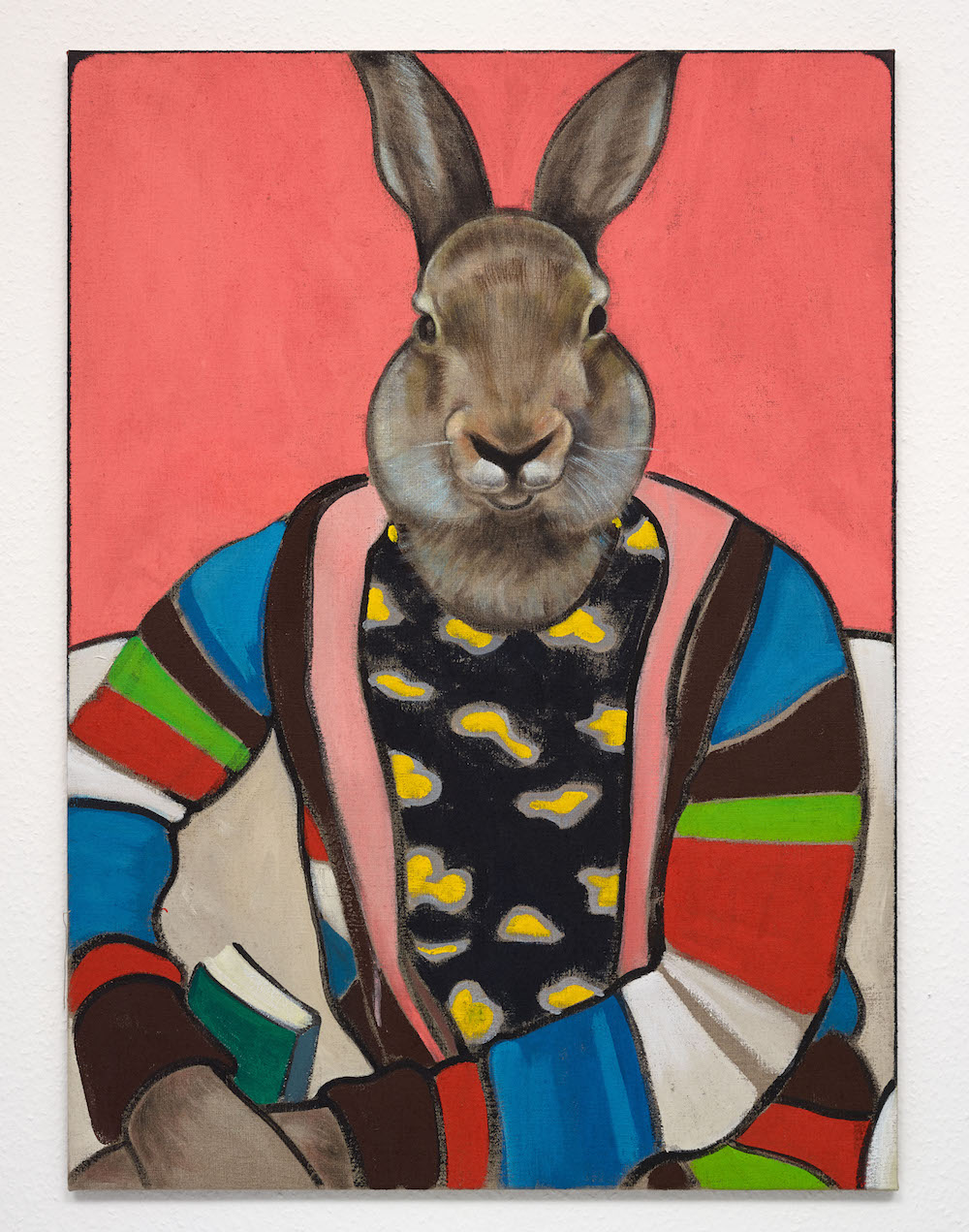

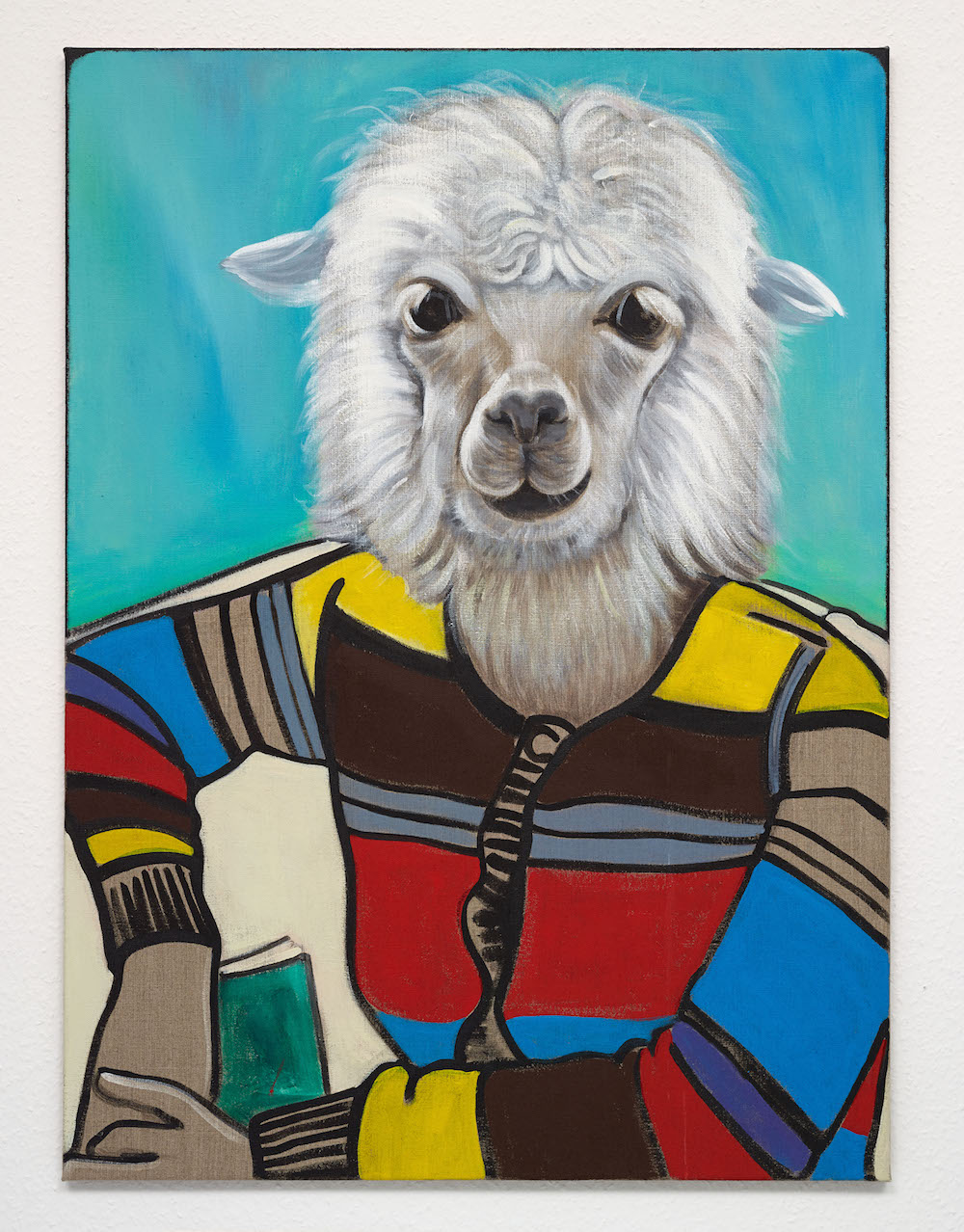

Cornelius Quabeck’s playfully unsettling portraits are suggestive of fragmented identity and fluid sexuality. Animals also figure in his world, sometimes in civilized semi-human guise, highlighting human savagery, and at other times peeping through the layers of his palimpsest-like landscapes. The German-born artist is currently based in Glasgow, where, awaiting a studio, he paints in his living room, a lesson in spatial discipline that sometimes involves accidentally kicking a bucket of white paint across the floor. Words: Muriel Zagha.

