I recently read about an office that had forbidden all jokes. Totally forbidden them. No laughing, no horseplay, no communication beyond what is required for everyone to do their individual jobs. There was a surprising amount of support for it from readers in the comments.

One way to make sense of this is as an extreme version of a more general tendency. In mainstream news columns on the future of work, a simple line is drawn between the job itself and the constellation of practices and tasks which are not, really, part of the job.

This attempt to neatly cleave out what is ‘essential’ for the job is an understandable reaction to an expansion of the compulsory non-compulsory activities that work demands. For example: checking emails after hours, bringing the right amount of ‘yourself’ to the workplace, socialising with colleagues after office hours.

To achieve this surgical detachment, workers are encouraged to look inwards, be their own therapist and ask, as individuals, for concessions from their managers, who are in turn encouraged to be understanding. If backed up by the collective power of office workers organised in unions and sealed in bargaining agreements, this approach might have some chance of succeeding. But even if such an approach paid any heed to the dynamics of power, something is missing.

Intra-office sociability is an uneasy zone of freely-made unfree choices. The sociability demanded at work, especially in workplaces where an object of work is relationships between colleagues, is at once coerced and at the same time can exceed the limits of what is demanded by and useful to the firm.

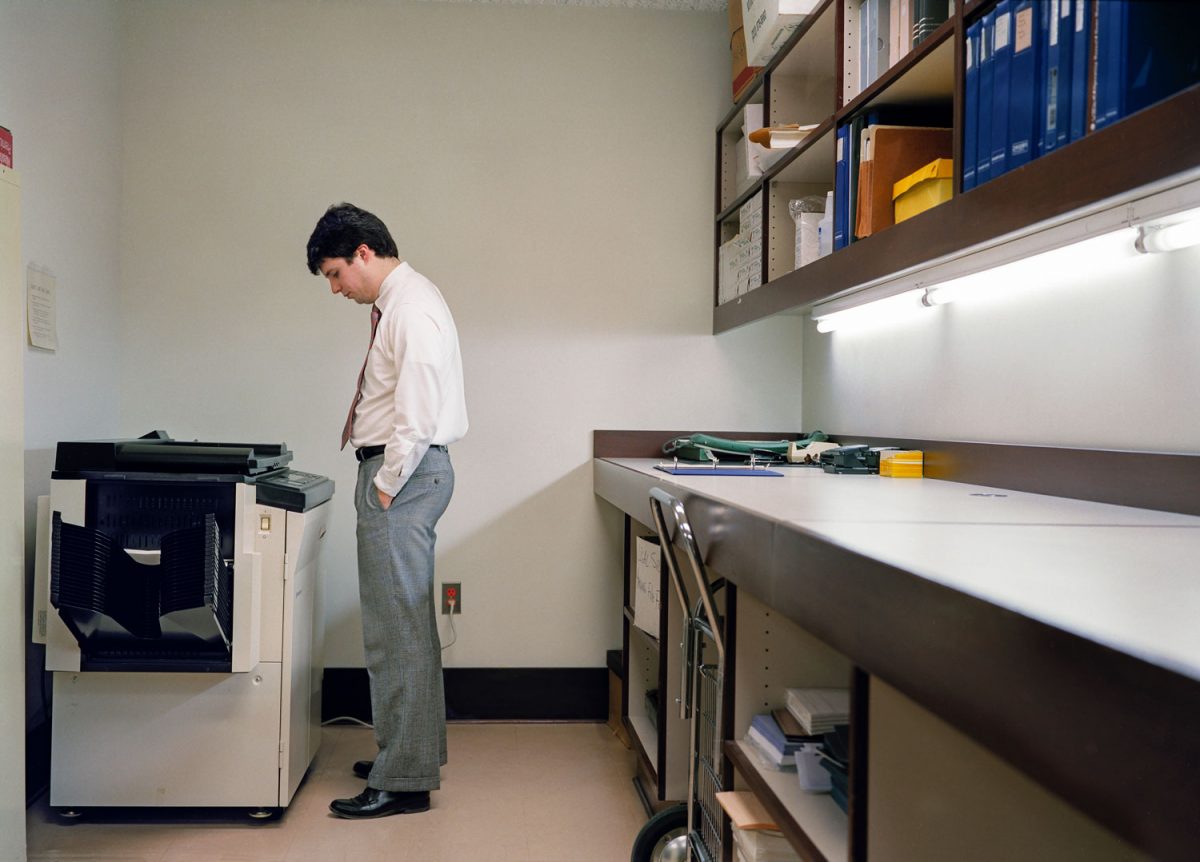

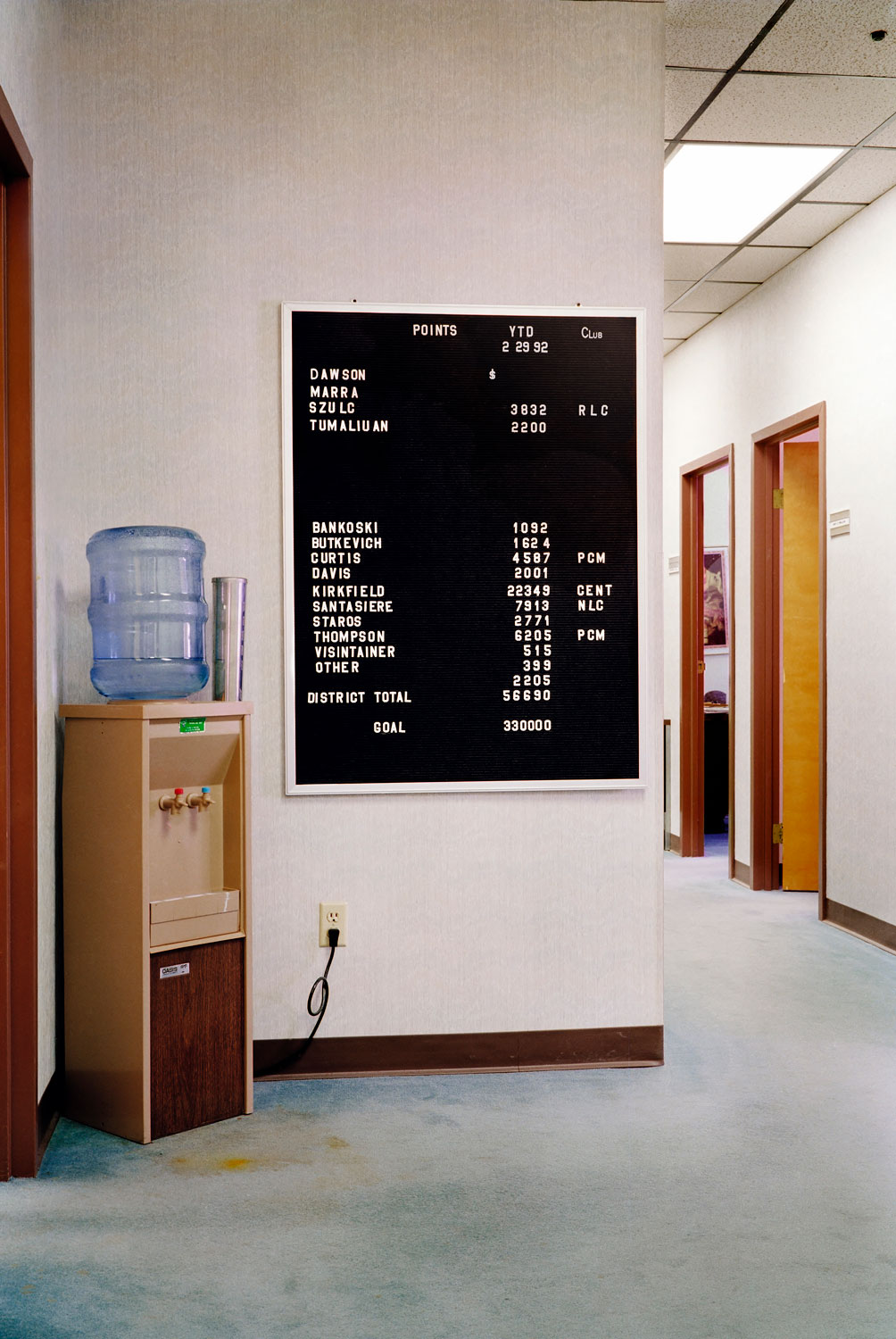

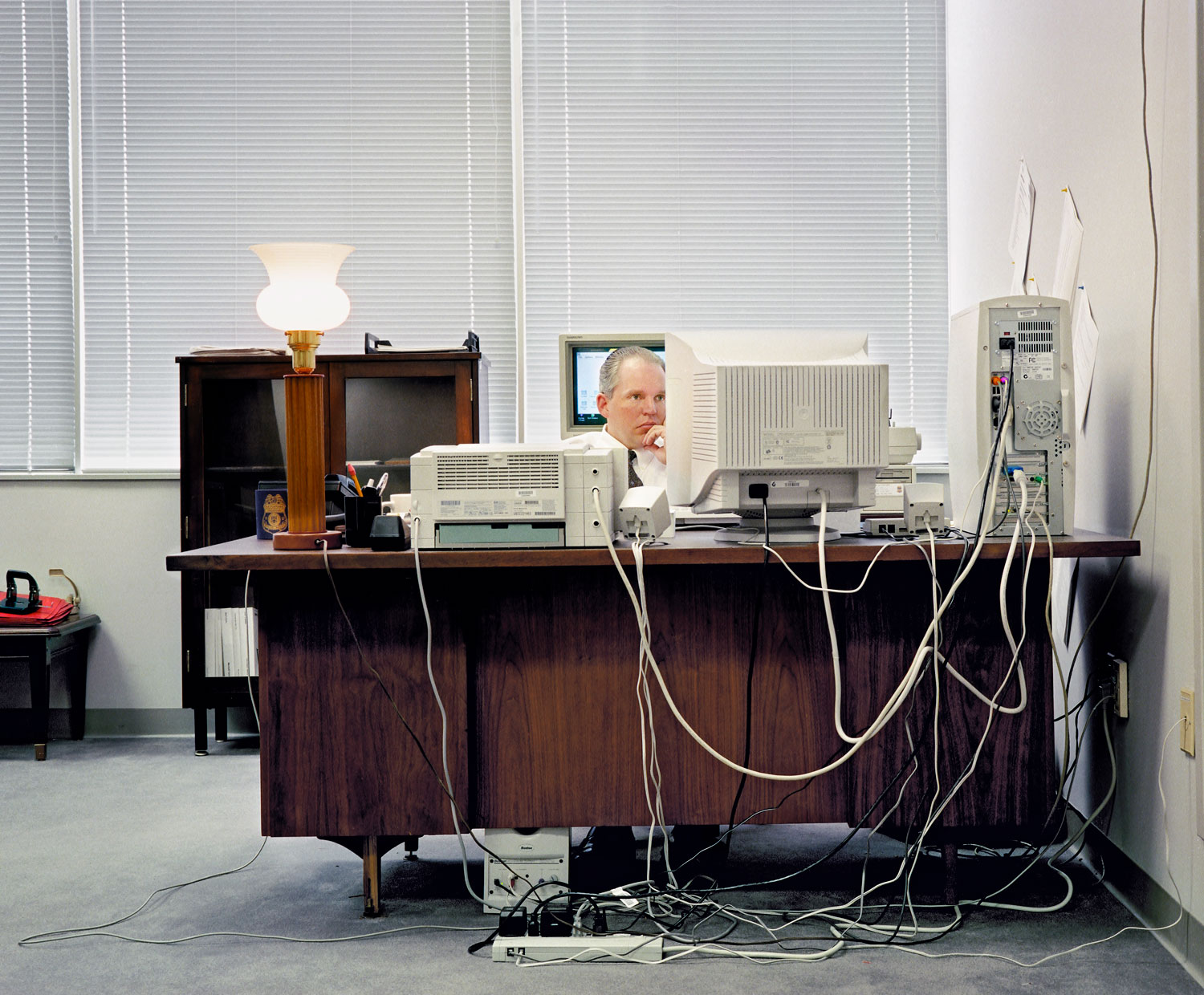

Steven Ahlgren’s The Office, a collection of photos taken in Minneapolis offices between 1990 and 2001 (the kind Ahlgren had himself once worked in) are immediately identifiable as offices, even if their jungles of cables, missing or massive computers, and cubicles, locate them in an era before our own. Although office workers and office work varies across role, pay, status and autonomy, there is an alternately horrifying and soothing sameness to offices.

