Antwaun Sargent originally wanted to be a lawyer, a career that got sidetracked after a profound encounter with the work of Mickalene Thomas at The Brooklyn Museum. Sargent gained a new sense of identification that spoke to his own upbringing through Thomas’ elaborate depictions of African American women that examine beauty, sexual identity, femininity and power. A fascination with artists began as he slowly became part of the art community in New York and found expression through writing and curating. “I noticed the lack of conversation in our culture pages about emerging black artistic production”, he tells me. “The New Black Vanguard is part of my decade long journey thinking about their concerns in a serious way, putting them on the page and now in exhibitions.”

The New Black Vanguard is Sargent’s first book. Published by Aperture, it charts a new generation of young black image-makers who straddle art and fashion with a broader set of intentions through artist profiles, an essay by Sargent and conversations with Shaniqwa Jarvis, Deborah Willis—and Mickalene Thomas. An exhibition of fifteen artists of the included in the book is also currently showing at Aperture Foundation, New York. Moving away from the traditional pursuit of glamour, the artists of the New Black Vanguard are telling stories of social and political inclusivity, advocating for a wider celebration of beauty and the self—a powerful antidote for a group previously marginalised in mainstream fashion and culture.

“It was my hope that the reader would be thinking about the ways in which representation almost silently plays on our psyches and shapes our realities,” he continues. “All of our conceptions of who can be beautiful, who can be sexy, who can be powerful, what’s feminine, what’s masculine, all of those things are shaped by the images we experience, and most of the images are taken and created by white men.”

“All of our conceptions of who can be beautiful are shaped by the images we experience, and most of the images are created by white men”

The potent shifts in tech and distribution have been a critical enabler for this movement. Social media has allowed the artists to build their own audiences, overriding gatekeepers and circumventing the traditional pathways into magazines and museums. The addition of their voice to visual culture has been on their own terms, telling their own stories rather than being prescribed a narrow field of opportunities, often shaped by bias and institutionalised racism.

Some are pushing further and seizing the means of production and distribution: Campbell Addy’s Nii Journal and Jamal Nxedlana’s Bubblegum Club were born out of a desire to not only disseminate their work independently but to provide platforms for other marginalized creatives. One thing Sargent is quick to correct is the misconception that change has come from the mainstream. “The reality is that these artists got where they are from doing the work, building their audiences and largely rendering these institutions irrelevant.”

What immediately strikes me about the artists featured in The New Black Vanguard is how unapologetically authored their work is. It’s something that’s lacking in the wider photographic landscape, where the sharing economy has played a role in homogenizing aesthetics and ideas. Nadine Ijewere is known for her portrayal of women of colour in lush and magical environments; she uses joy as a powerful act of resistance.

