“There are so many photographs that exist in the world, why not recycle them?” asks Idris Khan as we wander around his new exhibition at Manchester’s The Whitworth. It’s an attitude which has led him to a very distinctive style of repetition, photographic layering and black-and-white spirituality. With this show being less an ‘exhibition’ but more a collection of his works from the past 5 years, it is exemplified here. Indeed, it’s a style with which the award-winning Northern gallery continues its love affair, having shown his well-known Devil’s Wall in 2011.

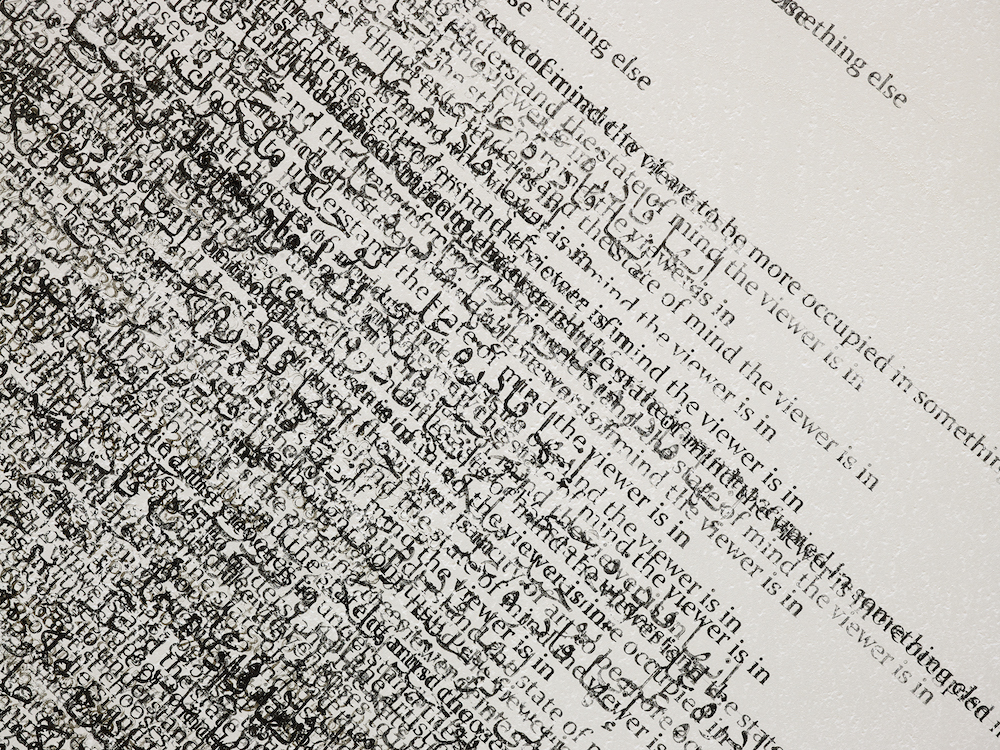

Khan’s underlying ideas of “repetition, surface and spirituality” largely manifest in layering words and motifs taken from secondary sources – often philosophical works – again and again. The centrepiece of the show, True Belief Belongs To The Realm Of Real Knowledge, does exactly this. It forms a mesmeric monochrome mass of information written in both English and Arabic, taking up a whole wall of the space and convincing the viewer that they are about to fall into the centre of an undulating, gaping black hole. Khan tells me: “I really love doing the wall drawings because they envelop the space, they have no real physical bounds apart from time.” Indeed, the piece is site and time specific, but even after the show has finished and it is painted over, he enjoys the element of omnipresence: “It still exists as the fabric of the building, still there until the building itself gets destroyed.”

