There is a poem by the controversial Italian poet Giuseppe Ungaretti, Eterno, that ruminates on the meaning of a flower. “Tra un fiore colto e l’ altro donato/ l’ inesprimibile nulla.” (“Between a flower plucked and another proffered/ the ineffable nothingness.”) Once offered as a gift, a flower becomes part of the human world, a symbol of love, gratitude, beauty—even sorrow. Nature becomes culture; a real flower is transformed—in this case, by the timelessness of a poem—into an immortal image.

There is a sprig of the most delicate flowers pinned to the wall at Copperfield in London. For anyone familiar with the flora of the Mediterranean Basin, the plant, Dittrichia Viscosa (known as sticky fleabane or false yellowhead), is very recognisable. The flowering weed is unusually tenacious and, as Littwitz discovered in her research, it has a psychotoxic effect on several other species, inhibiting their growth. The plant is known in botanical terms as “pioneer”, as it has successfully colonised many different habitats—yet it is considered a weed, and therefore invasive.

The title of the work, by Ella Littwitz is The Act of Growing Up, a play on the word “aliyah”, meaning “going up”—a term used by Jewish people referring to the idea of a Jewish person emigrating to Israel, and by doing so, fulfilling the Zionist ideal. Yet our encounter is with an uprooted plant that has been displaced. No matter how entrenched in the soil its roots may have been, it is only cultural classification that determines their status in the ecosystem.

Littwitz has cast the plant with heart-wrenching precision in bronze. She has transformed it, like Ungaretti in his poem, into an eternal image, with love and intention, but there is an ineffable gap between the real plant and the image we encounter in the gallery.

It is just one of a series of slow-burning visual traps Littwitz unfurls at her first UK exhibition, No Vestige of A Beginning, No Prospect of An End. The Haifa-born artist, who was awarded the Discovery Prize at Art Brussels last week, uses material forms to invite certain instinctive responses, but the works then unravel hidden complexities by contemplation. At first, they might appear to be conceptual but they are very grounded, quite literally in some instances, in specific, carefully researched events.

The artist has spent a lot of time studying botany of her region (in her work Uproot, she reproduces a book on weeds in Palestine), and through these investigations, she has made some surprising revelations that she shares through her work. The most recent work on show at Copperfield, More poetry than instruction, is based on blueprints for forests in pre and post Mandate Israel that Littwitz came across at The Central Zionist Archives. These sketches seem to forget part of the Zionist ideology, to turn the barren desert landscape into something more European, “to make the desert bloom!”. Yet again, following this line of thought further, the trees can be read as both a weapon—the claiming of land by planting—and a target (in the 1980s, acts of arson targeted forests in Israel were frequent). Littwitz never serves a straight critique—she is, it seems, less interested in asserting her own position than in calling on us to challenge our own.

Littwitz continues to draw on the breach between nature and culture: the earthy, muted colours of the five works in the space give an immediate sense of this, but if you explore their background, each has a story about land and territory—almost like parables, but with no neat moral conclusion. Seam ReZone is a rhizomatic floor sculpture, comprised of twenty-eight deconstructed, splayed-out leather footballs, sewn together by hand. They immediately recall some kind of scientific map, but they reference an event in 1965 when Israeli and Jordanian soldiers worked together to retrieve the lost footballs of an Arab school that had landed in a minefield that divided Jerusalem until 1967. It is the most hopeful work in the show, but it does not offer a solution.

This exhibition is about Zionism and it is also, unavoidably, about conflict. It’s firstly a deeply personal, internal conflict—the artist’s own fraught relationship with her homeland, physically and psychically, and her confrontation with its politics as a Jewish Israeli. It’s also a conflict between the individual experience and the public, between the often knee-jerk responses to Israel from both outsiders and those living there. There is also a discussion of a universal conflict inherent in our ideological relationship to the earth, both as a terrain and as a territory.