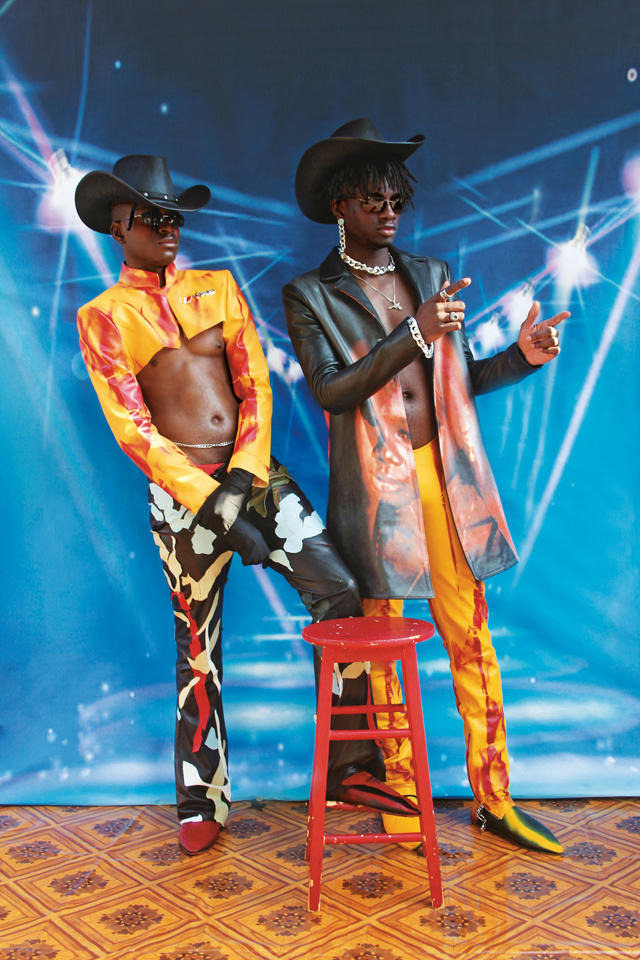

Micaiah Carter’s central influence is his father and the scrapbooks of his stylized life from the 1970s during the Black is Beautiful movement. He blends this with the optimistic futurism of music videos from the 1990s and early 2000s. Laden with cultural codes, the minimalist sets, vibrant colour combinations and warm light give his work sophistication beyond his years. From the outset, Carter is clear about his intentions. In the book, he tells Sargent: “I want my photography to be a quality platform for the representation of people of colour that hasn’t been seen before.”

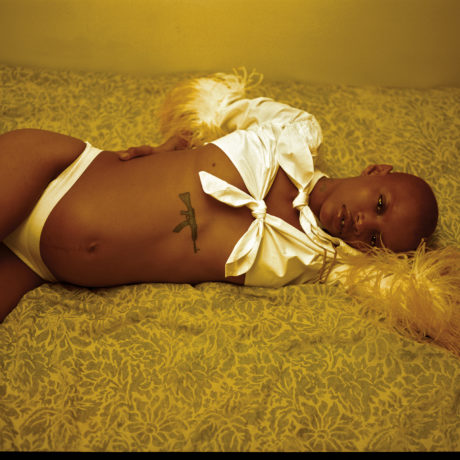

Bronx native Renell Medrano, meanwhile, is not interested in limiting her vision to the highlights reel; flaws and imperfections inspire her. She’s thinking about spaces, intimacy, and vulnerability; styling is secondary. It is unique work that also serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of telling our own stories.

The New Black Vanguard becomes much more than a photo book: it carefully considers the politics of art production and how its evolved over the last few decades. “I knew it had to be about what was new, of this generation, but as a way to look back and a way to think about the future. I wanted the book to take history and show us the fruits of that history. That’s why you have these dialogues between the older and younger generation,” Sargent explains. One of the most powerful conversations in the book is between Renell Medrano and trailblazer Shaniqwa Jarvis, who share their experiences of working as black women within the commercial industry.

The book opens with a quote from Thelma Golden’s 1994 essay “My Brother”: “There is no question that representation is central to POWER. The real struggle is over the power to control IMAGES.” Sargent’s own essay is focused on recontextualising art history, taking stock of the rich visual history of black artists that has existed since the advent of photography. Artists like James Van Der Zee and Anthony Barboza, who suffered widespread discrimination, are recognised for their contribution to capturing fashion images in the early twentieth century.

“I’m interested in charting not only the differences in their practice, but in how ideas of blackness, sexuality, and portraiture have moved or transformed over the course of the last few decades within the black community,” he tells me. “Yes, it’s about the black body’s relationship to the broader culture, but it is also about the black bodies relationship to itself. How might our own inner community conversations have shifted over the decades? I wanted to create a space to have both of these things.

“I’m interested in how ideas of blackness, sexuality, and portraiture have transformed over the last few decades within the black community”

While Sargent unravels the significance of decades of black artistic contributions and celebrates the accomplishments of a new generation, he also highlights the damaging reality of exclusion. The book reaffirms the real responsibility that comes with creating and commissioning photography—a privilege that many overlook. “I wanted to establish right from the start, that we are going to take seriously the way that images have shaped us. The way images operated on us to give us both positive and negative outlooks on the people we encounter, on society, and on our relationship to power.”

The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion

At Aperture Foundation until 18 January 2020

VISIT WEBSITE