Like any partner, I used to take photos of my ex-girlfriend all the time. When she would protest, I couldn’t believe that she was unable to see how beautiful she was, that she couldn’t see herself through my eyes—how the beauty poured out of her, in her unspooling gaze, as she pitched it on me. I have a series from a holiday in Dublin that I still regularly seek out, as a reminder of the silken vulnerability and intimacy of our partnership.

For me, this was the natural high from having achieved a level of normativity where my girlfriend and I were just the type of lesbians who went on weekend-long city breaks; there was a certain eroticism in the administrative exploits of folding our passports together in a travel folder or in sharing a holiday budget. We were a proper couple, arriving early for prosecco in the airport, smelling scents in duty-free.

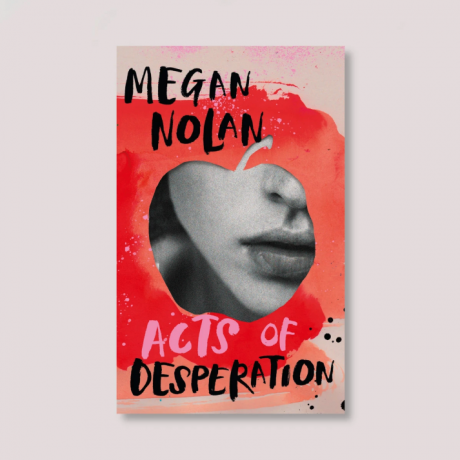

We were fixed in the present but I knew we were building a future, or as Megan Nolan writes in her debut novel Acts of Desperation: “There is infrastructure to be dealt with, dams and bridges and town halls to be planned… Couples will often disappear together for months in their beginning stages which is not just about lust but also about building.” Later, the unnamed narrator, a young woman in her early twenties living in Dublin, describes that when you fall in love with someone “your life is remade”.

“Acts of Desperation sketches all the ways obsessive love and desire is painful, devastating and hopeful”

Like the narrator, I have made and remade my life with various girlfriends, intricately plotting a shared path for our future. I have shared in the dizzying, near magical, often myopic, stimulation that early love provides, which Nolan renders so absolutely that some pages made me wince for their relatability. Acts of Desperation sketches all the ways obsessive love and desire is painful, devastating and hopeful, shining a precise and unrelenting light on what we commit ourselves to in the pursuit of intimacy.

Such is the obsessive, all-consuming nature of love that the narrator feels when she falls for the cold and emotionally unavailable Ciaran, who still loves his ex-girlfriend and seems to mete out his affections like crumbs of bread. Yet the narrator loves Ciaran singularly, despite her friends’ and families’ quiet protestations, against all the insidious turns of cruelty, emotional abuse and violence. She is a loving puppy, tail-wagging, big eyes beaming, unbreakable, indefensible, in the face of the potential for everlasting love. She wants love and the very idea of it to eat her up, drown her, both delicious and suffocating.

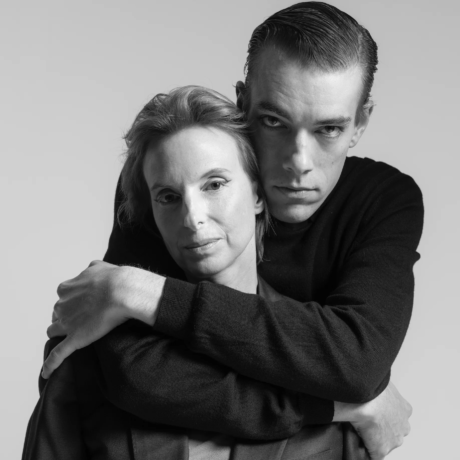

Reading Acts of Desperation, I was reminded of Masahisa Fukase’s From Window (1974), a poignant portrayal of obsessive love. Shot in black-and-white and taken from the height of a bedroom window, From Window is a series of photographs that feature only the photographer’s wife, Yoko. Always taken from above, Fukase hovers above his wife, who leaves for work in the rain with an umbrella, or smiles coyly, or frowns, perhaps annoyed that day that there was another photograph.

