Selfies are a cliché. Talking about selfies is a cliché. But perhaps their social meaning hasn’t been fully explored yet. Maybe we reached ‘peak selfie’ a decade ago during the memorial service for Nelson Mandela in Johannesburg when Danish Prime Minister Helle Thorning-Schmidt took a picture of herself with President Barack Obama and British Prime Minister David Cameron. Three world leaders watching themselves being watched by millions of online followers and the media (there was much discussion about whether the chummy trio were disrespecting Mandela’s memory) bunching up, leaning back to get the right angle, showing off their very special relationship, grinning with high-definition relatability. The First Lady looked elsewhere, unincluded and unimpressed.

Of the nine paintings in Taína Cruz’s ‘HOUND’ (all works 2023) at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin, none are selfies, but five are portraits produced under social and artistic conditions that are utterly selfie-suffused. The fragmented narrative structure of the titular video implies some surrealistic, barely articulated inner turmoil: bugs turn into dogs with lolling tongues, women with rigid grins weep in fast food restaurants, a dance routine in which an athletic woman in sportswear steps in time with a mythological witch-like figure. The uneasy feeling the film evokes is, however, fixed in the paintings Time out Clone, Eyes on You, and Tyra in the Middle, which can be read as a contribution to and product of portraiture in the age of the selfie.

Describing Cruz like this is risky. It’s very close to being reductive and might diminish the works, making them sound like a gimmicky student project based on a social theme or a big provincial exhibition that has to appeal to as broad a public as possible. And it may also come at the price of ignoring the artist’s reflections on her family history and indigenous Puerto Rican folklore. The way out of this is to look at the implied cruelty in eerie portraits Time out Clone, Eyes on You, and the take on the visage of supermodel Tyra Banks in Tyra in the Middle, in the light of the three howling high-cheekboned elf-like creatures in Screech, as well as two works that don’t appear in this exhibition: Look’ere I picked this up on 125th (2023) from ‘Of Orchids and Wasps’ at the gallery (March-April 2023) and Ice Princesses of Harlem (2023), which viewers can see on the artist’s Instagram page. This, in turn, allows us to think about the relationship between selfies and the condition of portraiture since the 17th century. Artists back then had to navigate between competing demands: showing the viewer what the sitter really looked like for posterity, flattering them even when they weren’t worthy (also for posterity), and pleasing a patron – see, for example, Thomas Gainsborough’s letters to the Earl of Dartmouth in 1771. Seven decades later, in response to the invention of the daguerreotype, photography pioneer Henry Fox-Talbot emphasised how natural light used in photographic processes greatly increases the ‘truth and fidelity’ of the image that can be achieved in portraiture. In the last century or so, however, some artists – see Léger, Francis Bacon, Gerhard Richter, and many others – have questioned or even openly abandoned faithful representation as an artistic aim because photography does this so much better.Susan Sontag said we live in an ‘image-choked’ world; Jean Baudrillard argued, in a way that seems prophetic today, that the very relationship between the real and the imaginary has been fatally fractured. Indeed, in the opening decades of the 21st century, we are struggling with a disturbingly widespread social problem that started with photography but won’t end there. Large numbers of people exposed to the Internet can’t tell the difference between truth and lies, fantasy and reality. They are able, however, at the same time, to take and manipulate images of themselves and their surroundings – completely consumed by the demands of the present with little to no thought about posterity – and post them online for the world to see, chattering about how they do this and how it affects them and the society they live in.

These are the wider conditions under which Cruz is working. So while Time out Clone and Eyes on You opens up questions about whether it is worthwhile or even possible to show us what a human face looks like and what it tells us about their inner life. Tyra in the Middle is, however, thematically important for Cruz’s work because the person it represents – creator, executive producer, and best-known main host of the reality television series America’s Next Top Model (2003-18) Tyra Banks – has contributed much to a vital part of the dominant structure of feeling of our times: delight in spectacles of hollow venal nastiness. We now live in a world where everyone able to take a selfie is their own top model, subjecting themselves to the same unforgiving gaze that Tyra Banks so relished.

