“Trust!” Niamh O’Malley and Ciarán Murphy quips on the exact same second at GRIMM gallery’s New York space last month. Their synched reaction is in response to my question about opening solo exhibitions at the Tribeca Gallery at the same time. Confidence in each others’ work has been a shared sentiment between painter Murphy, who invited his sculptor colleague into the two-story gallery, as well as for O’Malley to accept the gesture.

The two artists are not only both from Ireland, but they were born in the same coastal region of Mayo, on the country’s west, three years apart in the mid-1970s. Murphy, however, lives today in Callan, a town in the south of Dublin where O’Malley resides. The two had indeed never met before opening their concurrent shows on the other side of the pond or not even Zoom’ed. The joint show idea came to Murphy “spontaneously like all great ideas,” he laughs. “I knew that too many paintings can be problematic, but contrasting materials can create new conversations.”

For O’Malley, there is an inherent comfort in being paired with an artist working in a different medium: “Comparisons don’t become cliches with different materials. They become about sensibilities in that case.” Between his own hallucinatory paintings of precarious human experiences and her physically rigid yet emotionally fleeting sculptures, Murphy finds a similar thread, too. “We both ask to look slowly,” he says. “We similarly have that semi-transparence, both in our visual languages and material choices—there is something you can see through, something opaque.” Attention is indeed an urge O’Malley tries to alchemize in her metal, wood, and glass sculptures as something almost malleable. “Capturing attention is a fleeting feeling,” she explains. “Care is something I think about—support, poise, and being held and holding.” She thinks they both have practices “grounded in small gestures and quiet moments holding something together, and we both edit out spare moments: being present in a chaotic time.”

Murphy’s hazy paintings in various scales capture lingering instances as much as the ways they are remembered—he depicts an absorbing moment as inseparable from its memory. Figures are drenched in their emotions, which the painter leaves vague, both through their aloof expressions and his powdery palette. Gelatinous film stills and worn-out photographs can be equally attributed to his rendition of an experience. Nature lingers as an afterthought, as well as the burdens of urban life. Being present—even excessively—in a moment is also an intrigue for O’Malley. The unending rituals of everyday life and the warped relationships they build between us and textures and forms are echoed in her mysterious objects. After representing Ireland in the last Venice Biennale, she presents a more intimate installation of her sculptures at GRIMM’s basement space where feelings of immersion and estrangement somehow mingle. Familiarity of shapes is challenged by O’Malley’s forging them as allusive invitations.

Being from Ireland is not an overlap the artists necessarily see as a connection in their works. “I am interested in language and living in a world where we’re completely bombarded with images, which is a global phenomenon—that is the context I think of myself in rather than a geographical one,” says Murphy. He believes culture does create signifiers in an artist’s work, “but I simply think we’re all in some sense having to negotiate our subjectivity, which is a universal theme. O’Malley agrees and also thinks that traces of a place in an artist’s work are “for other people to see because it is very hard to see when you are within it.” As an artist working in natural materials, she thinks geography, however dictates the character of her materials: “I am interested in the geography of the physical places you are from and how they shape your sensibilities; they in a way form what appeals to you.” Growing up in a mountainous area, she assumes, has affected “how I use materials, or how I compose things, as well as my body’s relationship to the landscape I grew up in.”

Osman: This may be an odd one to start with, but a lingering sense of anxiety is a thread between your work, Ciarán. There is a feeling of suspended tension that is not apparent on the surface.

Ciarán: I like the observation of anxiety. It’s not something that I usually see, but I really like that kind of observation. The effect of anxiety is something people try to describe because it is not a feeling we easily have a word. Fear has an object to it, whereas anxiety is object-less. There is something about things being hanging in my work, or there is a sign of fragility. The painting windworld, for example, shows the arms stuck in the air, or they might be falling off. There is a paradox in the way the arms are like marble, very heavy, but there is weightlessness to them with a tension of push-and-pull. I agree things look unsettled and anxious. Speaking of tension, I thought about the word “whirlwind” when titling the work, but I wanted to switch the words and settled on “windworld.”