How did she feel about 13 years worth of such unyielding analysis? In some, Yoko wears beautiful dresses and pulls silly faces, and yet in others, it is clear why they separated. It was reported in The Guardian that Yoko once described her life with Fukase, as moments of “suffocating dullness interspersed by violent and near suicidal flashes of excitement”. The aerial positioning befits Fukase’s puppeteering obsession, a way to love and control his subject, to hunker down against the inevitable loss of heartbreak, which seems only natural when we know things aren’t right, are conditional and fragile.

“She wants love and the very idea of it to eat her up, drown her, both delicious and suffocating”

Yet, the work is relational, his feelings, his making her laugh, his need for control and the regular routine of photographing her, is refracted through her eyes, her frowns, her smiles, her ecstatic poses. This push and pull between subject and observer is at the heart of Acts of Desperation: the narrator wants to both observe Ciaran like a still and beautiful work of art (they meet in an art gallery) and crawl inside his skin to know and see everything as he feels, to desire other women the way he might desire them.

She constantly bargains with Ciaran through sex, domestic chores and complicated meals of crayfish like neat little gifts. The narrator is often surprised by her canny ability to absorb her own debasement: “I envy women who are removed. I never really had that luxury.” That the narrator refracts this moment through her own need for affection is processed as deplorable, and is testimony to Nolan’s ability to capture the dark and idiosyncratic corners of female desire, in a way that does more to reveal the ways in which we internalise the pathologisation of the female psyche, and in fact might sometimes, however perverse it might sound, actually like it.

Reflecting on Ciaran’s anger and general malaise with the world (he often sits stoically and maddeningly by the window, smoking and reading), the narrator admits that “there was something invigorating about him venting his grievances to me, something unifying and bonding”. Because she is able to partake in his anger, it becomes a shared intimacy, rather than a warning sign. They perform the role of a couple in love, and she experiences “a thrill that can only be described as erotic while choosing a vacuum and a bin”.

“The narrator wants to both observe Ciaran like a still and beautiful work of art and crawl inside his skin”

Despite Ciaran’s waning and conditional love, the narrator is “happy—I smiled, I sang!—when I scrubbed the toilet on my knees”. All these tasks feel “sexy and intimate and even profound”. In doing so, the narrator doesn’t feel begrudging towards Ciaran, she doesn’t feel degraded or humiliated, and she continues to stalk Freja, his ex-girlfriend’s social media, as she subs his rent, cooks his food, cleans his clothes, because she is taking something too, “his ability to live without me easily”.

If Sigmund Freud thought of humiliation as a castration, as that which is a form of depletion, then the narrator of Acts of Desperation is, at first, made whole by the desperation and humiliation she undergoes. It is that which makes her smile and sing, it is that which is waiting for her when she returns home from her shitty admin job.

As the narrator stands making yet another dinner, she reasons that she ‘begged to be standing there over that sink, had begged for that very potato, slimy in my grasping hand’. So what happens when we want the things that cause us to feel humiliation and pleasure at the same time? Wayne Koestenbaum wrote “but are there not certain circumstances where humiliation is not just a horror, but is a route, a passageway, toward something else, something tranquilizing?”

This is true of the narrator’s relationship with Ciaran and their domestic life together: “I had suffered, and I had made the suffering into something I could consider good. I made it so that suffering was a kind of work.” The labour of humiliation is undertaken knowingly and willingly, it is a balm, in a way that is both perfunctory and enjoyed.

It feels incendiary to suggest that we might take pleasure in our own debasement, especially when we are surrounded by corporatised ideals of feminist empowerment, but Acts of Desperation is an experiment in the perverse pleasure, agency and anger we might find in participating in our own abjection.

Come As Softly is a book column by Bryony White on intimacy, desire and sex.