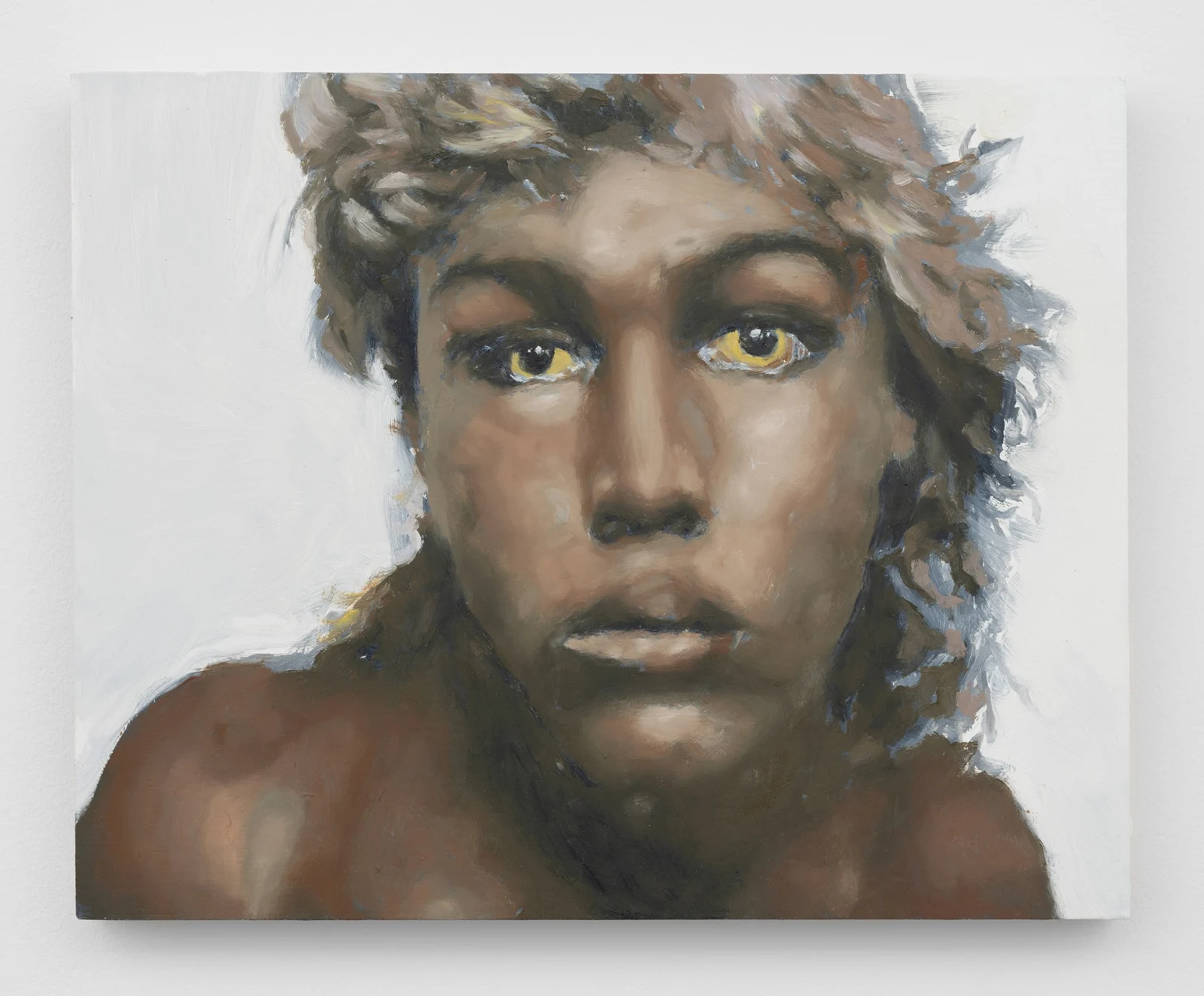

This is, of course, nothing new. America’s Next Top Model and the tenor of shows that it influenced is just an update on the theme of cruelty as magnificent entertainment, from ritual war hunts to human sacrifices to gladiatorial combat to public corporal and capital punishments. Even if Tyra Banks isn’t a torturer or executioner, and even if Taína Cruz took a photo of Banks to celebrate her personality and achievements, Banks represents how humiliation as recorded, endlessly repeatable fun has become socially sanctioned, embedded in cultural life. What we then see in Taína Cruz is, perhaps, the emotional conditions that Tyra Banks has done so much to influence, shaping the ghoulish anxieties of Look’ere I picked this up on 125th, Ice Princesses of Harlem, and in a slightly different form in Screech, and what may be their private, personal consequences as they appear Time out Clone and Eyes on You. Eyes on You and Time Out Clone are, indeed, portraits in the mode of self-reproach. One extreme of selfie-making is, of course, about creating a glorified fantasy image of yourself as you desire to be desired by others, whether the image is made to survey or assess your own face or body or for someone else to do that. These two works give us a taste of another pole. Both faces wear a paradoxical expression of highly expressive detachment: they gaze at the viewer with sickly yellow eyes – this is typical of Cruz – without the real or imagined identity of the sitter or viewer being clear. Perhaps they’re surveying themselves in a mirror, being caught miserably off-guard in a mugshot or in a graduation photo, trying to anticipate how this image will look in years to come. The result is emotional illegibility.

