I meet Mira Dancy at her studio in Gowanus, a Brooklyn neighborhood known for its hideously polluted canal and excellent pie shop. It’s a rainy spring day, humid enough to wilt a stiff sheet of paper, but Dancy is buoyant and expansive on the subject of her newest body of work, still in its early stages. We sit sandwiched between two huge canvases in progress: on one wall is the Egyptian goddess Isis in a garish swirl of colour, and on the other the sketched outline of a figurine reclining in the manner of Manet’s Olympia.

Dancy employs materials and procedures with varying degrees of transparency and permanence, including Plexiglas, neon, paintings on canvas and large-scale wall paintings. She often repeats characters and layers works on top of each other, suggesting recurrence and shifting boundaries. “Each painting is a sort of a ghost of another piece,” she tells me. “The wall paintings and even the neons are all like layers of skin.” She writes poetry while she paints, and sometimes adds words to her compositions: puns, anagrams and runic pronouncements begging to be pieced together like the fragments of Sappho.

When we meet, Dancy is preparing for a show at the Yuz Foundation Museum in Shanghai, slated to open in November 2016. Bringing her work to China means she must adapt her practice to a new set of parameters. I wanted to know how an artist whose subject is almost exclusively naked women would adapt her work to a political context where nudity is heavily policed, if not forbidden.

What’s been your approach to dealing with China’s obscenity laws?

I’m more or less trying to do the show without any naked images. At first I put together a proposal and was told, “This is all great, but you can’t show any images of naked bodies.” I was like, “Why did you even ask me? What do you expect me to do here? What is this about?” Because the show is public, the paintings have to be approved by the Chinese government before they can be sent there.

Did they give you a list of restrictions?

No, I have no idea what the rules are. And I’m the worst [judge] because I don’t think anyone in my paintings is naked—they’re not eroticized in that way. I don’t think of them as bodies; they are so much more about images of images that I think of them in another way. Everything is pushed to a very abstract place. I do think about religious paintings and Catholic ideas of the body being a narrative. Although at some point I’ll have to ask myself, “Is she naked?”

So how does the body become a narrative?

The body is the story itself. With Jesus, the state he’s in, whether as a baby, crucified or dead and an angel, you read images of his body to see what part of the story you’re looking at. I think about of the bodies that I’m working with in that way. I’m into the idea that these recognizable poses are referencing various states of consciousness that can be read on the body. It’s not realistic rendering in any way because it’s not about being real.

“The thing that’s irksome to me is the fucking word ‘female’. Like, who cares?”

Is your training exclusively in painting?

I went to Bard College to study poetry. I’d never painted before, but I was lucky because Amy Sillman was my first teacher and she’s such a generous person. Everything that was unspoken in my young psyche, issues like feminism, opened up through her. I had a lot of interest in architecture but it always comes back to painting as the real motor. From the very first time I painted, I was like, oh my god, this.

Someone has to be in the room with the wall paintings to fully experience their shifting perspectives.

When you’re moving around that room the scale of the image totally changes and it has a different physical operation on the viewer. With the wall painting in [the survey show] Greater New York, when you looked through the archway the figure looked like a youngish woman, but as you walked to the other side she turned into an old woman. The distortion of the face completely changed her. My impulse when making a show is to engage your whole body physically, because that’s a kind of relationship that I want with the figures. I want these bodies to be real enough to suggest that you can occupy or enter them, but not overly so.

You’re a woman who makes paintings of women. Do you ever get frustrated by the discourse surrounding your work or by questions you’re asked during interviews?

Definitely. The thing that’s irksome to me is the fucking word “female”. Like, who cares? I’m fine to talk about feminism, that’s interesting, but categorizing things as “female” isn’t interesting at all. But the thing that I have the biggest problem is the figurative label.

You don’t see yourself as a figurative painter?

Figurative painting is about a painter’s relationship to physical space. What I do is a more linguistic operation, it’s never a figure in space. In my work the background and the woman have a more contentious relationship. But those umbrella terms exist for a reason, so it’s been a good challenge to ask myself, “What’s my problem with that label?”

It’s become something you can define your work in opposition to.

Yes, it’s affirming. No matter what the images look like, the political nature of the body is always my centring principle. And the experience of being a mom has definitely enforced the possibility of ecstasy and trauma living in the same place and flashing onto a body for a second. That’s the world of the paintings to me.

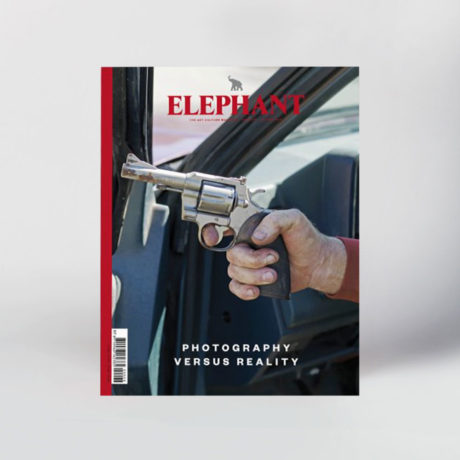

This feature originally appeared in issue 28

BUY NOW