“Every work landscape has hidden within it a history of struggle”

Many of the photos sit somewhere between portraits and landscapes; there is no obvious focal point and your attention moves from subjects to objects and back again. It moves from the birthday balloons festooning a desk to the downcast face of the office worker whose pale yellow shirt perfectly matches the balloons; then to the pens and paper; the Rolodex; his work materials. This multifocality forces the viewer into the scene, impressing the weight of boredom, its long corridors, its meetings and its cubicles stretching on for the eternity of a working day and a working life. You can practically smell the photocopy toner.

You talk to your colleagues because otherwise writing the same mindless documents that nobody will ever read would be unbearable. You talk to your colleagues because in each interaction there is a kernel of potential resistance. You can sense their frustration with managers, bosses, the whole edifice of capitalist work. They can sense yours, and together, you know what information to keep to yourselves and how to steer clear of those who do not follow this tacit solidarity.

Offices can be fun. There can be a collective giddiness. There are also rivalries, quiet devastations with projects or promotions, crushes, (real or imagined: the most common way to meet a romantic partner is at work), strategising (against the hierarchy or against each other), and all this taking place against the background fact, sometimes acknowledged, that this way of life is not living at all.

Most intriguing of Ahlgren’s photographs are those which show some interaction between office workers. In one, taken in a law firm, we see the back of one office worker, in his hands a piece of typed paper. Another, seated at a desk, looks expectantly. What is the relationship between these two men?

In changing from an office worker to photographer, Ahlgren became fixated on Edward Hopper’s Office at Night (1940) which depicts similar ambiguity and ambivalence. The subjects are colleagues, we know nothing else about them. In another of Ahlgren’s images, a raised finger by one member of a meeting seems to attract scepticism from another. Are there years of resentments simmering under the surface?

“You talk to your colleagues because in each interaction there is a kernel of potential resistance”

Ahlgren shows offices—their rituals and their contradictory sociability—from below, or at least within. The histories of offices are typically told from above. Even the angles from which photos of the office are taken tend to be above and at distance, with rows of desks and, later, of cubicles sprawling infinitely. But every work landscape has hidden within it a history of struggle. Even the modern desk was introduced in the early twentieth century as a technology of Taylorist control—with drawers and details to hide behind removed.

What about the futures of offices? For better or for worse, they seem to have survived the pandemic. In mid-February, office occupancy levels hit 27.5%, their highest since March 2020. This might seem low, but as the Financial Times notes, normal, pre-pandemic occupancy is only 60%.

“Intra-office sociability is an uneasy zone of freely-made unfree choices”

A significant minority of home workers think that working from home is worse for their health and wellbeing (29% compared to 45%)

, and 58% of women homeworkers during the pandemic report feeling more isolated. Rather than home working replacing the office completely, a hybrid model seems likely: three days in the office, two from home. The reports of the office’s death are greatly exaggerated.

The Faustian pact of boredom exchanged for reliable, formal employment guaranteed for decades was already a myth by the time Ahlgren shot Minnesotan offices and their denizens. But today’s workers face heightened precarity. The cost of increased flexibility on the location of work may well be increased surveillance, directly into workers’ homes. The only way to seriously resist this is for the sociability of the office to be transformed, turned against the workplace and towards building workers’ collective power.

But the inchoate class consciousness of professionals, of many office workers, is fragile and ambiguous. For the best part of a century, debates about which way white-collar workers would go, with the bosses or with the workers, have rumbled on.

Even the phrase ‘white collar’ (first used by American writer and political activist Upton Sinclair), was pejorative, intended as a jibe at the self-imposed limits of white-collar consciousness. The business world’s “petty underlings” he writes, “because they are allowed to wear a white collar and to work in the office with the boss, regard themselves as members of the capitalist class.”

The future of the office and office work will, then, hang upon the self-regard of office workers.

Amelia Horgan is a writer from London. Her first book, Lost in Work, is out now from Pluto Press