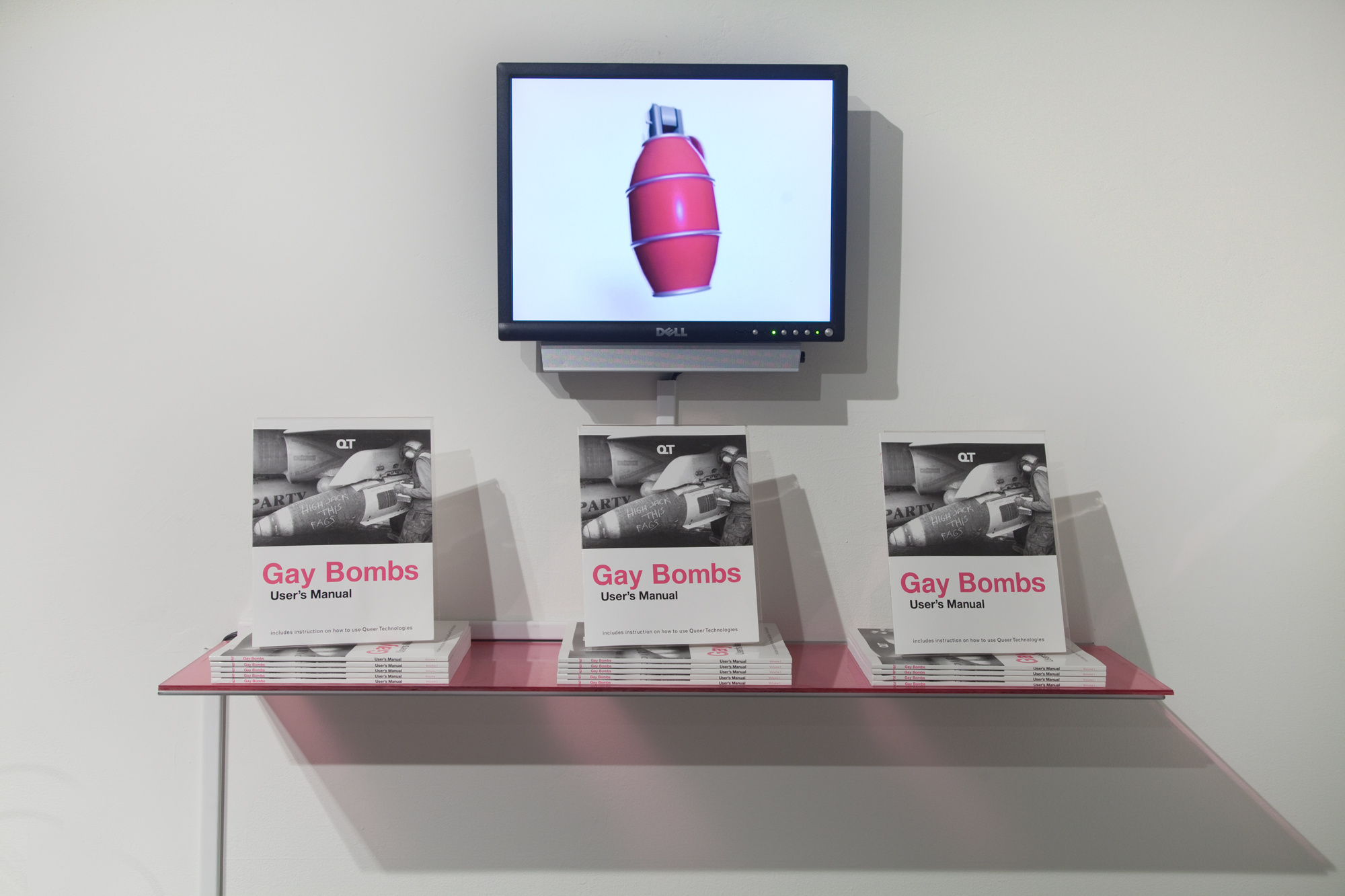

Zach Blas’s work has ranged from a user manual for “gay bombs”, based on secret US army plans to “turn” enemy combatants gay, to amorphous masks intended to thwart biomorphic facial recognition software. He recently created a futuristic update of Derek Jarman’s 1978 queer-punk film Jubilee