Osman: How do you source your images?

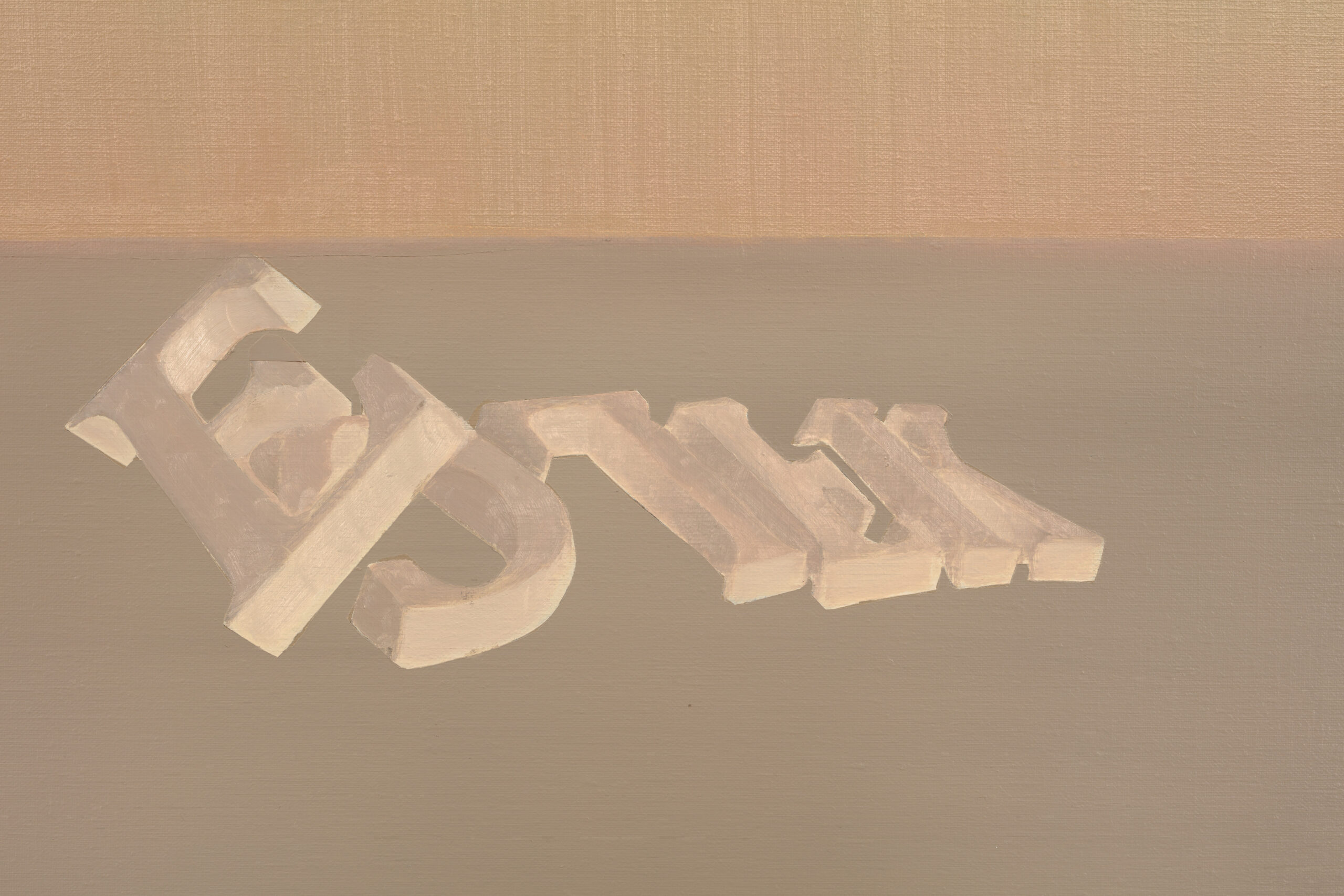

Ciarán: I take my own images and work from there or sometimes I look into the internet. I occasionally look into three-dimensional things in front of me, like the piled letters in the painting melt. They are from actual wooden letters that I photographed—I see them as props. Photographing them helped me get some architectural angle. The painting of the bird holding the hand, flutter, is from an image of my wife holding a not real but a cut-out image of a bird. I like mixing a so-called real image source with a representation of the real.

