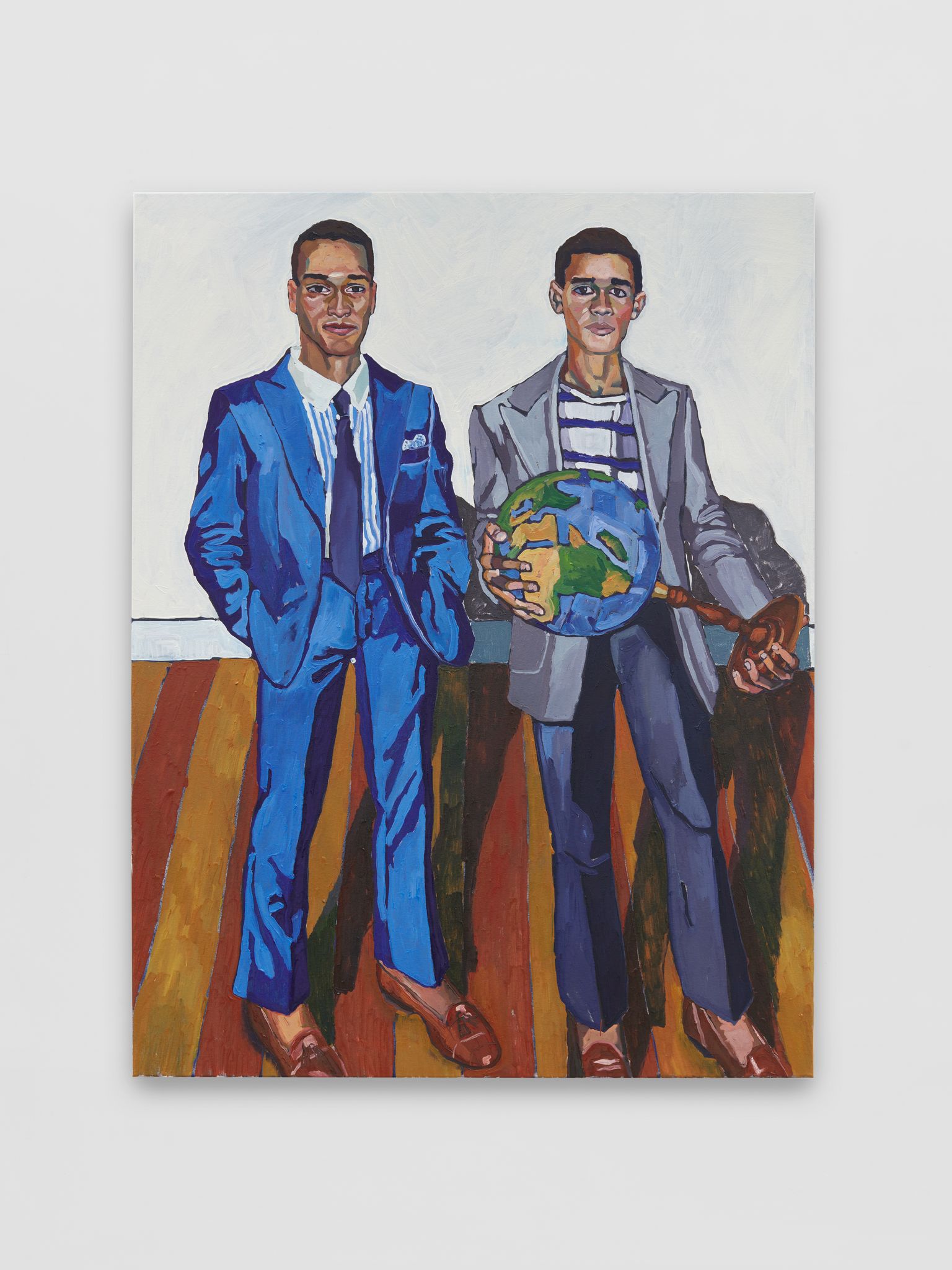

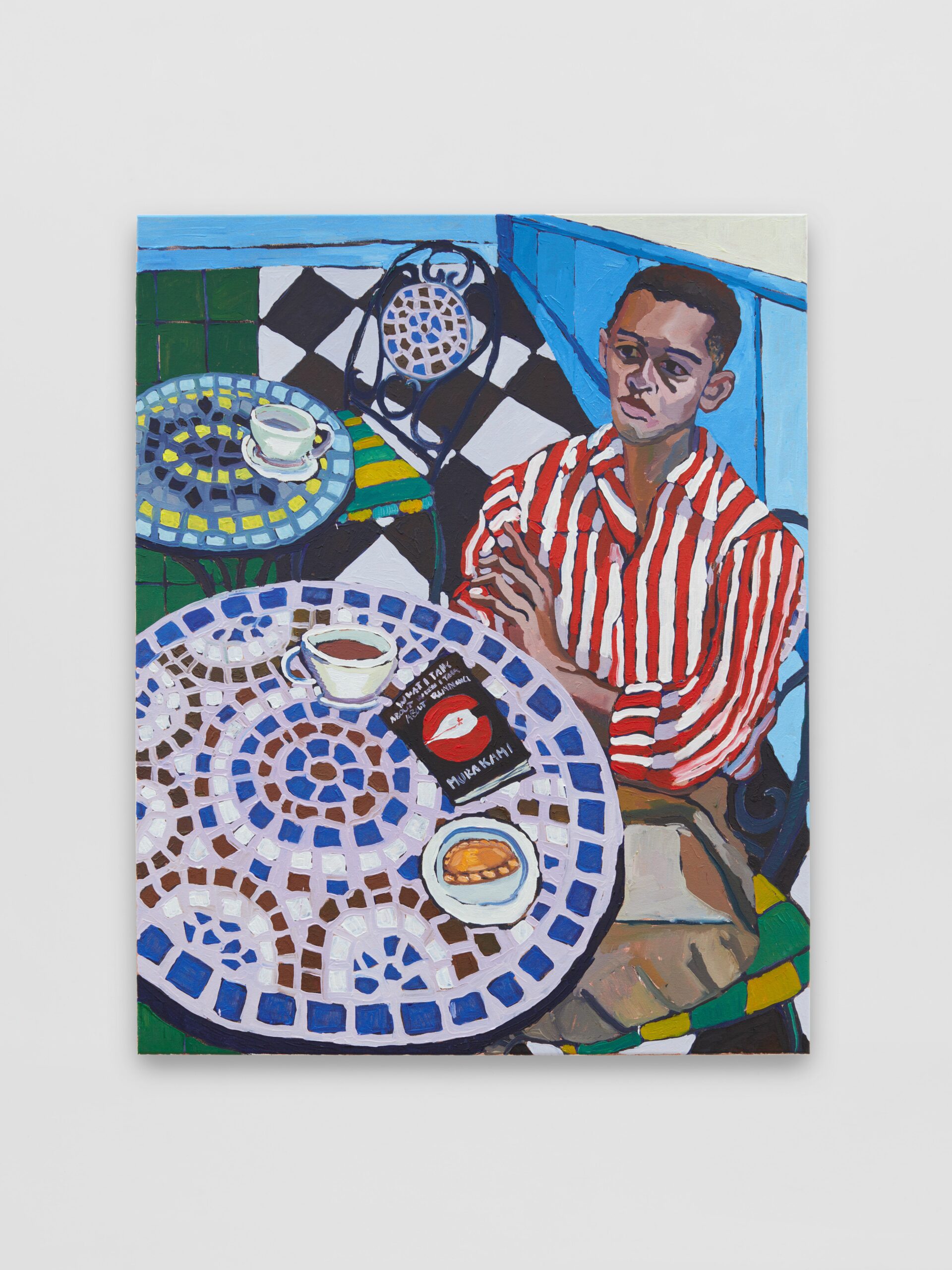

During an early summer residency spent at our north London studio space, Nicolas Coleman produced a series of paintings that document his time in the city. These works served to illustrate his latest explorations into the psychology of geography and travel; how the nature of a person’s surroundings can influence their emotions, sensations and ideas of who they are.

His painting process is informal and intuitive, contributing to subtly energised atmospheres and suggestions of narrative. Detail is worked into every surface, object and character, levelling the demand for attention of these elements, and encouraging the viewer to inspect with intrigue the background and foreground, as equal components.