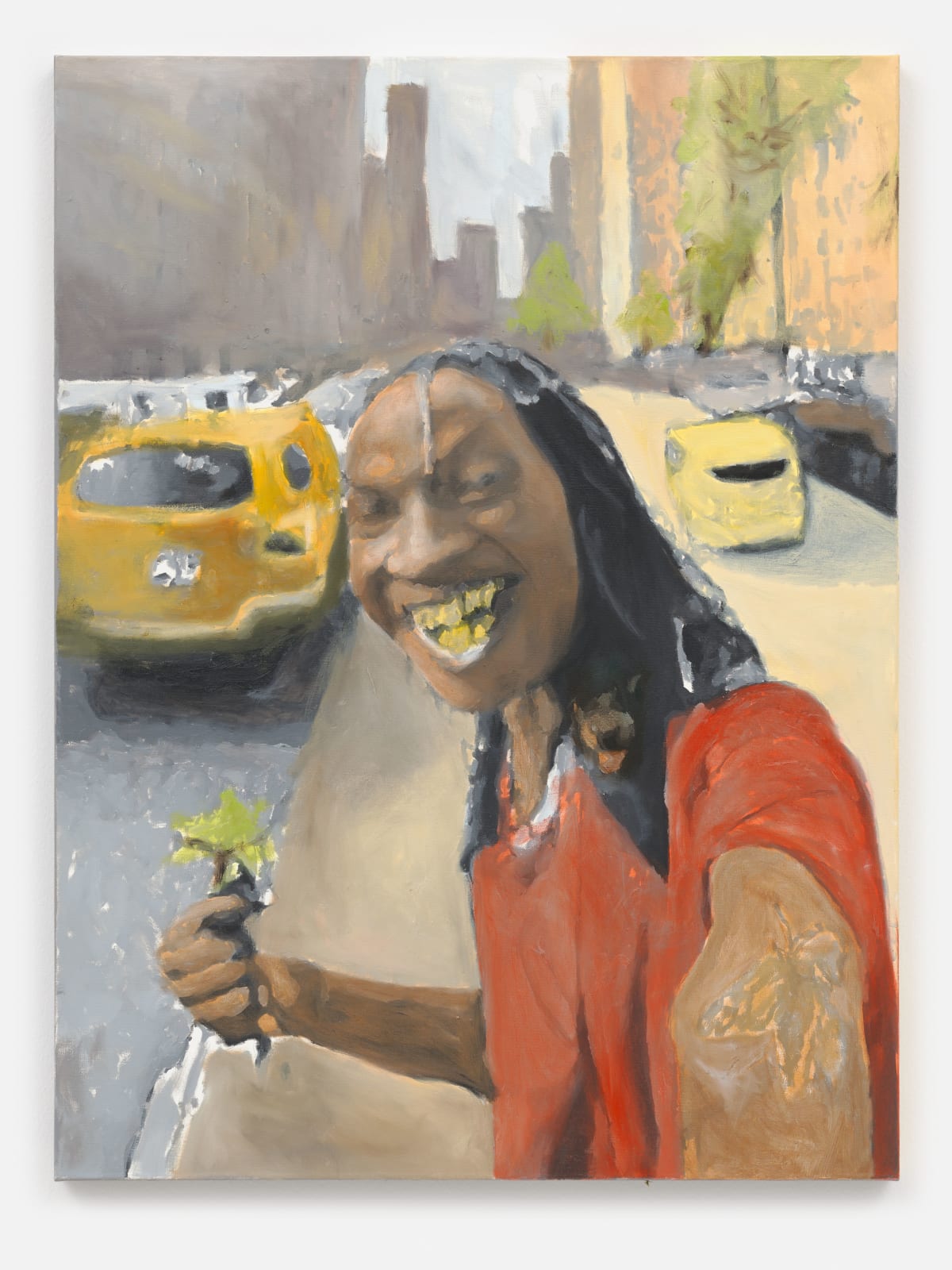

Time Out Clone is an unstable figure. The eyes, nose, mouth, shoulders, and asymmetric dyed blonde (or bewigged) hair – all look misplaced, off-centre, and detached from themselves, as if they were originally from a photo-fit image. This character is inscrutable: the moment you think they are feeling something, the opposite emotion rears up and replaces it.With Eyes on You, meanwhile, the inner drama of the sitter’s personality could well be externally expressed by two silhouettes that cover most of her face and obscure its expression. We can see her burning yellow eyes and upright black hair. But the figures interfere with her nose and partly-opened mouth, and thus cannot get a full sense of what she is feeling or even what she looks like due to the presence of two purple cartoon characters that look like they are preparing to fight each other – what could be something like a ghoulish skeleton on the left-leaning back while also stepping forward, and perhaps a hulking rock goblin, or some iteration of the Michelin Man, ready to grapple. With Tyra in the Middle, however, it may even be the case that the viewer will know precisely who this is. Cruz painted this portrait in oil on wood based on a photograph she took of Banks. Though we don’t know exactly under what circumstances Cruz took the picture, we see Banks in an outfit we can’t really see properly: a shroud like the Grim Reaper, a chador like a religious devotee, a zipless hoodie like someone on their way back from a yoga session. Banks grimaces, almost leering, her shoulders forward as if her arms (which we cannot see), reaching toward the camera to take a selfie or defend herself from the real or imagined paparazzi. This is, of course, a typical angle and gesture for selfie-making, in which we are all not only our own top models but our own paparazzi, too. The gurning figure in Look’ere I picked this up on 125th, and the two sullen skaters in Ice Princesses of Harlem are both products of the occasionally brutalising streets of New York City. Screech, meanwhile, takes place in a similarly threatening place: a graveyard full of tombstones and crucifixes surrounded by gnarled and bitter tree branches, as three figures – more sinister, elfish versions of the three murderous go-go dancers in Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965) – leap and holler, barefoot and dressed in very little indeed, beneath a savage, sickly moon. All three paintings share a kind of facial expression that is not found in Time out Clone or Eyes on You and may be the cause of those paintings’ moody introspection: the vicious gaze of the tormentor. And while Look’ere, Ice Princesses of Harlem, and especially Screech, may, in fact, represent scenes of female solidarity in which these characters have internalised the cruelty of the world as a form of resistance to it, there’s still no escaping the nastiness.

Words by Max L. Feldman