Osman: Do the letters actually read a word?

Ciarán: People ask that but I just paint them as kind of new objects in a way. There is a sense of apprehending the word from a moving vantage point, like from a train or from a car. The letters are a part of the landscape—they are sharp and rise from behind.

Osman: In contrast to what I just said about the anxious aura, your colour palette carries uplifting tones with powdery shades of bright colours.

Ciarán: It is a way of trying to get the right balance. For example, those three separate paintings of a face being covered by the figure’s hands have white tones that come from my studies of foggy landscapes. The purples are from photographing a white wall which had purple photographs being projected. I like it when a colour in one work is translated to depict another totally unrelated thing. This creates chance encounters between experiences and narratives. I surprise myself, too, for sure when elements of chance come out. In moon day, the figure is pushing against the wall, but they are caught off-guard on the foreground, and the shadow suggests actual weight.

Osman: I am catching a few repeating elements in your work Ciarán, and maybe “obsessive” is the right word.

Ciarán: Obsession is a good word. I used to make absolutely terrible paintings, repeating something, but I still like that echo. I am still curious if I will paint something again. I stop when I start plagiarizing myself. If something works, you naturally want to do it again. You feel like you’re agreeing with something, and there is a temptation to keep doing it.

Osman: Niamh, your approach to materials is varied but also determined in a way: glass, stone, and wood. Maybe this condensed roster of materiality has something to do with that.

Niamh: Yes, and that also is about practicality. I now know where I can get certain materials around my studio, and this even ties to an ethical point of view because I won’t be carting things from somewhere else. Using right materials happens to be something which is inevitably close to my habitat. I do use more materials than a painter but it is still quite a small repertoire of materials. As you said, they are wood, glass, stone, and it takes me a while to add more materials.

Osman: Nature is a subject in both of your works but in distant ways, maybe more directly in Ciarán’s depictions and rather alluded in Niamh’s sculptures.

Ciarán: A lot of artists have that one painting of a primal scene, which they always look back at for ideas. For me, it is a painting I did of a snow hare in 2006. The image is based on a taxidermy in the Natural History Museum, where the stuffed animal sits inside a box with fake snow. It was an interesting thing to paint because I had all the elements of light, colour, and texture, but they were also not quite there because the whole inspiration was from symbolic taxidermy. There was a tension in the process because I was painting an idea of nature; the subject was entirely dead, of course, but there was still something about presence.

Osman: Animals, in general, hold that mystery when you paint them because their emotions are impossible to fully grasp on our end.

Ciarán: Yes, they fully hold an enigma because they don’t speak, which is part of the attraction. They are never fully disclosed or interested in being fully captured.

Niamh: I made a film in a marble quarry which led me to learn a bit about their process. And then, one night, I was standing on the street in Dublin in the rain, and there was a really beautiful limestone paving in front of where I was sheltering. This was in the doorway of a fast food place. The paving was full of fossils, and I recognized it as limestone. I just started to think about that kind of support structure of the cityscape as well as our effort to harness a support structure that works for us, the people inhabiting the cities. This structure is still visible somehow; I thought of the idea of reproducing and rebranding a similar structure inside a gallery. If you look closely at the drain sculpture, it is full of fossils—it is compressed limestone seabed. Cutting this massive piece from under the water and plugging it here at the gallery reminds its porousness and the possibility of water still pouring through it. I didn’t want to make it in steel or any other material. It needed the water’s flowing feeling. I previously made a similar work which was almost like a doormat that people had to wipe their feet off while entering the gallery.