In a remote discussion from Barcelona with Daniel Mackenzie, Nicolas reveals a side to his work not often explored in detail, and that runs in contrast to the largely calm and convivial nature of the scenarios he paints: as human beings, our emotional complexities conspire with the spaces we exist in and travel through, producing unpredictable and contrasting personal experiences that jar with the external environment. We are found wondering to what extent, even in the most idyllic of places, we can truly let go of who we are, and what we bring with us.

Daniel Mackenzie: You’ve just spent a month in London producing some new work. I’m keen to know how your time there was and how you might have been influenced by the city.

Nicolas Coleman: It’s a really cool place, I really loved it. I was there for three days in 2018 and just did all of the tourist things, so I didn’t really get a sense of what it would be like to live there. On the residency I eventually found my routine and the places I liked to go, and I really felt like I could ease into the city. I assumed it was going to be more like New York but it’s far less chaotic and I really loved how unique all the different areas are, like where I was living versus where the studio was.

DM: I suspect there’s a huge and complicated crossover between your experience in the context of being first and foremost a person, but also an artist. How much foresight and planning went into the trip?

NC: Well I didn’t really have much of a plan for what I was going to paint, just a couple of ideas so I had something to start on when I got there. I tend to paint in a very autobiographical way, a reflection of where I am, what I’m doing, what I’m noticing, but it wasn’t obvious to me what that would mean in London. I’ve done paintings before based on visits to other places; one on Morocco and one on Venice. Those places have such a distinct visual landscape with these obvious architectural or environmental symbols, but London is a very cosmopolitan city and I didn’t know exactly what that would look like, which was exciting – it caused me to find the things that stuck out to me. In a city that can feel so international I think it says a lot, what stands out to a person, and I was figuring out what caught my attention. In the studio I thought about what I remembered from the last day – being in the park, in a cafe, things like that. And that was what my time in London was like, made up of these places that are not necessarily symbolic of London, but they were symbolic of my time there.

DM: I like the idea that you paint autobiographically, but it’s also like a kind of travelogue. As an artist you respond to places intimately and personally, and the viewers of your work get to know you as an artist and a person based on how you curate, and communicate, your experience of travel. It’s always interesting to learn about an outsider’s perspective of somewhere as diverse and cosmopolitan, but familiar to us, as London. I’m wondering how much you were able to feel the more extreme contrasts and diversity of the city, and how you were responding to the characteristics of the environment.

NC: I feel like I got to see a lot of different parts of the city through the circle of people I was spending time with. I visited a few friends where they live, one of them lived near Angel station and I like that area. I went to a dinner party in a residential area actually further in West London than where I was staying in Maida Vale. When I was thinking about what to paint I was focusing on the times when I was by myself, an individual in a place that is not necessarily familiar to them. I don’t know if that was intentional. Probably because I paint self portraits it’s a little bit easier for me to do that, but I guess that’s what you’re getting at, the idea of seeing the place through my eyes, but also me looking at myself existing in a new place.

I’ve chosen painting to explore that, but it’s really part of a broader form of introspection. The idea of taking yourself and putting yourself in a new context changes how you think about yourself. Obviously the park that I painted was not visually identical to what Regents Park looks like as I was doing it more or less from memory. In a way it could be anywhere, but when I’m painting it’s about what from my time somewhere stays with me when I get to the studio, the scenes and people, whatever I could remember.

DM: So when you’re painting it’s a collaboration with your memory of the place, the place itself, how you remember feeling at that time, but then also to an extent how you’re feeling in the studio. Now that I know this about your paintings I can look at the work and see these different layers of depth, like you’re painting at different times and different mindsets all at once.

NC: It’s somewhat instinctual and I paint quickly in reaction to whatever I’m doing, usually the day after whatever I’m painting happened. It never turns out exactly how I would expect though, and yes it’s a negotiation between my immediate memory and my reflection while I’m doing the painting.

DM: Morocco is full of overwhelming visual stimulation – the fabrics and patterns, that amazing blue, tiny frantic streets and expansive landscapes. No wonder you felt inspired there. I suppose less visual assistance might create the conditions to lead more with introspection in other places.

