Vilnius-based artist Anastasia Sosunova’s practice moves across media to conjure contemporary folklore, merging Lithuanian mysticism with gated community gossip, scavenging salvaged rubble and subverting Slavic wedding bread. This vision is complete with monsters, ritual and magical thinking, ranging from the sudden enclave of a new-build high-rise, to the psychic draw of a temporary tattoo caked in dirt.

Her work sutures together unlikely companions, bridging the occult with the mainstream, religion with secularity. Folkloric rituals meet the accelerated capitalism of a post-Soviet, Westward-gazing Lithuania to explore its embodied tensions.

Sosunova’s recent solo exhibition at Swallow, a project space located in a creative hub development in Vilnius’s old town, embodies the building’s contradictory interstitial state: piles of rubble and burnt-out Covid-era taxi screens meld with sculptural bread swimming in resin. Meanwhile, Sosunova’s contribution to the current Baltic Triennial 14 sees a traditional Lithuanian wood carving framing her video Agents (2020), in which faceless characters discuss identity, folklore, and the division of post-pandemic public space.

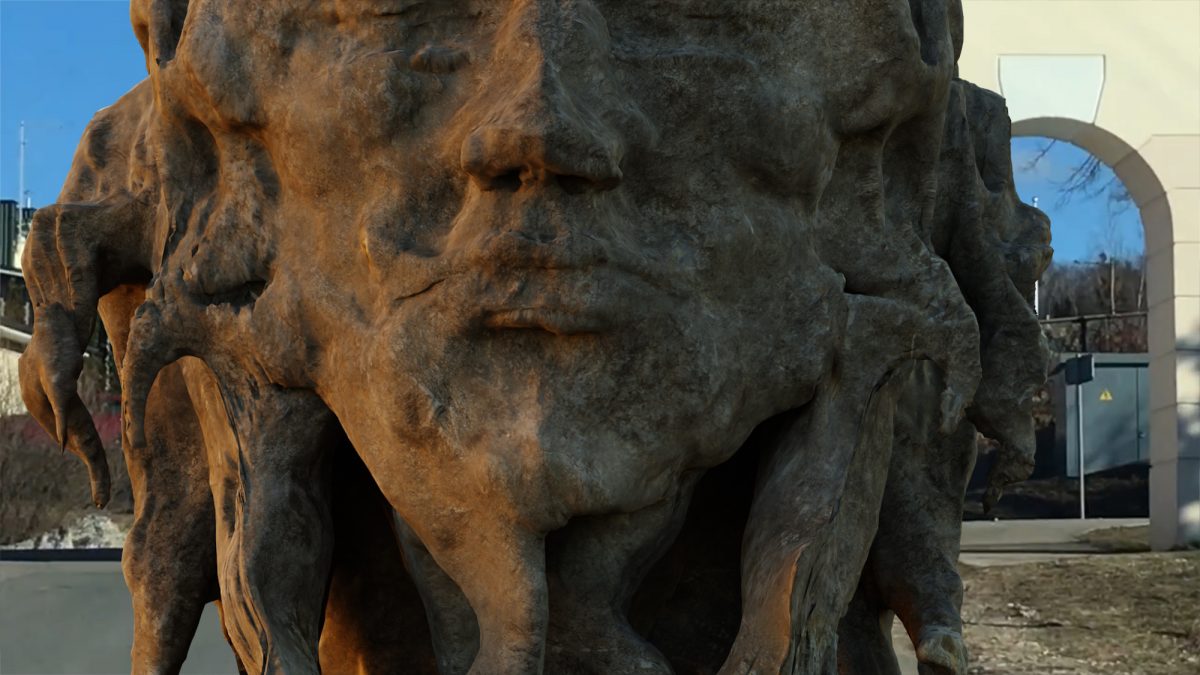

Monsters are key protagonists in Sosunova’s work, appearing as roughly-hewn 3D renderings in her videos and hyper-detailed beasts in her acid-wash engravings. These creatures embody Sosunova’s double-bind of folkloric fiction and sociological critique, a form of metamorphic storytelling that’s always reinventing itself.

Photographer: Laurynas Skeisgiela

Across your work there is an interest in what you’ve termed ‘contemporary folklore’. Can you share a bit about this and how it shapes your practice?

Generally speaking, it teaches me that anything can be made-up and everything can become a story, a speaking symbol or a coping ritual. The word ‘contemporary’ here plays an important role to me, because contemporary means that it is not so much about the past traditions, but about the reinvention of those. They’re still in the making, like a play that is observed in real-time. So if we use this metaphor of sociological study (although it’s not: I don’t have that education), then the whole surrounding world becomes a field where the live-action role-play is happening.