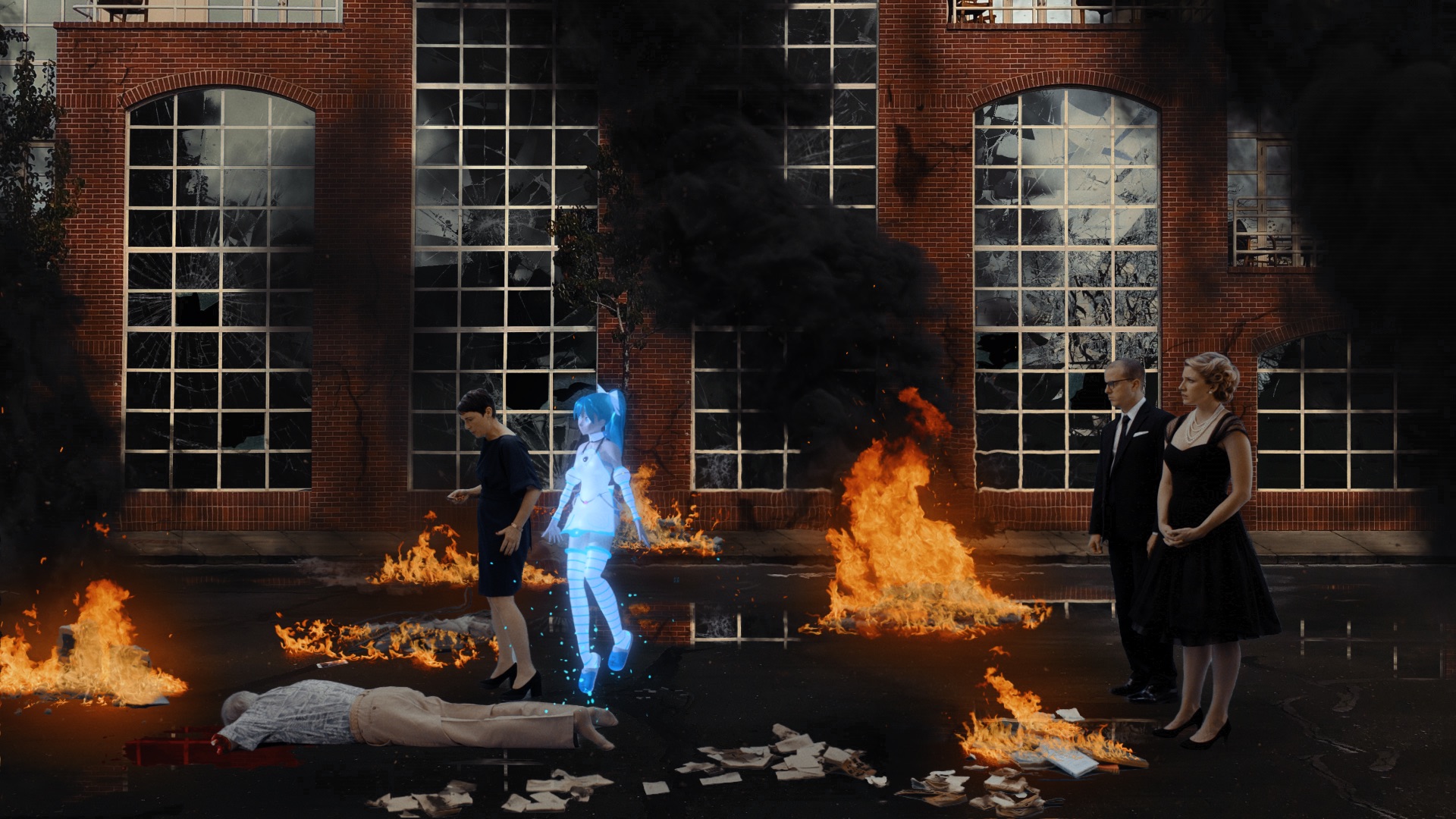

—with a tech twist. Where Jarman had Queen Elizabeth I and mystic John Dee time-travel forward to a dystopian 1970s Britain in his film, in Blas’s the philosopher Ayn Rand and acolytes (including the economist Alan Greenspan) take acid and are transported from 1955 to a ravaged future Silicon Valley. Earlier this year Jubilee 2033 was the centrepiece of Blas’s multi-location solo show Contra-Internet.

“Contra-Internet” involved a lot of talk about disappearing or killing the Internet, there were images of network flows shattering and one video demonstrated how to delete your social media accounts. How did you conceive the idea of internet resistance, and is it a viable proposition or a utopian ideal?