Osman: Niamh, Parenthesis sculpture has an alarming aura, almost as if it was a tool available for a potential hazard, waiting to be reached for survival.

Niamh: Somebody also said they look like a type of farming tool but they are parenthesis, physical brackets. They are about language and being somewhere in between; they can be hooks or handles for language or architecture. They are framing and holding a space. I like them sitting within all of those structures. In terms of material, they are polished wood, just like the tubes in Lightbox sculpture, which replicate light tubes in their exact scale and shape. You can see them as candelabras, too. I have been photographing empty light boxes and billboards for years for no particular reason. That has evolved into this piece where I thought about just the idea of display and the materiality of it. I was curious about what holds the energy to push out some information, and I wanted to make the box itself reflective as an object where you can see yourself.

Osman: Lightbox has a very sleek presence, carrying a clinical-level clean idea of a vitrine.

Niamh: I like the idea of a mirror, which is a material I worked with for the first time. The work is very open about what it is made out of—it is not trying to kid anyone.

Osman: The fluorescent tubes are wood, and the wires are steel. And in Vertical, clear, lean, the leaves are glass. You like to replicate objects associated with specific materials in completely different ones.

Niamh: Wood as a material has latent energy because it can be burnt; it has an energy source in itself. I see this as a translation of something that emits light to something that holds light. Limestone has been massively compressed—imagine huge amounts of waste to form it into stone. The drain sculpture, in that way, also holds that latent energy, and of course, glass, coming from sand and turning to liquid, has a similar trajectory. I like using these materials that still hold their histories in the new forms they are transformed into.

Osman: The two shelf sculptures with glass shards also have a hint of risk with their sharp ends, reminding another aspect of the material beyond beauty.

Niamh: Yeah, they deliberately look almost broken.

Osman: And, their silhouettes are in landscape form, which perhaps ties to the paintings upstairs.

Niamh: I am sure Ciarán has this feeling too: in a show, I sometimes need what I would call a horizon line to cut through the works. The whole show has a composition of sorts, held together through a composition line.

Ciarán: Yeah for sure. And this makes me think again about making images in a world full of images. I am thinking about veiling in a painting. How do you both present but a little bit conceal too, let’s say, a face. Images these days don’t have that—the images of disaster or violence are all revealed. The result is perhaps feeling like rabbits in the headlight with images constantly coming and feeling frozen against them. Allowing subjectivity to emerge to have a little bit of breathing space is needed in the work.

Osman: Fogginess is something you definitely dabble with, Ciarán, perhaps also to hint at how memory works too.

Niamh: Trying to pin something down or grasp it is how I would think about what it means to make something. Think of the idea of physically reaching to something hoping it will solve an issue.

Osman: Speaking of reaching out to something, Niamh, how does it feel to bring your Venice Biennial works here in a new context?

Niamh: This is the third time I am showing them, and it’s just really nice to rehang them in a different relationship with other objects. When you are making new work, full stop is sort of an arbitrary understanding. Even when there is a deadline for a show and you bring the finished work in, it is always moving on, perhaps coming from the extension of a previous work—continuity is always there. Every time you hang a show, it is a different relationship between you and the room. I like seeing the parenthesis sculptures enter different architectures, for example. I’ve been carrying my parentheses to different shows, and here, placing them on two cornering walls with a door in between has a new meaning.