When did you become interested in hybrid human/animal pictures?

I have always been interested in the idea of identity. In 2002 a friend recommended Giorgio Agamben’s book The Open, which focuses on the history of man and animals. Where do you draw a line between the two and why? The zoologist Carl Linnaeus boiled it down to man being conscious of being a man and not an animal. I was also reading Will Self’s Great Apes at the time and decided to create some drawings that would describe human/animal hybrids. I used crosshatching to create drawings with a scientific feel, like an illustration in a natural history book.

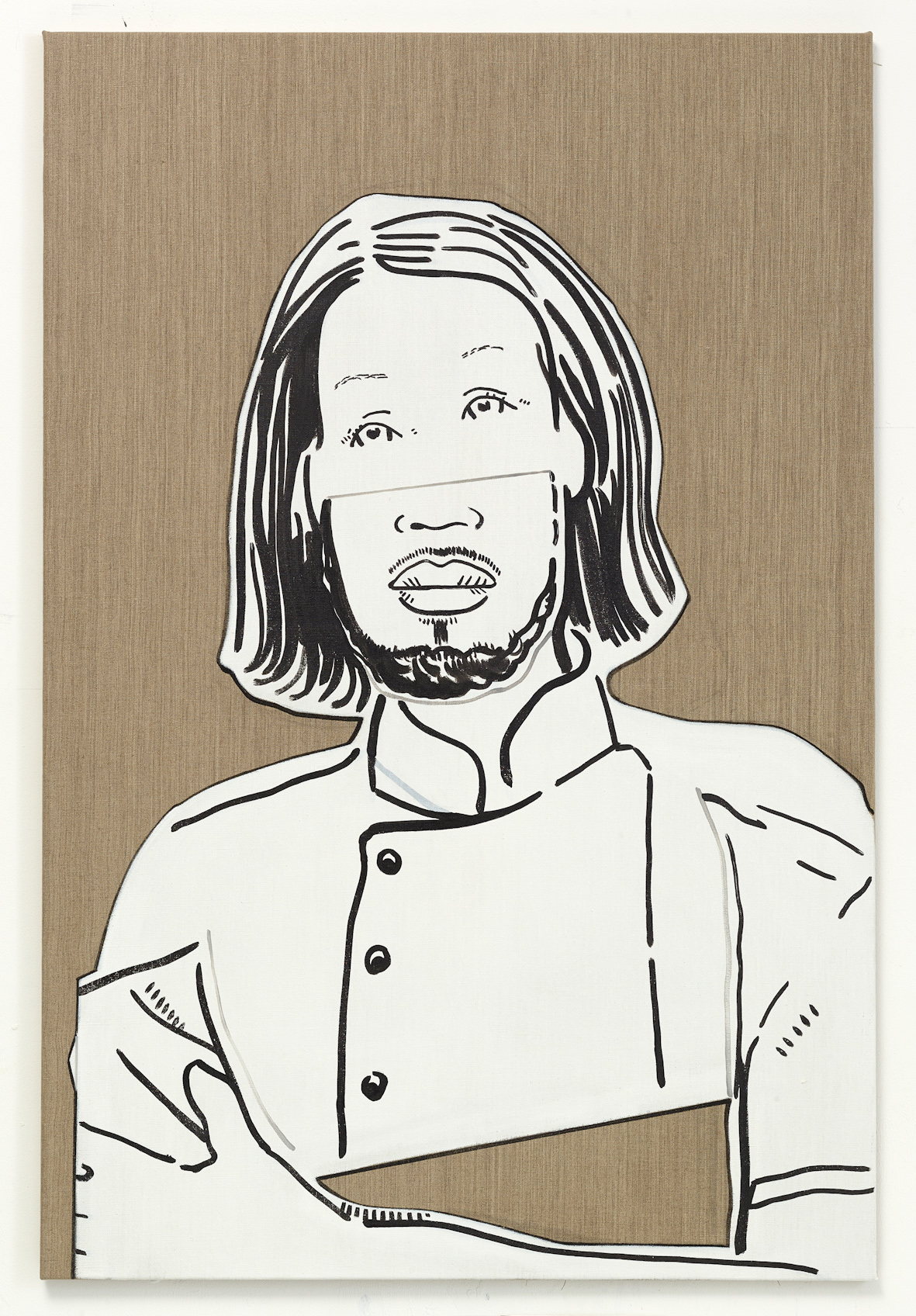

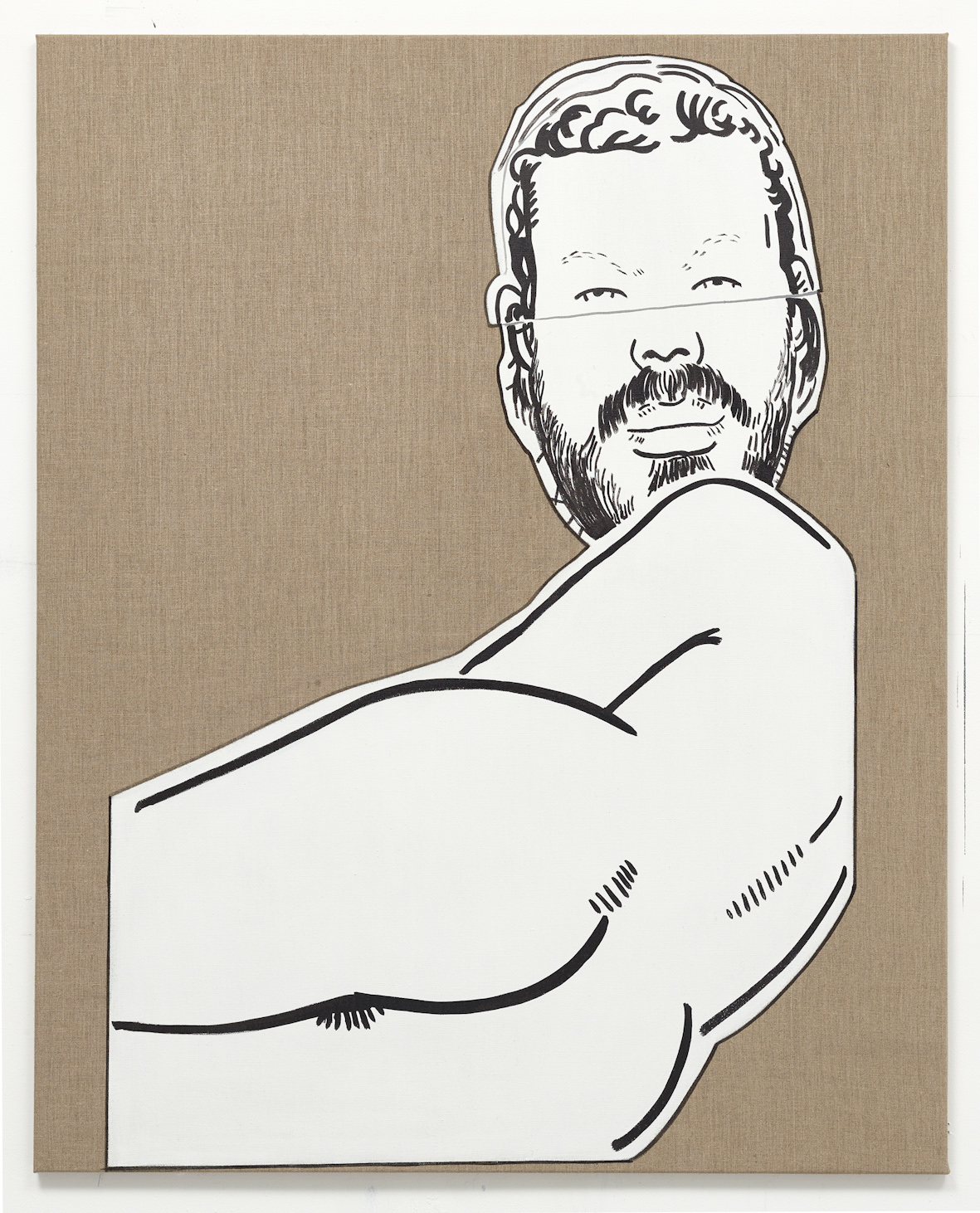

Can you tell me a bit about your interest in fragmented figures (with features and limbs almost as props) in the Unsex Me series?

‘Unsex me here’ is a quote from Macbeth: it’s Lady Macbeth asking to become a warrior. If she can trade off femininity for masculinity she will be able to fight. She wants to be what she is not. The paintings are based on collages made from discarded portraits of various people. From these collages I created new fictional characters that defy the simple male/female binary difference. Nowadays, there is a rising social sensitivity that allows us to discuss identity and gender more openly. We have come to realize that we need to change our use of language to overcome sexism, racism, stereotyping. Facebook uk now allows users to choose from 71 gender options, which I much prefer to simply choosing between yes or no, black or white, zero or one, male or female. A response to the world’s overwhelming complexity might be to develop a more complex identity. With these paintings I playfully visualize what these identities might look like.

