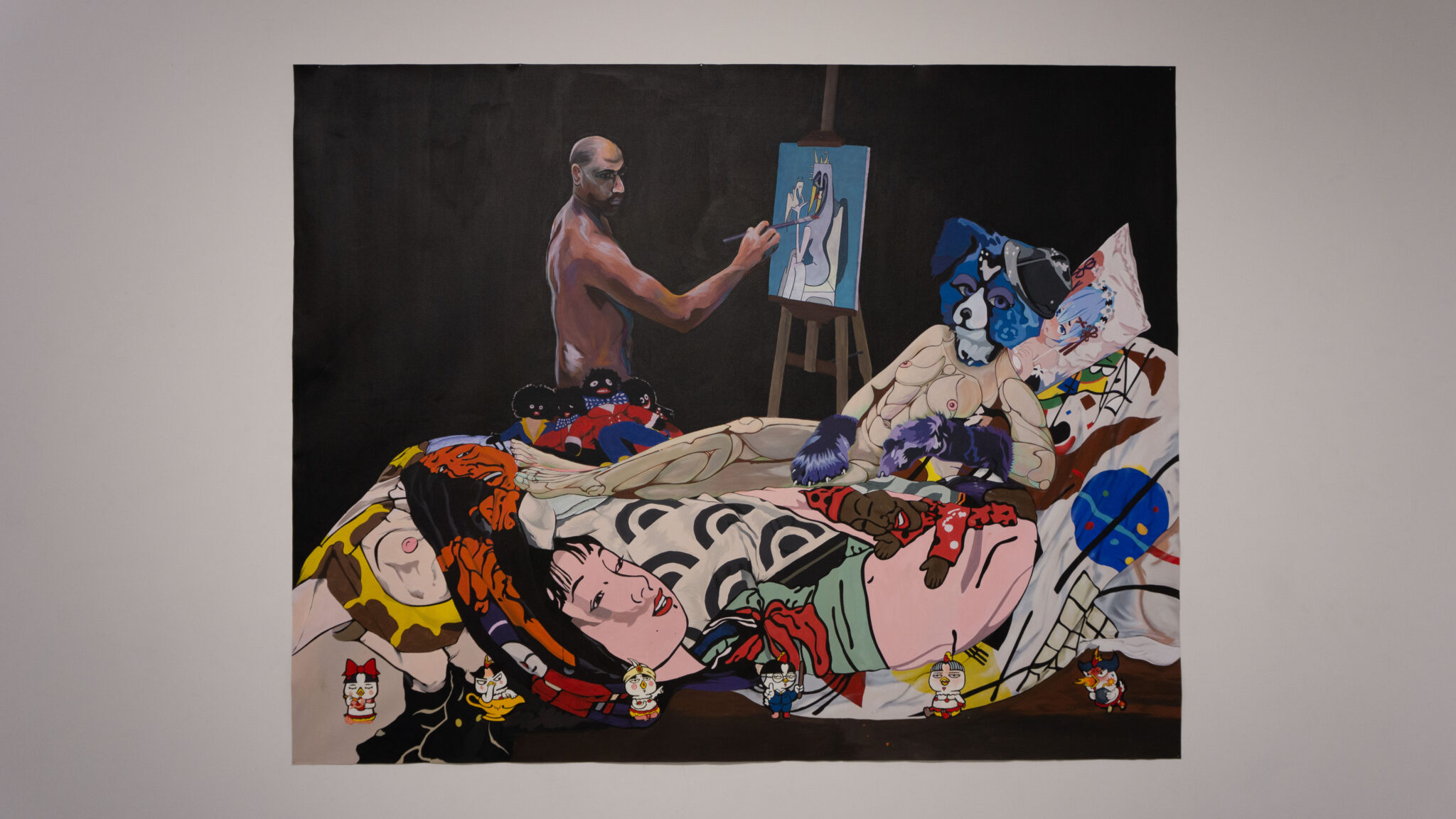

In his piece titled Olympia’s Fursona, a recreation of Manet’s Olympia, the painter stands amongst a mound of jim-crow era Golliwog dolls, working on a portrait of a Furry goddess who lays in front of him atop a cot lined with anime-themed bedding full of racialized caricatures, In a surreal, horror-esque twist, this takes place amidst a blackness that folds into and out of the racialized dolls he stands upon. Notably, the portrait Cisneros is actually painting; however, it is not a furry woman but rather what appears to be a modernist-style portrait of a woman in a bird mask.