NC: London was kind of a perfect place for that because yes, Morocco just has so much beautiful visual stuff that I can lean on to make an interesting painting. If I’m painting a complicated interior scene with really beautiful patterns in everything, it’s a little bit easier for it to be a compelling picture than the general idea of being in a park, which requires a little bit more thought to avoid it being boring or generic. That was something that was really cool about London, something I wasn’t so sure how it was going to work out but ended up being really interesting.

DM: Something I’ve noticed about your work and also the way that your work is generally written about is that it all seems largely upbeat – words like ‘delight’ come up quite a lot. I’m keen to know just how accurate that is. Perhaps aside from the Morocco series, where you called into question the ethics and culture of tourism, there’s this almost utopian and idealist viewpoint on societies and people, and maybe even to some extent your experience of being in the places that you’re in. I suspect it isn’t as simple as this.

NC: I think the short of it is no, it’s not entirely meant to be idealistic, especially not emotionally. I was happy to speak on this regarding the Morocco series because a lot of the reaction seemed to be that the paintings were delightful in a way, whatever that means for people. But there is a distinction between the way that I paint and then what I’m painting. There’s a lot of energy and colour, and the way that I apply the paint and do the figures, there’s something that’s sort of utopian about that in a way – I really enjoy a sort of maximalist approach to the brushstrokes and the saturation of the colour. It seems like there’s something almost naive about it. It’s an outsider’s perspective on a place and a passionate curiosity. Then I think that if you look at the content of a lot of the paintings, it’s not like I’m painting myself smiling.

DM: Well despite all of these delightful aspects of a painting, and the beauty and atmosphere where you are located, why would you have to be?

NC: Yeah, a lot of it is actually about the isolation of being in a new place. There’s a bit of a contrast there where I can do a painting that is really lively and bright and colourful and visually rich, there’s a delightful application of paint, but the underlying content or narrative is not necessarily utopian or idealised. Sometimes it’s directly self-critical or just critical of the subject that I’m portraying. A lot of the time it’s a sort of subdued expression that I’m trying to get across.

DM: You could say the same for other characters that appear in the paintings. They are often engaged in leisure, the kind of activities that those in a well functioning society would be able to enjoy. There are people in bars, on boats, eating in some atmospheric setting and things like this, but there’s this tension, like they aren’t really invested in the enjoyment of the activity. This links back to the personal travelogue and how you view yourself as an individual in a different place, how you analyse yourself in a different way. Often when I’m alone in amazing and beautiful places – which I do really enjoy – I’ve struggled to let go of all of the seemingly eternal personal battles you have with your own psychology and emotions. All the sights and sounds aren’t enough to help me disengage from all the difficult things that are going on internally. I can see myself in your paintings, sitting at that bar, with that glass of wine, in that peaceful place by the river, yet there is still something wrong.

NC: That’s really true to how I feel about it. Part of the idea and part of why I like doing self portraits so much is that it’s not like I’m painting a figure to stand in like a mannequin. Painting a park scene without me in it, it very much becomes like I’m just sort of passively experiencing this objectively pleasant environment. When you’re painting yourself in, when you’re painting a memory of something that you did, you have to approach it like it’s your entire self – not just this momentary photograph of you in this interesting place. It becomes a much more psychologically complicated subject, especially with the backdrop of what you describe as these typically leisurely activities. That’s a subject that has always been so important in painting; the Impressionists particularly painted so many scenes with people, you know, just bathing in rivers.

DM: Yes, always by a river those people…

NC: Yeah! That’s been an obsession with painters in the last 200 years, painting modern life through these leisurely activities where you’re showing the lighter side of society, and that really interests me. I don’t want to paint myself doing taxes or something like that, I activities that people can connect with, a kind of symbol of freedom, in a way where it’s still me, feeling a certain way. These are the painters that have been most impactful for me. I think about the early modernist era, like Matisse and so on, and these paintings of Arcadia, or their version of Arcadia, with all these usually nude figures in this beautiful natural environment, this Garden of Eden type place. They were painting them in a purely conceptual way where the figures weren’t even necessarily real people, they didn’t have any identifying features, they were just in an idealised form. Using that idea but doing it as a self-portrait forces you to do the complete opposite of that, where it’s completely about the individual. When you’re really putting yourself into some context, it’s a hyper specific portrait of a person.