“Anything can be made-up and everything can become a story, a speaking symbol or a coping ritual”

Simultaneously, it’s also about the new stories and hopes that we stitch with the old, expired or politically instrumentalised mythologies, and about looking closely at what kind of politics this stitching gives to us. In practice, this means quite a lot of random filming and taking pictures with my phone, eavesdropping, enjoying encounters, trends and gossip, collecting examples of vernacular art and reproducing it in my work.

Your work, Barry Walking Himself (2019), is set in your new-build apartment complex, a 21st century urban fortress. One of the residents lets their dog Barry roam the shared garden, causing uproar in the neighbourhood…

The new-build apartment complex that you’re talking about is a good example of how the Lithuanian real estate market shapes and segregates the city into the islands of people of similar class and lifestyle, a post-political city. Erik Swyngedouw describes an urbanisation process wherein political questions are subsumed by economic growth. It’s like the cosmic force that you’re just supposed to live with. Barry’s story comes from a middle class young family neighbourhood of uniform architecture where a lot of people are invested in producing the locality of the “village” through various gestures of commonality. These vary from microgestures of care and attention to rather territorial acts of spatial purification, like surveillance. Needless to say: very strict dog walking policies.

“It’s about the new stories and hopes that we stitch with the old, expired or politically instrumentalised mythologies”

- When All This Is Over, Let’s Meet Up!, 2021 (video stills). Produced by Videograms @videograms.online and Swallow

And yet, here’s Barry, a friendly, dappled grey dog owned by the “bad neighbours” who let him out walking on his own without any supervision. To give you some context, free-rambling dogs on the street are usually seen as a relic of provincial Lithuania and the past. But this errant canine agent has gradually become famous as a “village dog”, and introduced as “our Barry”, “It’s Barry, and he’s walking himself” and “Barry isn’t homeless, Barry is OK”.

I loved this story because Barry was a breach in this neoliberal city order, a slippage which felt like the start of a community. The metaphor of Barry walking himself was full of hope. However, another topic that interests me is the problematic topic of gated communities that have been built around the country since the 2000s and are currently experiencing a renaissance. The secular myths prevailing in these neighbourhoods include the idea of the law-abiding good citizen and how nationalistic ideologies are involved in a love affair with capitalism. This is a “bootstrap” theory trope and a general belief in rituals that are supposed to bring people closer to the “Western” ideas and magically defy the Soviet, the underdeveloped, the provincial. It seems to me these myths are protected so religiously that I’m not even sure if they’re secular anymore.

It’s reminiscent of another semi-secular figure that appears in your work: the monster. You write in Express Method that the word ‘monster’ stems from the Latin ‘ monstrare’, meaning to reveal or show, and argue that monsters can reveal the brighter side of the world. How might monsters make this happen, reaching a time where they “represent our desires instead of our fears’?

When I think of this phrase now, I question myself: aren’t our desires somewhat related to our fears? For example, urban anthropologist Jekaterina Lavrinec told me that she often fantasises about Godzilla as a monster that visits a modern city and starts destroying it. “It surfaces from a particular dead-end that civilisation finds itself in when it develops too much and proceeds to be unpleasant to itself”, she says, “This story of a monster defeating an aggressive and monotonous city provides some kind of solace, even hope, or relief.”

“Inventing and engraving various imaginary bodies manifests a possibility for a metamorphosis, the power of shapeshifting”

So there’s a fear that is desired, a destruction which is cathartic. That’s why it’s extremely interesting where imagining and reimagining the monstrous and marvellous takes us: be it the motifs from The Book of Revelation, grotesque costumes of the 17th-century professions, old depictions of “Blemmyae” headless people, or the movie King Kong vs Godzilla. It gives us another assemblage, another image of disassembled and reassembled collective and personal self. To me, inventing and engraving various imaginary bodies manifests a possibility for a metamorphosis, the power of shapeshifting. It’s my self-therapy, a force of liberation from ghosts, shadows and submerged fears.

“I like thinking about most of human culture this way, detecting prayer-charged sites, objects and rituals of the mundane”

In Agents (2020), and the video When all this is over, let’s meet up (2021), you explore the construction of hesitant communities, weighty traditions buoyed up by pop flotsam: temp tatts, Beyoncé bangers, vinyl supermarket ads. How do you navigate the space between ritual and the everyday? Is this collective fetish of the past critically reshaped by present tastes, feelings and atmospheres?

When talking about navigating the space between ritual and the everyday, the Russian word “namolennost’ (prayer-charged) comes to mind. It refers to a quality of objects and sites that arises from the prayers of believers. Far from an Orthodox belief, namolenost is a quality attributed by the community of believers themselves to express a particular prayer-charged energy, grace and authority. I like thinking about most of human culture this way, detecting prayer-charged sites, objects and rituals of the mundane.

I’d like to believe that I don’t feed the fetish you’re talking about, I hope that I don’t give it more power. Rather, I want to unveil how and why it was charged.

Baltic Triennial 14: The Endless Frontier

Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius, 4 June to 5 September 2021

VISIT WEBSITE