The layers of this work and its relationship to history are so open and plentiful that I feel it best to attempt to address it in questions. Perhaps Cisneros could be comparing the furry mask to the masks modernist painters like Picasso utilized to help abstract the human form. Could this be further complicated by this history being a product of the co-opting of African artistic stylistic influences like the mask, which was in many ways related to and rooted in racist, fetishistically colonial notions of “primitivism?” How does this relate to the caricatures that line the bedding? One thing is for sure: the presence of the Furry adornment is a product of Cisneros’s impulse to memorialize the subcultures which he finds interesting, not to make fun of or satirize them. “The appearance reads comically and understandably, yet I am cataloguing the subculture’s relevance, not exploiting the subculture as a joke. I’m logging my fascinations in my paintings, and the Furry Fandom is one of them.”

Cisneros’s self-referential approach does not allow him to shy away from the social realities that have constructed his life. One of the many imagistic motifs in his practice, the subtle yet ever-present image of Jim Crow-era Golliwog dolls, is a relic from the painter’s early years. “The Golliwog doll exists as a trauma-induced guardian angel in my life. I say that based on the history of my mother’s collectable store, The Collectors Safari. The store exhibited a plethora of antique black Americana; among those were the Golliwog dolls,” he recounted. “My work is a conduit of the visual stimulation my mother’s collection had on me during adolescence.” During the 1992 Rodney King riots, his mother’s store was burned down, yet the dolls survived and left a lasting impression on the painter. “I remember staring at their lifeless black eyes as I fell asleep throughout my teenage years until I moved out at 20. The fact they survived the fire and are now on the fireplace of my current apartment is a testament to what my mother and I have overcome, a symbol of our journey together.” The philosopher Susan Buck-Morss, interpreting Walter Benjamin, once wrote that philosophical/artistic perspective develops “only in the sense that a photographic plate develops: time deepens definition and contrast, but the imprint of the image has been there from the start.” This rings true in Cisneros’s work.

Like many Californian youth, Cisneros was influenced by the stylings of film, manga, anime, and comics at large. “My introduction to comic books was through the Shonen Jump magazines of Japan in the early 90s as a kid going to this Japanese Char Broiled Barbeque restaurant called Kuishimbo,” says Cisneros. “They had a bookshelf at the bar containing volumes of Shonen Jump books from the 1980s. These books contained manga printed on colourful newsprints. Upon each visit to Kuishimbo, the owner blessed me with an issue of Shonen to take home after my meal. The graphic linework in those books remains an aesthetic influence for the appreciation of the contour line that my art represents today.” As an adult, Cisneros has combined these primordial influences with his now nearly professorial knowledge of art history, creating a subtle, temporal conversation throughout his practice. The painter wields this dialogue well, referencing and bringing together influences historically kept separate in astounding ways. In Wicked City 1, for example, he combines the imagery of Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentilesch and one of his favourite scenes from the movie Robo Cop.

Film has had a profound and ever-developing impact on how the painter sees himself, his work, and the direction of his practice. Cisneros tells me the elevator pitch for his work is “Ghetto Mythologies, as if Boyz N The Hood Met Lord of The Rings,” and it makes sense. As his practice and artistic outlook have continued to grow in popularity and scale, the painter has found himself in more directorial roles, overseeing two assistants, Grant Blades and Alex Mihaiko, who, in the painter’s words, are “immensely talented artists in their own right.” As his exhibitions become more professionalized, Cisneros has also been given more curatorial space to explore narratively inclined exhibitions and large-scale works. He describes Wicked City as a kind of stage play and the true beginning of his art practice. “I’m preparing for expansion,” the painter says.

What Cisneros will do with this evolving outlook and capability as he transitions from student to full-time professional is unclear. However, it is certain that it will be characteristically epic, likely canonical, and incredibly well thought out. “It’s a bit confusing doing both career and school simultaneously, solely because of scheduling; every project feels like it’s on a shot-clock right now, “get this done before crit” and “get this done before a meeting with a professor,” he reflected. “No one says I have to; that’s all me putting deadlines on myself. I like to have things finished when it’s showtime!” This much is obvious.

Written by Theo Meranze