DM: Despite this hyper-specificity then it’s even more remarkable just how easy it is to replace the figure in the painting with oneself. It’s something to do with the richness of the environments and the ambiguous emotional tones, I’d say, those are points of access. Even with some of these unidentified places there’s something about how clearly communicated the atmosphere is which makes them so easy to to approach. You’ve said that representation is not your goal. I wanted to ask if there is a central goal with your work and what that might be – to communicate some personal ideology or more universal human ideology?

NC: I probably do have a main goal but I think that it’s very evolving. I would say that the consistent thing relates to a personal ideology, I think you’re quite correct with that. There’s this idea that I found through betraying myself in cultural environments that are not necessarily my own. I think that it speaks to a sense of what I feel is a universality of these experiences that can’t be defined necessarily by the person or the place; it’s a constantly evolving interaction between the two. To be more specific it’s the idea of me in London, me in Morocco, me in Venice – it’s still me and when I’m there the environment becomes mine in a way. I’m still a stranger in the place, a visitor, but it’s a way of examining how we define what a person’s place is.

DM: When you’re talking about the idea of place, I read that as belonging, or the right that somebody might have to feel connected to or familiar with a place. It doesn’t come across as a political statement about nationality, borders or displacement though, it seems more about you as a human being, and extending out from that, the human experience generalised and outside of contexts such as those.

NC: I don’t think of it as political; I think about it in a more broad sense. That’s part of what I mean when I say representation isn’t the goal – I don’t care if a painting doesn’t look like me, it’s still as much of a self portrait as one that looks more naturalistic. But the way you said you can imagine it being you, that’s what the goal is. I’m aiming for a universality of what the experiences are. That is really important to me and part of why I like the idea of painting my travels.

DM: I think the intention is clear regardless of these complications.

NC: One of the other things about the series that I did before coming to London, is that those paintings were not so much location dependent – I used props in place of the location. So instead of a really defined setting I would include books, food, furniture, or whatever, evoking ideas of who should be reading this or who should be using those, who should be eating this. That sort of stood in for the location. I could paint myself sitting at a table and what I put on the table would change so much about the immediate interpretation of who this person is, in the same way that a place does. That’s something that painting is really successful at being able to capture.

DM: In some sense, there’s something very freeing about knowing that you’re seen as a stranger in a place, but at the same time there is this feeling of loneliness. And when you’re surrounded by beauty and this exciting energy, that feeling of loneliness is uniquely complicated. You bring so much of yourself and whatever it is that you’re going through with you.

NC: I suspect that this is something that most people can feel. I don’t think there’s anyone who has only had good emotions in beautiful places or only had bad emotions and bad places.

DM: Oh sure, I think that would be quite an oversimplification of how the human mind actually works.

NC: Right, there is a way to do art intersecting with travel in a way that’s really celebratory. It’s entirely possible that I can make a painting with just a few small tweaks that would change it from being just me taking in the beauty of a new place – there are people who do that really well. It’s not at all a criticism of a utopian vision of the world through art – there’s something really useful about that as well. I felt it was kind of unexplored, this sort of more complicated, introspective or psychological idea that we want ourselves to be different in a new place, or how we think that we should be perceived differently in a new place. When you’re the one who is contextualising yourself, it’s by knowing how you were feeling before. I knew how I was before I was in London, I knew how I was probably going to feel or what I was going to be concerned with when I left London. The location is the transitory part, I’m not making a temporary version of myself. It’s the same person, the same person in all these paintings. We have these really long term emotional arcs in our lives that stretch for years and years, and during that period you end up in so many new places.

DM: It’s the journey within the journey right?

NC: Yes. One of the reasons I’ve become infatuated with this theme of travel in my work is that the more we go to new places, the more infinitely complicated the lens becomes through which we chronicle our own experiences and emotions.

Words by Daniel Mackenzie

*Nicolas Coleman is currently exhibited with PM/AM at 37 Eastcastle Street in Central London. The show closes on 19th September.