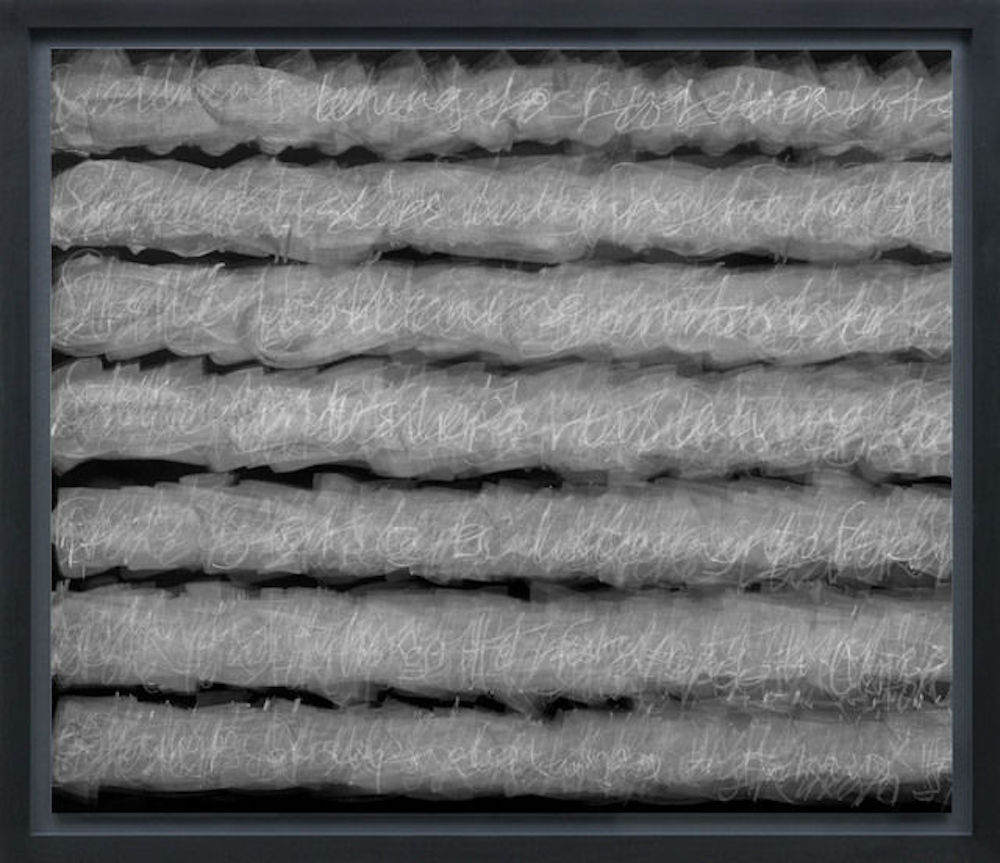

The other works on display draw on secondary materials which encompass the music of Stravinsky, the philosophy of Nietzsche and the paintings of Malevich. The one central strand is Khan’s fascination with surface, and the visual effect of the patterns which he draws from the source material. He takes me across to The Rite Of Spring, which was created by layering every page of the musical score from Stravinsky’s famously controversial ballet. “You think about the musical work and you’ve got a condensation of all those pages of a score, and when you come from afar maybe you don’t even know what it is, maybe it looks like a textile, like it has certain depth. And then as you approach it you start to become aware that it’s sheet music.”

I pose the question of whether these forays into western philosophy and 20th-century classical music mark something of a departure, as a lot of Khan’s previous artwork has been based around Islam and the Quran, reflecting his Muslim upbringing. “The Stravinsky came about because it was a very direct link, it was actually a commission by an architect who was making something with Coco Chanel, who had a relationship with Igor Stravinsky. They met at The Rite Of Spring the first time it was performed, so a controversial first date!

“But I suppose it’s similar to my upbringing and later life. I grew up just outside of Birmingham, in Walsall, and culturally there was not much going on as a kid. Then I was eventually in London surrounded by some of the best artists you could possibly meet at the Royal College, and suddenly I felt like: ‘Fuck, I need to learn a hell of a lot in a short space of time.’ Philosophy was coming at me, music that I’d never really heard before. I always see myself as someone who’s trying to gain knowledge and put it into the work that I make. Why make a work about Nietzsche? The book itself talks about repetition so it makes sense that you would take that philosophy and do this.”

It seems that Khan’s work is sprung far more from his own background, experiences and readings than a photographic tradition. As he says, “it’s always been a painterly tradition for me, though I can’t really claim to be a painter… Frank Stella or Robert Rauschenberg’s paintings are massive for me.” Wherever they come from mentally, these visual distributions of language, knowledge and mysticism form a distinctive and hypnotic aesthetic, one which plays with the viewer’s sense of distance, surface and time. People will be straining to view each piece from all conceivable angles for the duration of the exhibition until March next year, and for good reason.

Idris Khan runs at The Whitworth until 19 March 2017