Luke Butler’s deceptively simple-looking, densely coloured paintings riff on ’70s masculine stereotypes from tv or restage cinematic tropes in order to see beyond the two-dimensional frame. The tidy world of the screen becomes subject to scrutiny—the American artist’s way of ‘teasing reality out of artifice’, he tells Ellie Howard.

This feature was first published in Issue 26.

How does an image come about? Do you work directly from stills?

I am fortunate to live in a city on the Pacific Ocean. The beaches and cliffs of San Francisco are vast, humbling spaces that I can never see enough. I take pictures in search of imagery that will look and feel iconic,asifitwerealreadyinafilm. As I work through a painting, I will often go back out to the water to observe the constantly changing colours and atmosphere. I am creating a pop narrative out of my own world. It is somewhat the inverse of my earlier, television-based pieces, where I mined existing narratives for moments of humanity and vulnerability.

You previously mentioned that your childhood was largely informed by TV. How has your youth shaped your art?

There were some pretty regular conversations between my mother and me, when I was very young, where she wanted me to under- stand that the things I saw on tele- vision were not real. Star Trek was on tv every day after school. I par- ticularly admired Captain Kirk, who never had to ask anyone any- thing—he barked orders and did as he pleased.That, exactly, is what my mother didn’t need out of her five- year-old. In later years, Star Trek was still on, but now I watched it at 1 a.m. I was impressed that I still appreciated it, and I had friends that did as well—those are connections that are very real, and quite significant. And that is where my work comes from.

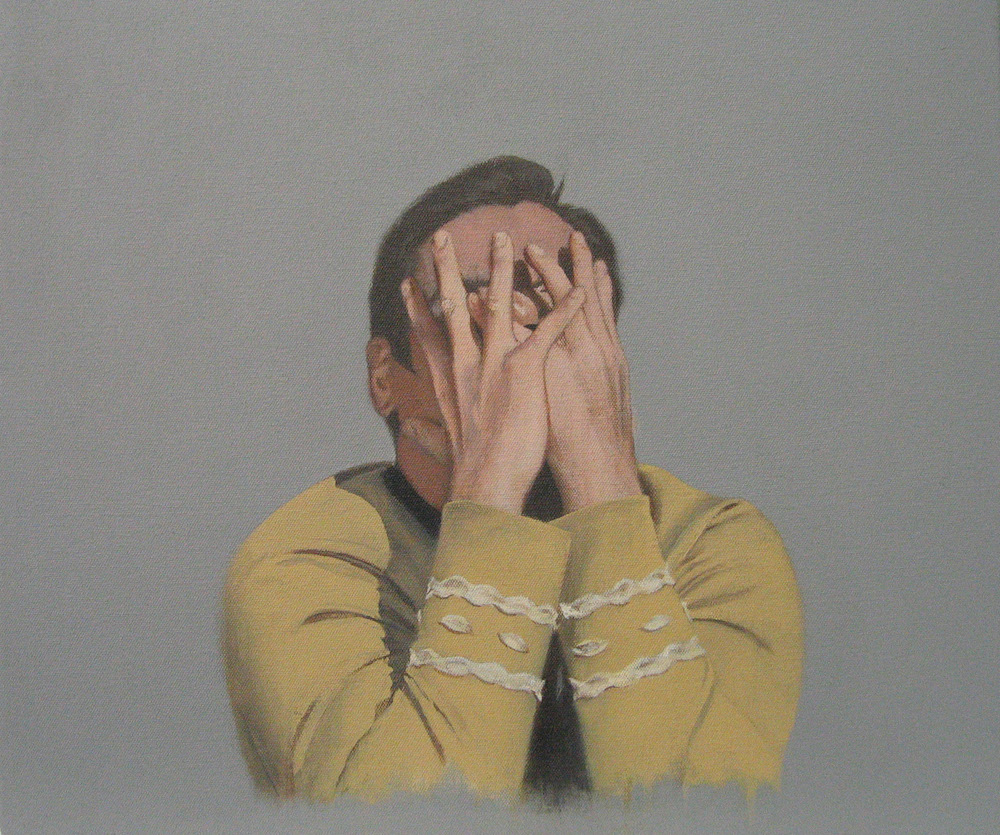

Why do you feel moved to go back in time and show a softer side to iconic alpha-male characters such as Kirk?

Even though I love the idea of decisive, heroic action, it is not really what life is about. So much happens by chance or accident. Clear-sightedness and understanding come later, if at all. The struggles of the hero, particularly one as vivid and wonderful as Kirk, are as meaningful as his triumph. They present a moment where narrative and reality intersect.

In the end series, you seem to be creating stills from a cinematic production of your own—you even credit L Butler Pictures. Are you playing the artist or auteur?

These paintings are intended to look and feel like real movie endings, but they are entirely made-up pictures that I take from the world I know. L Butler Pictures is a true statement, and it gives me a chance to sign my work right in the middle of the canvas. I treat the text as a figure in a landscape, and while this is not actually natural, it is very natural for us to see it there. The preposterousness of these words and gestures is especially appealing to me. L Butler Pictures is both absurd and genuine, which makes for a provocative tension. I suppose I am an artist toying with the auteur.