Has German Expressionism been an influence on your practice?

This was the kind of art I grew up with. We would see works by Beckmann, Nolde, Dix whenever we went to a museum. My family didn’t have many books on art but Nolde was a favourite of my mother’s and I basically nicked it from her and put it in my bedroom. In 1995 I enrolled at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf after seeing Jörg Immendorff’s Lehmbruck Saga at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne on a school trip. I liked the work because it was all colourful Neo-Expressionism in the manner of Beckmann. My heroes back then were Richter and Polke but I soon got tired of Richter’s cynical approach. Then came Kippenberger and I found out all about the Oehlen Brothers, Georg Herold, Werner Büttner.

Can you tell me about your nature paintings with subtly ‘submerged’ animal figures (such as the dodo)?

In 2009, after moving back from San Francisco to Düsseldorf, I felt stuck. For years I had been using material that I had not really generated myself (photos, flyers, jpegs from the net, record covers, ads, you name it). So I decided to try and create images based on the process of painting, on the ideas and solutions you might come up with while working in the studio. My first works back then were heavily influenced by life in California. While staying with a friend in Marin County, I woke up in the night and looked out of the window straight into a huge fig tree. Something furry was jumping from branch to branch feasting on figs. Our host was trying to save the fruit by throwing her books at what turned out to be a raccoon. The next day she came back from the garden with a bunch of books. That raccoon must have been a quick and experienced reader. I believe this is where the submerged animal figures originated. I made the dodo paintings because it’s an extinct animal with almost no images of it, apart from Jan Savery’s 1651 painting. Fascinated by this, I decided to paint my version of a dodo. In one of the paintings the bird wears a helmet for extra protection. I believe it was [art critic] Martin Herbert who, in reference to my work, called the dodo ‘the poster boy of extinction’.

As an artist you are yourself, to an extent, a hybrid product of a dual influence: German and British. How do you position yourself with regard to both of those artistic/academic traditions?

I was a student at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf with its system of classes led by an individual professor (Jörg Immendorff and Albert Oehlen in my case) and I also took an ma in Fine Arts at Chelsea College of Art and Design. To this day I think it was rather brilliant to be able to experience two very different approaches to teaching art. It did confuse me somewhat in terms of my identity as an artist as I was very much in awe of Cool Britannia and the ybas when I was a student in Germany but in London I was seen as a ‘German painter’, which took years to get accustomed to. I’d still rather think of myself as European.

Spitting Image 2013 Acrylic on canvas 110 x 80 cm