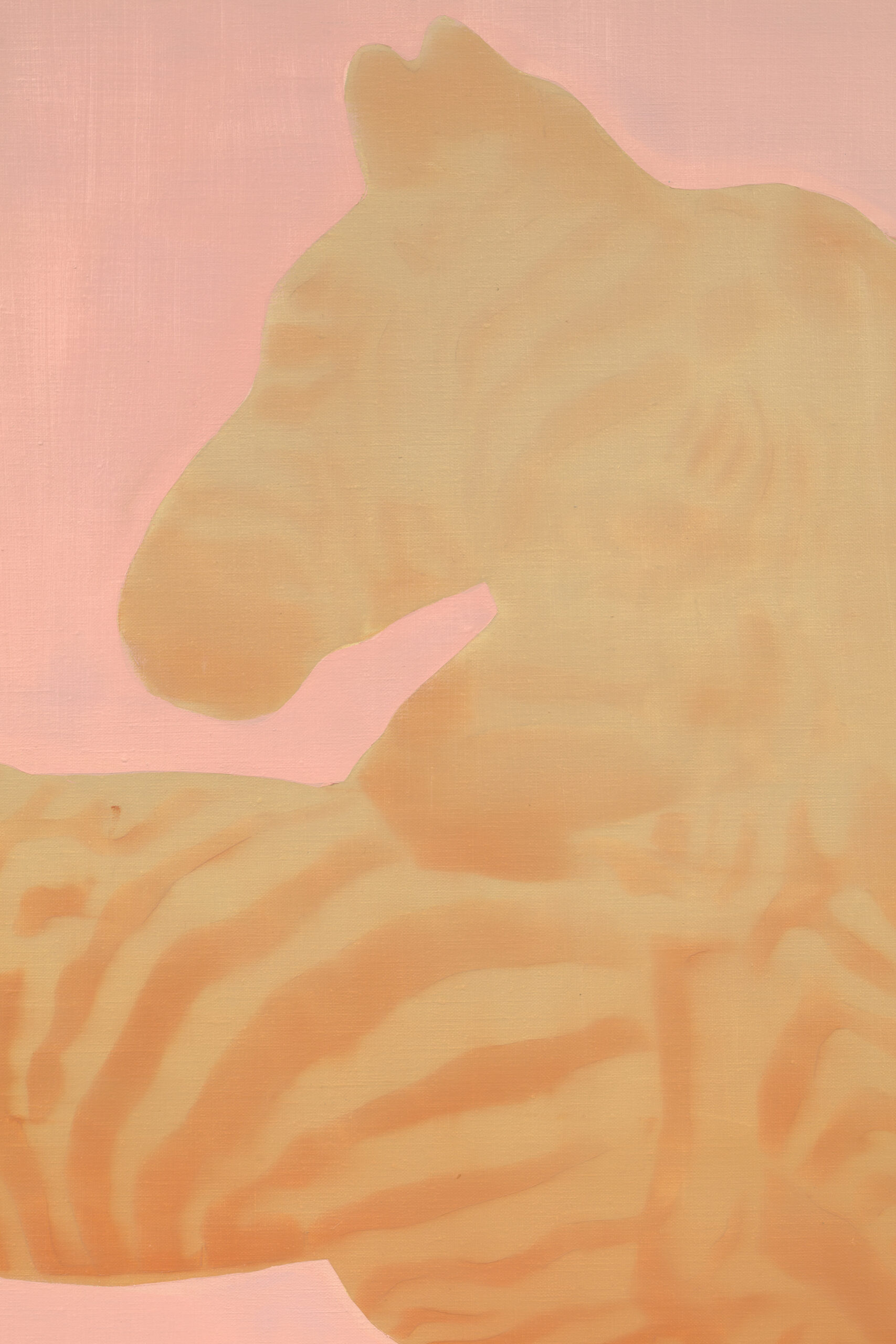

Osman: A parenthesis is interesting because it is a break, a pause, but not an end—it is not a period. Movement is an invitation in Niamh’s sculptures with their both kinetic and static energies, but it is also depicted in Ciarán’s paintings, especially in the zebra painting, herd. Ciarán: Funny you say that because my show’s title, still, weight, thing, also refers to “still waiting” with that decidability. There is that elemental aspect of anticipation and openness to more to come.

Written by Osman Can Yerebakan