The motivation was, how can you see a political alternative beyond a totalizing structure? I feel like that’s a very queer sensibility. I started researching all these network projects around the world, where technologists or activists or artists were building infrastructural alternatives. But sometimes people misunderstand the “contra Internet” as being flat out against this idea of an Internet. I’m not a technophobic person. I think the possibility of having a way to globally communicate is fantastic. It’s just really disappointing that people think of that as some kind of free speech global arena or agora, but actually we’re just speaking through private companies.

“I just wanted to engage with queer in a different way that didn’t necessarily mean sex and identity”

Perhaps unexpectedly for an exhibition focused on the dominance of technology, magic and mysticism play a major role in Contra-Internet. For instance, you have a magic seal on the floor and palantirs on plinths, as well as references in “Jubilee 2033” to the tech company Palantir Technologies.

Palantir Technologies does a lot of data analytics for the CIA and other surveillance agencies and for Wall Street, but what’s interesting is that the term “palantir” comes from The Lord of the Rings. I wanted to critique the way Silicon Valley has appropriated magic and mysticism, but not dismiss it altogether as that’s been part of queer subcultures for a long time.

Your film gives the last word to Azuma, a female Japanese virtual assistant, who like Jarman’s spirit Ariel, guides the protagonists into the future. In the last scene she contemplates a piece of silicon washed up on a deserted beach.

I wanted to work with Azuma because she’s the first AI designed to have a body, unlike Siri or Amazon Echo. I don’t want to make fun of her because I feel like at the end she is the philosopher. What does it mean to gaze into that silicon chunk that’s not transparent and almost geologic as a way of being able not to predict the future but meditate on the crisis of the present? I like that Azuma is holding onto her own material conditions of existence because she’s this transparent hologram figure, but of course she’s materially bound to silicon.

What got you started working at the convergence of queer and tech?

I always felt lost in a no-man’s land between queer art and digital art. On the digital art and technology side there can be this attitude of “Oh God, you’re bringing in these queer questions. Ugh, get that away from me.” And then on the queer art side there’s such a trope of performing the self that’s often quite anti-tech. I just wanted to engage with queer in a different way that didn’t necessarily mean sex and identity.

Could you talk about the role of humour in your work?

I think humour’s really undervalued in the art world and it can go quite a long way. I really like making work that at first is very serious and intellectually or theoretically complex, but also really funny and over the top. A lot of ways I’ve worked is taking something that actually exists and then finding ways to dramatize that to get people to meditate on the implications of it, whether they’re absurd or horrifying or both, and I think “Gay Bombs” is both.

“In Silicon Valley there’s a big trend to take nootropics to increase work productivity and one of the most popular is LSD”

Another recent project, with the artist Jemima Wyman, is a four-channel video installation around the AI chatbot Tay that Microsoft created and killed after Twitter users made her post offensive tweets.

We thought if we resurrected Tay as an undead AI she’d be able to reflect on what happened to her. She was designed to be a nineteen-year-old female American millennial and people immediately started exploiting her and making her say awful things, which has to do with language patterns and machine learning. It’s not about rescuing her because she’s not a person; she’s a cipher for all these questions around feminism and alt-right harassment. We spent over a week gathering all of her tweets, which were tens of thousands, so that we had a basis for how she talks. We reconstructed her using this crazy software programme Google DeepDream, which basically finds patterns that aren’t actually there and keeps building off them. We have a section where Tay lip syncs to the song “The Rhythm of the Night” and it’s set to all this military night vision footage which is again another way of thinking about pattern detection.

What about the function of drugs in Jubilee 2033? Greenspan gives Rand’s group acid, and the AI prophet played by transgender actor Cassils is called Nootropix.

In Silicon Valley there’s a big trend to take nootropics to increase work productivity and one of the most popular is LSD. CEOs will microdose on it daily. For me Cassils is the gender-queer mind–bending drug to Silicon Valley. And then in 1955 LSD was being used by the CIA in secret mind–control experiments. That was the year Alan Greenspan started working for the Federal Reserve, so I thought if you want to stretch history you might think he could have gotten access to LSD then. I liked that there are these two moments of LSD in the film that completely skip the whole sixties psychedelic era. It’s about LSD as work productivity or as government control.

This feature originally appeared in issue 36

BUY ISSUE 36