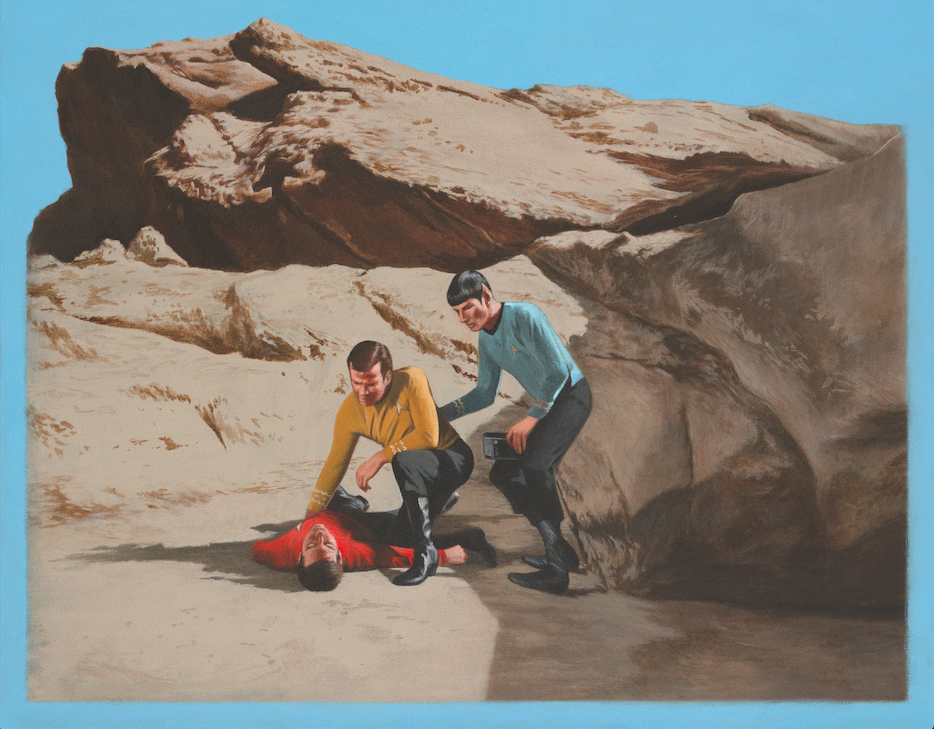

In your appropriated Star Trek scenes, it’s been noted that a figure’s face may bear a likeness to your own. Do you feel a personal affinity with these characters?

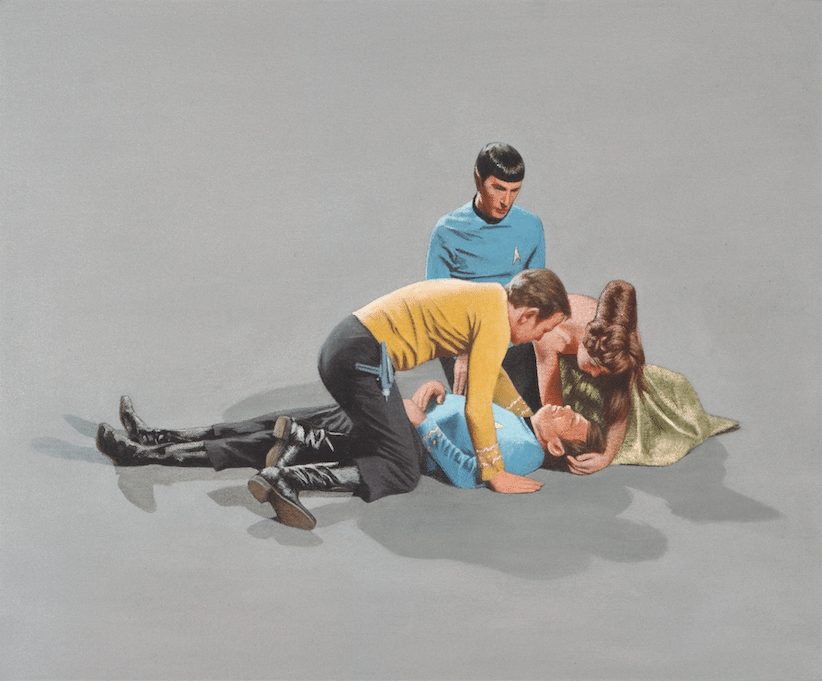

I appear when there is a generic figure that can be replaced. So far it has been as a trivial and disposable red-shirted crewman, whose one moment of significance comes at his end. As in any great mythology, the primary characters in Star Trek are always in the presence of death and danger, but never die. These moments mean one thing in the established narrative context of the show, but another as still images on canvas.The imagery has a classical, even religious aspect—one of enduring pathos and humanity. While I very much want these to look and feel like their original source, there absolutely must be something new in the final painting—an aspect of mortality, anxiety or vulnerability that is significant well beyond the confines of televised entertainment. I am looking to establish the vital connection between the figures in the pictures and we who admire them.

Up close, the paintings are very graphic—a flat bed of colour with layers of increasing complexity and definition. I make a big, gestural mess initially, and work over it in ever smaller and finer steps. There is some wet painting, but also a good deal of hard-edged blocks of pure colour. I want the imagery to be very descriptive, but to sit in a space that is clearly artificial— that is the conceptual thrust of the work.

Would you ever consider experimenting with video?

Why not? It’s good to have a few serious but unlikely dreams. Painting was one of those once, and I’m glad I took that chance.

You’ve painted many variations of THE END, but no beginnings. How would you describe your interest in narrative?

Life is untidy, and beginnings and ends are artificial constructions. I linger at the end for the handsome, compelling joke that it makes. It is a way of at once celebrating and undermining narrative, of teasing reality out of artifice.

‘Luke Butler: Afterimage‘ is showing at Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco, 10 March–16 April

Landing Party II 2009 Acrylic on canvas 66 x 81cm