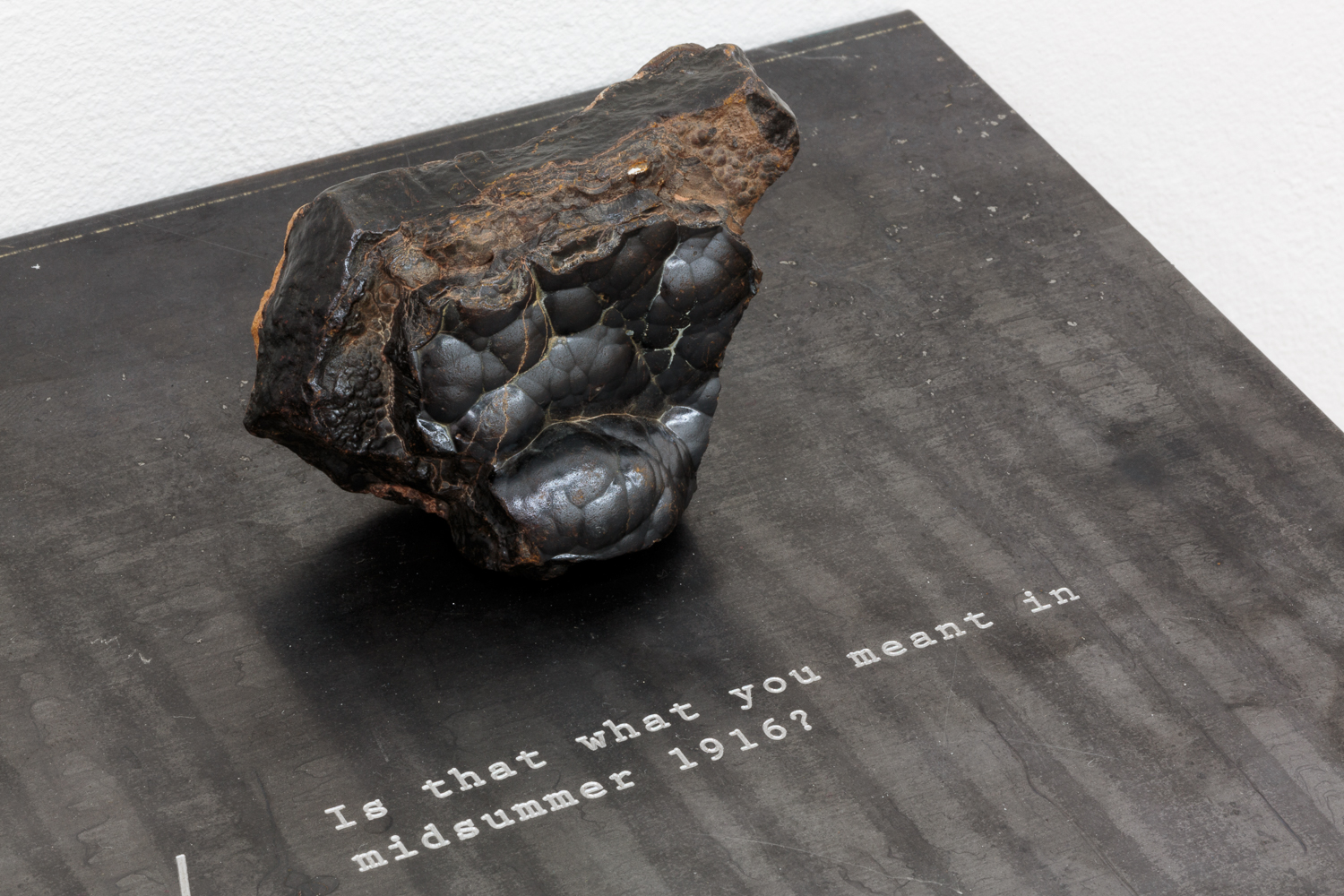

It’s no accident that everything here is fragile: even the chunk of marked rock, Like a shadow of a great rock in a weary land (its title refers simultaneously to a passage in the Bible, Isaiah 32, and a text by Mark Twain on his visit to the Holy Land in 1869), that prompts reflections on guidance and leadership, between image and reality, ideal and real, teeters precariously on its plinth, unstable in its form. Elsewhere, a piece of paper flutters on an iron ore shelf; a chalk drawing diptych can be erased in a second. It perhaps alludes not only to the fragility of ideas but to the vulnerability of anyone who dares to discuss such subjects in public.

The most direct questions come in Untitled (Concrete) in which the artist responds to a text associated with Ze’ev Jabotinsky one hundred and one years on. As Littwitz points out, the text is problematic in many ways, not least as it, in fact, describes Joseph Trumpeldor’s ideas using Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s words, written down many years, perhaps, after they were spoken in a conversation between the two rival leaders.

Two questions from the present day are engraved on the shelf that holds the reproduced excerpt. “Was this what he meant… ?” The terrible urgency of this question—such a contrast to the other, silent works in the show—and the impossibility of getting an answer from the past weighs as heavily on the heart as the lumps of crude iron ore weigh on their very fine iron shelf. How did we get here? Where should we go? How does the knowledge of history serve our future? We’re pointed in many directions, but we’re left with no obvious path to follow.

At a time when politics has become a slew of brash black-and-white statements, and paradox has become policy for the major world leaders, this is a nuanced, subtle political art, for quiet, intimate contemplation and conversation (it is well worth taking a guided tour or reading the provided texts, as the works in themselves are left incomplete). I left thinking about the privilege of my own position. As an outsider, a non-Jewish partner of a non-religious Jewish Israeli, I’ve spent a lot of time in Israel with Arab, Jewish, agnostic, religious, and status-less friends, and do not have to take a stance. As in Ungaretti’s poem, each of us possesses a selfish impulse—the desire to take something from the earth—but we also have the ability to transform this instinct into altruism, a gift, by the mysterious force of creation.

‘Ella Littwitz: No Vestige of a Beginning, No Prospect of an End’ runs until 29 April at Copperfield, London. Installation views courtesy the artist and Copperfield, London.

‘Ella Littwitz: No Vestige of a Beginning, No Prospect of an End’ runs until 29 April at Copperfield, London. Installation views courtesy the artist and Copperfield, London.